The latest in a series of interviews with artists who have a significant body of work that makes use of or responds to network culture and digital technologies.

Olivia Erlanger x Ned Siegel x NanoCorp, Suggestion of a House Slipper, The Refusal to get Dressed, Spending a Season Dreaming of Sunlight only to Prefer it Dark (2014)

Language plays a huge part in your work. The titles of works range from being exploratory—The Space Between My Hand and What it Holds (2014)—to almost explanatory (Olivia Erlanger x NanoCorp x Ned Siegel Suggestion of a House Slipper, The Refusal to get Dressed, Spending a Season Dreaming of Sunlight only to Prefer it Dark. Painted Leather Slippers, 2014), and are always poetic (Everything that Rises Sinks into Mud, 2015). How do you come up with these titles? How do you envision their connection to the work?

A title is a guide.

The first title you mentioned is for a pair of house slippers made out of leather. The show they were included in focused on marketing strategies and the financialization of art, so I wanted to make a reference to the way companies like Nike or Adidas cite their collaborations.

The other part of the title, The Refusal to get Dressed, Spending a Season Dreaming of Sunlight only to Prefer it Dark, is in line with the way I title most of my other works, in what you refer to as a more poetic way. Where this comes from is a mixture of research I had been doing and how I talk to myself about the work. These kind of titles begin to get a bit more evocative and associative —a guide for a certain kind of affect within the work.

Olivia Erlanger, For Quentin (Medium Rare) (2015)

Your work emphasizes its materials and focuses on the object, be it a transformed piece of clothing (cowboy hat, hoodie); a sculpture like a wilted, broken, mini-piano in your recent exhibition, "Dog Beneath the Skin" or the boxlike aluminum-and-glass racks that you presented at Seventeen last year; or and two-dimensional pieces (which also treat the material in a figurative way, and use sculptural materials like resin and aluminum). Yet, all of these photograph amazingly well. Do you plan how these objects are translated into an image? Do you think about how they will circulate online?

I don't make a work thinking of how it would be photographed, though I understand the importance of how images circulate ideas and current ways of making.

I think images of work can be misleading as they are always seductive. The real test of a work is if it can seduce in person.

Actually, It would be great to make an object that is impossible to photograph—a kind of atomic object that is simultaneously there and not there.

What is your research process like? Some of the works seem to refer to current discourses about the anthropocene and the role of objects in our society, but it is never stated outright. I have a feeling you read a lot and then allow the research to slowly be chipped away from the pieces themselves until they find a place in these conversations of their own accord. How do your interests feed the work? How is it independent of these interests?

I read everything from fantasy, such as the EarthSea series and sci-fi, to American Pastoralism, queer theory, and biographies of artists I admire. I do like to read theory and stay with current conversations around the anthropocene, accelerationism, etc.

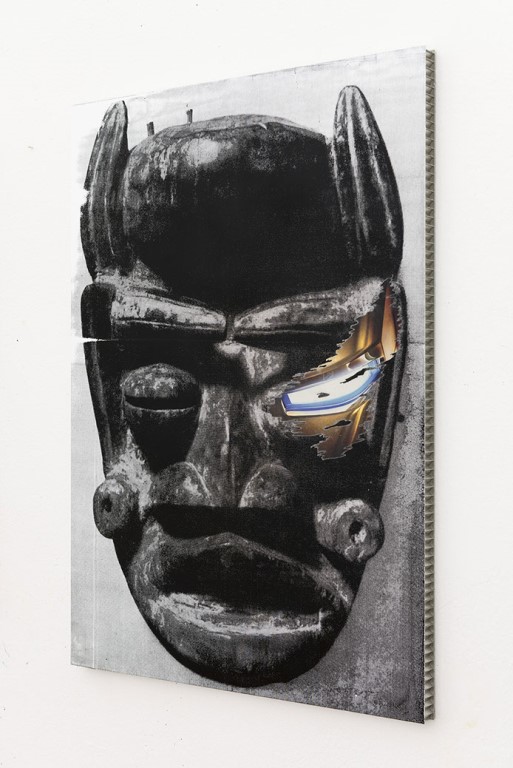

I have to say I am a bad scientist in the sense that I take only what I need from whatever theory I read, never the whole hypothesis. My work at times references specific things within what I read—for example, Timothy Morton's "hyperobject" was very important to my most recent sculptures at Pilar Corrias and Seventeen, as well as Paul Virilio’s idea of an "integral accident." I want to build my work to a place where the multiplicity of references and specificities of difference can be at once structured and unstructured within the works.

