The Museum of Modern Art is making headlines in the wake of its recently opened exhibition, Soundings: A Contemporary Score (recently reviewed for Rhizome by Sam Hart). Organized by Barbara London, associate curator in the department of media and performance, and Leora Morinis, curatorial assistant, the exhibition stands as the museum's first major presentation of sound art.

Soundings thus marks a pivotal moment in the history of sound in the arts, as one of the world's most influential art institutions converges with a longstanding tradition of sound-based artistic practice for the first time. I met with London after seeing the show to discuss the exhibition and her curatorial process. The following is an extract from the full transcript of our conversation.

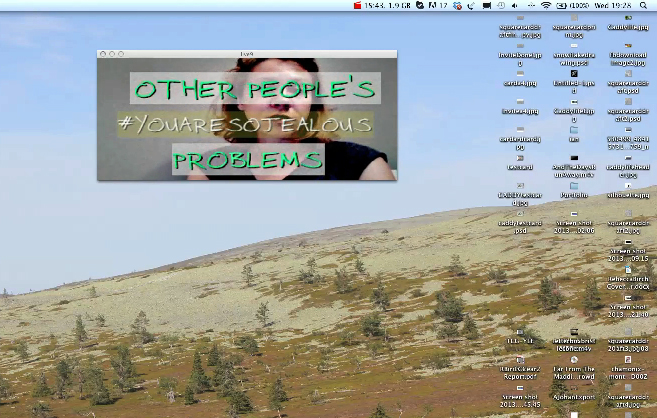

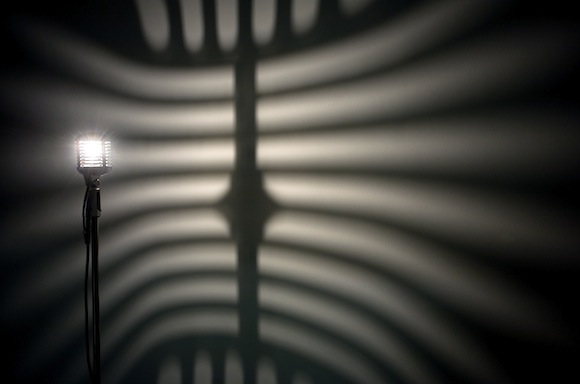

Camille Norment, Triplight (2008). Microphone cage, stand, light, electronics. Courtesy the artist.

CE: How did the Soundings exhibition first come about? The exhibition has opened in 2013, so you must have started planning around 2010?

BL: Something like that. But, you know, I did the series Looking at Music, and was interested in the influence of music on contemporary art practice. That was very different than this show. I had done three of them—we looked at the 1960s/1970s, the 1970s/1980s, and the 1980s/1990s—and afterward I thought, well, should there be a fourth? I thought that it would be more interesting to really explore what is going on with sound, in general, and to not do another history; other people have done that, and they have done it very well. I am sure there will be more historical shows. So, in keeping with what I have done in the past, including the Projects series and other kinds of things, I wanted to think of a younger generation.

I started thinking about this exhibition somewhere around 2010 or 2011. We had three large binders, and we did a lot of research—printing things out, ear-to-the-ground listening, downloading—and I had a couple of modest travel grants. I was fascinated by what was coming out of Scandinavia in particular, thinking that there was, you know, a lot of noise coming from that area. Why was that something coming out of Scandinavia? I don't know—I don't have the answers to that question, but it was on that research trip that I met Camille Norment, Jana Winderen, and Jacob Kirkegaard.

CE: When walking through the show and reading about these artists, it becomes clear that this is a decidedly international exhibition. Do you think that sound, or maybe the history of sound art, has in some way lent itself to becoming the global art practice that it is today, or does its international presence relate to a broader movement within contemporary art in general?

BL: I think that it is more related to a movement in general. But I am very aware that in Australia, during the 1970s, there was sound activity, and that in India there has been twenty years of sound activity. Maybe these activities did not get lots of nurturing, but people were working with sound. The same for Japan, as you well know, where there are many, many musicians, noise musicians, and some of them have done sound installation. People of your generation are now looking back to people like Yasone Tone, and just revere him for what he did, so it is indeed very international.

