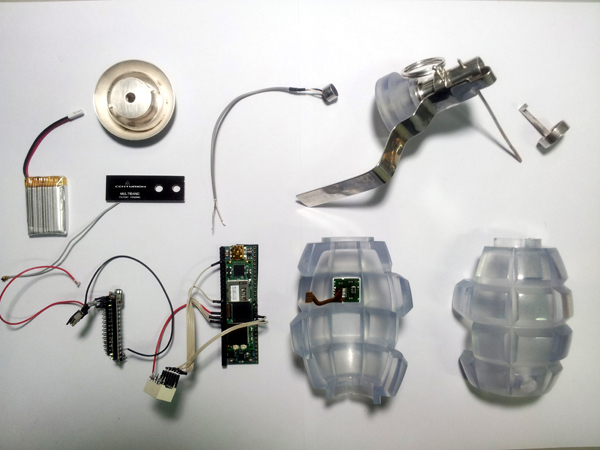

Cecile B. Evans, You May Keep One of Your Children (2011)

Many of your works reference and seem to be derived from popular culture icons, from Paula Abdul and Meryl Streep to Jean-Luc Goddard and J.D. Salinger. What is the role of popular culture in your work? Do your works attempt to comment on our conceptions of these cultural references or are they simply a point of departure?

One thing that is important to me in the work I’m doing now is to get to where several points of reference can exist on the same plane, with equal weight. In this world, Paula Abdul goes with Pina Bausch, Meryl Streep with medical instruments, and an array of other elements in each piece that vary in their visibility. I’m interested in reaching a place where the high blends into the low, the earnest into satire (and vice versa) and making a complex constellation of elements that winds up as something that’s really simple aesthetically. As I write this, I’m gluing nail art rhinestones to spell out a quote from Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolf? in Braille to spill from the tear ducts of a vintage photo a friend emailed me of her parents kissing. I’m simultaneously editing a video that features a semphore version of Whitney Houston’s I Have Nothing on sleeping pills that unfolds while a Lucinda Childs-like ghost floats around dying golden embers. At the moment, we exist in a culture that lets me use these very different values to refer to the same emotions. It’s as though we’ve entered a 2nd wave of New Sentimentality where it’s as appropriate to relate loss to an Aaliyah song as it is to do so with Barthes’ Mourning Diary, and either can be done sincerely or ironically… at least I’ve always equated things that way.

I enjoy using broad references in popular culture as a reflection on how different industries have created universal conduits.

Your past works seem to levitate around notions of intimacy and relationships. Some of your projects imply that intimacy doesn't necessarily require physical closeness and can be instead experienced through connections made in internet or other forms of technology. Yet, in the age of tweeting and texting, social networking creates this constant yet increasingly vapid communication between people that feels anything but intimate. How do you think recent technology affects our perceptions of intimacy? Do you think physical closeness can be replicated within a technological frame, or do these new forms of connecting force us to reevaluate what we deem “intimate”?

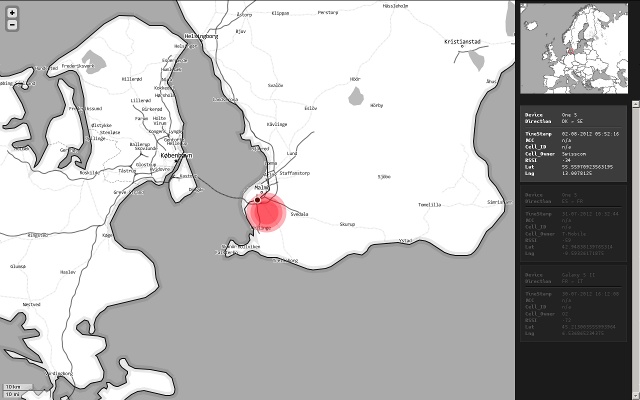

In the past I’ve been interested in the internet as an intimacy generator, using its content as source material, without judgement. One thing that I’ve found since I’ve started is how blurred the lines between the virtual and real have become, to the point where it isn’t a big deal. There are feed relationships that can cross over to a more direct form of contact, either as an extension of what you’ve created or used as supplements to wish fulfillment- from rejection to validation. The volume of people and easy access serves as a lubricant either way

The danger isn’t with ourselves- I don’t think those of us who have the filter to realize what’s ok and what isn’t will lose that. It’s more how flippantly we display our feelings. The faith in an emotional utopia was decried in 1994 by Carmen Hermasillo (aka humdog) who warned that the spilling of our guts on the internet would result in the commodification of our feelings by large corporations. That’s happening now. I fear that the companies are mirroring back what we unknowingly feed them in ways that will reevaluate the meaning of intimacy for us.