Olivia Erlanger, Floating Loop Strike Back Option (Alternative View) (2015)

Can we talk about time, even a feeling of zeitgeist? Your work is often discussed alongside that of other artists because of your interest in digital technology and the sense of community that your curatorial project, Grand Century (run out of your studio with Dora Budor and Alex Mackin Dolan) brings about. How do you relate to the work of your peers and how large a role does collaboration and curating play in your own practice?

We are all reacting to, or coming out of, a time of general disruption and confusion, and as such many conversations can meld or be related. I don't believe we are creating the Zeitgeist, rather, the zeitgeist is structuring the moment in which we create.

With regard to Grand Century, it has fostered a wonderful community of curators, artists, friends. Being involved in the space definitely helped me get a broader sense of what is happening amongst my peer group. I would say I am most indebted to the project because each curator brought in artists whose work I had never been exposed to before.

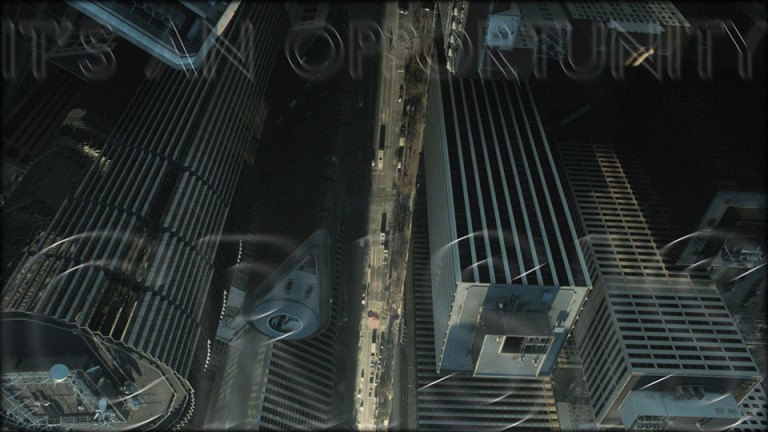

Olivia Erlanger, TANSTAAFL (2015)

Before we get to the questionnaire, let me ask you about this format. You've worked quite a bit with the questionnaire, in the book produced as part of "Material Uncertainty" and in your BOMB portfolio(which we worked on together). I want to ask you about questions: Why do you use this structure? What do you find interesting about it?

I like questionnaires because they are ubiquitous, procedural, and seemingly innocuous.

In fact I think the best part, beyond the satisfaction of answering what are usually simple questions, is the spaces that this kind of format recalls—sitting in a doctor's office, renewing your license at the DMV, the beginning of the SATs, or contributing to the Census. A questionnaire's simplicity and directness is actually very suspect, and in that sneakiness it can be exploited easily to elicit ambiguity and some really nice thinking.

Olivia Erlanger, Look, Stranger (2015)

Questionnaire

Age: 25

Location: NYC

How/when did you begin working creatively with technology?

Do pencils count as technology? If so then some time from 0–3.

Where did you go to school? What did you study?

Lewis and Clark College + Parsons School of Design / Eugene Lang. I graduated with a double major in sculpture and English literature.

What do you do for a living, or what occupations have you held previously?

I've been a florist, gallerina, receptionist, waitress, file manager at a startup and of course a studio assistant. The only career I seem to be able to hold is my own.

What does your desktop or workspace look like? (Pics or screenshots please!):

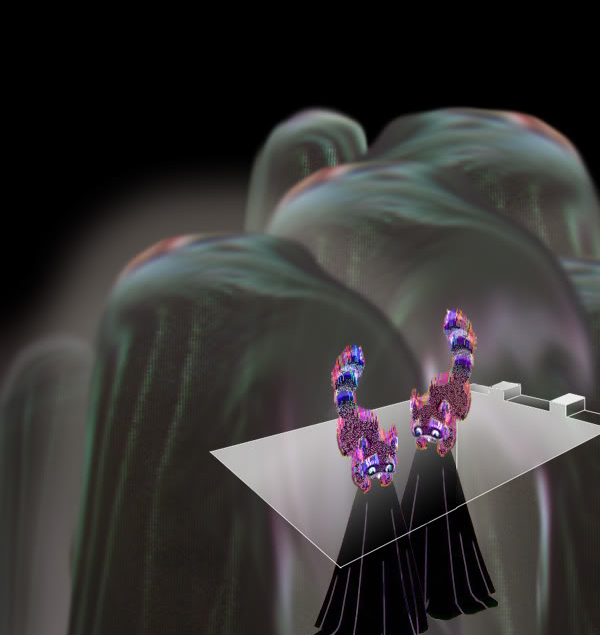

2015 Prix Net Art Winner Constant Dullaart. Photo by Ethan Hayes-Chute.

2015 Prix Net Art Winner Constant Dullaart. Photo by Ethan Hayes-Chute.