CE: Do you think that the rise of sound art, as a global practice, is in part related to new communications technologies?

BL: I think it is partly technology. We are able to communicate faster now, and we also have faster access. Maybe we are unable to bodily experience an installation by someone that is present, now, in Tokyo, but we will do everything possible to read a floor plan or a diagram, and, you know, we can imagine. I have also thought about—and this would be for another conversation—how my parent's generation, or your grandparent's generation, would have listened to Bing Crosby, and heard some sounds through writers, or maybe The Ed Sullivan Show, or whatever, and it was either this group or that group. Then with The Beatles and David Bowie, my generation had more sounds available to us, and now through the internet you can send your friend a playlist with all kinds of weird stuff—it builds and builds.

CE: The first time that we met you had just returned from the Venice Biennale. Have you found that sound is being given more consideration at these massive international exhibitions and art fairs in recent years?

BL I think it is. As you know, the wide-open terrain is always interesting to experiment with, and although you have galleries like Gagosian or Hauser & Wirth, where you expect to see certain things, you also have galleries like Tanya Bonakdar, which has Susan Phillipsz, and Luhring Augustine, which has Janet Cardiff and George Bures-Miller. And then other people are presenting their work in Bushwick.

CE: More people are listening?

BL: Yeah.

CE: I would like to take a moment and dissect the title of the exhibition. Where did the "Soundings" moniker come from?

BL: Well, I was really toiling with a title, and thinking, you know, the term "soundings" can bring to mind a sort of movement, a reaching into the deep to find out what is going on, an exploration—actually, that is very much what Jana Winderen has done. And of course I knew and had actually seen Suzanne Delehanty's exhibition, Soundings, at the Neuberger Museum in 1981. I am very sorry that I did not do a tip of the hat to Suzanne in the catalogue, because I was out of my head by the end of putting that together, but the title comes from this notion of exploration. The rest of the title is a sort of word play. It does not really refer to a score in itself, but rather a reading of what is going on. However, this exhibition is not the be-all and end-all, because I was limited by space—but it is a view.

Liz Phillips, Sunspots I & II, (1979-1981). Sound installation with stereo amplifier, two-ohm F loudspeakers, electronic sound-synthesis system, two capacitance fields, copper tubing, brass screen, copper ribbon, plexiglass, light sensors, and solar panels. Installation view from the exhibition Soundings at the Neuberger Museum, Purchase NY.

CE: The score is a very prominent theme throughout the exhibition. The term is in the title, but there are also several works that directly reference what we might call the musical rhetoric a score—that is, the types of practices, gestures, and materials that a score encompasses. This notion of the score, as a conceptual framework, has been a recurring theme in contemporary art for decades, and, in regards to sound art, calls to mind things like the event score. It also refers to a more general opening up of musical language in the 1960s, an investigation into the components and parameters of musical practice. This expanded history of the score bears its presence on the charcoal and ink works by Christine Sun Kim, which almost read like a text by George Brecht. What is the significance of the musical score for this exhibition?

