"Somehow I got tenure for all of it and got into trouble for all of it at the same time." Throughout a long and varied career, Ricardo Dominguez has made artistic and poetic gestures that trouble and confuse the powers that be. Now an Associate Professor at UCSD, Dominguez recently sat down with Ash Eliza Smith for a conversation about his life's work so far, the power of critical aesthetics, and why the FBI is looking for Walter Benjamin.

Hauntings, a 1997 collaboration between Dominguez, Francesca da Rimini, and Michael Grimm, is featured this week on the front page.

AES: As a part of activist media art collective Critical Art Ensemble in Tallahassee, Florida in the late 1980s, what prompted you to move to New York in 1992?

RD: When I moved to New York City my main focus was to try to get access to infrastructure and computers. In the '80s with Critical Art Ensemble, even though we had theorized electronic civil disobedience, electronic disturbance, and the performative matrix of data bodies and real bodies, we didn't really have computers in Tallahassee, Florida and so I thought that in New York City there would be a greater opportunity to meet communities that had access to this kind of infrastructure.1

![]()

Critical Art Ensemble, L-R: Steve Barnes, Ricardo Dominguez, Hope Kurtz, Steve Kurtz, and Dorian Burr, Tallahassee, FL, (1987)

AES: How did you get involved with the net art scene that was happening in New York in the early '90s? How did you meet people?

RD: Part of the early work was that I would roam around SoHo and read The Village Voice to see if anybody mentioned anything that had to do with computers and art. One day I was walking along and I saw a poster for Sandra Gering Gallery in SoHo that had a MOO space address [a text-based virtual world] and I thought, "there seems to be something about technology, so I'll go to the show." It turned out it was an exhibition by Jordan Crandall and there was nobody there except Jordan, so I went up to introduce myself and told him that I was from Critical Art Ensemble. I was interested in these questions of the digital and the performative matrix and I thought his show seemed to indicate a kind of exploration of that emerging territory. We had a really good conversation. Some of Jordan's work at that time was around trying to expand the definition of object, text, and publication forms when they encountered new modalities of distribution. He was doing a project called Blast, which was an experimental publishing form that explored these kinds of digital encounters between object and text. There were very beautiful boxes of artworks created by multiple artists, and there were also discussions in these MOO spaces. Jordan invited me to come visit him at Blast, which was in the East Village, where he introduced me to Wolfgang Staehle who ran the thing.net, an Internet Service Provider (ISP) for artists and activists that started in 1991.

Wolfgang Staehle was not only an important figure, but also a visionary in thinking about infrastructure as social sculpture a la Joseph Beuys. Staehle had made his money in the '80s as a conceptual artist, and so it was very difficult for many of his peers to understand why he had a bunch of modems down in the basement and what that had to do with art production. The great thing about Wolfgang was that he didn't really care about what you were doing as long as you were doing something, so he basically left me alone and said: "Here's how you get people online, here are the books, and here are the machines" and so I would just go hang out and teach myself how to be a systems administrator.

![]()

Exhibition flyer for "In the Flow" (1996)

AES: Were you still active with Critical Art Ensemble at the time?

RD: To a certain degree. I left CAE around '94-'95 once I started to develop [activist performance art group] Electronic Disturbance Theater and started working with the Zapatistas in '94, because that really shifted the way we conceived of electronic civil disobedience; it was no longer just a cadre of high tech figures who would develop this stuff. The Zapatistas really taught me to think otherwise, that one could be transparent, poetic and create disturbances that were not really based on any kind of quality of technology.

In 1993, Mosaic [the first widely used web browser] came along, then NAFTA occurred, and with the beginning of 1994 at one minute after midnight, the (Digital) Zapatistas emerged. The next day at [NYC cultural center] ABC No Rio, we started the new Committee for Democracy in Mexico and the New York Zapatistas because we were all getting emails all night long from midnight to 6am. The Zapatistas basically sent emails like a machine all night long. It was glorious. The New York Times said that with this event, the first postmodern revolution had occurred.

AES: How did being a systems administrator at the thing.net inform or change your art practice?

RD: As a systems administrator, people would call me up to get online and I would go through the elements they needed: a modem, encryption…in those days it was not easy and sometimes it might take two-three weeks to get online. We had a thing Berlin, a thing Vienna, a thing Amsterdam, New York, Cuba, la Cosa Argentina, so it was quite a large system and a great training ground where we were then able to establish HTML conceptualism with the browser.2 I was also an editor for Blast 5 (part of a series of experimental gestures initiated by artist Jordan Crandall in 1990), and at the same time I was meeting a lot of different communities of artists and critics as a part of the Williamsburg scene in the '90s.

![]()

AES: Who were some of the art collectives that you worked with during this period?

RD: Well we would hang out at the Void, one of the first underground digital clubs, right off of Houston. There, performing in the club, I met the group Floating Point Unit, who were doing a lot of early body scanning, improvisation, music, and immersive digital gestures. We worked together to do a series of public TV episodes around the question of data bodies. There are like 12 episodes that aired on public TV. I also started working with the McCoys (Jennifer and Kevin McCoy) and they would do things like put headphones on me and have me watch a Starsky & Hutch episode. People would gather around me and I would interpret what I was seeing to them. I also worked with [anti-shopping performance artist] Reverend Billy, [early online broadcasting platform] pseudo.com, and [net artist] Robbin Murphy and others to do these kind of crazy early streaming radio shows. Robbin Murphy curated PORT at MIT via his platform a r t n e t w e b, and he was also part of Art Dirt the online radio show where I did Rabinal Achi/Zapatista Port Action at MIT with artist Ron Rocco.

