McKenzie Wark’s new book The Spectacle of Disintegration: Situationist Passages Out of the Twenty-First Century (Verso, out today in the US and May 20 in the UK) completes his non-trilogy of writings on the SI, begun with 50 Years of Recuperation of the Situationist International (Princeton Architectural Press, 2008) and continued with The Beach Beneath the Street (Verso, 2011). I sat down with Wark to discuss the application and recuperation of SI tactics in the contemporary mediated landscape.

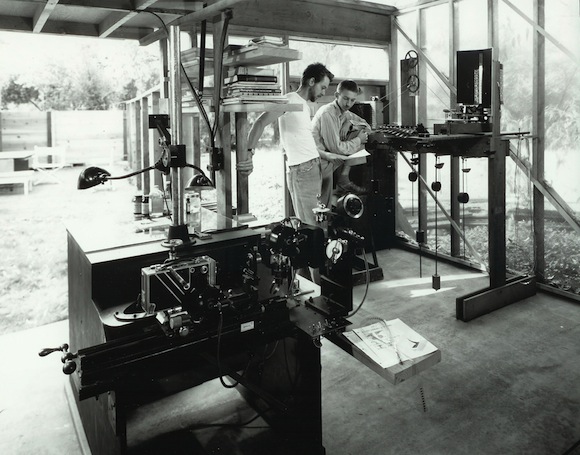

![]() 3D-printed Guy Debord action figures (2012). Produced by McKenzie Wark, design by Peer Hansen, with technical assistance by Rachel L.

3D-printed Guy Debord action figures (2012). Produced by McKenzie Wark, design by Peer Hansen, with technical assistance by Rachel L.

BB: You’re very upfront about how you didn’t intend to write a “great man” history of the Situationist International, instead incorporating marginalized and forgotten figures. Yet The Spectacle of Disintegration focuses on Guy Debord, especially in its second half, if simply because there is no one left.

MW: The place were I started the whole thing was just an obsession with two late texts of Debord’s, Panegyric and In girum imus nocte et consumimur igni. I think they’re two of the most luminous critical Marxist texts, avant-garde texts, prose poems, of the late 20th Century. It took me a long time to even understand what they were doing. And so the whole thing grew over 20 years, just returning to those texts and trying to figure out a framework for interpreting them. The whole project was somehow leading up to writing about those. I learnt to read French by reading these texts. I just taught myself. And my French is terrible. I make no claims to be a scholar of the language or anything like that whatsoever.

BB: Debord’s conception of the interactivity of the spectacle seems to be a bit limited in terms of where we are today. I believe you refer to his conception of it as “a one-way street.”

MW: One of the premises of The Spectacle of Disintegration is that there’s the myth of the overcoming of the spectacular form in the age of the Internet, but what it does is make it microscopic and distribute it throughout the entire media sphere, so we now have micro-spectacular relations rather than one big macro one. So if you think about the old culture industry, everybody was critical of it, but at least it fucking entertained us! You would have all those flaws that Adorno spoke about, the extorted reconciliation of the ending, the equivalence of exchange values, but at least it was offered to you as something to consume. We’ve moved from the era of the culture industry to what I would call the vulture industry, which is companies like Google. I mean, in terms of culture, they don’t make shit. They just allow you to get to stuff that somebody else made. So now we have to even entertain each other. Go on, make some cat videos! So there’s a sense that on one side there’s the outsourcing of the production of the thing, and on the other what I would call the insourcing of the production of the affect. It becomes everyone’s job, but no one is to expect to get paid for it anymore. It was always a struggle if what you wanted to do was be a creative person, to make any living at all. I don’t know if that got any worse. It was always terrible. But the conditions of its terribleness change with each technical evolution.

BB: So now we have all these writers and artists policing the area of ‘we still get paid to do this’. It’s almost like fetishizing outsourcing. Like, can’t we get back to the 1970s when you could make a fuckin’ record and make some money.