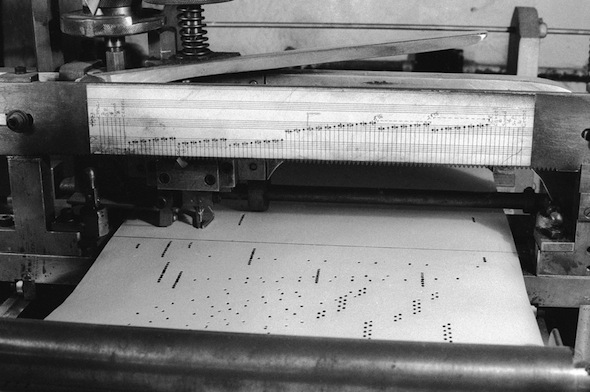

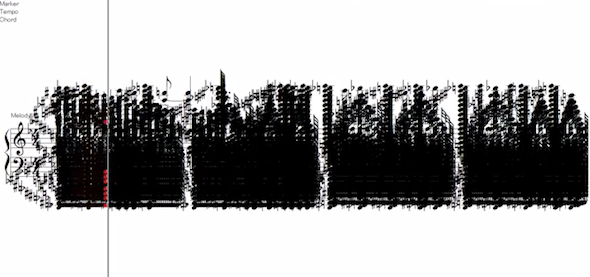

BL: I was lucky to visit Marco Fusinato in his studio, but I knew that if I put in one of his installations, such as Aetheric Plexus (2009), which has these rock event spotlights that blind you like a deer in headlights, and an incredibly loud noise, that it would dominate the entire floor. He showed me the series, Mass Black Implosion (2012), which references noise but is conceptual, and I thought that it would be a great way to include him in the exhibition. In this work, you are looking at an Iannis Xenakis score that is reproduced one to one, but Marco is pushing it somewhere else. Indeed, it is a score, and you can find all kinds of musical connections behind it, but it came out of this concept of taking the scores of major twentieth century composers, maybe forty of them for that series, who have a history, an impact, and then choosing a central point, drawing a line from every note to it, and really pushing it somewhere else. You look at the score, and you know that you will never hear it played, so it is conceptual and it is in your head. You have to look at it, and contemplate it—and that is what you do with any score, unless you are such an opera maven that you go and have the libretto and a score that is being performed. The opera allows you do that. These are beautiful drawings, and they are conceptual works that allow you to think about, as you mention, what a score is and what ideas are.

Top: Marco Fusinato, Aetheric Plexus (2009). Installation view, Artspace, Sydney. Bottom: Marco Fusinato. Mass Black Implosion (Shaar, Iannis Xenakis). 2012. Ink on archival facsimile of score, Part 1 of 5 parts, 32.3 x 43.1" framed. Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne & Sydney.

I think this is related to what Christine Sun Kim does. I often think of Hugo von Hofmannsthal's The Lord Chandos Letter (1902), in which he is writing about an author who decides never to write again because he can never achieve what is in his head. What is in his head is so much more profound than anything that he can get on paper. I think that Christine, in a way, is also thinking about these concepts—musical concepts, sound concepts, and language (which is the voice and a sound)—and I think that what she has combined on the page is just so beautifully poetic.

CE: Those drawings are very gestural as well, and call to mind the markings of, say, a painter like Jasper Johns—the objects, rulers, that he would pin down and drag across the surface. You can feel the movement of the hand, and, in a sense, the viewer replicates those gestures in their own mind. What is the role of the viewer, or listener, when encountering the works in this exhibition?

BL: Well, I think that it is experiential. You have to move around. You could say that sculpture is three-dimensional, and that, if you really want to understand it, you have to walk around and see it from all of the different angles. For example, the Luke Fowler and Toshiya Tsunoda piece, Ridges on the Horizontal Plane (2011), is durational because the slide and the film projectors are time-based, but the curtain also flutters in relation to the fans in the corner, and the work very much exists in real time. The audience can be observers, or listeners, but they really have to move around in order to fully experience the work. I think that you have to engage most of these works by spending time with them, and for many of them this means moving around, standing in front, and thinking about the experience. I have always felt, in all the years that I have been at the museum, that you will not be able to nail someone's feet to the ground. It is going to be a cumulative experience. In the moment, they might think, "Holy moly, yuck," but then they might go home and think, "Oh, maybe," or even see something at another museum and then come back to the exhibition. You will not get them to do anything against their will, but we can make the experience as commodious as possible. There is a bench, a soft seat, or a rug, and if you want to sit down on the floor, then you can go ahead and do that.