I would perform an extant Mayan play about the battle between the Rain King and the Corn God, and I would use that as a space to have conversations globally about the Zapatistas initiating electronic civil disobedience. That’s how I met the artists who would then become Electronic Disturbance Theater (EDT). I met Brett Stalbaum, who was a new media artist in San Jose, and Carmen Karasic because she was running the servers at MIT, and I had read Stefan Wray’s thesis on the drug war/information war in Mexico. Floating Point Unit became [audiovisual performance project] fakeshop.com, and that's when I met [author and philsopher] Eugene Thacker. We would do huge installations and early science fiction shows like Fahrenheit 451 or Coma State in Williamsburg. There were these large immersive environmental digital gestures that often no one ever went to, but they were occurring there in Williamsburg. All these different elements came together, which would become the emerging New York city-based net art communities.

Later in 2000, we did the Warhol hijack where Yael Kanarek convinced Josh Harris and Tanya Corrin to turn over their luxury loft to our group (Yael, Jennifer Crowe, Tina LaPorta, G.H.Hovagimyan, Diane Ludin, McCoys, Robin Murphy, Cary Peppermint, MTAA). Harris was the guy from the movie We Live In Public and there were cameras all over his house—surveillance devices that we were able to use for the weekend to do a show.

![]()

Warhol hijack (2000)

AES: Were you also collaborating with net artists in other places around the world?

RD: Yeah, I started working with [cyberfeminist artist] Francesca de la Rimini (gashgirl) while she was swimming in a pool in Japan and I was at a party in New York. Akke Wagenaar (Radikal Playgirls) wrote The Women I LOVE After Dark and had made one of the first websites about women who were doing early porn and post-porn stuff. Francesca was one of them, as a founding member of VNS matrix, the founders of cyber-feminism in Austria. I decided that I would interview everyone on the site, and shortly after that Francesca and I began a public transparent electronic love affair project. The project was called Hauntings, and in it she became Doll Yoko. The site contained all of our email exchanges and it had early sound. I haven't changed my website since the very first browser so there a lot of things that don't even function anymore. There's another one that Doll, Diane Ludin, I and a number of others did entitled los días y las noches de los muertos (a ghost work) by los fantasmas. It is using early kind of frame stuff and was much more political. This was during the alter-globalization action in Italy when a young man was killed—it's just early HTML stuff. Doll Yoko was the core artist and code scrapper. I used to write a lot of reviews under different names. I started writing stuff about the Zapatistas under my own name around that time.

AES: Do any shows really stand out for you?

RD: There was one show, "Teleport Diner" where this guy came to us at Diner in Williamsburg, where we always hung out at the time, and said: "Hey, I'm going to take this entire diner to Stockholm." They told us to meet at Diner and they would pick us up in limos and fly us to Stockholm for something like 24 hours. So we were like, “Sure let's do it!” And sure enough we found ourselves in a contemporary art space with plexiglass all around us in a recreation of Diner in Brooklyn. It was our job to just hang out and do what we did at Diner. For 24 hours we were drinking, eating, making shows up, but at the same time it was a weird space because someone told us people were suffering from Sun Madness (too much daylight). When we were heading to the airport, our bus started going backwards against traffic and then someone on the bus told us that the pilot had jumped from the plane and run into the forest. They would have to divide all of us up and send us on different planes back to the US. Unfortunately this meant that we got back to Newark at one o'clock in the morning with no money because we were internet artists. Finally we talked a family into driving us back to Diner in Williamsburg so that we could pay them.

![]()

Flyer for "Teleport Diner" (2000)

AES: What were some of the ways in which your involvement in the New York internet art scene coalesced with your work with the Zapatistas?

RD: I'd already theorized with CAE about electronic civil disobedience, and the real question was how to do it or how to put it into practice. The Zapatistas said to do it poetically, and so it made sense to function within the net art scene because that would then create the kind of aesthetic confusion that would make it very difficult for the powers-that-be to stop anything. Which was the case because basically they would ask: "Who’s hosting this virtual sit-in?" And the answer would be: "MIT or Rhizome," which was confusing. I was doing EDT as my own thing because I was the only one [of the collective] in New York, but at the same time I was working with these different net art communities of which Rhizome was one community among many layers of communities. Williamsburg was open territory because it wasn't congested at that moment, and it allowed us to play there.

We launched Disturbance Developers Kit [a software tool used for electronic civil disobedience] one minute after midnight in 1999 from a Fakeshop show. These kinds of informal situations allowed for the amplification of each other’s work within the nested projects of things that were occurring. The most important aspect of the encounter with Rhizome and all of the net artists was that it was a part of nested series of cultural spaces; many of the same artists were moving through those territories and sometimes there were arguments, but in the end but all of those moments came together to create a larger scene where things were amplified in wider ways.

![]()

Ron Rocco and Ricardo Dominguez, Rabinal Achi/Zapatista Port Action (1997)

AES: So how did you put electronic civil disobedience into practice with EDT and the Zapatistas?

RD: Well, It's not like the Zapatistas marched down from Lacandon and said: "Ah! We are going to rip into the electronic fabric of cyberspace and become an intergalactic network of struggle and resistance." They were a Maoist-Leninist group armed and ready to die in the tradition of Latin America, but they very quickly understood that something else had occurred when they ripped into the electronic fabric on January 1, 1994 and that civil society was now reconfiguring how they themselves imagined encountering the Mexican government – as war machine, as opposed to distributed data-bodies: Zapatistas in Cyberspace. There were ten days of battle and then they marched backwards into cyberspace. I thought "this is where electronic civil disobedience should occur"; I felt that the Zapatistas had pointed to this kind of nexus that we needed to focus on.

AES: Were you still working out of thing.net still, or how did you pull off the work with the Zapatistas?

RD: I had become the CEO of a company called Star Media Broadband and I had a huge loft on 5th Ave and 10th/11th. I had servers all over Latin America and we used that against the Mexican government. The company was all vaporware. We had a conference at nettime that was a special critical theory gathering and we knew that it was all vaporware…that it was all going to blow up. It was interesting to participate in multiple scales of cultures because Silicon Alley was not too far from thing.net and so we were all there in the same location. In '99 the toy war happened, etoy, the Information war happened, the battle with the Department of Defense happened with EDT and we were on the front pages of the NYT. It was a constellation of cultural encounters and explosions but still a small scene.

