![]()

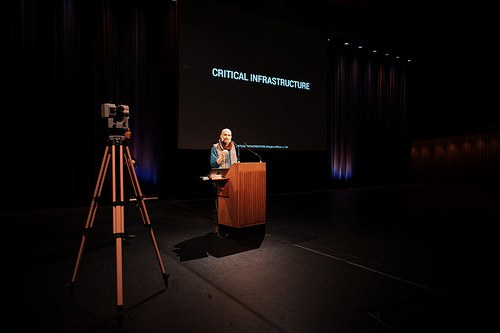

Beginning in 2009, artist Jason Simon worked with media scholar Cynthia Chris to investigate various distribution channels for artists' films and videos. This collaborative research has fed into Simon's own work, which draws on curatorial, documentary, and installation practices to reflect on the same issues of moving image circulation. In this interview, curator and writer Jacob King discussed this research with Simon in relation to his recent solo exhibition at Callicoon Fine Arts in New York (Nov 10 - Dec 22, 2013).

Jacob King: Can you tell me a bit about your project with Cynthia Chris and how it got started? It seems to me that, today, amidst both an unbridled expansion of the art market and a rapid digitization of moving images, there is an amazing degree of uncertainty as to how a given film or video might circulate.

Jason Simon: From Fall 2008 through Spring of 2009 I was living in Paris and teaching in Copenhagen, and I reviewed a show by a Danish artist named Pia Rönike for Bidoun. The show included her film Facing, from a Kurdish story, a black and white art house style dramatic featurette, which screened continuously in a Paris gallery. Although it wasn't a new phenomenon, I had never been more struck by this displacement of cinematic aesthetics into a gallery environment, and this started a long, slow percolation of questions about shifts in infrastructure.

At that time, UbuWeb was gathering extraordinary attention and dividing communities along lines of access and rights to historical and contemporary artists' media. It was in the range of responses to Ubu that I saw new positions being formed. How institutions and artists felt about Ubu in 2008 told you a lot about where things were going. I came back to the US and my job at the College of Staten Island, where I teach with the media scholar Cynthia Chris, someone who also has an extensive pre-academic and professional history with artists' media outlets like Women Make Movies, Video Data Bank, and Printed Matter, and we decided to pursue some of these questions together.

JK: What questions have you and Cynthia have been asking, and who you have been speaking with?

JS: The two initial questions I had in mind when I returned to the US were: what accounts for the differences between European and North American distributors in their relationships to non-academic partners like UbuWeb, galleries, and museums; and how does one see a video after it shows in a gallery? These are medium-specific questions about infrastructure, which are different from the more interpretive discussion that accompanied video's wholesale migration into fine art exhibition venues. In Europe, pre-recession public money permitted non-profit distributors who grew out of an education market to adapt quickly, to embrace UbuWeb, to partner with galleries in placing and supporting editioned video works in collections, and to stream their catalogs.[1] In the US, meanwhile, you had distributors resisting both Ubu's free-access model at one extreme and the galleries' economy of scarcity at the other extreme.[2] This [economy based on scarcity] was clearly not sustainable, and since then, in the global recession, you could almost say the worlds have reversed: public money has disappeared from so much of the European non-profit video world, while the legacy American distributors, at least the ones that are left, have been steadily adapting. As a topic it mushrooms enormously, but Cynthia and I managed to conduct interviews in this time of transition with artists and distributors and gallerists, which were useful for us, if quickly dated.

JK: I sense that much of the uncertainty you describe stems from a conflict between two economic understandings of a film or video: on the one hand, the cinematic model, where a fee is paid to screen a work (either in a single screening or "looped" in an exhibition); and on the other hand, the model which comes more from photography, where a work is "editioned," with the purchase of an edition of a film or video generally conferring unlimited screening and exhibition rights to the owner of the work (or to whomever the owner might "lend" his or her edition), without the payment of any fees to the artist. In film, this distinction is material: in the former situation, what is exchanged is a print of the work, while in the latter, it is a dupe negative, from which prints can be produced in perpetuity for the purposes of exhibition. But with HD digital video, no such material distinction exists—one digital file is just as "original" as another and can be copied indefinitely.