MW: Yeah, well, no one ever really made any money. That was like a tiny handful of people. The myth of that tends to leave out the real life of working musicians and writers. We sort of focus on and fetishize a few people who made good. It is worth asking—so now we’re in favor of the commodification of culture? Is that necessarily a bad thing? In some ways, it’s not necessarily a bad thing to have a day job. There’s part of your mind and life that’s completely separate. The fly in that ointment is that whatever version of capitalism this is requires so much affective labor. You’re supposed to be invested in the company and its products. You see people in coffee shops who have become the brand they’re speaking on behalf of, and you’re like, man that’s sad. The Situationists put this on the agenda. They didn’t necessarily have the answers. For example: the idea of détournement, that the whole of the cultural past is a cultural commons that belongs to all of us from which you can appropriate at will—but to correct in the direction of hope. There’s a plagiarism in the correcting gesture. They were thinking about this stuff already in the fifties, and now it's everywhere. We know all of Debord’s major texts are heavily plagiarized. There’s an anticipating in that of the whole of remix culture, but a critique of it as well. To simply mix shit together is not all that. The advertising industry’s been doing that since the days portrayed in Mad Men. You have to do it in such a way that you reveal that culture is really a commons. That’s the sense in which Debord is speaking to the present, even though the tools he did it with are now antiquated.

BB: Remix bots like @KimKierkegaardashian seem to be accomplishing détournement without conscious human input.

MW: I followed that one for a while; it’s hilarious. I kind of love that stuff because it’s so revealing. The side of culture that’s really a giant automatic repurposing machine. Can you build a bot that would, for example, build sentences? And then flip that into the space where it’s the negative, the critique of that very practice? Can you create protocols using a search engine to generate language? That reveals exactly the great poison sea we’re swimming in.

BB: Which kind of feeds into all these recent copyright scandals, like the ones involving Jonah Lehrer and Quentin Rowan, who didn’t even attempt to use arguments about intellectual property being fair game. Rowan could have come out and just been like, I’m just fucking with you guys.

MW: It’s a shame. The Society of the Spectacle is really brilliant prose. There’s entire chunks of all sorts of things not even entirely digested into it. Like it suddenly starts to read like Hegel translated into French. That’s because that’s exactly what it is! Or the films Debord makes after Gérard Lebovici becomes his sponsor. I tracked down Martine Barraqué, Debord’s film editor. She explained that all the newsreel footage, you could just buy that, but the feature films, they just straight up lied about what they wanted them for. They created all these elaborate stories like, “Oh, I’m the production assistant to a famous American film director who would like to see something. We need it for three days...” Because that’s how long it takes to copy a piece of a feature film, so it could be stuck into The Society of the Spectacle or so on. You just sort of think, wow, it’s just so friggin’ hard and laborious to steal this stuff outright. And Martine talks about how they had to build whole databases of film by category. The Internet just does all this for you now, but they were kind of inventing a practice of making remix, détournement cinema from scratch. But yeah, we still live with the myth of the romantic author, the creator. This idea that, oh I made that with my own labor, so it must be my property. So it’s like yeah, you and whose fucking army made that? Labor’s always social and collective. Including the labor that produces culture. Let’s not forget all the scandals about often very prominent historians in the US writing about really well-worn topics who can’t even tell the difference between their own prose and somebody else’s. And it’s like, oh it’s an accident, I just forgot to put the quote marks around it. Well, you’re just revealing that all of bourgeois thought is identical with itself. You really have no ideas, you’re just moving it around a bit.

BB: If the SI prized concealment almost to the point of fetishization, do their analyses and strategies lose something in a society where concealment has become not only more difficult to achieve but almost undesired?

MW: I write in The Spectacle of Disintegration about Debord’s widow Alice Becker-Ho’s work on "gypsy" or rather Romani language as being the source of underworld cant or slang or jargon. Slang not in the sense of how it turns up in hip-hop, but in terms of ways of both concealing and stating at the same time. It’s a kind of cliché that we live in this culture of over-exposure in which, if you even attempt to secrete part of yourself, you’ll just draw more attention—from companies as well as from law enforcement. But I think there are ways of stating things that are intelligible for "those who are in the know," to use a Becker-Ho phrase. Ways of being public that aren’t quite what they seem. It reminds me of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest. We now know that “earnest” was late 19th-Century slang for homosexual. So that strikes me as kind of useful, that you can occupy a place in the disintegrating spectacle but not quite be what you seem. And that struck me as being kind of the last space available. ‘Cause if you try and do a withdrawal thing like the Tarnac Nine, it will get you arrested. And who really wants to be Žižek? There’s only one at a time, occupying a space in the disintegrating spectacle in a certain way.