AES: So how have the ideas of embodiment and networks shifted in your work as you have moved through these different kinds of roles and scales from CEO to system administrator to artivist with CAE?

RD: Well, I think one of the elements that emerged out of the Critical Art Ensemble is that in the '80s we began to speculate that there would be a growing relationship (and not always in a positive way) between data bodies and real bodies, and that data bodies would be the indexical authenticator of value as opposed to what we might call the "real body," and that as virtual capitalisms became integrated in the early nineties through the ascension of infrastructure, networks and code, that we needed to instantiate forms of artistic practice that would disturb the conditions of rapid integration of value of the data body.

![]()

The Therapeutic State, edited by Critical Art Ensemble (1994)

There had to be other ways to encounter, conduct and re-configure protocols that would allow for new forms of embodiment, of being, of becoming, of enunciating, and of coding. The Zapatistas and Digital Zapatismo really articulated in a clear and direct manner how one could create a network, how one could establish infrastructure, how one could pre-configure or reconfigure code and the data body in relation to other embodied "social relationships" and "information systems" that were not bound to virtual capitalisms. In fact, we are/were naming the sites of deletion against what the Zapatistas called "the neoliberal world." I had never heard of neoliberalism until the Zapatistas clearly spoke about it.

For us it was NAFTA and the utopian integration of free trade (which is another form of virtual capitalism), but the Zapatistas also brought to the fore that it was a new re-definition of political ideology; at the same time, the Zapatistas really allowed us to be able to think—at least in terms of the community that I was involved with, of a type of critical aesthetics that could be constructed and manifested in ways that the imagined social infrastructure of virtual capitalisms couldn't respond to coherently or directly because it was somewhat outside of their field of understanding.

AES: Can you expand on what you mean by critical aesthetics here?

RD: That is in order to do these sorts of things you needed to have deep technological knowledge. (No, you didn't.) You needed to have the aggregation of a specialized semantic discourse—that is, you needed to know software. (No you didn't.) That you needed to have electricity, telephoning, computing in order to activate networks. (No, you didn't.) That's what the Zapatistas very quickly enunciated. So EDT for me was a way then to take the simplest conditions: HTML code and the public agora of the browser reload function. It's not like you're trying to establish a whole new protocol, you're just hitting the button over and over and you're using 404 files—files not found—which is already part of the integration of browser culture and was already under investigation by net.art or net (without a dot) art. You had groups like jodi.org who were investigating 404 files in a Dadaist way. Then it was easy for EDT to code switch the Dadaist modality of the 404 that jodi.org was doing towards this kind of critical aesthetic. Does justice exist at the government website?

Our practices of net art and the emergence of new forms of critical theory were about establishing gestures, vocabularies, and poetics against the kind of neoliberalism that the Zapatistas spoke about. All those things occurred, and perhaps the difference was the rapidity of being able to access all of these conditions from the very local of Williamsburg to the very global networks, to the critical poetics structures of the Zapatistas to sort of triangulate a kind of global condition—whether it was global or not is another question, but it certainly carried an imaginary that my email could have a conversation with somebody in Adelaide Australia so that I could communicate the issues of what I was doing there. Not that everybody was ideologically coherent in being a Zapatista, but they weren't necessarily antagonistic against it. They might not directly manifest electronic civil disobedience, but they weren't antagonistic to it because they saw it as part of this wider territory of net art or network arts, however you play it out.

I think that you see this to some degree in etoy’s Toywar gathering of late 1999 [Toywar was a coordinated effort to reduce the stock price of etoys.com after the company successfully sued the Vienna-based art collective eToy in a California courtroom for the rights to their domain name]—all of the things coming together, the communities of net art, electronic civil disobedience, redefining the politics of infrastructure and what art had to do as an activation that sort of ripped into the fabric and altered forms.

![]()

Toywar (1999)

AES: So after this first period, which seems focused around electronic civil disobedience, what directions did your work take? How did your work move into projects dealing with toxicology?

RD: The '80s were an important space for navigating and articulating ways of thinking, and doing and showing that the nineties allowed us to put into practice. In 1986/87, three sort of categories of critical aesthetics became important: 1) Virtual Capitalism, 2) Electronic Civil Disobedience, and 3) community research initiatives, which came out of our work with ACT UP Tallahassee. The human genome project also started in the mid-'80s, so there was a sense that there was a recombinant power and that clone capitalism was going to be manifested in a clear way in the '90s. So we thought that community research initiatives a la ACT UP would be useful to disturb this enclosure of the genetic levels of the body. In the days to come we would see the valuation of data bodies above real bodies. So yes, your authentic body had value for the corporation when they owned your disease, your alcoholism, your cancer; so we thought that we needed to do work in that area.

Hope Kurtz and Steve Kurtz of CAE were focused on clone capitalism, and they of course got into horrific trouble with Homeland Security who accused them of being bioterrorists. Hope Kurtz passed away unexpectedly and this led to the investigation that this initiated. Steve just wanted medical support for Hope and the medical team reported that Steve had a potential "bio-weapon" in his living room—that in fact was an artivist project being prepared for an exhibition, TheInterventionists. Steve Kurtz had to go through four years of legal hell and ultimately they won, but that particular trajectory comes from an earlier period and the emergence of wider hacktivism.

Right after we released the disturbance developers kit I really felt that I wanted to focus on particle capitalism, which meant that I needed access to atomic force microscopes, etc. The Warhol Foundation did not want to give any money for that, and the military didn't want to give me access to nanotechnology, and corporations didn't either, so I was in a bit of a state of consternation and concern as to how to move forward. I had gone to New York with a particular vision and process, and now I was at the next stage; I needed a different sort of infrastructure and support.