The overlap of these two models can result in some strange, seemingly arbitrary situations. For instance, a museum or small non-profit that borrows a work from a distributor like Lux or EAI would have to pay screening fees, while a commercial gallery that exhibits the same work, and offers it for sale in an edition, might pay no fees. I wonder, do you have a sense of when film and video began to be editioned? Or in the case of 16mm, when artists and galleries started selling negatives and not just film prints?

JS: Those two economic understandings you point to can be mapped according to how far or close the contexts are from both cinematic and pedagogical structures. The second contradiction you point to (that the non-fee paying venue has greater access to original or master quality sources) is yet another anecdote in just how byzantine and unregulated the art market is. The entire economy of gate-keeping distributors is rooted in analog, that is, pre-digital, culture. Breaking that mold without destroying their economy is the puzzle, and perhaps the solution lies somewhere in subscription streaming portals.

As for finding early examples of editioning media works, this is a popular scavenger hunt: most recently Erika Balsom, but others too, have been looking at this and other questions related to early video and artists' films. When Cynthia and I were at the Castelli archives at the Smithsonian looking at the distribution business papers, we saw a few instances in the 1970s where pricing of video works had interesting evolutions. The Chicago dealer Donald Young had an influence on the process, which you can see in his exchanges with Leo; Donald was a pioneer video dealer, and in his case I was very interested in the later evolution of Bruce Nauman's Good Boy Bad Boy. That piece is from 1985, the year that Castelli-Sonnabend Film and Videotapes closed, and is an edition of 40. The gallery staff was very helpful in determining with me that it was Nauman's first editioned video piece—but even saying that is fraught. Nauman had many unique moving image works and installations that preceded Good Boy Bad Boy, and he had an earlier vinyl LP of a video sound track that was a limited edition. And even GBBB was initially part of a larger unique installation. But I would still say that GBBB is his first editioned video work: in 1985 it cost $1,000, by '89 it was $4,000, and by the last time I asked at a booth showing it at an art fair it was $250,000. Art/tapes/22, from the mid-1970s in Florence, Italy, was also a hub for arte povera videos, videos coming from the Castelli-Sonnabend Videotapes and Films Catalog, and Bill Viola was actually working there. I didn't know much about them, but I saw sales certificates for tapes, some as unlimited editions for $200 or less, some as editions of 20 for $1,000.

![]()

Bruce Nauman, Good Boy Bad Boy (1985).

Important to me about Good Boy Bad Boy is that its release coincided with the closure of the Castelli-Sonnabend video catalog and its dispersal to Electronic Arts Intermix and the Video Data Bank. The main reason for the handoff was that Castelli-Sonnabend Videotapes and Films could not keep up with either the institutional demand or the changes in technology. EAI and VDB were just better equipped and prepared to handle the business, and built into that business was the fact that the necessary generational loss between an analog original and an analog copy was also a security; a bit of piracy protection and salesmanship that facilitated rentals of screeners and sales of heavier-duty archival sub-masters. But that security has been taken away by HD digital technology, and at precisely the moment at which these distributors were given the rights to a historical archive which could serve as a reliable source of revenue, artists started to distribute their works as editions, sold by galleries. Your example, that a work distributed by Lux or EAI could be obtained by a gallery for free and then sold by the gallery as an editioned work, is a particularly suggestive sequence of events; I would be interested in seeing new contracts or license agreements designed to connect distributors more with editioned works.

JK: Could you talk a bit more about the Castelli-Sonnabend Videotapes and Films catalog?

JS: So many of the artists showing with Leo Castelli and Ileana Sonnabend in the 1960s and '70s made films and videos that were central to their practices, and the galleries supported them by creating a spin off enterprise to handle that work: to manage the tasks of making and sending out copies and developing the catalog into its own business. That business followed the non-commercial film distribution model of lower cost rentals and sales for single screenings, at schools and libraries and museums and art spaces. Artists were paid royalties from the typical fees of $50 to rent a tape for a night or two, or $250 to own it. If you bought it, by the mid 1970s, you got either a reel-to-reel videotape, or (a little later) a 3/4" U-matic cassette, and in the case of a film you received a 16mm release print. If any individuals were collecting these then, it would have been rare; rather, most of the clients were non-profits or libraries.

