The following conversation was re-published with permission from the brand-new publication Spheres by Swiss graphic designer Philippe Karrer. Rafaël Rozendaal and Jürg Lehni discuss their shared interest in vector graphics, which are based on mathematically-defined geometrical entities such as lines, circles, and points, in contrast with more commonly used bitmap graphics, in which values are assigned to grids of pixels.

![]()

Rafaël Rozendaal: Vectors are based on mathematical equations. The equations are perfect. No matter how we try, we can never render a perfect circle in any medium. And even if we did, our imperfect eyes would not be able to register its perfection. Do we have to accept that such shapes can only exist in our mind?

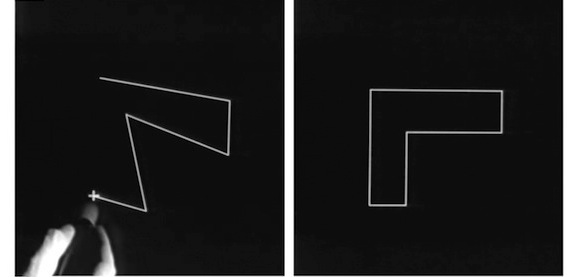

Jürg Lehni: What a start of a conversation! This distinction between the abstract mathematical formulation of geometric shapes, and their realization into concrete, physical forms is pretty much at the core of my fascination (or shall I say obsession?) with vector graphics. The shift is always there, whether it is illuminated pixels being turned on or off, a mark-making tool being moved by motors, or a laser beam being guided by electronically-moved mirrors, burning a line permanently into a physical surface. What it boils down to is the difference between the abstract idea behind something on one hand, and its concrete form when it becomes reality. Plato’s theory of forms comes to mind, with its ideal or archetypal forms that stand behind and define the concrete, physical things.

What’s funny about the example you mention is that vector graphics and bezier curves are actually not even able to describe a circle perfectly. Four cubic bezier curves can be used to approximate a circle pretty accurately, but mathematically this is not a perfect circle either. It is close enough for most human purposes, though.

RR: Have you ever tried to explain what vectors are to your mother?

JL: Not really! I have tried to explain vector graphics and the mathematics behind bezier curves to graphic design students though on multiple occasions, when teaching scripting workshops based on Scriptographer and Paper.js, together with Jonathan Puckey. What I like about that is that the students often already have an intuitive understanding of the nature of such curves, since they are used to working with them by hand in graphic design softwares such as Adobe Illustrator. They know how to use the tangential control points to manipulate the velocity, tension and curvature to achieve the desired curves. I think they are able feel the mathematical nature of these curves.

But since you asked, did you ever explain vectors to your mother?

RR: No, I never tried. I think it’s something that is hard to explain to someone who doesn’t really use computers to make images.

JL: I wonder how you ended up more or less limiting yourself to this format. Was there first a fascination with the idea of pure form and its abstract mathematical representation, or was it more a question of what tools were available at the time?

