From Filmgrana, a gif from Harun Farocki's Images of the World and the Inscription of War (1989)

From Filmgrana, a gif from Harun Farocki's Images of the World and the Inscription of War (1989)

Voice Dream app icon

Detail of Otto Piene's Neon Medusa (1969).

Yes, I dream of a better world.

Should I dream of a worse?

Yes, I desire a wider world.

Should I desire a narrower?

- Otto Piene, 1961

A dark gallery space is illuminated by a single ochre neon bulb, which initiates a choreographed lighting sequence comprising 449 additional bulbs, each attached with metallic arms to a central chrome orb. Neon Medusa (1969) by Otto Piene (1928-2014) evokes Sputnik and networks of cables, Cold War technological development and military communication and control, while also calling to mind constellations, Vegas casinos, and illuminated communities dotting a shiny globe. Its seeming exuberance seems incongruous with the anxieties of the nuclear age, and with the title—Medusa being the famously hideous woman of myth, who turned onlookers to stone if they stared into her face. Where the Medusa of Greek myth is the terrifying, deadly Other, Piene's piece is a different kind of Other, a technological Other, that invites our steady gaze.

A founding member of seminal postwar art collaborative/movement Zero, Piene passed away in July, leaving behind a body of work that—like Neon Medusa—invites viewers to engage directly with technology and its transformative potential. The Medusa is currently on view in "The Art of Zero: Heinz Mack, Otto Piene, Günther Uecker & Friends" at the Neuberger Museum in Purchase, New York (July 13 – Sept. 28, 2014); with "Otto Piene, More Sky" now on view at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin (July 19 – August 31, 2014) and ZERO: Countdown to Tomorrow, 1950s-60s (October 10, 2014–January 7, 2015) soon to be showing at Guggenheim New York, it seems a reassessment of Zero art for the twenty-first century is underway. We are primed for this work, given today's whiplash of rapid technological advances against a backdrop of political violence and the uncertainty of climate change—for us, as for the artists of the immediate postwar era, it is "both the seeming end of the world and its beginning."

For Piene, the seeming end of the world came early, in the form of war and Allied bombers raining incendiary explosives on targets both military and civilian. Drafted as one of Hitler's Kindersoldat, Piene spent the years after the war in a British internment camp, where he took up art, eventually taking up a formal education in Munich.

In 1950, Piene moved to Düsseldorf to attend the Academy of Fine Art. The city was, as he later recalled, "a gray emptiness...a cultural cemetery and a knowledge vacuum." Amid the city's ruins and against the backdrop of its conservative vision of the future, Piene and his fellow artist Heinz Mack—lacking access to any real cultural infrastructure—began holding one-night exhibitions in their studios. Piene, Mack and Yves Klein published the magazine Zero 1 in April 1958 and by October of that year, a group of seven or eight affiliated artists exhibited and published Zero 2.

Heinz Mack, Otto Piene, Günther Uecker. Photo: R. Van den Boom.

The group's key premises included the rejection of expressionism and subjectivity and an enthusiasm for the renewal of art via the new materials offered by technology. As Piene wrote, "From the beginning we looked upon the term [Zero] not as an expression of nihilism or as a dada-like gag, but as a word indicating a zone of silence and of pure possibilities for a new beginning as the count-down when rockets take off. Zero is the incommensurable zone in which the old state turns into the new."[1] The imagery of the rocket here is key; technology may have been associated with the ravages of war, but it also offered the only possibility for renewal.

Piene's nod to a destructive technology is telling. The potential for renewal is not an inherent characteristic of technology; rather, it can be found only in a coming together of elements that are often treated as disparate: technology, humans, and natural elements. "Zero" is the unlimited expansive potential of these elements drawn so tightly together that they amount to nothing except that potential.

This aesthetic of interdependent systems, which sought to bring together nature, human, and machine, can be seen in works by the Zero group that create an interplay between the artwork and its environment, between natural and man-made materials.

Works currently on view at the Neuberger include Uecker's 1963 Nail Structure, a grid of painted white nails on canvas, and his Column of Nails (1964), nails roughly hammered into a rectangular pillar, painted white, and perched on eroding, untouched, timber, take alien, plant-like forms, while retaining the familiarity of a man made technology—the nail. The rectangular stainless steel sheets in Mack's Untitled (1964) reflect, and therefore manipulate, the light that strikes them.

Light was a particularly important part of Zero's embrace of both technological and natural elements. Light was potent: an explosion illuminating a cityscape or a glint off of shrapnel. For Piene, the embrace of light emerged from a series of "raster" paintings, for which he used grid-like stencils to transfer materials including oil paint and soot onto canvas and paper. He came to the idea of working with light as a medium after shining a light through one of these stencils, in a move that seemed to anticipate the pixellated light fields of digital images.

Detail of Gunther Uecker’s Nail Structure (1963).

The systems aesthetic is further explored in works where artist, viewer, materials, and environment were all implicated. Zero friend Hans Haacke's Slow Bubble (1964-68) consisted of a single bubble floating within a Plexiglas tube filled with clear viscous liquid. There is an interplay between organic and inorganic, between the artist's authorship and nature's intervention: Haacke has captured air within a viscous liquid, but the air and liquid move according to fluid dynamics, gravitational forces, perhaps the footsteps of the viewer. In Haacke's terms, this is "a 'system' of interdependent processes."[2]

Such a system is on display, too, in Zero collaborator Harmut Bohm's Homogenes Feld 8 (1965) and Homogenes Feld II (1965), where small, rectangular, magnetized plastic pieces chitter inside a Plexiglas grid. The plastic pieces jump about at random in their individual boxes, though each are connected through one electric current. As with the choreographed illumination in Piene's Medusa, the work seems a kinesthetic model of interconnected processes, a visual metaphor for Zero's ethos of community and interdependence.

Detail of Harmut Bohm's Homogenes Feld 8 (1965).