CE: I did notice that there are plenty of seating arrangements throughout the exhibition, and, in fact, some of the works explicitly invite you to sit down. I also noted that many of the works raise issue with the body, illustrating how sound affects the body and can define an experience, or even space itself. To that end, one of the things that first stood out to me was the relation of Tristan Perich's Microtonal Wall (2011) to the work of Robert Rauschenberg. Like Rauschenberg, Perich really plays with ideas about space and the body, and, using technology, calls attention to modes of spectatorship. The work specifically brought to mind a relatively unknown work by Rauschenberg, incidentally titled Soundings (1968). The two pieces are similar in that each is a large, elongated panel, hung on a wall, which engages the viewer through sound. However, Rauschenberg's panel is voice-activated, and, when the viewer speaks, the sounds of their voice triggers lights embedded inside, in turn illuminating an otherwise opaque work. In other words, the former invites you to make sound, and forces you to speak, while the latter forces you to be silent, and invites you to listen. Yet both are investigating the capacity of sound to construct experience.

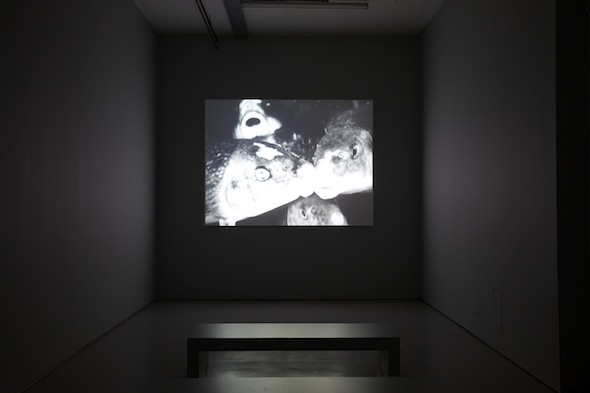

Robert Rauschenberg, Soundings (1968). Produced in residence at Bell Labs under the auspices of Experiments in Art & Technology.

BL: I believe that Tristan is certainly aware of that Rauschenberg work, but his practice, and the materials he used to make that piece—the electronics, the very simple 1-bit microprocessors, and the tiny, cheap speakers, fifteen-hundred of them placed in a grid—actually tips the hat to the Minimalists. The piece is there, front and center, as a way to get people to slow down, and to get people to listen, so we really did think about where to place the work. We could have put it in other places, but it is right there at the entrance of the show. People have to stand high, and they have to kneel low, in order to hear the four-octave range of the piece.

CE: Right. In order to really experience the work, you have to walk back and forth, and move up and down, so it is very performative. I suppose that you could just walk right by the piece, but then it would become white noise, which is probably fine.

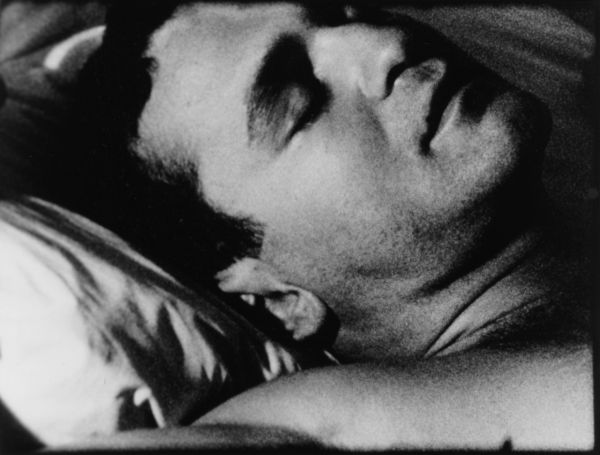

BL. Well, I think that in his exploration and in his experiments, Rauschenberg was celebrating, in a way, art and technology. He was one of the founders of Experiments in Art and Technology, and he was close to Billy Klüver, and Merce Cunningham, and this interest in performance makes for a sort of celebratory work.

CE: As a curator, sometimes you have to remove yourself from each individual piece, in order to realize an overarching or more general point of view. This can be a rather methodical, even dry process. Have you categorized the works in this exhibition in any particular way that would accommodate this type of curatorial labor?

BL: Sure, but I wouldn't call it labor. In thinking about the show, I wanted it to have texture. I did not want it to look like a Sony or Bose trade-room, or whatever, so I knew that it was not going to just be speakers and subwoofers. I thought about the whole conceptual side of it, the object side of it. Actually, before Sergei Tcherepnin did the Murray Guy show [Ed. - Ear Tone Box, 2013], he told me that he really wanted to make this piece, Motor-Matter Bench (2013), and we sat right in this room, went online, and found that you can buy a subway bench. So, the process was more like facilitating, or thinking of textures.