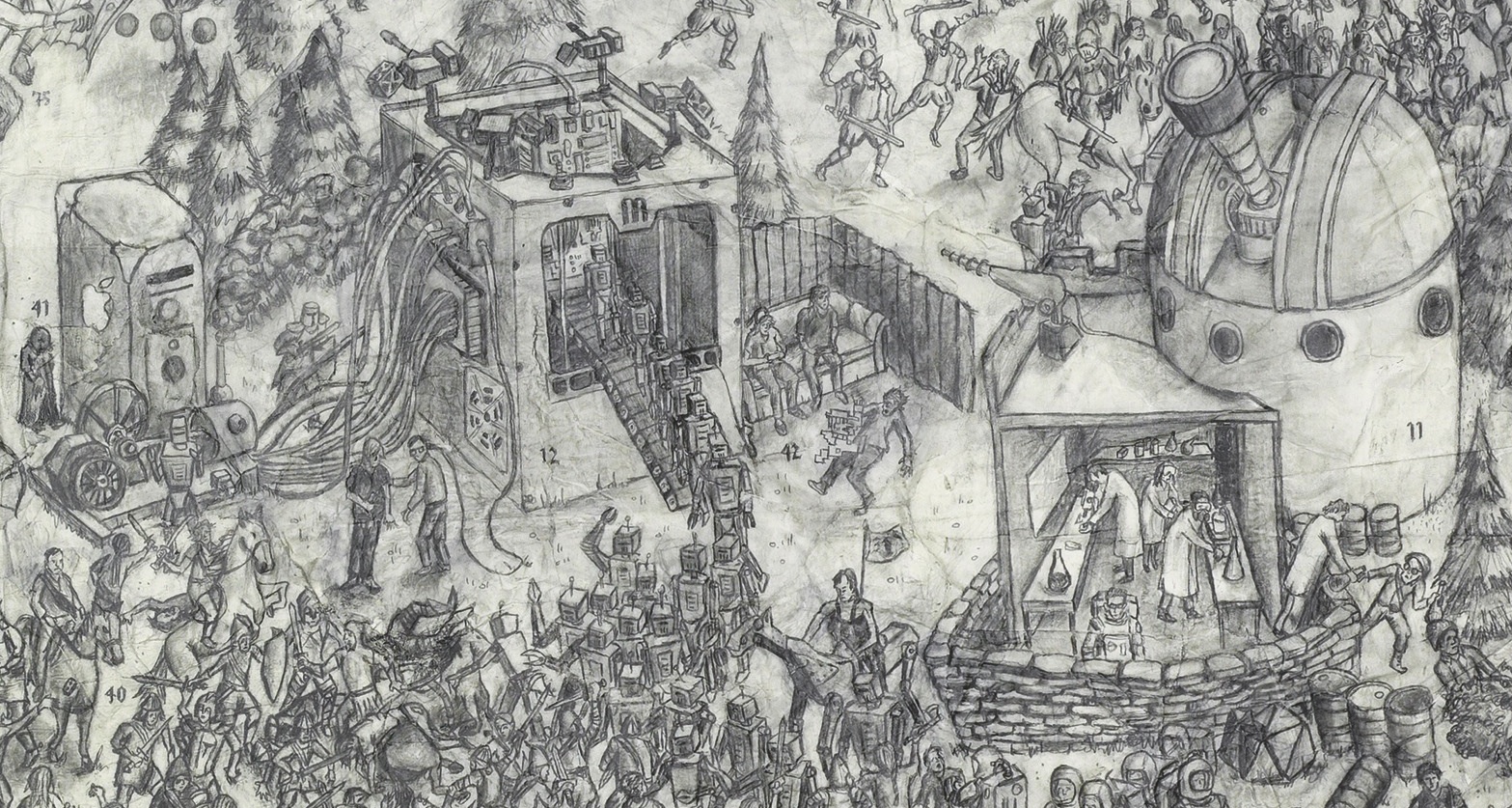

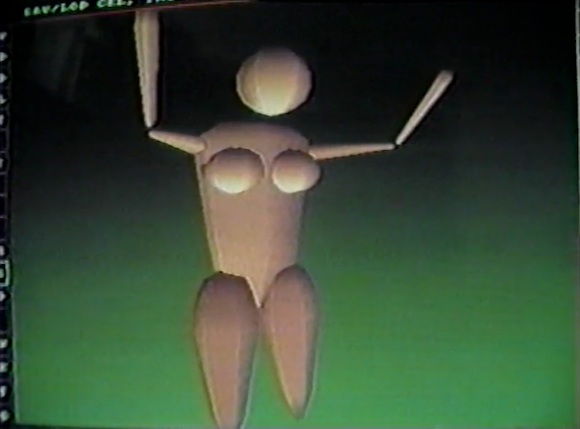

RR: As long as I can remember, I’ve been drawing. I enjoy converting thoughts into lines. I have an affinity for "abstraction in service of reproduction." What I mean is that in order to make images that are easily copied/transmitted, artists have invented different ways of simplifying. Think of Egyptian reliefs, Japanese woodblock prints, early Mickey Mouse, early video games. In all these cases the medium forced artists to simplify. Vectors are honest about the fact that they are computer imagery. It is clear that they are made on a computer, they’re not trying to be real. I would describe my work as "lossless image compression by making human decisions." I don’t let a digital camera decide how to compress an image, it is my choice how I convert thoughts and perceptions and feelings into lines. Isn’t lossless a beautiful idea?

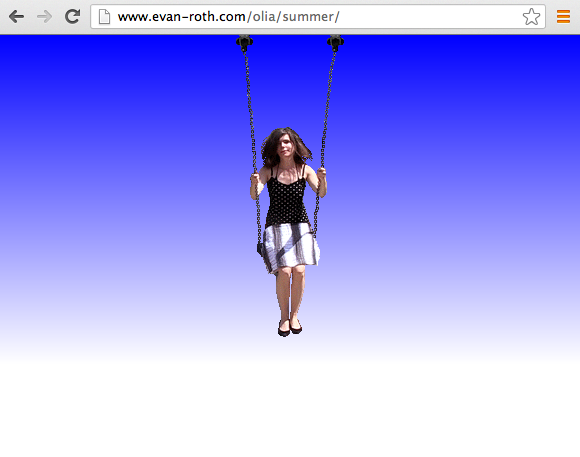

![]()