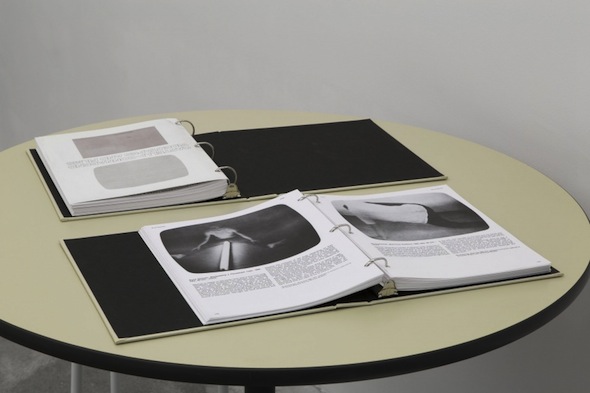

The catalog itself became a significant document of video's centrality to a conceptual vocabulary; it was three-hole punched and unbound, so it could be updated with supplements for new works that you added into your own binder. At first just the Castelli or Sonnabend gallery artists like Nauman and Vito Acconci and John Baldessari were included, but gradually it expanded with more filmmakers, especially more women. By the 1980s, the catalog was widely circulated to art and film departments at schools, as well as all the museums and sites where this work could be programmed: it was a standard reference. When I finally got a copy, from Bill Horrigan at the Wexner Center, the writing jumped out at me for its unadorned and attentive style. A number of writers covered the 16mm film entries, but all of the video entries were written by the filmmaker Lizzie Borden: she seemed to never use an adverb, and instead reproduced the observational style of the videos themselves when describing what goes on in the tapes. I was interested in the literature of video art publications generally—rental and sales and exhibition catalogs that took video's medium-specificity for granted, with all of the political, aesthetic, and technological assumptions intact. So many of these catalogs—the CSV&F, The Donnel Media Library, the Filmmakers Co-Op giant red book, Canyon Cinema, V Tape and Art Metropole in Canada, and the dozens of others that were standard reference volumes—now have this Rosetta Stone quality as the last printed compendiums to list and describe [artists' film and video as] a fairly contained culture before it exploded into an unfathomable ubiquity of artists' media.

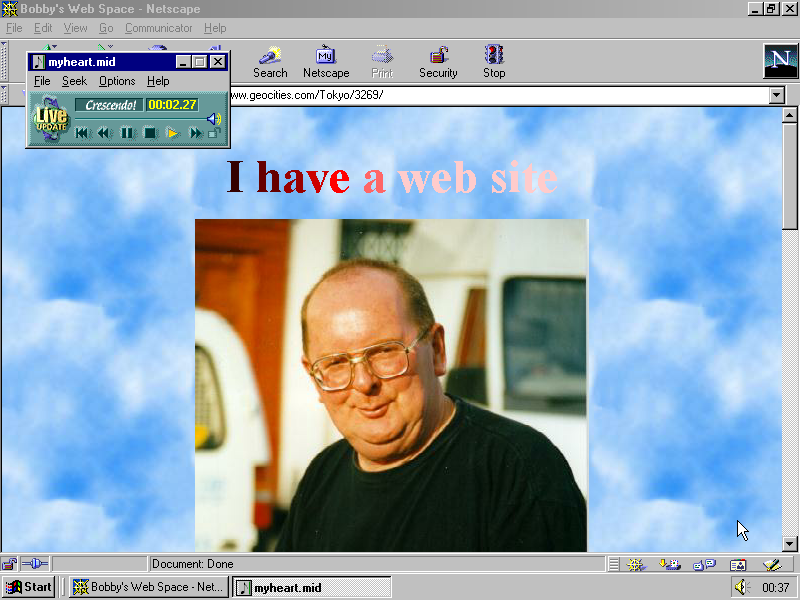

![]()

Jason Simon, Untitled (Castelli-Sonnabend Videotapes and Films), 2013. Facsimile of Castelli-Sonnabend Videotapes and Films sales and rental catalogue. Installation view, Callicoon Fine Arts.