BB: This kind of plays into the whole anonymous with a lowercase “a” thing—the whole fight to be able to create an independent identity on the net and, to take it to an extreme, to be a troll and not to be exposed.

MW: What I learned from the comrades in the labor movement back in the day is: always assume you could be under surveillance but not that you are. There’s a certain vanity in assuming you are. So all of your statements need to be able to pass muster. Debord has this lovely riff in, I think it’s in Comments on the Society of the Spectacle where he says, I don’t abjure any of the statements I made to the police, but I don’t want them in my collected works because of scruples about the form. That is brilliant. So those statements would pass muster as literary texts, but they’ve been redacted by a police officer who’s garbled all these sentences. You have to earn even those statements.

BB: Does maker culture, and its mass-market mirror of “artisanal” production, have any shared roots with the SI’s emphasis on producing highly-designed, limited-run free journals and books?

MW: Yes and no. One wouldn’t want to be part of this whole disruptive technology language, which is pure California ideology [Ed. – “The Californian Ideology” was a 1995 essay by Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron exploring the “counter-culture libertarianism” at work in Silicon Valley technoculture]. One would not want to get too close to the petit bourgeois Brooklynization of everything, the organic beard oil for 20 dollars. But, I think, not just Marxists, but a lot of people with pretensions to critical theory got very remote from practices of making, and to not understand the production technologies of our time is an enormous oversight. To at least know how to make one thing is an extremely helpful way of understanding what production is, what labor is. So with the launch of The Spectacle of Disintegration, I’m doing limited edition Guy Debord action figures that are 3D printed, and we’re gonna release the file to print your own for free. There is something that is really interesting about 3D printing, but it’s a proprietary technology. On the one hand, it enables a certain kind of détournement, but on the other hand is already being recuperated before it’s even on the market. I actually walked past MakerBot on my way here. Just down on Houston, there’s a little showroom down there, and it kind of reminds me of the Apple 2 before the Mac. It’s at that stage. So yeah I really recommend that one do what Debord did in that sense. He learned how to produce journals. He was really good at it. He was a good editor and production manager. The twelve issues of the Internationale Situationniste are really lovely handmade objects.

BB: Is the “attention economy” some kind of corruption of the concept of potlatch?

MW: The Letterist International journal, Potlatch, was never to be for sale. It was only given to certain selected people and then some other people randomly selected from the phone book. Apparently, it would turn up for sale in those little book stalls along the river in Paris. And it was very, very low-rent. Michèle Bernstein would rent a typewriter and bang out—she was the woman, so she had to do the physical labor—all the texts on the typewriter and then duplicate it. But it was already posing questions about economies of access and attention. You’re in the post-war period, and there’s a myth of production of images and stories, which there was an intimation of back in the 19th Century, but by the post-war period the deluge kind of begins. They paid attention to the strategies of the advertising industry and were looking for ways to create work that partially subtracts itself into another kind of temporality. It’s a sort of partial invisibility to create a different kind of attention for different people. In the critical theory tradition, this is really quite new. For the Futurists and the Surrealists, it was still early days for a spectacle. The Futurists start by taking out an advertisement on the front page of a newspaper. You could still do that in 1909. But I think there’s a canniness about the fact that the attention-seeking strategies of the older avant-garde would no longer work in the post-war period.