Thus the disbanding of the group in 1967 did not end Piene's use of technology to foster a communal spirit through art. 280 people collaborated to create Piene’s Olympic Rainbow, a work of "sky art" created for the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich. Colored fabric sheets were stitched together and inflated to fly as a malleable, wafting rainbow above the entire Olympic stadium. The work was seen by "a live audience of 200,000" during the closing ceremonies of the games, and by a "worldwide television audience, reached by communication satellites, that numbered between 350 and 500 million. The scale of this event...was possible only with the help of modern technology and engineering." Spectacle and television, which were pressed into propagandistic service for the 1936 Olympics, here were intended to bring about "a complex interplay involving people, objets d'art, high technology, human environment, and nature."

In 1992, Otto Piene asserted: "[Art-and-technology] is alive and well and enjoying more vitality, variety, and expansion than ever before. It is currently the only expanding field in the arts; it feeds vitally into technology and industry...'art applications' have abounded since the advent of photography." As technologies have developed, so too have the outlets in which artists create. Piene's championing of the artist's usefulness to the technologist and vice versa, and for the artist as technologist, may seem to suggest a naïve optimism about technological progress. However optimistic, the implication that each new development is always a step forward is rooted in the potentiality of a countdown to zero.

Thus a notion of progress lies in Medusa's flashing through various stages of illumination: each advancement, each illumination, originates with darkness. Zero art suggested that finding a radical potential for the future must begin with a willingness to look squarely at the medusa, with an understanding of the interconnectedness of technology, nature, and ourselves, as part of a dynamic system. In our contemporary context—our networked lives, our urge to collaborate, our grappling with insurmountable geopolitical problems—Zero's wilfull belief that this potential existed is well worth revisiting.

Notes

[1] Quoted in Günter Bergaus, "Happenings in Europe: Trends, Events, and Leading Figures," Happenings and Other Acts, 270.

[2] Quoted in Nick Kaye, Site-Specific Art: Performance, Place and Documentation, 147.

The forthcoming publication from Deanna Havas and Social Malpractice Publishing

Opening the Kimono by David Kravitz and Frances Stark is now on view as part of First Look, the New Museum's ongoing series of digital projects, which will now be co-curated and co-presented by Rhizome. Click here to view work.

David Kravitz and Frances Stark, Opening the Kimono (2014). iMessage conversation.

In a recorded iMessage chat, David Kravitz and Frances Stark satirize Silicon Valley culture and sext about creative labor.

When artist Frances Stark and Snapchat developer David Kravitz discussed the idea of having sex on stage during a public presentation at the New Museum last spring, it wasn't entirely surprising.

This proposal came as part of Rhizome's Seven on Seven Conference, which pairs artists and technologists for a one-day collaboration with the prompt to "make something" and then present it to the public the following day. During their presentation, neither of their bodies was on view on stage (Kravitz came up alone for the Q&A). Instead, they appeared onscreen via a live iMessage conversation.

Soon, Kravitz was telling Stark about his friend's suggestion that they have sex on stage. After further flirtatious repartee, Stark suggested that they "open the kimono," a phrase used in Silicon Valley to describe an open sharing of business information. The oversexed exchange—fashioned in the style of a demo-day presentation—continued as the duo unveiled their main project: to "cut out the middlemen" from the "sublimated" sex orgy that is our economy. It was pure vaporware as absurdist critique. Titled Opening the Kimono (2014), a screen-capture video version of this performance is now presented as part of First Look, an online commissioning program organized by the New Museum and Rhizome.

The presentation's comedic tone and salacious content were unsurprising: Kravitz is not only a developer, but also an amateur comedian, while Stark has employed sex chat in her studio practice in the past. Perhaps most notable among these projects is her 2011 work My Best Thing, a feature-length video based on her chats with two online suitors/cam-sex partners, re-performed by generic 3D-animated avatars with text-to-speech voices.

In that earlier work, Stark drew an analogy between art-making and masturbation. As unproductive acts, both can be seen as forms of resistance to an economic system that demands constant productivity.

Frances Stark and David Kravitz during the Seven on Seven work day. Photo: Ed Singleton.

Where My Best Thing celebrated unproductive acts as a form of resistance, the Seven on Seven collaboration had a stated goal to "make something," to be productive. The resulting chat shifted the focus from masturbation to sexual promiscuity, drawing an analogy between the latter and, in Stark's words, "certain forms of creative labor." One could take this to mean that, for example, being a professional artist demands an openness to emotionally charged collaborations with strangers, and a public performance or display of personal labor. The observation also maintains its acuity beyond the art world—sharing intimate moments on social media, for instance, could be seen as a promiscuous behavior as well.

Promiscuity is the promise and threat of digital culture. It represents a possible freedom, the potential to reinvent our social roles in fluid, polymorphous fashion. But it also brings us into relationships with myriad "middle men"—all of the systems and websites and apps we use, which structure our interactions for worse and for better.

At the end of their chat, Stark mentioned the title of an exhibition that she staged at Nottingham Contemporary in 2009, which had come up in a talk she gave at MoMA the night before Seven on Seven: "But What of Frances Stark, Standing by Itself, a Naked Name, Bare as a Ghost to Whom One Would Like to Lend a Sheet?"

"hmm cool," Kravitz replied flippantly, "what does it mean?"

Instead of bringing up the visual identity of her collaborator's employer, she offered this explanation: "in order to make visible what you cannot see, you have to throw a sheet over it. that is why ghosts look that way."

Like the ghost, digital culture has long been described as "immaterial." This concept can be seen in the tech world's promotional language, with airy terms like "the cloud" standing in for the massive labor force and physical infrastructure that support our online activities today. Recently, though, commentators and critics have taken great pains to cut through this kind of obfuscation, arguing that digital culture relies on physical infrastructure, that it structures our physical world, and that code itself can be seen as a kind of material.