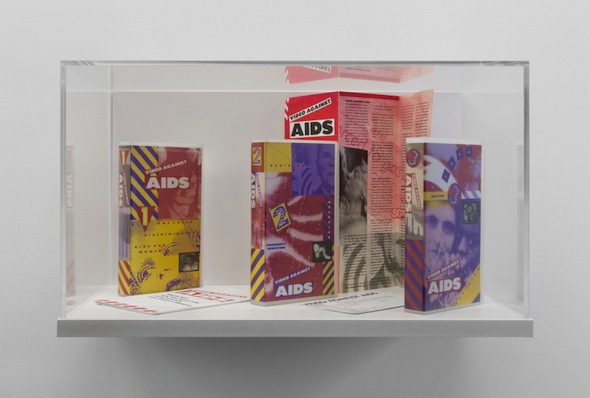

JK: Your recent show at Callicoon Fine Arts in New York included a facsimile of the complete Castelli-Sonnabend Videotapes and Film catalog which you produced as an artists' book. Alongside this you also presented a photograph of a 16mm film canister of Chris Marker's 1962 film La Jetée, which was distributed by McGraw-Hill Films for educational screenings, and the three Video Against AIDS VHS tapes from 1989, which are actually reproductions that you produced by scanning the covers of the original videotapes, now nearly impossible to locate (let alone purchase) because so many libraries and archives have trashed their VHS collections wholesale.

Each of these items functioned as an invitation to consider a superseded structure of film and video distribution, and a corresponding site of reception: the cinema, the classroom, the home. The final element in your show—actually a collaboration with Josiah McElheny—comprised five glass and wood "projection" windows which you installed in the rear wall of the gallery, and which made this white cube all of a sudden take on the possibility of becoming a cinema, and suggested various ways that galleries or museums now give shelter to moving images. In her recent book to which you alluded earlier, Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art, Erika Balsom stresses the relative novelty of this last possibility, and she cites the year 1990 as a kind of inflection point, with the introduction of digital projectors making possible expansive video installations that could enter museums and galleries on the scale of painting and sculpture. I wonder, what was the first video work that you exhibited in a museum or gallery space? How was it displayed? And how was it distributed or sold?

JS: The first video I showed was in the 1989 Whitney Biennial—it was called Production Notes: Fast Food for Thought and was a half hour tape about high-budget TV commercials that I had worked on.

Production Notes was selected for distribution by the Video Databank while I was still a grad student in San Diego in 1988, which was a precocious honor at the time, and for a long while the royalty stream from it was significant. But there was always an ambiguity about its circulation in fine art versus non-profit media circles. Museum curators would sheepishly tell me they were buying it for the education department because it was so popular in media literacy efforts of the time—I was clueless about editioning videos, but I guess by then they were already aware of the potential. It's a tape very much in the mode of 1980s appropriation art and commodity culture critique, but educators seized on it too. I also showed it that same year at The Collective for Living Cinema, when I premiered a collaborative film that I had made with Mark Dion, called Artful History: A Restoration Comedy, about fine art restoration. In both venues, at the Whitney and the Collective, before the age of affordable video projection, you had film screening rooms outfitted with CRT video monitors flanking the film screen and/or distributed among the seats on pedestals.