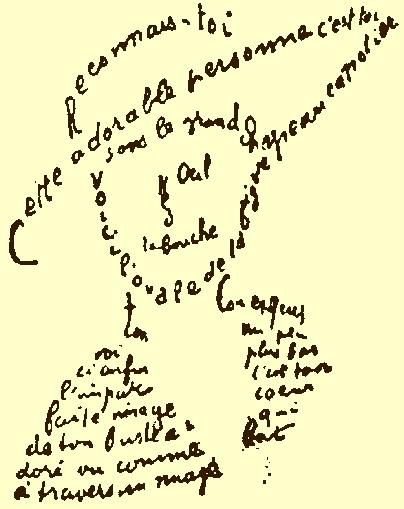

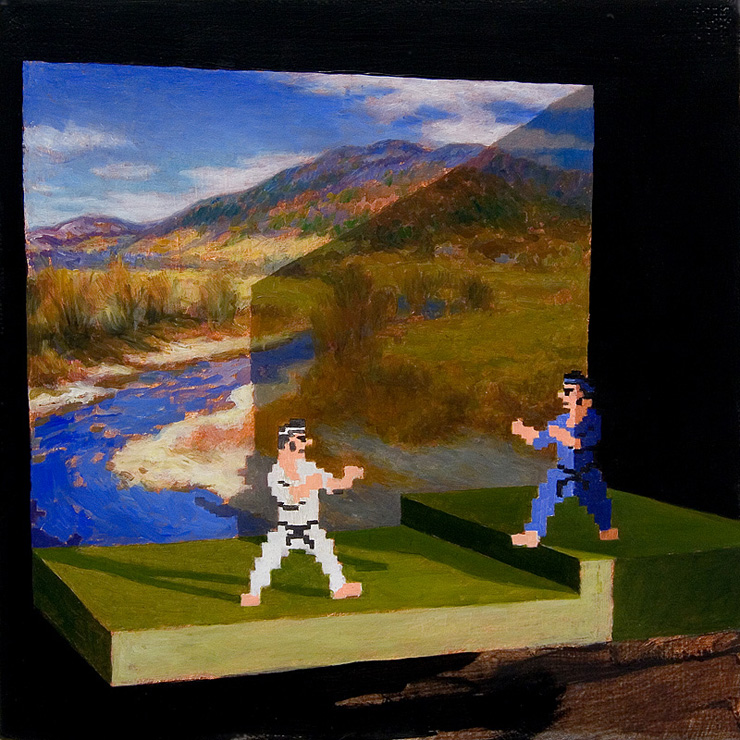

BB: Researchers at Northeastern University in Boston have developed an algorithm which can, with an approximately 93% accuracy, tell based on a person’s mobile-phone records “where that person is at any moment of the day”, according to The Economist. This seems to, in a certain way, back up some of the SI’s theories.