But the outlines of the digital, networked culture in which we live cannot be fully glimpsed in these materials. Our bodily actions, our performances, our promiscuous behaviors remain at the center of digital culture. The objects and files we create are merely the side effects of these actions; to make them visible, we must throw on a sheet.

First Look is made possible, in part, by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.

Additional support provided by the Toby Devan Lewis Emerging Artists Exhibitions Fund.

Game-Master Dragan Espenschied oversees surfers in this picture from competitor Arjun Srivatsa

At Trailblazers 7, surfing was all about different ways that indexes and taxonomies are created and used, and about excellent airhorn-puncutated stadium pop provided by DJ Smart & Outgoing.

The competition took place yesterday at the Rockaway Beach Surf Club; given the use of a one-button mouse, no keyboard, and no back button, qualifying surfers in the competition were asked to navigate a "trail" from one website to another, only by clicking. Without the use of search engines, browsing the web requires careful thinking about how websites are organized and interconnected. Often, successful trail blazing involved navigating to some link-rich environment. Whether surfers found this in editorial content (like M. Hipley's heavy usage of the New York Times website) or in the rather unsorted universe of user contributions (like Nick DeMarco always heading straight to forums and comments), finding these "indexes" and understanding the ordering of material there was crucial for success.

Every surfer sooner or later ended up on Twitter, the omnipresent social network that gives away lots of data without requiring signup. However, the public streams presented there proved not very useful for finding a link, since what single users or corporate accounts post as links over time is rather eclectic. One might remember that this or that Twitter account had some interesting link posted, but when exactly, and how to go to that point in time, when the navigational unit of measurement is not even time but single tweets?

Even websites that are seemingly ordered by topics or themes—like the typical blog format with categories, departmentalized newspapers as the NYT, or user-stewarded spaces such as the SEGA fan forums—are, with their growing amounts of content, dominated by an order of time. There is just too much material to be sorted into meaningful, non-automatic systems of order. And time is very difficult for humans to navigate in, even in calendar-based systems, clearly expressed by such fuzzy date-naming schemes as "last month" or "one year ago." In most cases, surfers would click the link to "previous page," hoping that what they remembered being in there somewhere would show up. (This turned tragic when Hipley suddenly found she would need to pay for the continued privilege of digging into the NYT archives!)

Trailblazers NY champion Joe Pugs demonstrated that a primitive yet predictable automatic ordering system would be laborious to handle, but would always lead to success. He went to Twitter every single time, but instead of heading for individual streams, headed for the list of all Twitter users, ordered alphabetically. He could count on every single entity on earth having at least one Twitter account and that they would link to their home pages from their profiles. For instance, to go to the Bad Sonic Fan Art tumblr, he had to page through quite a few "Bad [Something]" accounts, but always knew he was on the right track.

What we learn from this is that Twitter's key for being the almanac of the digital world is allowing not only persons but actually any *concept* to have an account. The only precondition for this to work is that this concept can be expressed as a series of statements, or counter-statements. This is kind of like Wikipedia, just without zealous admins going on relevance criteria deletion rampages.

Other memorable moments include:

The final result:

1st Place: Joe Puglisi

2nd Place: M. Hipley

3rd Place: Kyunghee Jwa

4th Place: Nick DeMarco

The Trails:

I. http://www.callahead.com to http://friezenewyork.com (decided in 'rush' by the challenge of finding an 'image of a globe')

II. http://sega.com to http://badsonicfanart.tumblr.com

III. http://airbnb.com to http://www.rentistoodamnhigh.org

IV. http://ted.com to http://www.reddit.com/r/mensrights

V. http://facebook.com to http://myspace.com

Post your solutions in the comments. (Heather Corcoran claims to be able to complete Trail V in 5 clicks).

Thank you to:

The following is a fictionalized account of the opening of Jon Rafman's You Are Standing in an Open Field, which was on view from Sept 12 - Oct 26, 2013 at Zach Feuer Gallery in New York.

"Zach Feuer's on 22nd Street," said Thor. He looked up from his iPhone and pointed downtown.

"That sounds right," said Zoe. "A really even number. I can picture it on their website." Zoe nodded and then coughed.

I shrugged and joined them—Thor, Zoe, and my girlfriend Ann. Thor leaned over his phone.

Thor was a tall man, handsome with thick eyebrows. At twenty-two, he was a decade younger than me. Zoe, meanwhile, had sparkly eyes. I think she was Ann's age, twenty-eight. "I haven't seen anything new by Jon in a long time," she said. "I don't even know what this is going to be like."

"I haven't seen anything, either," said Ann. "It should be good, though; Jon's really good." I looked over to Ann. Where Zoe's eyes were sparkly, Ann's eyes were windows. She smiled at me. That was nice. It helped propel me forward, into the surge of eccentric old rich people and hipsters that negotiated their way in our direction up 10th avenue. Thor ran his finger down his phone.

I peeked over to see what he was doing. Thunder rippled in the distance. I thought maybe he was looking at the Facebook page for the Jon Rafman opening we were all walking to or maybe at Google Maps for Zach Feuer Gallery's address, but he wasn't; all I saw was the image of a dark storm cloud on a weather app.

Drips. Raindrops. I looked up. It wouldn't rain tonight, I thought; it wouldn't rain on all of these rich people.

I looked around to see if anyone else noticed the raindrops.

But no one seemed to; Thor was nodding at his phone with a half-smile while Ann was busy making Zoe laugh about boys they knew from the internet. "Oh my God, I love Brian Droitcour so much," said Ann. We caught each other's eyes. I tried to funnel psychic energy through the middle of my forehead—from my "third eye"—to Ann. In the middle of my trying to do this, I bumped into a man with a manicured beard. "I'm so sorry," I said, speaking into his beard. I could see that its black color was dyed. We tried to get out of each other's way. There was cigarette smoke billowing out from his nostrils and beard. "It's fine," he said through his beard. Once he passed, I coughed. I reached down for my phone. I felt like I had to touch my phone. I did it even though I knew that it was still just as dead as it had been when I'd checked one hour earlier. I couldn't help myself, I wanted to touch the frame, just do something, just hold my phone, just do something. I clasped it, flipped it around a few times in my pocket. One second later, I pulled it out and tried to turn it on. When that didn't happen, I looked at my reflection in the blank screen.