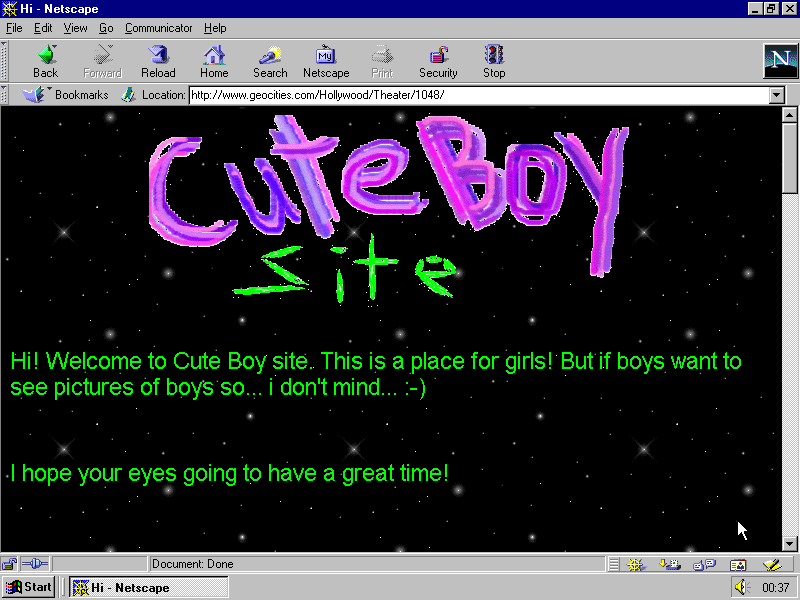

I mark 1989 as the year that film and video began to share screens, or, more precisely, venues, and as the beginning of the end of a self-contained media-art culture more or less independent of the art market. Video Against AIDS is also from 1989, and proved more and more fascinating as it proved harder and harder to find. The story behind these tapes is that Bill Horrigan (who is a regular source of inspiration for me), and John Greyson were commissioned by Kate Horsfield at the Video Data Bank to co-curate an ambitious program of AIDS activist media art. Important to understand about the context is the degree to which ACT UP and AIDS video was changing the landscape of film and video culture in general: you couldn't stand on the sidelines of the culture wars, and AIDS video was suddenly the prime shifter of media art culture. And with that program too, you had this booklet that accompanied the tapes, entitled "Using Video Against AIDS." Like Lizzie Borden's description of the earlier videos in the Castelli-Sonnabend binder, or like the discussion prompts printed on the inside of the film can forLa Jetée, these are writings addressing teachers. In all three you find this directed, intimate, discursive bond between avant-garde art works and a pedagogical economy. Bill and John did an amazing job of parsing the work and making a coherent case for artists taking on an urgent public mandate. But it was only distributed on VHS, and most VHS collections, even those in major libraries, have disappeared.

JK: In your show at Callicoon, I should point out, in addition to presenting reproduction of the Video Against AIDS VHS covers in a wall-mounted vitrine, you also screened the Video Against AIDS VHS tapes on a small monitor in the space. This strikes me as a means and site of distribution very far from the pedagogic economy for which these tapes were originally produced—for circulation to schools, libraries, and cinemas. If the gallery gives these no longer available VHS tapes a kind of visibility and contemporary life, I wonder what the trade-offs might be: what is sacrificed when these videos enter the white cube, digitized and looped continuously? I'm thinking of some particularly egregious (almost comical) examples I've seen: for instance, Chantal Akerman's Jeanne Dielman looped on a cube monitor (not even the right format for the image) in a summer group show at a gallery in Chelsea not too long ago. I'm sure we all have lots of examples like this. Sometimes I wonder if film and video is often shown in exhibitions less with the expectation that people will actually watch it—as in a classroom or cinema—and more as a kind of pointer, something to put on the checklist, to point at the work and perhaps to say something like, "go see this online," "ask for a screening copy," or, as in the case of the Akerman film, "rent this from Netflix." The internet is certainly the ground against which works in galleries and exhibitions are screened today, and the question is often, why show this in an exhibition space, and not online, on YouTube or Vimeo? How do you see this question? As much as I hate this word, do you think there is some quality or quantity of "attention" at stake here?

JS: The presence of Video Against AIDS on both the modest CRT monitor and in the vitrine grew out of the sheer difficulty in even assembling a visible version of that historic program. Once I found out just how lost it was, each element became supercharged and somehow necessary to declare in the show. It wasn't part of any early plan and I'm not trying to make it sound heroic—it was more just compulsive. But when you discover that all the people you know who are in the program, or who have even curated the program, have lost all or part of it, and that all the libraries (save one) that list it as current in their catalogs have actually tossed it away, well, it seemed important.

![]()

Video Against AIDS, 1989. Curated by John Greyson and Bill Horrigan, produced by Kate Horsefield at the Video Data Bank. Installation view, Callicoon Fine Arts.

The more systemic problem you're describing, that video is reduced to a mere index of itself in exhibition culture, is rampant and a consistent price for its inclusion in that context.

The complexity and contradictions of transposing film and video culture to gallery settings was certainly an active question within my show at Callicoon, especially with the projection booth portals that Josiah and I collaborated on: they appear both pictorial and light-transmitting at the same time and so set about to make that question tangible. I think it was also a subject of the show that you curated at Murray Guy last spring, "Screens." But while I was preoccupied with historical touchstones, you were sampling a contemporary range of work in which video was being turned into something else, a sort of text or sign of other forms of content. That difference is also tied in with your comment that: "The internet is certainly the ground against which works in galleries or exhibitions are screened today;" whereas I would have placed the word "cinema" or "videotheque" in place of "internet." That's a good example of a difference in where we might conceptualize the formation of an audience.