I always felt that using a computer, we should not try to depict the world in ways that were possible before, like photography and video. We should find new ways of depicting. I always felt like pixels are an approximation of reality, and vectors are a reconstruction. It is the job of artists to reverse engineer reality into their medium of choice. I chose the computer screen as my medium because I like that these screens are everywhere. Vectors felt like the best solution for bringing impressions from “the real world” to the screen. I’m trying very hard to explain why I think it is better. I just feel like bitmaps and Photoshop filters and pixel displacements and mpeg compressions are trying to be something they are not. But that doesn’t really make sense, you can use them in a way that is truthful. But when I see textures in 3D renderings I just feel like they are trying to be something they are not. Does that make any sense?

Vectors do have their limitations. It is really difficult to make something look dirty. Everything always looks clean.

JL: While I never was good at drawing, I can totally relate to this interest in the limitations enforced by the technique/technology of choice. A lot of my work deals with that and attempts to make it visible. Computer companies like to pretend that there are boundless possibilities, that our softwares do not dictate the way we work, that our devices are magical and always there for us. As an attempt to change the role of technology in our lives, and our relationship to it, talking of limitations and celebrating them seemed like an important step.

The observed lack of dirt in vector graphics was also what motivated me to start making drawing machines that would convey the abstract information behind these drawings in imprecise, sometimes clumsy, almost human ways. A machine that struggles with gravity is more approachable than one that impresses with seemingly endless precision, and when working with such a machine, one has to draw for it, with these limitations in mind. My biggest beef with

Macromedia Flash was that everything looked so clean, and sort of cheap at the same time. It was almost like a graphic designer who would print everything with a color laser printer on glossy paper.

![]()

RR: Did you find Flash rendering vectors noticeably different from other vector software?

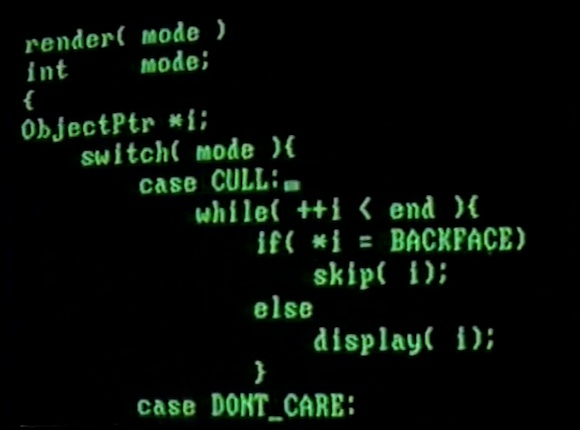

JL: Flash as a piece of software has a very interesting history. It was originally called FutureSplash Animator, and was released by FutureWave Software in 1996. The company found a really interesting way of dealing with vector graphics that was very different to what we are used to from Adobe’s prevailing PostScript model, which is what most other applications and standards are using. Since the file format was designed for vector graphics animations on the web, it had to be rendered as fast as possible, and consume as little memory as possible when stored.

Their solution was to use only quadratic curves rather than the cubic bezier curves that we know for example from Adobe Illustrator. These are mathematically less complex and easier to render. And instead of having these curves describe shapes that are to be filled and/or stroked with colors, they decided that each curve (not shape) can describe a stroke, a fill color to its "left" and one to its "right." It is hard to explain what this meant mathematically, but I am sure you know how this felt like when working with these curves in the application, as they found a really clever way to embed this into the user interface: you could treat vector graphics almost like pixels, fill any interior shape, cut through existing drawings with a simple line or curve, and move segments that were divided this way around independently. If you did not want this to happen, you could move things to a different layer, or group them.

All these technical differences behind

the scenes also means that the way these curves are rendered differs quite a bit from other approaches. I am not quite sure why, but I believe it is due to speed optimizations that were introduced in these early days, that Flash’s antialiasing never looked quite as good as it should have. There was weird rounding going on, coordinates were not stored as floating point numbers, but the less precise fixed point arithmetics were used, which seemed like a good way of optimizing things back then, but nowadays makes little difference and leads to imprecision.

Also, the initially really creative and powerful concept behind these curves unfortunately then got watered down through a series of acquisitions, first by Macromedia, and later by Adobe. Now it’s just a mess of many different models that are layered, like any software that Adobe acquired and merged into their Creative Suite.

![]()

JL: When you started working with Flash, were you attracted by this aesthetic? I think you have found a really good way to master it while avoiding all the pitfalls that come with the territory.

