As an artist, my interface with holography and laser technology is always aimed at achieving a particular art piece that communicates the concerns of all my work. They are chance, change, it-ness, attention, a concern with perception.

-Peter Van Riper, From “On Holography” (1980)[1]

![]()

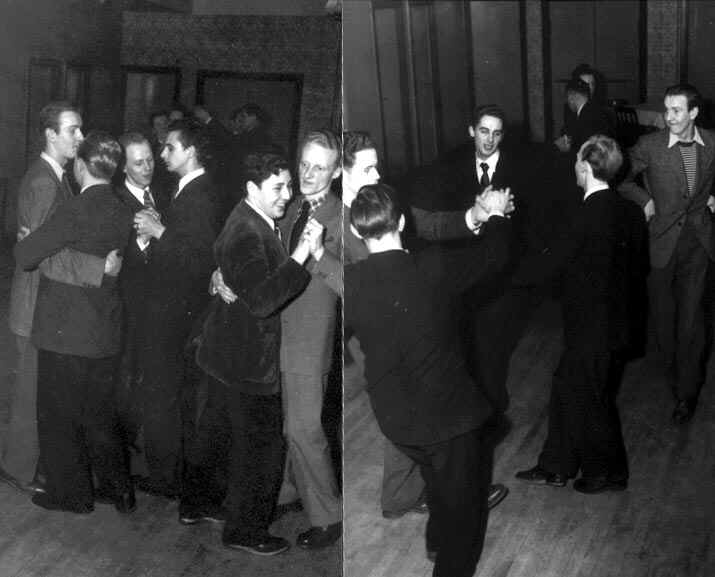

Peter Van Riper, Room Space I (1976-78)

In the summer of 2012, Rhizome’s partner institution, the New Museum, hosted “Pictures from the Moon” in its Lobby Gallery, an exhibition of artists’ holograms from the late 1960s to 2008. The size of the gallery necessitated a tight focus on artists who were not “holographers,” but rather produced holograms which function as novel outliers in their practices (Bruce Nauman, Louise Bourgeois and James Turrell among them). As critic Martha Schwendener noted in her New York Times review of the exhibition,[2] a broader survey of holographic art could have revisited the work of artist/tinkerers like Rudie Burkhout, Margaret Benyon and Lloyd Cross, all of whom were more actively on the ground, pioneering holograms and laser-based arts as a distinct form of visual art.[3]

In between these poles—the artist who dabbled in holograms and the card-carrying holographer—hovers the work of the artist Peter Van Riper. Van Riper (1942-1998) split his time between the world of holography and the music and performance avant-gardes that had emerged in the wake of Fluxus and the innovations of composer John Cage. Because of the in-betweenness of his practice, and because all of his projects are best understood not on formal terms but in the context of broader concerns with human subjectivity and perception, Van Riper’s work has perhaps not yet received the full recognition he deserves within either field.

![]()

Peter Van Riper, School of Holography print (circa 1971).

Peter Van Riper, Holopane 2 (circa 1970s). Van Riper picking up the pieces of a broken hologram. Filmed by Joseph Bogdanovich.

Although he created some of the earliest pieces of holographic art, shown frequently at the Museum of Holography in SoHo, and taught holography at CalArts and the School of Holography in San Francisco, Van Riper is best remembered today not for his work in this new medium, but rather for his performance collaborations with Simone Forti (with whom he was married from 1975 to 1986) and his avant-garde music for saxophone and various custom-made instruments such as found aluminum baseball bats.

![]()

Peter Van Riper circa 1983. Photograph by Eugenia Balcells.

![]()

Mailer for PS1 show with Simone Forti that featured graphics and holography (1975).

![]()

Van Riper playing saxophone with Simone Forti in the MoMA Sculpture Garden (1978).

While much of this musical/performance work was meant to be beautiful, it was also meant to point away from itself and instead activate the listener’s/performance viewer’s awareness of their immediate space. That is, in lieu of carrying one away from reality, as is often one of music’s more romantic goals, Van Riper sought to locate the listener in the here and now, accentuating the experience of being present in the world. A representative work is Doppler Piece (1979), in which he used his saxophone and carefully placed microphones to explore the Doppler Effect (changes in pitch as the source of a sound moves toward and away from an observer). The objective here was to experiment with effects in sound but also to reorient the viewer’s attention to the world around their bodies.

Van Riper described his intentions with music by saying, “I hope to offer something fresh as music as well as attention: attention to light and sound, to seeing and hearing in art and music.”[4]

Although works such as Doppler Piece are formally quite different from high-tech holograms, they encourage very similar modes of awareness. In perhaps the most pointed example, Room Space (1976-78), a 360-degree hologram depicting the artist’s body in an empty room directs the viewer’s attention away from the spectacle of technological gadgetry and toward the room in which the hologram is installed: the light, the architecture and the location of one’s body in space.

![]()

Peter Van Riper, Room Space II (1976-78).

Van Riper played reverberating gong music in the Room Space installation to complement the hologram. In regard to the project, he wrote:

The music for the installation has standing waves that fill the space with shimmering sound. A metal Buddhist gong produces continuous sound so that a sound wave “stands” in the space.

Light is a wave

Sound is a wave

The images are about light and seeing, as the music is about sound and hearing. The holograms are about awareness of space.[5]

![]()

Cover for Room Space, album of music composed for the installation (1978).