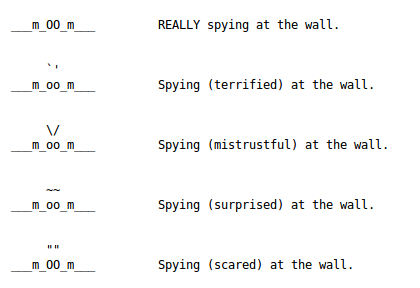

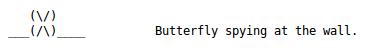

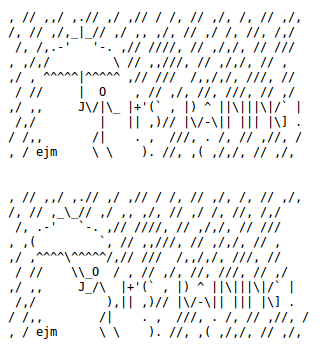

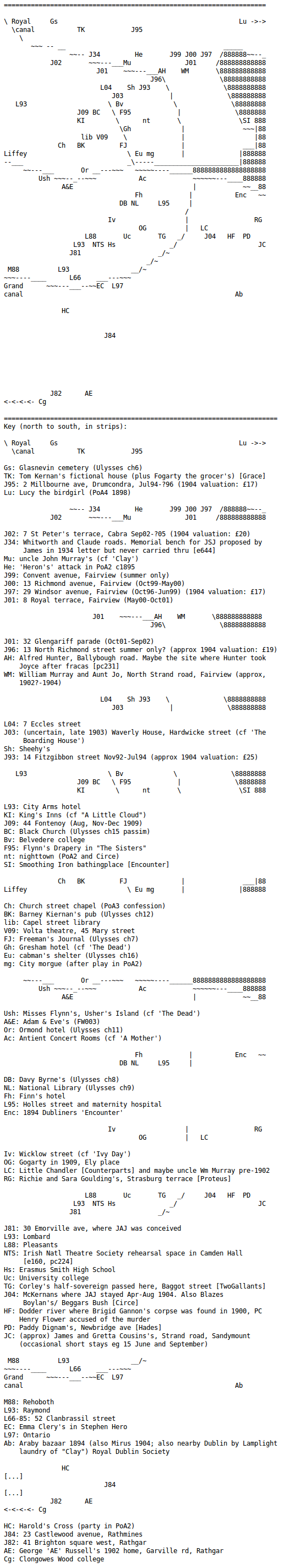

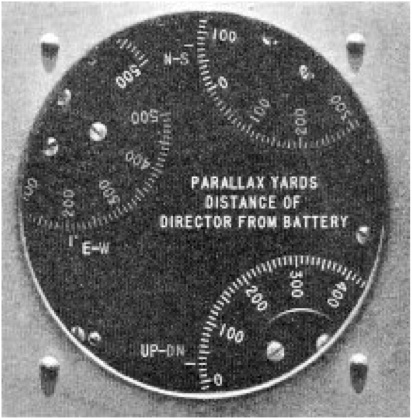

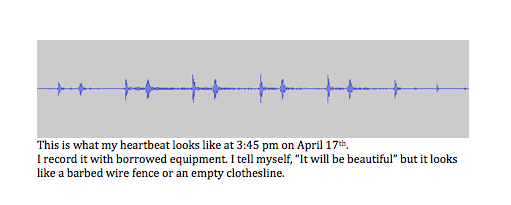

MW: Yeah, Debord is reading Paul-Henry Chombart de Lauwe, who is this great urban sociologist, the first person who was trying to map people’s pathways, and Debord, riffing off Henri Lefebvre’s The Critique of Everyday Life, is gonna start with the predictability of that. Now we’ve reached the point of real-time analysis and application—which runs almost exclusively to selling you stuff. One thing the Situationists were doing was looking for the free space in the Paris of the 1950s, with this massive police presence and surveillance. In the division between work time and leisure time and its routine, there was still a place of play, provided you live by the slogan Never Work. Well, there is no longer any difference between work and play. There’s no such thing as leisure and non-leisure. We’re all working all the friggin’ time. But when we’re working, we’re goofing off half that time anyway. Does anyone even know when they’re working anymore? I’m talking about in what the Situationists called the 'overdeveloped' world. I do all my work in coffee shops, and I see people constantly juggling stuff that’s either work or not work, god only knows what it is. As the grid tightens, it in certain senses becomes more diffuse. So it’s not to deny how geolocation is involved in surveillance or 3D printing is rapidly becoming proprietary, but it’s to figure out what can you produce within the space of those things that suggests another world entirely.

![]()

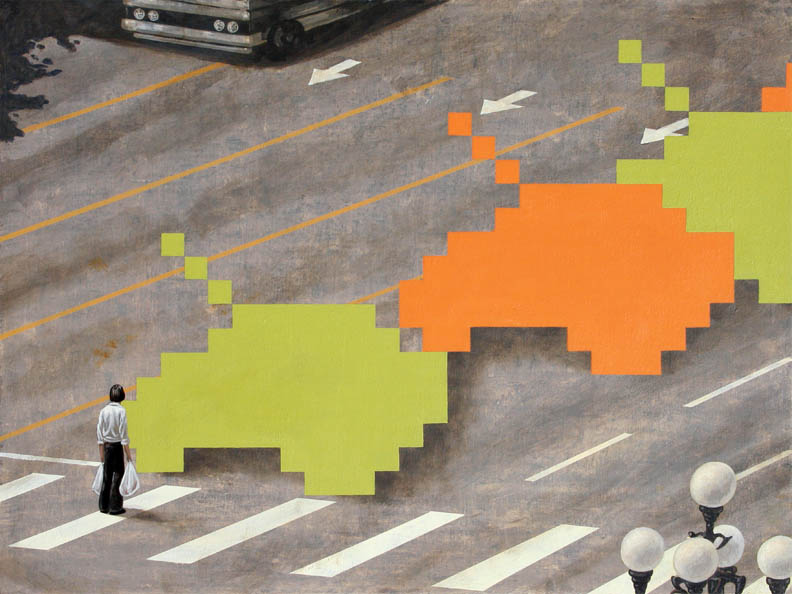

Paul-Henri Chombart de Lauwe, map of a young woman's movements in Paris, 1957

BB: In your first book, Virtual Geography, you define Global Media Events as “singular irruptions into the regular flow of media”, and focus on four, including the Wall Street crash of ‘87 and Tiananmen Square. Do you think that such “singular irruptions” are still possible in our current mediated landscape?