But one thing has been clear from the beginning, you can have real things happen to you virtually. I think that forming a relationship of any kind online is totally legit.

You investigations span various mediums, from sculpture to performance and video in several. You also seem to gravitate towards collaboration, especially in your most recent video Straight Up, where Mati Gavriel provided the music and Edmund Brown added the after effect. In your process, what variables do you take into consideration when assigning an appropriate approach to a new project? Is the decision to use a specific medium or to include a collaboration demanded by a new project, or does it facilitate in the formation of the final piece?

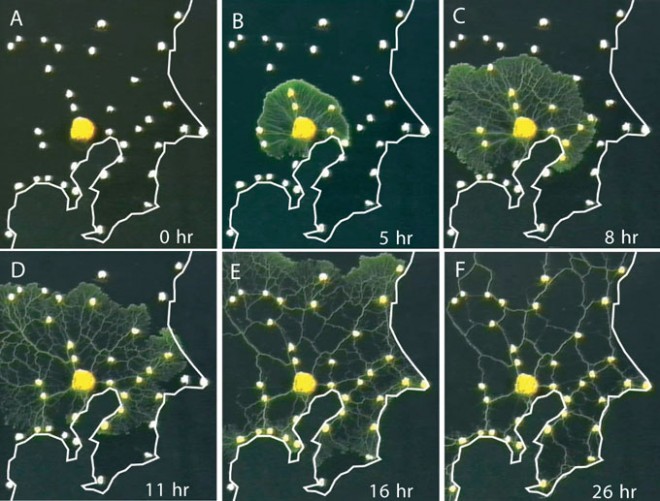

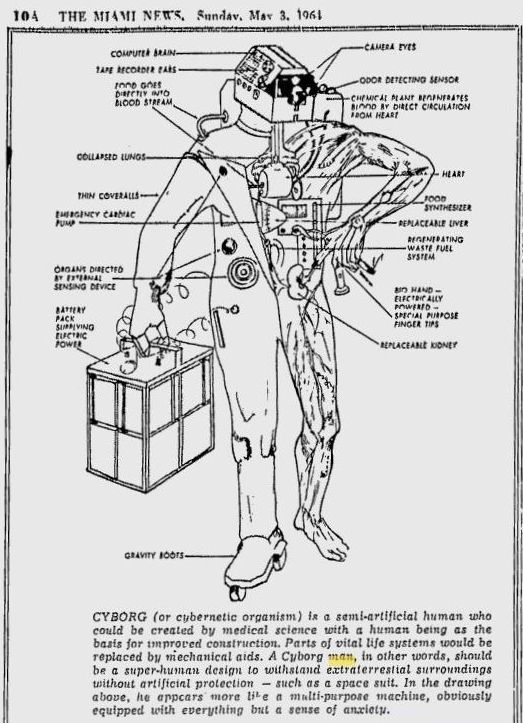

I like to work with experts, people who are very good at doing something that I can’t. Mati is a professional pop songwriter- we’ve done 3 scores together. I’ve also collaborated with forensic scientists and neurologists- each one becomes analogous to a cyborg apparatus that enhances the piece and informs me. They transmit my fantasy into something that’s technically possible and it’s important to recognize that value. Basically, I don’t think the piece should be limited by what I can’t do.=

Congratulations on receiving Edmash Award. What can we expect from the upcoming audio guide you will be creating for the Frieze Art Fair?

Thanks! At the moment I’m focused on organizing a group of non-art people that will serve as a panel that responds subjectively to a selection of artworks in Frieze. I’m hoping to create an experience that introduces an emotional language into the art fair, dominated by material and intellectual value and use the audio guide to generate a power shift. I’m also playing with a physical element in the form of a telepresent host that will speak directly to the visitor, to further break up the dynamic and make a dialogue within the subjective realities.

Age:

29

Location:

Based in Berlin, on residence in London.

How long have you been working creatively with technology? How did you start?

From the start. My first experiments were lo-fi videos I shot on an HDV cam edited together with AT&T text to speech narrators.

Describe your experience with the tools you use. How did you start using them?