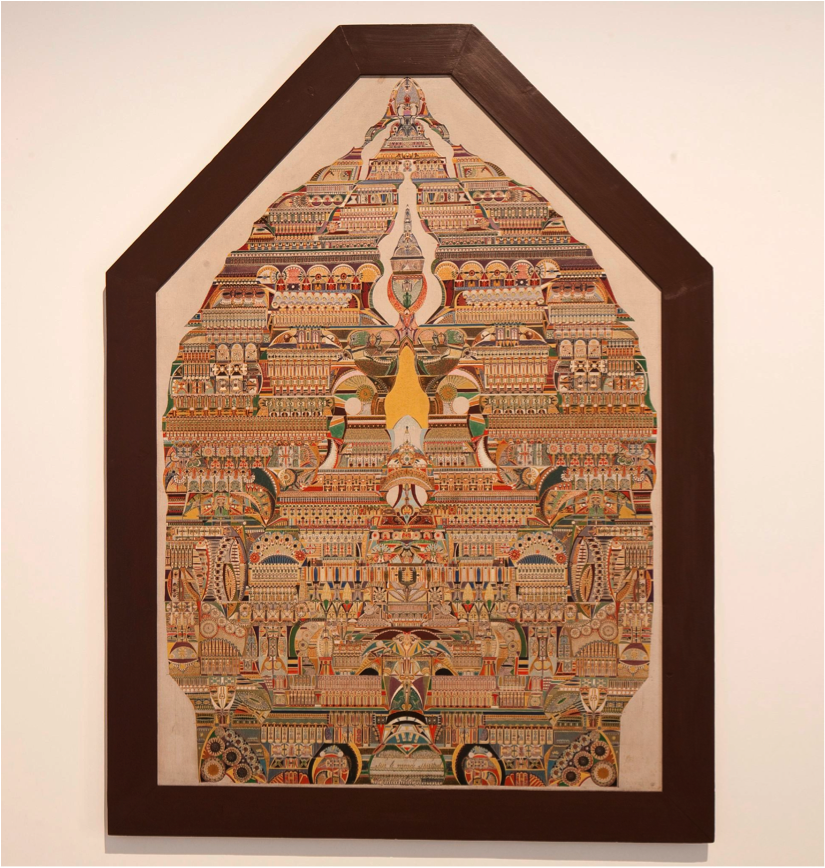

Born in Detroit in 1942, Van Riper received a BA in Eastern history and Art History from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and studied Eastern philosophy and art history at Tokyo University in Japan. Upon returning to the United States in the early 1960s, he met the laser physicist Lloyd Cross and realized that the way holograms interpreted light overlapped with his Zen Buddhist-inspired aesthetic interests. Together he and Cross quickly built a small hologram company, Editions Inc., created some of the first holograms-as-artworks, and organized what may have been the first holographic art exhibition—Sound, Light, and Air (1968)—at the Cranbrook Art Museum in Ann Arbor, Michigan. As holograms are notoriously difficult to photographically document, most of what is included in the documentation of the exhibition below represents the inflatable sculptures, which were the “air” component of “Sound, Light, and Air.” But there are shorter sections (such as 1:30-1:49) where the lights are dimmed to demonstrate the 3D effect of the holograms dancing in space along, with the set-up of green laser lights and glass plates used to create the effect.

In Room Space, Van Riper sought to spur an awareness of the viewer’s subjective sense of space. The hologram exhibited in Ann Arbor, though, has a more phenomenological aspect, visualizing for the viewer the otherwise imperceptible waveform structure of light. This is also true of two later works, Rainbow Man and Rainbow Mandala (both 1974), in which colorful holographic plates interacted with, respectively, sunlight from a window and symmetrical laser lights to create bright, psychedelic patterns. The patterns are mesmerizing, but for Van Riper, the ultimate goal was always to expand viewers’ awareness of what is occurring around their bodies.

![]()

Peter Van Riper, Screenprint based on Rainbow Man (1974).

![]()

Peter Van Riper, Plant in Laser Light (1982), from Laser Light Photographs.

![]()

Peter Van Riper. Aloe Vera in Laser Light (c. 1983). Silkscreen.

In a text on photographs made with laser light diffractions,[6] Van Riper refers to John Cage’s notion that it is the job of art to address man’s orientation to nature. Van Riper’s focus on this goal led him to experiment in whatever mode was available to him, from the saxophone, to homemade instruments, to holograms, to paintings. Because of this, he found himself untethered to a particular movement or school and, thus, difficult to place in the art historical canon. But it’s also what makes him such a fascinating artist to explore.

At the end of his all-too-brief life, Van Riper was able to merge many of his interests—avant-garde music, laser-based imaging, and a more recent use of computer software—in a series of gestural works. The Laser Sound Scans, as he called them, were musical compositions translated to laser pulses and recorded on a rear projection screen by a digital camera. Although simple, they are among the most beautiful pieces he produced.

![]()

Laser Sound Scan 14 (1998). Digital print.

![]()

Laser Sound Scan 6 (1998). Digital print.

![]()

Laser Sound Scan 17 (1998). Digital print.

“It’s fantastic,” he wrote of producing these works. “It’s like being lost in the mountains or something, there are so many light waves. They are not images that I thought up and made drawings of, they’re really the recordings of the light, the way the light behaves. This experience is research about something mysterious in nature.”[7]

Imparting this feeling of a mysterious vitality in light or an empty room, and asking viewers and listeners to pay attention to their subjective experience thereof; this was Van Riper’s art, and he pursued it across a lifetime through holograms, saxophones, baseball bats and anything in-between.

For more information on the work of Peter Van Riper see petervanriper.tumblr.com

Special thanks to Dina Helal for her help in preparing this article.

References:

[1] Essay included in Berner, Jeff. The Holography Book. New York: Avon Books, 1980.

[3] For more information on this scene see, e.g., Kallard, Thomas. Laser Art and Optical Transforms. New York: Optosonic Press, 1979.

[4] From a previously unpublished text by Van Riper on his work Cups (1993).

[5] From “On Holography” in Berner, Jeff. The Holography Book. New York: Avon Books, 1980.

.jpg)

.jpg)