MW: Yeah! In the sense that they were defined in that book as completely unanticipated in the media narratives of the time. And then of course someone comes along and says, “Oh, that crash is just like the last one.” But in the rhetoric of the time it was unthinkable, just as 2008 was unthinkable to all but a tiny handful of folks. So, yes I think there are still interruptions in the narrative space-time, and it’s a question of method. As soon as a weird global media event like that happens, start recording everything, because when the media has no idea what the narrative is, then they experiment with all kinds of weird shit, like interviewing crazy people who would never otherwise be on the air, speculating wantonly and randomly, and that’s the stuff. You capture that, and that gives you a window into that break in the narrative space-time the spectacle can imply. The scariest one I went through personally was 9/11. Truly extraordinary stuff went on the air. You saw people jump out of the fucking building. Live. That stuff’s never been shown on television ever again. The event has been edited down to two or three images. So yeah, I think the method still works. Don’t give me this shit about Twitter revolutions, I was writing about this in the ‘90s! About how things like fax machines play into the space of Tiananmen Square. The first Twitter revolution is 1848, when the telegraph is already beginning to change the space-time in which things happen. We always have the same ridiculous debate about, Ooh it’s the new media, and it’s like, no, events only happen because of the political actors. It’s a total category mistake; there’s no such thing as politics outside of the media. Or vice versa.

BB: In The Spectacle of Disintegration, you specifically state you don’t want to name the inheritors of the SI’s spirit, yet in five years earlier in 50 Years of Recuperation of the Situationist International, you named a small group, including the Bernadette Corporation, DJ Spooky, and the Critical Art Ensemble. I was curious why you revised your stance.

MW: Well, not to slight those folks, but it just struck me in retrospect as a bad idea. Anyone can "inherit" the spirit of the Situationists. One of the sources of this whole project was I was on a Listserv in the ‘90s called Nettime which was kind of like media central for a whole series of avant-garde actions. I thought, I want to write about that, but it was too rhizomatic, so I started by rereading The Society of the Spectacle, something everyone involved probably read, and I said, “Holy fuck, it doesn’t say what I thought it said!” So I got sidetracked into this whole thing. It’s still a project I’d like to do some day. It’s much broader than just one or two groups, and all of them have their locations in a sense, the Bernadette Corporation folds back into the art world, a bit precipitously I suppose. The myth in the art world was that the avant-garde disappeared. No it didn’t, it just had nothing to do with the art world anymore, because when art becomes contemporary art, it’s just another category of commodity production. The avant-garde is now attached to media and design. There’s still a project to kind to recover those stories, extract what’s living and what’s dead, extract the concepts, make it available for folks to do it all over again. Avant-gardes are always extremely historically aware. They just want to deny it and pretend they’re not repeating.

BB: Do you see any of today’s social thinkers who stand in opposition to the gadget age, and here I’m thinking of people like Sherry Turkle and Evgeny Morozov, as coming from an SI background?

MW: No, and the most common mistake is to mistake the current form of a technology for technology at its basic potential. How many times do we have to do the same old stupid bullshit over and over again? It’s all one-sided and undialectical and frankly very uninteresting. So alright you don’t like technology. Technology is the human. We’re the tool-making species. There is no human independent from its tool apparatus. The question is: does it have to be these tools? Absolutely not. So how does one reimagine the potential, the set of the scientific discoveries and their technical applications, and open up so life could be otherwise? That’s the critical task. There’s an absolute failure to perform the critical task in relation to technology. There’s a kind of "No, I don’t like the iPhone." Well, what the fuck do you like then? What do you want? Describe another world. Describe it to me. For seven billion people. Among the Situationists, someone like Constant Nieuwenhuys did exactly that, he imagined an entire other planet based on mid 20th Century technology. That’s more of a conceptual exercise than a real engineering project, but it opens a door to asking question about how, well, how do you reengineer cities? So that they’re survivable would do for a start, but better than. We really could abolish work, y’know? Not completely. But we could really get it down to a few hours a day. So, well, how’s that project going? We’re gonna run out of cheap labor eventually. It can’t go on forever. There’s signs that China has turned a corner. They just don’t wanna do these boring factory jobs. Alright, so we’ll go exploit cheap labor in Vietnam. But it can’t go on forever. So that opens the question of, well, we’re only using this cheap labor ‘cause it’s so cheap, sitting there all day with a screwdriver assembling those cheap plastic toys. Now you look at all those plastic toys with ten screws in them. Well, they’re only designed to have ten screws because it’s cheaper to use the labor than to design the fucking thing properly so it snaps together. So at some point technology has to be part of the critical conversation. And that’s where hackspace culture, hacker culture, some of maker culture, is so incredibly helpful. It’s equipping people with a basic knowledge of how our world actually works. But you have to add the question of how could it work better, how could it work differently. And as a totality, not just "I want a better widget." What would be a better system? That’s the whole critical design question. The central question to me now is the avant garde of design.