My most important tool is the mood board. Nearly every piece I make, no matter the medium, gets a mood board. I find images or video for every part of the idea and then summarize it in 3-5 sentences. It all goes on a PDF with hyperlinks. From there I know if the concepts in the piece will work visually, if it’s missing something or there’s too much.

I shoot on the Canon 5D/7D Mark 2, which doesn’t handle movement very well and helps me avoid erroneous zoom and pan ideas. I use Final Cut, because even if I learned another program my fingers would still Command + I + O + C. I use the phone, calling to get things done is underrated. Everything and everyone else is found via the internet. All of my projects, and the development of my work, begin with a google search.

Where did you go to school? What did you study?

I went to NYU, where I trained as an actor, first in Meisner (method acting) then in experimental theatre. That encompasses a lot- things from Balinese masks to postmodern dance. I’d say one of the most important introductions to an artwork I had was in choreographer Annie B. Parson’s class- she showed us The Way Things Go as inspiration for a cause and effect based choreography assignment.

What traditional media do you use, if any? Do you think your work with traditional media relates to your work with technology?

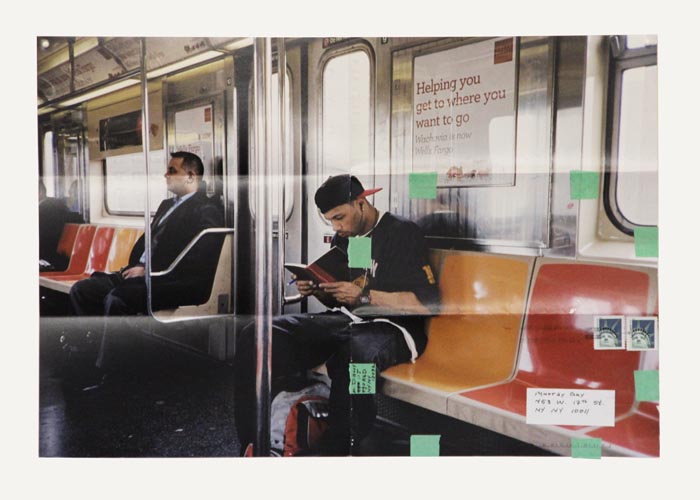

I also work with collage and sculpture. I find out how to make most of the visual components online- for example the mixture I used to make the tears in Crying About Crying About is taken from an archived forum post on how to make condensation for camera.

Are you involved in other creative or social activities (i.e. music, writing, activism, community organizing)?

I like to make dinners for groups of people.

What do you do for a living or what occupations have you held previously? Do you think this work relates to your art practice in a significant way?

I’m an artist for a living now which feels great, I’ve been making work for 3 years. Before that I was an actress, which I started claiming at age 5. I’ve played people like Phaedre, a mentally disabled preteen, and a newspaper covered narrator who told the history of the potato.

I realized that the process of building a character or narrative to house emotions wasn’t right for me and that I was more engaged by the generation of emotion and how contemporary culture values it. My artistic practice suits those needs.

I’ve also been a makeup artist at Barney’s, Bloomingdales’, and Bergdorf, as well as a bartender, cocktail waitress, and secret food critic. But those don’t really relate to my work.

Who are your key artistic influences?

I look at a whole lot of work, all the time, from historical artists to my peers and am regularly informed by parts of them. Bas Jan Adler is a big one. But mostly, I’m influenced by work from outside of the art world- I borrow a lot from movies, especially sci-fi fantasy. Also choreographers like Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker, tv developers like Jim Henson, Beyonce videos, anthropologists like Malinowski- sorry to be so inarticulate but there are a lot!

I think it’s nice to mention the artists who’ve influenced your work through their generosity. There have been friends who were casually very influential simply by taking my desire to work seriously, even before I was working professionally. Artists like Jordan Wolfson- who lent me his apartment (my first studio) and books for well over a year after he left Berlin, or writers like Victoria Camblin and Francesca Gavin who have written excellent texts for shows that weren’t real shows, or done a piece with me at a time where I needed a push to contextualize my own work. I don’t think that this happens enough between peers and it’s vital. Reminds me of stories you hear of people like Sol Lewitt, who encouraged a lot of less experienced artists in his time. There should be more of that!

Have you collaborated with anyone in the art community on a project? With whom, and on what?