There I was: a prematurely bald man with splotchy skin and a somewhat off-putting gaze. In the background of my reflection, I saw red clouds spread out like a torso behind the angled buildings of the neighborhood.

A strong breeze rolled up 10th Avenue. A couple more rain drops fell. It wasn't going to rain that night. Or maybe just a little bit. Not much, I thought. The force of the breeze increased, blowing something to my shoe. I looked down. It was a newspaper. Someone had circled a picture of the Empire State Building in red. Looking up, I saw this girl Monica.

Monica...I couldn't tell if Monica was an artist or just an artsy person that hung around at the same sort of things that I went to. I had once asked her to contribute to something I was organizing on the internet—it was all writing. I liked when people wrote. Monica told me that she wanted to write something about how capitalism and technological progress had unequivocally won in their struggle against the natural environment. She wanted to write about how there was now nothing to do to stop the Earth's ecology from rapidly winding down and all life on "Gaia"—her term—from perishing. I agreed in spirit, but worried that she might not be able to make a strong argument. It didn't matter; she never ended up sending me anything. I watched Monica pass me by and then I turned back, but I didn't see Ann, Zoe, and Thor. Oh no, I realized, there they were. They had turned onto 22nd street, angling toward Zach Feuer.

I caught up to them and we walked through a crowd of smokers who were standing outside of the gallery's storefront windows. I recognized Janet, a curator that I liked.

"Hey, Jan-Jan, how's it going?" said Ann. "What've you been up to tonight?"

"Annie Poo!" said Janet. "It's gooooooooood, how are you guys? Where you coming from?"

"Lonely Ladies," said Thor, referring to the show we'd just been to, Lonely Girl. The show was all young female artists whose work is their internet personas. Thor made an over-the-top frown-y face and Janet reciprocated with an even more frown-y face.

She recomposed herself and said, "Oh yeah, I wanted to see that…I think. What was it like inside? I couldn't tell what it actually was."

"Ya know, said Zoe. "Art. Paintings. Sculptures. It was okay."

"Wait, I thought it was internet stuff."

"No, I don't know, that part was confusing. There was one computer, I think. I liked it, I think. I liked this one piece that was a drippy mop. It's nice that it was all women."

"But, yeah, the way he's presenting the women. I don't know, it just—whatever."

More raindrops. We all looked to the clouds—they were a deeper shade of red—vermillion.

"Well," said Ann, "if it ends up raining as hard as I think it will tonight, Lonely Girl is going to need that drippy mop—those floors are going to get filthy!"

I laughed a dumb laugh at that. Hearing the sound of it, I made a serious face. "How's Jon's show?" I asked, changing the subject.

"I don't know," said Janet. "I haven't really had a chance to see it honestly, I'll have to come back another day. There are too many people in there."

I looked in through the windows. There were indeed a lot of people. Maybe two hundred. More? I don't know. I can't tell numbers. The crowd was a mixture of young people, many dressed in athletic gear with a techno-future style, and older art world people in designer glasses. I noticed large vinyl letters on the wall—JON RAFMAN: YOU ARE STANDING IN AN OPEN FIELD. I scratched some stubble on my face. Good for Jon, I thought; he'd gotten off of the internet. Me, not so much. A few years before, there was a moment where I was writing about artists, including Jon, that made work about internet culture and I was getting some attention from the art world. If I would have capitalized on that, I could have gone somewhere, spoken on panel discussions, stuff like that, I don't know. But instead my work became more hermetic and I haven't really recovered my footing. GENE MCHUGH: YOU ARE STANDING UNSURE OF YOURSELF.

"Alright, I wanna go inside and see what the deal is," I announced. Ann, Zoe, and Thor nodded.

When I opened the door, a low rumbling noise caught my attention. I looked ahead to see if I could tell what it was, but the pathway to the main gallery was bottle-necked with small groups of people greeting each other and looking at their phones. I pushed my way through, past DVD sales racks, each of which displayed brightly-colored DVD cases. This was one of Jon's pieces—not the individual DVDs, but the whole installation of display racks. Some people were asking their friends whether or not you were supposed to take one of the DVDs, as, like, a thank you for coming to the opening.

I walked into the main gallery—a huge open space. I'd forgotten how big Zach Feuer was. Without walls to break up the room, the visual sweep of the place, along with the din of several hundred voices echoing twenty, thirty feet above the work, took on a collective buzz. The work—sculptures, videos, prints, and wall reliefs—all seemed inspired by video games and the apocalypse. One of the centerpieces was a long row of body pillows with anime-style drawings of naked Asian women in sexually explicit poses. I knew what these pillows were —they were a real product in Japan for people too shy to interact socially. They function as surrogates for real bodies. Near those were these three busts that looked like human beings morphed into digital abstractions, characters, I imagined, from an artsy, sci-fi video game. The color of each of the busts was too intense for nature; it could only have come from a lab . And past those was the other centerpiece of the room, a hyper-kinetic video. The video had extremely poppy, violent imagery, much of which was also in an anime style. Taken together, these references and themes infected the physical space of the gallery with a virtualized feel, as if it was a three-dimensional video game space. Perhaps, I thought, the objective of this game was to accrue more and more professional and social capital in order to advance to the next level of your art career. Okay, here's my first chance: a curator wearing a leather jacket that I'd always wanted to meet was wandering around by herself, reading the press release. If I went up and talked to her and made a good impression, I would have gotten ten points. If she thought that I was awkward, I'd lose ten. By doing nothing, I'd just lose one point. She seemed like she was pretty deep in thought; I wasn't going to bother her. So minus one point. I can deal with that.