That could be a generational thing, but it is also why I was focused on the education market in both my show and in the research with Cynthia Chris. It was the demand from schools that ultimately closed down Castelli-Sonnabend Videotapes and Films: they could not keep up with the interests of teachers and librarians, but because VDB and EAI were meeting that demand and could continue to do so, they handed the whole collection over and got out of the business. I believe that that choice was really about how to do right by the works, how to keep them alive, and it worked wonders. Now there is an open question about how galleries respond to that same demand: if a student or a teacher needs to see a video that is only available from the artist or their gallery, it's anybody's guess as to how that plays out. Schools cannot afford to buy works from galleries the way they used to be able to from Castelli-Sonnabend, but perhaps the galleries have a greater interest in supporting that particular demand through online previewing channels and the like. If they don't make the work available, they run the risk of it being buried altogether by the sheer volume of artists' media work out there.

JK: In the show I organized last spring at Murray Guy ("Screens"), I was really interested in the question of how, when video (or film) moves from the cinema screen or digital computer screen to the white cube, a certain sculptural engagement is foregrounded; we can no longer pretend that it is some disembodied or virtual "moving image", but rather, it is a moving image displayed in a certain way, in relationship to the space, to viewing bodies, to the larger environment and the other objects and sounds. While it seems to me that much of the impulse behind displaying moving images in exhibitions stems from a desire to focus or bring attention to them—the power of the white cube to say "look at this!"—I was interested more in moving images that might move to the periphery, that might not ask viewers to focus within the space of a discrete rectangle, as in works by Rachel Harrison, Josh Kline, Neil Beloufa, or Georgia Sagri that incorporate video into larger sculptural arrangements. I have the sense that these artists (and many artists now) are responding less to the cinema or television and more to some of the newer ways that moving images are encountered today: in store windows and displays, on the sides of buildings, embedded in consumer products, or seen out of the corner of one's eye on a smartphone while walking down the street or riding the subway. But they are also responding to the real conditions by which film and video is often seen in exhibitions nowadays, particularly in the sort of large group exhibitions that often dominate art discourse. Viewing in these situations is often split: between the time/space of the exhibition, and a kind of retrospective viewing via a preview DVD or online link (or low-quality YouTube video). The experience of the work is really fractured, and this is especially true for people with more access to galleries (who can get links or online previews for whatever "content" they want). I can tell you, from working for a gallery, that it is not uncommon for reviewers to come see a show and, without even sitting through the complete duration of a video or film, ask for a preview copy that they can view at home. This context of distribution and viewing has to affect the content of the work being produced, no?

JS: This reminds me of a rule of thumb from those same pre-video projection days, when monitors were spread out around a screening room: every seat had to be within ten feet of a monitor, it was said, or else the video turned into a sculpture, which was a must to avoid! It also reminds me of Peter Wolen's 1976 essay "The Two Avant-Gardes," where he says something to the effect that the problem with artists' films in the USA is that they are too close to the art world, and too far from Godard. These anecdotes point directly to questions of content as long standing in these arenas, but that didn't seem to be a problem in "Screens," where, as you say, the artists appeared more concerned with deploying video as a sculptural element, scaled to our bodies, and temporally organized to our movement in space—foundational sculptural principles, anti-cinematic, but here given these superpowers of bringing the world into the sculpture. In my memory now, video in a lot of the works was a little like Superman's cape: magic and flimsy. I remain curious about the audience contract in cinema, which risks being a bit retrograde, but I think it persists in the art world as a broad reception fantasy for the work on the part of artists, a kind of new Stendahl syndrome, but at the movies.

Audiences can be created in all of these contexts, but there is a difference between an audience being created by awareness and an audience created by experience. In a gallery, distracted as we are and ruled by multiple levels of awareness, content gets sacrificed, as you've said. That makes the availability of these video preview options a mercy—maybe a mercy that gets abused, but understandably so. In my show at Callicoon, I was interested in proposing an origin myth for this imagined golden age of avant-garde moving image practices: finding a denominator in the education market as the material condition that made the avant-garde possible. It's a bit facile as a fact, like saying the Russian avant garde was about selling tractors and textiles, until you make the connection with this as a precondition of content.

New York

19 January 2014

[1] Here, Simon is referring to his conversations with Lux in the UK, Hamaca in Spain, and NIMK in the Netherlands.

[2] Here, Simon is referring to his conversations with Video Data Bank and EAI.