RR: What is interesting is that most people need a level of irony or nostalgia to appreciate the beauty of something. It has to go through a number of years where something becomes safer. Think of early video games, it took 20 to 30 years for those images to be appropriated/used in art. Perhaps it’s the same with Flash, in 30 years Flash movies will have the same nostalgia (and warmth) as VHS tapes do now.

I chose Flash because it was the best tool for me. The choice was quite practical. small files, reliable, cross platform... Other options like JPEGs, Quicktimes, Shockwave, Java applets, were all bitmap based and did not scale well. Browser windows are never fixed size. I see the entire web page as my canvas, not part of it. So I needed an image format that can adapt to the wishes of the user.

RR: Is antialiasing a more truthful rendering of a vector shape on a pixel screen, or is it a lie?

JL: I can see how you could think of it as a lie, because it is using different shades of a color at the border of a shape to trick the eye into thinking there is more definition to the image. But at the same time, if you would print the shape at really high resolution on a paper, and then take a digital photograph of the printout at lower resolution, you would get very similar "blurred" borders. In that sense, I would call antialiasing (and even more so, subpixel rendering) a very convincing trick. One can also argue that any rendering of such pure information into a grid will be a lie, since it will be imprecise. An antialiased version of the same shape would then just be a more convincing lie. In that logic, I can see how an aliased version is then so obviously a "lie" that it is more approachable, likable.

JL: This might be a rhetorical question, but which aesthetic do you prefer? Did you ever experiment with pixelized styles and aliased graphics? Do you see a risk of things looking nostalgic when going down that route?

RR: Yes, I felt like antialiased vectors are closer to what the vectors are. Ed Halter wrote that pixelated graphics are a form of "digital materialism," they acknowledge that there are physical building blocks. But now those pixels are becoming so small that to show pixel art you have to use 4 or 9 or 16 pixels to show 1 pixel of a pixelated image. We are moving to post-pixel displays.

JL: I agree. Eventually, the two will become the same, and the artifacts will disappear. I feel the same about any kind of digital artifact, be it the blotchy JPEG compression, its animated twin with MPEGs, or the phonetic qualities of badly compressed MP3s. One could argue that’s the cathode ray tubes and the VHS of our times. The younger generation probably will hold similar nostalgic feelings for them once they are replaced with a new reality that is so intensely digital that it will overwhelm us with its perfection.

JL: Are you looking forward to this moment where all these artifacts eventually will disappear? A sort of singularity where all media merge into one and become indistinguishable? The lack of any kind of artifact as the final artifact?

RR: I think the future is very uncertain. That is exciting and scary at the same time. I imagine at some point the idea of a display will be old. Why do we need displays? We will just inject ideas into our brains. Maybe we won’t even need ideas, we’ll just inject feelings…

![]()

RR: Do you find your audience to be mostly geeks?

JL: I hope not! I am not really trying to speak to the geeks with my work, but I appreciate their interest in it. One of my aims is to demystify technology and make it seem approachable, transparent, humble. I try not to impress with complexity, magic and opaque glossy touch surfaces. In that way, the work should really speak to anybody, not just the technically inclined.

What about you? Who would say is the main audience of your web-based pieces? Is there a clear demographic across the people who buy/collect your works?

RR: My web audience is huge. It’s almost 50 million visits per year. I don’t know who these people are. Some are accidental visits, who happen to find my work when they Google the word "Toilet Paper." Others follow my work for years.

As far as my collectors, they are not geeky at all, they just respond to my work and they like the challenge of owning a website as part of their art collection. I’m hoping at some point the startup/software/tech community will be into the idea of collecting art websites. They would be really good at preserving the works in the long run.

JL: It is interesting you mention these new communities of wealth. I recently had multiple discussions about that, and from all I hear it seems these people are not at all into collecting art yet, even art that relates to their own work, although they would have the financial situation to become collectors. Do you have a theory as to why that is? I have a feeling that the person who will crack that

mystery will become rather rich in the process.

RR: I consider the tech community as people facilitating a cultural revolution, enabling everyone to be an artist and to speak to their audience directly. Image software, browsers, social media, they made a whole new way of creating art possible. If you are creating a system where anyone can create and share, why would you be interested in the old centralized gallery-collector system?

I’m hoping we can live a less material life, not needing too many things, just some good screens.

RR: Has your relationship with vectors changed over the years?

JL: Not really! But I do recently get a refreshing new sense of emancipation from the preexisting tools thanks to Paper.js, which in one sentence is the effort to free ourselves from corporate constraints that Scriptographer.org was suffering from as an Adobe Illustrator plugin. It feels a bit like the buddhist exercise where you take the temple apart into the smallest pieces, and rebuild it again, with the added challenge of moving all the pieces to a new location, and adding all the missing pieces, which do not exist outside the host. In this process I had to learn a lot about the mathematics behind bezier curves, in order to be able to calculate their lengths, bounding boxes, intersections, unions, etc. It is a very interesting project that is still ongoing, and a whole lot of fun to work on!