Where's the bar, I thought. I looked around the room. Ann, Zoe, and Thor were each talking to other people, getting those points. I walked over to the other side of the room. There was a crowd there, maybe that's where the bar was. Before I got there, I saw this piece that I liked a lot—it was a sculpture of a laptop that had been coated over with green reptilian skin as though the skin was a spreading organic growth. It was uncanny. Once a year or so, I have a nightmare about alligators. I think of them as a distilled form of evil or something. I read St. Augustine on evil in high school. When I was a senior, I spent an entire Computer Literacy class searching "st augustine evil." I found pictures of alligator claws.

I heard a low, rumbling noise in the gallery.

I spotted the bar, but before I could reach it, I ran into my friends Josh and Dan. "Hey, guys," I said. I already knew them pretty well, but maybe I could still get a few points.

"Hey," they replied. Dan was tall; Josh was average size with a wispy blonde beard. They wore shirts with the top button buttoned—Dan's shirt was colorful; Josh's was gray. Their eyes darted around.

"Hey," I said, "Which piece makes that low, rumbling noise?" They didn't know what I was talking about, which must have meant that I was confused about having heard any noise like that. And they would know—while Jon made his videos and came up with the ideas for the sculptures, it was Josh and Dan who fabricated them into actual objects. Hardly anyone knew, but they were completely integral to the show.

"Everything looks really great," I told them. "I especially liked that computer that's covered with reptile skin." Their eyes brightened and they nodded to me.

"Yeah," said Dan, grinning, "It has a really weird feeling." I looked over at the sculpture again and turned back to him, nodding in conspiratorial agreement.

"It's nature overwhelming technology," I said. I grinned an intentionally evil grin.

Josh scanned the room. "You know, I'm actually really happy with how it all turned out in the end. I have to say. It's a good turn out, too, which is nice. For Jon."

I followed Josh's eye. People were packed near the front. Through the storefront windows I could see that it was dark outside and I tried to remember if it had been dark when we arrived. I looked closer. There was a red tint to the darkness.

"What are you guys doing after this?" I asked.

"I think we're going to that bar in the East Village with everyone else," said Dan.

"Yeah, that's where we're going, too," I said. "Wait, why is it in the East Village?" A flash from someone's phone caught the corner of my eye, sort of stinging it.

Before they could answer, a woman in a wife beater and tilted baseball cap came up to Josh and Dan. She told them that everything looked great and that the turnout was really great. I kind of wanted to leave and go home with Ann. I was tired of trying to get more points. But Ann was busy. She was talking to this couple that I vaguely knew. The couple was older and their faces were wrinkly.

Jon Rafman walked by me. He was talking to an important looking person, maybe a collector. He acknowledged me with a wave, which was nice of him, and then stopped and we chatted a little bit. Twenty points, at least. The points popped up with a colorful on-screen graphic—glistening gold. He introduced to me to the collector (it might not have been a collector) and Jon told him that he still quotes this one thing I had written about his work a long time ago. It was about his series Brand New Paint Job. I had said something about how…never mind, it's kind of complicated and not worth going into. The point is, every time I see Jon he tells me about how he still quotes this one thing from several years ago. It's nice of him. I just wish I had something else going on in my life worth talking about. We joked around a little bit and he said goodbye to me with a good-natured bro-hug.

As soon as he went away, I noticed that the lights in the gallery were too bright. It had been nice to talk to Jon, but after he left I felt like I didn't have any points. I wanted to unbutton my shirt, but decided not to. I saw this artist named Claudia that I had hung out with a few times. She was in a hurry; she shot past me and disappeared into a crowd. I thought of texting her and telling her to come and find me because I was bored. But, of course, my phone…If I would have just had my phone I could have been communicating with people and getting points, but I wasn't. I was just losing more and more points.

Someone took a picture of their friend. After the flash, the friend asked to see the picture. When she saw it, she said, "Oh my God, it looks like my skin is falling apart!" There were a bunch of other flashes, bright white ones, from outside the gallery.

Zoe came up to me and said, "What's up, dude?"

"Nothing, homey, what up with you?" I heard that rumbling sound again. I asked Zoe if she knew which piece that rumbling sound was coming from. She shrugged. I asked her if she knew what she was doing after and she said she was feeling sick and, plus, with the weather, and we both looked outside. I tried to spot Ann; I wanted to see if Ann wanted to leave with Zoe. But Ann was still in conversation with the wrinkly couple. Everyone in their triad looked very still. I wondered what time it was.

"Do you want to get a beer?" I asked.

"Yeah, alright…." We went over and waited in line at the bar area. Once I had a beer in my hand, I cracked it open and guzzled back a bunch of it. My cheeks tingled. I looked at the reptile-skin sculpture again. The monitor displayed video from a first person shooter video game. I swallowed a bunch more beer and noticed that I had already had about half of it.

I clinked cans with Zoe and then finished mine in a few more big gulps, burping a little. Zoe said she thought she was just going to go home because she felt sick. I said I understood and hugged her goodbye. Then I went to get another beer. "Oh, hello," I said. I saw Thor. We started saying "Hello" to each other in these low, very slow voices and then we continued to talk about the sculptures and Jon's work in these same low voices. When my voice was at its lowest and slowest, I said, "The turnout's really good, don't you think?"

Jerry Saltz, the critic, walked by. A hundred points easy. No, I realized, it wasn't Jerry Saltz. Zero points. Two points. I didn't know. Negative points. I looked at my phone. Sweat was caked on the screen. I looked up to Thor and asked him if he thought that art collectors would be into this show and he said maybe. Ann came over. "Do you want to leave?" she asked. "I'm ambivalent about going to this after party. I'm kind of exhausted." She looked over to Thor. "What are you thinking?" You wanna go to this thing? I never heard of the place, though. And the East Village is so far, but, still, I don't know, it might be fun."

"Yeah, I'll go," said Thor and I said the same thing.