AES: So is this need for nanotech infrastructure was what brought you to the research institution/UCSD?

RD: In 2004, [artist and UCSD professor] Sheldon Brown called me and said we have this new trans-disciplinary space called Calit2, and so I went to propose a plan of research. The main part of my ten-year research plan would consist of three things.

One, Electronic Civil Disobedience and hacktivism; with this, the two main questions were: What does it mean to use UC computer systems against nation states, corporations, and social entities that we feel need to be disturbed via electronic civil disobedience or hacktivism? And I thought an even more important question would be the history of social critique, institutional critique, so I was interested in what would happen when I used the UC computer systems against the UC system itself. And so that would really be the core of the research. What would everyone say or do when that occurred?

Two, the next level of research would be border disturbance technology. There's a long history of border art in San Diego/Tijuana. I knew some of that history, and I thought that I would want to participate in it. I knew that there would be technology involved but the border would also be involved, and it would be about disturbance.

And three, the other area of research would be nano-poetics and interventions into nanotoxicology. I was interested in the way particle capitalism had removed the focus of nanotechnology away from everyday, unregulated use towards the utopian idea that we're going to cure cancer—the way that technology is always sold—or the apocalyptic, that the military is going to weaponize it. I have nothing against utopian therapeutics and there's not much I can do against weaponization, but we could focus on the everyday use. That is, Whole Foods wraps its food using nano-silver to keep it fresh... the products are just growing in terms of nanoscale technology—it's not high-end, it’s not artificial, it's just there, using nano-scale silver and nano-scale gold in socks. Hugo Boss said "Nano is the New Black" because he can create socks, pants and shirts that you would never have to wash because they have nano-silver. But the question was, why weren't there long term studies of nanotoxicology being done?

And so out of that came the Particle Group which was Dr. Amy Sara Carroll, artist Diane Ludin (who I had worked with in Williamsburg) and Nina Waisman who was in the MFA in the visual arts program. We were able to create a series of tales of the matter market that focused on intervention into the nano-technology labs themselves. These speculative poetics are aggregated at the Hemispheric Institute, which has all the projects that we did from 2007-2012.

AES: How did Transborder Immigrant Tool emerge within your focus of border disturbance technology?

![]()

Transborder Immigrant Tool concept showing working tool and screenshot from Nokia e71 (2000)

RD: My long term collaborator Brett Stalbaum and his partner Paula Poole lived out in the desert and liked go on very long, dangerous hikes, so they created a virtual hiker, an artificial system that pre-fabricated a Virtual Hiker using GPS.

In 2000, the military released GPS to civil society and with it came a lot of locative media art projects that I've never found particularly interesting—they were all mostly urban-based or tell narratives or stories, but I thought that Brett’s gesture was dislocated into this other territory. So that afternoon I asked if we could turn it into a GPS to deal with immigrants crossing the desert, and he said "well we have to find a cheap platform;" I went home and wrote the Transborder Immigrant Tool Manifesto and in it I stated that poetry should be a part of the project. Poetry has always been a part of all of the work I have done. I had worked with Dr. Amy Sarah Carroll who is not only a scholar of the border but is also an experimental poet. I asked if she wanted to write poetry for this machine, and that really helped us move away from the positions of locative media projects based on GPS to a geo-poetic system about sustenance and experiments of geo-aesthetics for the refugees and immigrants who are often seen as live zombies that cross the border to take a job and who have no cultural understanding of poetry or sense of cultural experimentation. I thought that I would code switch those things.

The project blossomed very quickly and we won an award in Mexico. After I did an article with Vice, within 48 hours we came under investigation by Congress, Fox News, and the FBI. All of these things aggregated to become the Transborder Immigrant Tool performative matrix between chaos and art.

AES: Glenn Beck said in 2010 that the Transborder Immigrant Tool was a gesture that potentially "dissolved" the U.S. border with its poetry. You’ve mentioned code-switching, scientific narratives, and the importance of disturbing through language and poetics. It seems that in everything that you've done, language has been very important.

RD: The notion of critical aesthetics has been the core conceptual driver for all the gestures and collaborations that I've been a part of; while they carry activism, artivism or the language of social engagement, it’s always been produced—with very rare exceptions—from a collaboration between artists. To me that becomes the manner which we can then begin to think about, "What does art do, that activism or engineering or design do not?" or "how does art move into the territory with a different set of questions and processes?" For me the consistent, coherent way to develop work is the notion that art is a type of thinking, doing, saying, and showing which is manifestly different from other territories of saying, showing, doing, and constructing. This gives us a way to establish different territories of dialogue and measurements of power that are not easy for power and its various institutional guises to shut down.

AES: Can you give an example of how this works?

RD: With the Transborder Immigrant Tool we thought, "well, what is the first thing the FBI would ask?" "Who has used this to cross the US-Mexico border?" So we were in Spain at an electronic poetry conference and we were wandering around in the middle of the night. We encountered Walter Benjamin Park, and we thought, "what if we went to Portbou where Walter Benjamin had committed suicide because he wasn't allowed into Spain from France?" We thought, "what if we go there with the Transborder Immigrant Tool and imagine the tool as a way to suck back the spirit, take him into Spain and then into Mexico (because he was supposed to go to Mexico) and then up to LA to meet Adorno and Horkheimer?" So when the FBI asked, "who has used the TBIT?" we said, "Walter Benjamin" and they wrote it down. So there you have a kind of poetic gesture where you can clearly say that somebody used it to cross the border and it was this person that they wrote down. I would imagine that the FBI is looking for Walter Benjamin at this very moment for having used the tool to cross.