JL: Do you program yourself? Or do you collaborate with people in order to build your works?

RR: No, I don’t program myself. I met Reinier Feijen when I was in art school. He was studying A.I. and he helped me out with some small issues. It turned out it was fun & easy for him. I had some more ideas and he helped me realize them. It’s a great collaboration… He’s very relaxed and practical and we don’t have creative conflicts, our roles are clear. I’m happy I worked with him from the beginning because if I had been programming myself I would not have been able to produce as much as I do now. I would love to work with more people at some point and realize as many ideas as possible. I love love love the process of coming up with something and creating it. That’s why I always loved the web, you can make something and publish it immediately. A direct connection between artist and audience.

RR: Were you always into the web? Or did you do a lot of offline computing before you discovered the WWW?

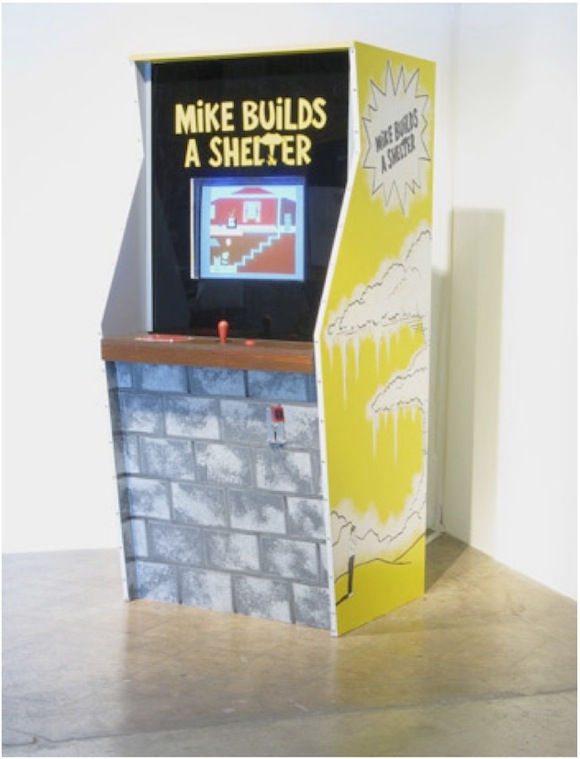

JL: I did work on offline projects before the web, for example a 3D game engine and design software around 1996, and a modular software synthesizer, coupled with the concepts of a mod tracker in 1998. But after that, I started focusing on applications online, since the possibilities of reaching many instantaneously, and working with online communities seemed way more interesting. But after a series of online design apps, toys and playgrounds (Lego Font Creator, Rubik Maker, Vectorama.org), I soon became interested into moving beyond the limits of the screen, and started exploring physical drawing devices as another way of working with the same information, as a sort of extension of the software back into the physical world.

RR: Have you experimented with vector displays/monitors?

JL: I mean to do so, and during my residence in New York in 2007, I even bought a Vectrex with a couple of games on Ebay. I was really fascinated by the aesthetic that results from a directly controlled ray in a cathode tube, with a complete absence of pixels. The idea was to write custom software in assembler for the device. But given its enclose and appearance, I felt that such a work would always feel nostalgic, and I could not find a good purpose for the work yet. I still feel that there is a piece in there somewhere. In a way the project Moving Picture Show in Chaumont last year was going back to that interest, where I transformed a 35mm film laser subtitling machine into an animation machine. The setup normally burns subtitles into the emulsion layer of the film, frame by frame, by using a galvanometer which consists of two mirrors deflecting a laser beam. The system was changed to instead draw vectors on the whole surface of the film, from a folder of pdf files, 25 per second. This became a slightly insane undertaking, where the production of 20 minutes of film would consume 10 hours of burning and cleaning film.

RR: You like to develop your own software, and you teach others to do this. How has this developed over the years? Are you hopeful that artists will develop their own digital tools? Or are most people content with mainstream software?

JL: I already explained some of the reasons as to why I prefer open software in my various answers. In the end it really has to do with freedom and control. I don’t like being tied into an ecosystem that is provided by one private company. Technology should be our friend, it should be available to all of us, and it should be dynamic like our languages are. I see technology as a core component of our culture, and just like how we all use language and participate in its constant change, we should get to a point where we see technology not as something that controls us and that we are afraid of, but as a liberator, a means of expression, and a catalyst of change.

.jpg)