"Alright I'm going to find Zoe," said Ann. I was going to tell Ann that Zoe had left because she was sick, but, before I could say anything, I saw that Jasmine, an artist that had a really big following on the internet, was drenched. The gallery door slammed behind her and a gust of wind made a woosh. Ann turned back and saw me staring at Jasmine. I looked outside. It was pouring rain—Jasmine had just come from out there. The door swung open again; a few more drenched people dashed inside. They clearly didn't know what show this was. One of them—a girl too wet for me to be able to tell what she looked like—stomped over to the reception desk and grabbed a press release to dry her hair and glasses. The rest of us who had already been in the show were watching, mildly shocked, as the drenched people said, "It just started, one second it wasn't there and then it was there…" We all looked out the window. There were insane amounts of rain. Everyone clutched their phones, glanced at their phones. More drenched people, including Zoe, rushed inside. Their umbrellas were broken; a crack of thunder literally made us all jolt.

I wanted to move around a little bit. A bead of sweat trickled down my forehead. I went back into the show, guzzling down a bunch more beer. Some people in the gallery were looking out front, trying to tell how bad the storm was going to get and comparing their guesses with other people. I looked over to the laptop—the one covered in reptile skin. Just below it, a wet puppy was shivering. The puppy didn't have a leash. I looked around, but it wasn't clear that its owner was nearby. I put my hand in my pocket and touched my phone. I had this idea I wanted to take a picture of the puppy. It looked kind of funny, all wet and shivering. It was suffering. It wasn't funny—the puppy wasn't funny—but maybe it was funny that I had taken the picture? Was it funny to do very mildly evil things? It didn't matter. My phone was dead.

The puppy ran over to Ann. Ann crouched down and said, "Hi, Mr. Friendly! Hi! Don't you smell like a wet dog?? Yes, you do!" I walked over to Ann and the dog and heard someone ask, "Did this gallery suffer damage during Hurricane Sandy?" Another person asked, "Will I need a a better umbrella if I'm going to stay in New York?"

Because the rain was coming down so hard, I thought that it would finish quickly. That's what I told Ann and she said, "Don't jinx it. Besides, you don't know. This seems like it might keep going." Ann was smarter than I was and she knew a lot about the weather. I thought maybe she was right. I stepped in a little puddle of water and walked back into the crowd near the entrance. Thor said something about a spiral in the Empire State Building, but I must have misheard that.

"I'm gonna get us a cab," said Thor, pressing things on the screen of his iPhone. "I have this one app that calls cabs…well, it calls town cars, actually. Uber." Everyone thought it was a good idea to use Uber.

"Yeah," I said, "let's just go to the after party."

Thor shook his head and made a clicking noise. "Shit," he said. "The network is down." He looked up at us. "It says the Uber network is down right now." He checked with some other people who were also trying to use Uber and the consensus was that the storm had definitely shut down the network. It wasn't clear if this was because there were so many people trying to use the app at once or if the weather had disrupted the service more directly. I rubbed a hole in a fogged-over window and saw raindrops pelting through ambient street light. More people rushed in and I found myself stepping out through the door and, oh my God, the sensation of passing from a controlled gallery environment to raw, blistering nature made my heart skip and I took a series of deep, watery breaths. A moment before, I had had this compulsion to go outside and try to find a cab, so I just did it. I didn't want to have to rely on the internet to get us a cab; I wanted to go out into the real street and really find one in the real, natural world. It just seemed like something I had to do or I would feel weird all night. And so I did it, I went out. I couldn't see anything; just flickers of light and broken tree branches on the street. Eventually my eyes adjusted and I saw 10th Avenue. I ran in its direction and the rain hurt my face. I saw a cab turning onto 22nd Street, but it wasn't available. None of these cabs would be available, I realized. What was I even doing out there? But, wait, there was another one…that…yes, it was stopping. Yes, its availability light went on. Oh, man, I'm going to get this cab, I thought. I'm really going to get it. And then I'll pick up my friends and they'll be thankful. I ran up to the cab through the rain as children in Transformers t-shirts scurried by me, chittering beneath an enormous blue and white umbrella. I was within twenty feet of this cab. I started to trot. It would feel good to be inside. I imagined the moment when the door would shut and I'd encounter total warm dryness and the comforting blue and yellow light of Taxi TV that would play off the raindrops streaming down the window. I imagined how money would start accumulating and how progress would be happening and how I would have done it all on my own. I waved my arms at the cab. The guy must have seen me. Just a few more feet…The cab's availability light shut off. Oh no, wait…what? The cab drove away. Before it completely passed by, I looked in. It was the wrinkly couple. How did they get in there? Well, it didn't matter; the cab was gone. Rain was streaming into my face and mouth and I swallowed it like I was guzzling beer. I told myself to be Zen about this and just walk at a normal pace and not let the extremity of the situation affect my demeanor, just, if anything, I told myself, enjoy this experience for what it was rather than freaking out. I tried to funnel anxiety through the middle of my forehead. I started feeling very cold, though, and I shivered and my body wasn't allowing me to be Zen about everything. I started to jog back to the gallery and I tripped a little bit on the sidewalk. I looked up and saw Ann, Zoe, and Thor getting into a black town car. Ann was yelling, "Genie, come on!! Get in!!" I ran up, opened the back door, and hopped in. I looked around and they were all gawking at me, thinking it was funny how utterly soaked I was. Ann said that this was the town car from Uber. She said that even though it didn't look like Uber was working, the request had been put through and Thor had just gotten a text from the driver that he was out front. It had all happened just after I left the gallery. I nodded, not knowing what to say, and told the driver, "East Village."

Gene McHugh is a writer based in Brooklyn.

From the cempontraoryartdaily tumblr.

Cancer Baby by LuYang from LuYang on Vimeo.

Allan Sekula and Noël Burch, still from The Forgotten Space (2010).

I woke up at the chime, looked at the mobile. New work available. I clocked in, made coffee, sat at the desk. Two hours of work right away, even before Twitter. Felt accomplished. I invoiced, and collected.