BB: There’s a certain strain of tech utopianism, personified now perhaps in the figure of the late Aaron Swartz, who are for using tech to bring about an “open culture.” How at odds with the SI’s interest in concealment is this?

MW: Aaron Swartz’s story is tragic in more ways than one, but you have to ask how politically aware his mentors actually were. Marx says in The Communist Manifesto, who are the forces of social change? Those who ask the property question. And Swartz did. It got him into all sorts of trouble. So I think there’s a kind of reformist dimension to openness, but there’s also an attempt to recuperate the energy of a social movement that has basically decided that all of culture really does belong to all of us. It’s file-sharing. That to me is one of the biggest social movements of the early 21st Century: 'These are my dreams, these are my desires. So I’m taking them back thankyouverymuch.' And then some people, not everyone, go, 'Oh and then I’ll share it with everyone as well, because it all belongs to all of us. We all made this!' So there’s a fundamental rethinking of the relationship between gift and commodity going on there. And it gets recuperated back into industrial structures. The whole of what I call the vectoralist class is attempting to recommodify at a different threshold. Google doesn’t give a rat’s ass who owns whatever it is you’re searching for. It just wants your data and to sell ads at you based on that data. Here’s all this free information, you can have that, but we want you to give up more information than what we’re giving you. If you see it as a political compromise between the fact that information wants to be free but is everywhere in chains, it’s like, Oh we’re just gonna rearrange the chains a little bit. So we need that historical perspective of the shifting of frontiers that respond to the social movement. That’s the crucial bit that’s often missing from popular writing about this stuff.

BB: There’s been kind of a second wave of recuperation of the SI since the mid to late aughts. What do you think the drivers of this wave are?

MW: It’s hard to tell if it’s a pattern or if it’s random. But there were a bunch of attempts in the late ‘80s to tell the story. The famous show was at ICA Boston and the Pompidou Center, which Debord famously refused to attend. And Greil Marcus’ book came out. As the SI said: 'our ideas are on everyone’s mind.' They really understood the boredom of commodity capitalism. While they’re dealing with an earlier phase of it, it’s still true. There’s still something about boredom in the way the commodity responds to desire imperfectly. So maybe it’s just that it still speaks to people. Debord’s widow Alice Becker-Ho just sold the archives to the Bibliothèque nationale for an astonishingly large sum of money, if the rumors are true. She tried to sell it to Yale, I think, knowing that this would provoke the French government into declaring Debord a national treasure, which means that the manuscripts can’t leave the country if the price can be almost matched. There’s a way in which the museum industry and the scholarship industry require rare, special things to base whole careers around. You now have to go the Bibliothèque nationale to see the holograph of Debord’sThe Society of the Spectacle. I saw it in a glass case; I’ve never actually read the manuscript. “Real scholars” have to work in the presence of the sacred aura of the thing. It’s kind of ironic given the nature of the stuff. One of the reasons I like to teach the SI is that all the texts are free in translation on the Internet. It’s everywhere and done by amateurs, but done lovingly. So there is a kind of auto-museological side to avant-gardes themselves. These are the folks who are in this, creating it. Rather than the sense that, now that almost everyone’s safely dead we can add this to a canonic succession and teach it after all. I don’t really care. There’s two competing histories. There’s what I call low theory. This stuff is now part of high theory. I really couldn’t care less. But this other tradition of low theory has already decided that this is stuff it wants to curate and share freely and give away. I’m part of that.