So one establishes a kind of dis-temporality—a dislocated media that enunciates an aesthetic condition that disallows power from establishing its conversation in the manner that makes sense to it. "You hacked into a telephone, that’s illegal"—but suddenly they end up having to read poetry. “Is the poetry encrypted?” All poetry is encrypted as far as I know. They have to end up discussing "What is Duchamp?" "What is queer theory?" "What does the trans have to do with anything?" It is here that you detour power into conversations that it's not prepared to have or doesn't want to have, and so they become aesthetically confused. For me that's how that performative matrix works. If we were activists, or cracktivists, or engineers, then the focus would be on establishing that this tool functions in an effective utilitarian manner that goes in a linear direction. But our approach is, "that's not the way to do the work."

AES: But you also simultaneously do the reverse in terms of arti-scientist thinking about the simulation of the laboratory to become the artist laboratory space.

RD: Yes, this goes back to community research initiatives. The "Science of the Oppressed" that I took from Monique Wittig, the feminist philosopher and science fiction writer, means we can create community research initiatives that imagine effective processes of research, but always attached to that effective process of research as affect. And so, as one scholar has pointed out to me, the work that we do joins the A and E together so you get aeffect, in that the tool does indeed work.

AES: Like with the Transborder Immigrant Tool, for example?

RD: Yes, because NGOs such as Water Stations and Border Angels would not allow us access to the water cache locative waypoints if we didn't show up. The virtual sit-in does function, but it functions in ways that don't necessarily anchor themselves to that functioning as the primary condition by which one defines the work.3 So code and poetry for us are one and the same. The aeffect of the poetry is equal to the aeffect of the code. So you can’t say only that the code is effected and that the poetry is affected because it's actually a melded kind of condition. One can imagine the notion of the laboratory to be reconfigured towards ends other than what one imagines the research laboratory to develop. I do think that part of our job is to reconfigure the way art is being produced within a certain kind of loci. I've been lucky enough to work in multiple highly intelligent, collaborative situations and I think that has been a guiding element in the work that I've done.

![]()

Zapatistas' strike on the steps of the New York Public Library, 5th Ave at 42nd St, New York, across from the Mexican Consulate (1994)

![]()

Ricardo Dominguez at the Zapatistas' strike (1994).

AES: So what’s next on the horizon?

RD: I think if you had talked to many of the people in the early days, they would have thought that it was the strangest thing, but somehow I got tenure for all of it and got into trouble for all of it at the same time. At this particular point, I am really trying to figure out what it means to try to imagine another ten years of research, and you know, I'm not quite sure. Part of the impulse is to wrap up all of this stuff into some kind of book. Also, one of the things I was interested in was activating how drones function. We did a show about two years ago at Calit2, a year-long exhibition called "Drones At Home," and one idea I had was to develop the Palindrone which would chase Homeland Security drones on the border and sing to them. Like the words from Gloria Anzaldúa, and Nortec. Because we can imagine that the drone pilot sitting in Las Vegas might not know the culture, the voices and the history, and they might be bored; and so this might be one way. The Palindrone would be a singing drone that would exchange and share through multiple signals the life and experience, culturally and experimentally, of the border and border culture. [Theorist] Gloria Anzaldúa would be a core voice there.

The other area that I'm interested in is synthetic biology. It's kind of attached to this question of nano biotechnology, but synthetic biology has with it a protocol of creating completely new forms of biological life, which is both seductive in terms of a speculative fiction but at the same time (having read Frankenstein) it's rather horrifying. But I'm not quite sure how to enter into that particular space. The third area is immersive technologies like Oculus Rift and how that might be disturbed or dislocated—but again these are sort of tentative bases for consideration.

AES: The Palindrone project reminds me of the paper airplanes that the Zapatistas launched at the soldiers across enemy lines.

RD: Oh yeah, I think you're right. I think that it carries a pattern of how the work is done and that is using a platform to connect with the signal that exchanges messages, usually aesthetically driven messages. So yeah, I think there's a direct echo of the Zapatista Air Force involved and all of that, and you can see the same sort of thing, some sort of aesthetic reiteration.

AES: And I'm even thinking about your recent work with flight facilitation.

RD: Because of the Transborder Immigrant Tool, the question of borders has come to the fore, especially with the last few years of the Guatemala crisis and now the refugee and immigrant crisis in Europe because of the wars and climate change and what have you that's been building up for a while. Recently I had a flight facilitators' gathering and an open borders conference in Munich where we looked at the histories and valuation of flight facilitation which here on this border we call "coyote culture." So individuals who did flight facilitation from the GDR to Berlin during the Cold War are seen as heroines, yet at other times flight facilitation is seen as bad or illegal. In the crisis right now in Europe, everyday community members who put refugees in their cars to drive them from Hungary to the German border have been looked at as illegal and traitorous to the sort of nature of the EU. So the question that clearly manifests itself is about the figuration of the immigrant; the refugee is not really bound to the qualities of legal precedent and consideration and honoring of flight facilitation, but somehow a refugee and an immigrant are seen as outside of the normative values of a Euro-centric space.

![]()

Ricardo Dominguez and unknown U.S. Border Patrol (Mexico/U.S. border near Mexicali, 2007; un-staged photograph by Brett Stalbaum, co-founder of Electronic Disturbance Theater 1.0/2.0.)

AES: In Digital Zapatistas, Jill Lane questioned whether more people would find themselves criminalized as "illegal" aliens by those who guarded legitimate access to nation-states, and whether such maps would be reproduced in cyberspace. Do you think that the same kinds of questions you were thinking about with early net art and the Zapatistas are still just as important now?

RD: I feel that they are, in that the work has always dealt with the nature of borders. The internet allowed us to teleport across borders to route around, to go under, to go below or above what is a barrier; I see that kind of space as a potentiality but at the same time the consistent ontological cut of the border has been the reduction of bodies to wanted or unwanted labor, gendered femicide, and dreams of mass deportation, and again they tend to be consistent in the work in terms of the way it articulates itself.