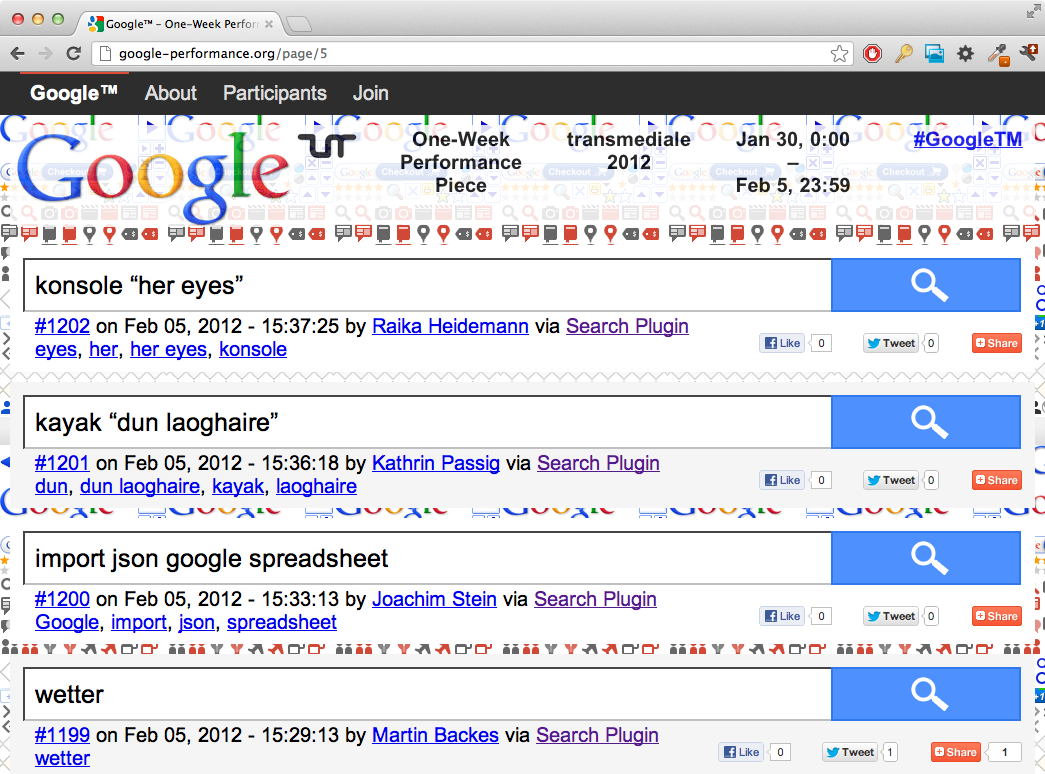

I’ve collaborated several times with curator Rebecca Lamarche Vadel. Together we did Art By Telephone, a series of performances where we realized artist’s works under their instruction via Skype. I also did a performance in which I explained an exhibition she had curated via the magic of Power Point and a series of subjective google searches.

Do you actively study art history?

I worked really hard at this when I moved to Berlin from Paris (where I was still an actress). I tried to see and read as much as I could, I didn’t do anything else for months, which was easy as it was the dead of winter. My knowledge is embarrassingly contemporary though. I’m still constantly looking at things and filling in blanks. But I didn’t go to art school. I get super excited when I see something that I’ve only seen in research- yesterday I saw Hans Haacke’s Condensation Cube at the Tate and practically took a lap around the room.

Do you read art criticism, philosophy, or critical theory? If so, which authors inspire you?

There are a few works that I consistently return to- John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, Clement Greenberg’s later essays, Artaud’s No More Masterpieces, the Oulipac writers, Malinowski’s The Sexual Lives of Savages (but mainly for the photo captions!). I like reading what my friends are writing, I think they are quite good.

Are there any issues around the production of, or the display/exhibition of new media art that you are concerned about?

I think that things are progressing in an exciting way, with all of the questions and concerns. How will things be archived, how will digital forms be preserved, the relationship between digital and physical, etc- I think these questions are being asked and experimented with.

One thing that I’m quite taken by is a shift in authority that’s happening, supported by new media art. Because of the internet, people have visual access to things they don’t have physical access to. Often they are receiving someone else’s perception of the work, which then gets added to their own- possibly very far from the artist or curator’s original intention. I don’t think this is always a bad thing and will ultimately encourage the viewer to approach art more freely. It’s akin to something ancient- the tradition of oral history- and brings a touch of magic back into the equation.