I met Sandra for breakfast. She's in Miami. She had the ceiling open to let in the sun. She got into a new task queue, editorial work. It's good work, she said, even though the pay isn't quite as good as advertising. What's the difference, I said, sipping my Bloody Mary. Different algorithmic authors, same algorithmic grammar problems.

We're in Brussels. I had put in for an unstack, thinking I'd get out and walk around this afternoon. I felt the slight bump as I was offloaded this morning, while I was still drifting in and out of sleep. I open the ceiling, see gray rain clouds above. A few fat droplets make distorted bubbles of light and color against the sky-looking lens. Maybe not. I query the schedule. Next stop is St. Petersburg, on Saturday. Weather report says sun. I'll have a walk along the Neva. It's been a few years.

Three hours of work. Probably three-fifths work, two-fifths Twitter, judging from my task conversion rate. There was another hurricane in LA. Images of houses and cargo containers tipped off their barges, floating upside down in Hollywood Bay. Thousands of them, some floating high, others with just single triangular corners showing above the muddy water. Green for homes, red for cargo. Like autumn leaves floating on a pond. Improperly ballasted carriers, people say. I invoiced, and collected.

Exercised, showered, had a little personal time on the bed afterward. The new toy is great, very responsive. Five star review.

Date with Heather tonight. Our circuits will take us both to Thamesbay at the same time in the fall. We've scheduled ourselves to be neighbors. I look at the edges of the door, behind the GIF screen I bought in Tunis last year. I imagine her, right through that door, every minute, for an entire week. Will we spend more time in her house or mine? She knows how to cook better than I do. But I like my bed. I imagine her in it. We're watching a film tonight, Solaris. I suggested it. She's never seen it. She likes noir, I like science-fiction. I think she'll be into it.

I think about paying for a circuit change. Transport across the Arctic Circle to South East Asia. A month in transit at most, and then tropical sun, newly built beaches with real sand, imported from Mongolia. My work's not good enough to afford that circuit. I'd need a queue upgrade, or even two. And then there's Heather. I could go after Thamesbay. Maybe just for awhile.

Three hours of work. I invoiced, and collected. Dinner—just my usual rice and beans. The beans are from Italy, large and white. Amazon special, via a passing container heading north to Scandinavia. They swell up plump in the hydrater, flavor the rice via an hour in the cooker. I went to Venice once. The new one, near Milan. I left the house and went to a restaurant a short walk from the barge port. I bought an antique digital wristwatch from a child running a flea market stand. The child was pale, wearing long sleeves with a veil. Living outside in a city, unable to afford UV block, she never exposed herself to the sun. The watch looked good against my dark wrist, black rubber on black skin. I don't wear it, but it's in the waterproof locker underneath the bed. I still remember how the rice tasted there.

The date was good. We got halfway through the film and then started fooling around. She pinged my toy, which I had quietly made aware to her, and we opened up a video feed. She asked me to show her my chest. For a long time, she just wanted me to show her my skin. My sternum, my nipples, the scar under my collarbone, my breast. She used her head camera, showed me her hand touching me on her screen. We synced toys and fucked. We stayed up talking for hours, after the film had played out, synced on our walls beside our beds. She talked mostly. I listened. She was in the Baghdad Shoals, I think. The lights were tuned brighter much later where she was. I didn't ask. I just wanted her to keep speaking to me.

After we hung up, I didn't feel like going to bed. I worked for an hour, invoiced and collected. I uploaded a video post. Browsed for new GIF art. Fell asleep watching a collection of classic Pokémon cartoons.

I woke up at the chime, and looked at the mobile. New work available. I didn't feel like it, and moved over to the couch. I checked Twitter. Fighting in the Ozarks, drone strikes against the Free New Orleans Navy off of Pine Bluffs on the Mississippi Sea. People were calling for sanctions, which probably wouldn't come.

I looked at the circuit routings, searching for some sort of deal. Four-month circuits between the Horn of Africa and Antarctica. I could afford it. But all that time on the ocean away from the coastal canals, and nothing interesting but fish farms and gambling on the seventh continent. There was the Appalachian Seaboard of the United States, getting cheaper by the day with the violence in the Midwest. Sandra liked that area. We could meet up, probably. Have a drink in person. Maybe be neighbors for a bit. We had always been close.

Then I found it. Two-month circuit, from Lima through the Nicaraguan Canal through the Colombian Archipelago and back. Last-minute deal, six-month commitment, at a rate just a little higher than what I was paying now. I did some quick math. I could do it, though it was a stretch. Maybe apply for a queue upgrade.

I signed the contract. Currently on pay-as-you-go, I could transfer immediately. I heard the far-off, muted sound of groaning steel, the increasingly close bumps as the cranes began shifting the stacks above me. I had, apparently, been reburied over the night as the barge loaded cargo. I opened the ceiling, and looked at the grey clouds above us. Still Brussels, I concluded. I heard the loudest shift yet, which must have been the unit above me being lifted away. The screen showed nothing but clouds, rolling slowly in the wind. I felt a slight tremor as my house was born up, excised from the barge stack to whatever ship would take me across the Atlantic to South America. The ceiling flipped to cool, white LCD standby until my house was plugged into the network of the next vessel.

Dimmed the ceiling, thought about making coffee. I thought about what I was going to tell Heather about Thamesbay. But she knew me. She knew what life was like. She would understand.

Dystopia Everyday is a short fiction series that takes the form of user stories set in the near future. Previous works include Martine Syms' "Her Quantified Self" and Nicholas O'Brien's "Forgetting the Internet."

This is Rhizome Today for Thursday, August 14, 2014

Rhizome Today is an experiment in ephemeral blogging: a series of posts that are written hastily in response to current events, and disappeared within a day or so. At the end of each month, we'll republish highlights from the series in a more selective and polished form. The latest post can always be found at http://www.rhizome.org/today.