One of the aspects of critical aesthetics asks if we can manifest alter networks, alter code, alter protocols, alter ways of discourse that will enable or disable the mimicking or the reification of borders in digital culture. I would say to a certain degree, with the rise of web 2.0, that hasn't been the case, but at the same time there has been a growth of do-it-yourself culture alter forms of infrastructures—other modalities of communication that I think continue that tradition—and that raises the question, can we re-organize the way these networks amplify borders and disallow them from doing that? I think that's still an important consideration. At times it might be about speed, and at times it might be about an inertia, and at times it might be about exiting, escaping that culture; or deleting it, or at other times it might be about leaks. Leakism is certainly a continuing manner in which we can de-stabilize the way governance is manifested, whether it was the Pentagon Papers or COINTELPRO up to WikiLeaks and Snowden. I think Leakism is another sort of alter protocol. I still tend to be an anti-anti-utopian in my sensibilities and I'm always happy about the victories great and small that we have as artists, and so until it's a bone that I'm not willing to let go of, yes, the way that Jill articulated it is still a core question.

![]()

Ricardo Dominguez, Critical Virus VI (performance as a member of Critical Art Ensemble, 1988)

AES: How many times have you been under investigation for your work?

RD: Well I get into trouble all the time. Another core interest of mine is performance, performance art and performativity. I always imagine and think of any gesture that I do as functioning within performance art. I feel that part of the aesthetic of performance art is liminality, and that performance pieces or gestures are about articulating a space that is somehow neither here nor there but somewhere in between. It’s transgressive—it tends to cross the boundaries of what is what might be socially acceptable, it carries with it a kind of personal risk often historically, and its traditional form right from Chris Burden being shot to Marina Abramovic whipping herself. The body in its simplest condition has been a core way of making things. The work that I've been involved in, whether its electronic new media or nanotechnology, has always had that sort of impulse at play. Because of these tendencies, I also get a great deal of trouble with institutions about the question of the body and its relationship to these issues. I guess that's to be expected if one is involved in performance and that certain questions will arise like "what is the necessity of this sort of work?" When you have painting, sculpture or video, you sort of have a clear articulation of frame, distance, control.

AES: What are some of the things that haven't been understood as performances?

![]()

Ricardo Dominguez, Mayan Technology (Root Festival, Hull, UK, 2000)

RD: Well Electronic Civil Disobedience is often seen as an activist work, but it's also a performance. For instance, when we did a performance for the NSA I wore my Zapatista mask and told stories about Mayan technology and they would ask, "Why are you doing that?" "What does that have to do with any of these things that we are worried about?" Well because at the core of all this is a performance, and performances bring questions about the body, about simulation, about the articulation of affect and the ephemerality of things and so that disturbs the way that people want to articulate what is occurring.

There is an old play called My Country Cousin about a Daniel Boone-like character who's invited by his big city cousins to Philadelphia. They all go to the theater, and halfway through the first act the Daniel Boone character runs on stage, hits the bad guys, and saves the Virgin. Everyone’s going, "Oh my god, you don't understand that this is a simulation—that is not a bad guy, that is not a virgin, this is a simulation!" So often the DoD, the NSA, my University, UCOP, Glenn Beck, and activists are sort of like the country cousin because they actually think that because they're seeing something, because they're feeling something, because something is occurring, that it is real; and I think that that's what performance art does. It is a real body, but again it's playing in liminal spaces and its transgressing those kinds of questions, so is it documentation or non-documentation? Is it real or is it Memorex? Is it simulation or is it non-simulation? As Rancière says, "The Real must be fictionalized in order to be thought." The histories of performance art are around the trickster, the shaman, la bruja, ritual, magic, all of those things come into play. So often power gets angry. They want to situate it, to articulate it—but at the end they are the country cousin and they think because they see it, because they feel it, because it articulates itself within the realm of the real that it is real, but they haven't taken the pill.

AES: What’s the pill? Are you working on it inside your laboratory?

RD: (Laughs)

![]()

UCSD and UCOP (University of California Office of the President) attempted to de-tenure Dominguez for doing a VR Sit-in on the UCOP website in support of the statewide protest by California students against the fee hikes in 2011, and also for creating the Transborder Immigrant Tool. UCSD students, faculty, and others supported Dominguez with a march as he walked to meet UCSD campus authorities investigating these gestures (2010).

Ash Eliza Smith is a multimedia artist and writer. She has produced work exploring ficto-criticism, technology and the body for Vice, Motherboard and the Creator’s Project and curated and written for the New Media Caucus and Media-N journal. Smith has collaborated with the Arthur C. Clarke Center for Human Imagination to curate large-scale science fiction and speculative design events, Edgeland Futurism and ARE WE ALONE ARE WE ALIEN?, which have received awards from the UC Institute for the Research in the Arts. Smith is the current Director for Art and Technology in the Culture, Art, and Technology Program at the University of California of San Diego.

Notes

1. This theoretical framework is set out in Critical Art Ensemble's 1994 book The Electronic Disturbance. Dominguez later wrote, "For Critical Art Ensemble, it was clear that cyberspace, as it was called then, was the next stage of struggle. The activist reply to this change was to teleport the system of trespass and blockage that was historically anchored to civil disobedience to this new phase of economic flows in the age of networks."

2. Hauntings (1997), by Dominguez, Francesca da Rimini, and Michael Grimm, is an example of HTML conceptualism, an artistic gesture originally made for users with a browser and a dialup connection.

3. The "virtual sit-in" is a form of activism in which protestors occupy a website with the intention of slowing it down.