Sergei Tcherepnin, Motor-Matter Bench (2013). Wood subway bench, transducers, amplifier, HD media player. 28.5 x 20.5 x 126.5 in / 72 x 52 x 321 cm. Unique. Image courtesy of Murray Guy, New York. Photographer: Fabiana Viso.

CE: Do you find that sound lends itself to the sort of curatorial framing that other mediums have received in the past?

BL: Yeah. I feel that when we all think of art history, we think of contemporary practice, and we think of boundaries breaking down. There is structure, and there is content, and it can all be analyzed in different ways.

CE: I will play the devil's advocate: How can sound have content?

BL: I think that sound can have content because we all have lived with abstraction. All of these works have content in some way, whether it is Tristan Perich and his Microtonal Wall with its rhythms and patterns, or Florian Hecker, who also uses patterns, rhythms, and plays with this idea of repetition.

CE: In a recent New York Times article, art critic Blake Gopnik posited two strains of contemporary sound-practice. The first is aligned with representation, language, and cultural analysis; the second is aligned with abstraction, materiality, and the continuation of a Cagean tradition of experimental music. Gopnik also identifies works that represent each strain—the linguistic and the materialist—within the Soundings exhibition. How do you feel about these distinctions? Do these boundaries have any merit?

BL: Well, I think that all of these distinctions, definitions—and, you know, he is writing for the New York Times—I think that they are fine. But all of these terms are handles, and they are good for a moment. They are not the be-all and end-all, but it is rather a way of talking now. We know that the field is enormous and diverse, so, for him, he is not trying to make a Manichean distinction: it is this or that. I think that we can try to define sound art one day and it will be thrown out the next. If you are talking to a group that is unfamiliar with this type of work, then you try to help them along. But you also have to say, you know, this is a particular moment.

CE: Do you feel that sound has the capacity to become a critical practice? What would a critical sound art actually sound like?

BL: I do not know if it would be a sound at all. It might be a concept. I think that criticality can come in many different shapes and forms, and there is a lot of criticality out in the world. Maybe some of this work is obscure. You really have to work at it.

CE: I would like to end our conversation with some open-ended questions, which can be left for pondering. It is clear that, for the moment, sound has thoroughly suffused contemporary art. Increasingly, one is hard-pressed to visit an installation or performance and find a silent space. However, it also seems that many artists who use sound are simultaneously veering away from "sound art" as a discipline, and do not necessarily identify with its historical lineage. What do you see in the future for sound art as an artistic practice? Will sound become a long-term concern for the art world? Does sound belong in a museum? Will we ever see a department of sound and music at MoMA?

BL: Well, I have to say that this institution is moving away from those categories for exhibiting contemporary art. For housekeeping, you have to take care of a drawing or photograph in a particular way, but if you come after we do the next expansion, or even before, it is really just going to be contemporary. You might have, as you can see now on our second and fourth floors, a combination of different mediums together. There will probably not be a department for sound, but there will be people with expertise.

CE: Sound is here to stay?

BL: Yes, I think so. What do you think?

CE: Well, I think that sound has been here. It will continue to be here.

BL: Yes. Sound is here.

Charles Eppley is a PhD candidate in art history at Stony Brook University, where he researches the history of sound in modern and contemporary art. He currently teaches at Pratt Institute and Stony Brook University.

Barbara London is an associate curator in the department of media and performance at The Museum of Modern Art. Her recently opened exhibition, Soundings: A Contemporary Score, is open through November 3, 2013.

.gif)

The latest in a series of interviews with artists who have developed a significant body of work engaged (in its process, or in the issues it raises) with technology. See the full list of Artist Profiles

The latest in a series of interviews with artists who have developed a significant body of work engaged (in its process, or in the issues it raises) with technology. See the full list of Artist Profiles .gif)

.jpg)