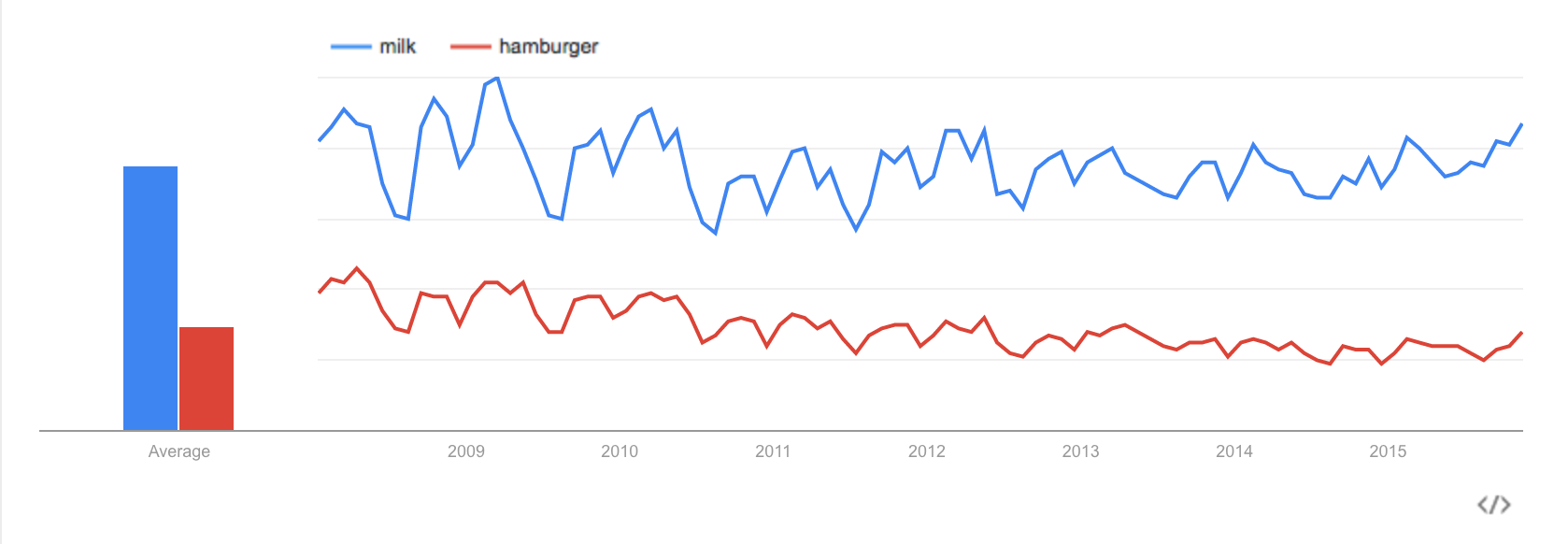

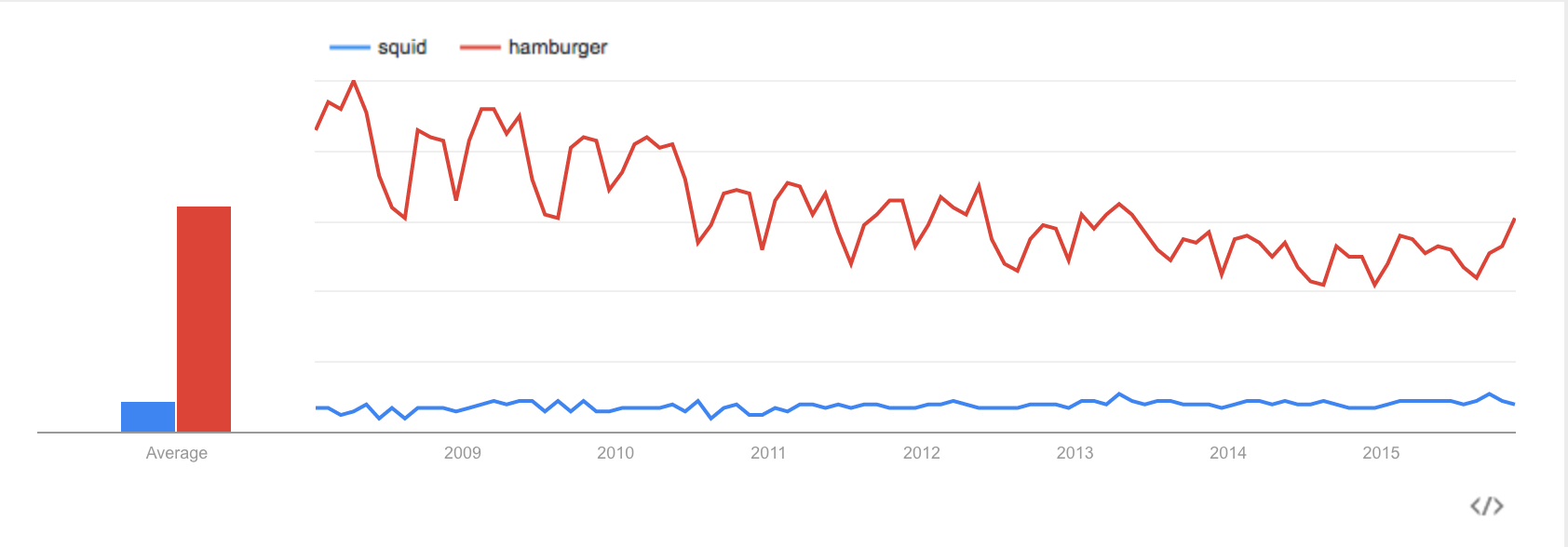

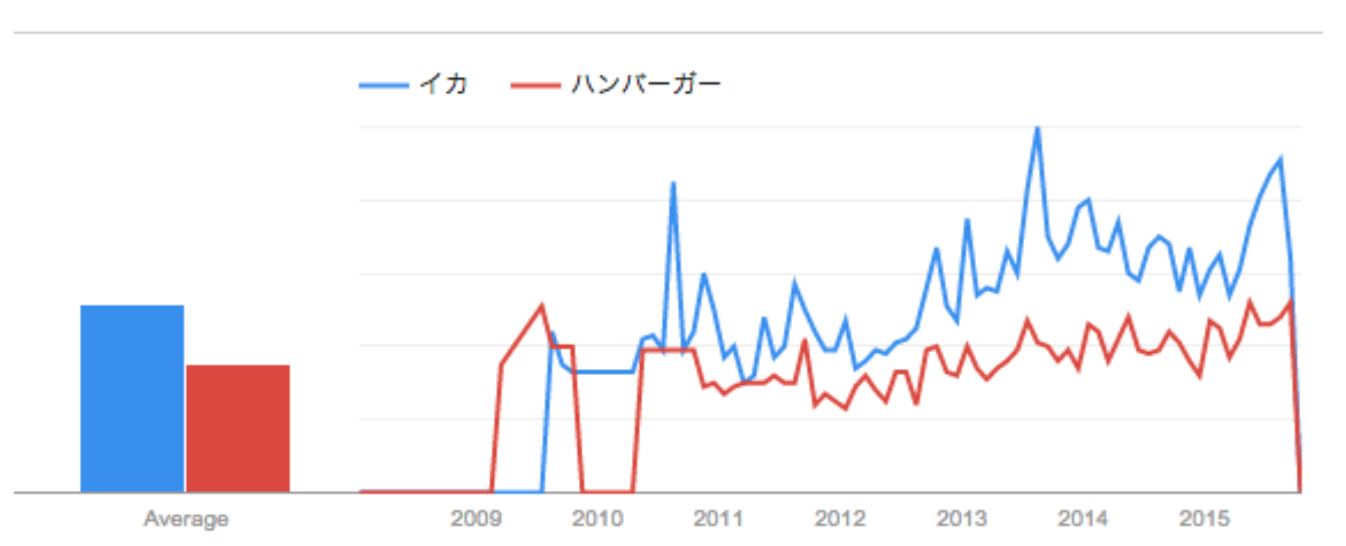

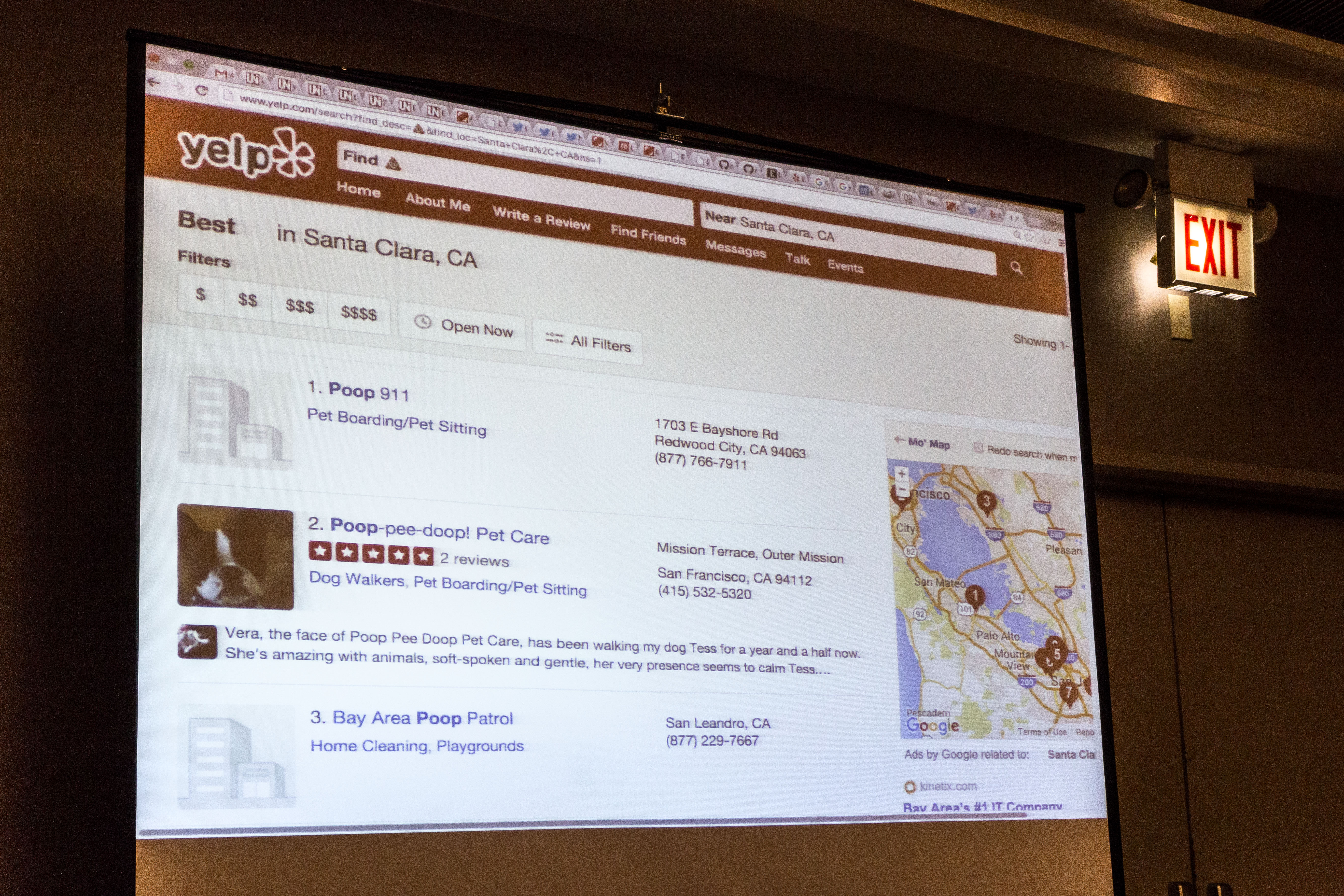

pulls up different results than #

pulls up different results than # . The result? A racially segregated Instagram.

. The result? A racially segregated Instagram.

_large.jpeg)