Dread Scott, Sign of the Times (2001)

Peter Watkins, Punishment Park (1971)

James Baldwin, via Huw Lemmey:

When a city goes under martial law, everybody in the city is under martial law. If I can't go out and buy a loaf of bread safely, then neither can the housewife. That’s why she's on the range, learning how to shoot a pistol, in the land of the free and the home of the brave.

They're confusing themselves with the Indians, you know, they're back on the wagon train. But we all know who's in the streets of America. We all know to whom we are referring when we talk about "crime in the streets". We know the son of the president of Pan Am is not in the streets. Only one person in the streets—that's me! And they’re plotting to shoot me, in the name of "freedom", dignified by "law". And I'm supposed to agree.

No, no, no sir. I won't be disorderly no more. Alas, the party is over. The question is "what shall we do?". Everybody knows it. The question is in everybody’s lap. From Washington to London, to Bonn. Everybody knows it. They're trying to figure out what to do. We should figure out what to do.

Martine Syms, Reading Trayvon Martin (2012-ongoing)

Tracy Clayton's Twitter list of people actually in Ferguson right now.

Isaac Julien, Territories (1984). Still frame from video.

Lena NW's Fuck Everything (2014)

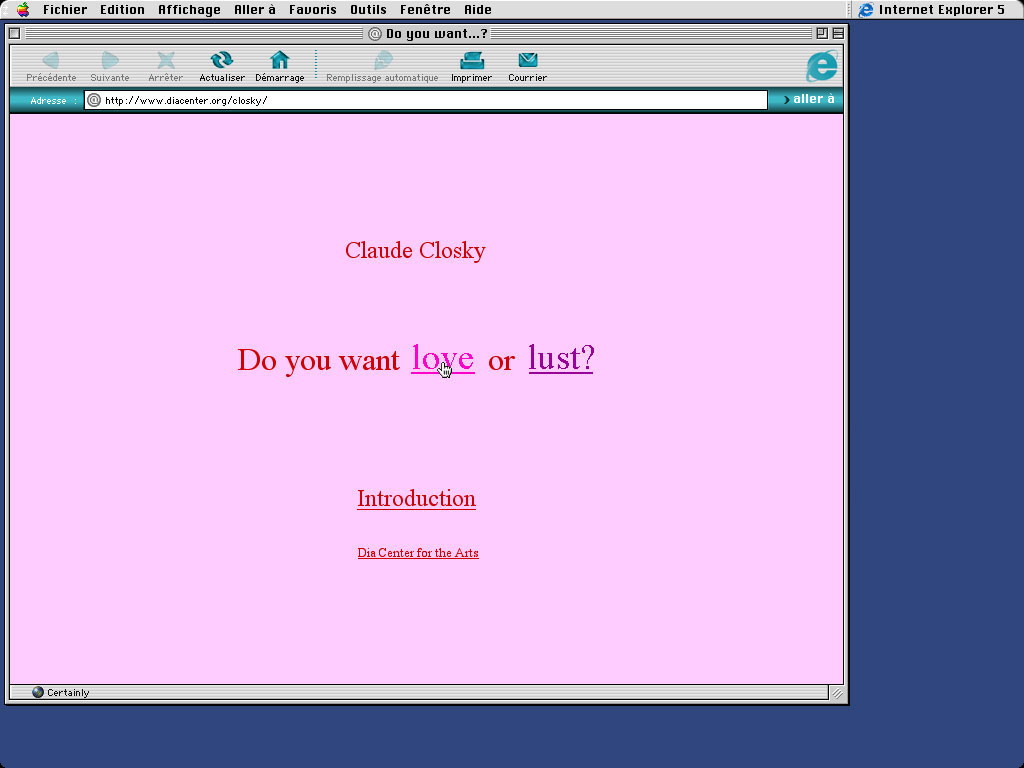

Screen shot from Closky's Do you want love or lust?

Your lover wants to move in, and you have a choice: you can say, "ok, I'll try it for a weekend and then we'll see" or you can "threaten to break up right now."

Then, your boss gives you a compliment. You can either: "say ironically, 'soon you won't be able to afford me,'" or "mentally calculate how much more you will ask him for."

You choose, you choose again, then you choose again. Each time, you are presented with another choice, an either/or. It's impossible to predict the outcomes that either decision might yield, but you choose carefully, expecting that each choice will shape your future path.

This is the sprawling question set of Claude Closky's 1997 Do you want love or lust?, an early web-based hypertext work that draws the user/viewer/player into what seems like a CYOA (choose your own adventure narrative). By making a choice—clicking love or lust—you enter a fictional, and emotional, space where you are the protagonist of this story.

But Closky turns this against you. The questions don't seem to end; each choice you make seems to bear no weight on the next question. This is futile. The questions change, the color of the text on the screen, the color of the screen, but not the context, and not you. You are a protagonist with no agency, no authorship over this unfolding narrative.

Do you want love or lust? could be read as a wry sendup of the promises of hypertext literature, a cultural form of note among early web practitioners in which users used hyperlinks to navigate from one piece of text (other media were also incorporated) to another. Specifically, proponents of hypertext literature often argue that it demands an active reader who shapes their own narrative destiny, if only within a predetermined set of potential outcomes.

In Closky's work, though, the active reader is revealed to be a Charlie Chaplin in the factory, operating a complex apparatus to no discernible effect. Clicking on his hyperlinks will move you forward, but only inside a closed, random system; it seems to emphasize the arbitrariness of decision-making in hypertext literature. Is all interactive fiction equally arbitrary? Or does it, at times, allow users to make meaningful decisions, to experience a real sense of agency?

Ten years later after Closky's work, in 2007, developer and interactive fiction writer Chris Klimas—inspired by the history and potentiality of the click and a fascination for interactive fiction, gaming, and open internet projects—began coding a hypertext development environment called Twine. Twine was released for Mac and Windows users in 2009, with projects easily sharable and usable via HTML. The beauty of Twine was, and is, its ease of use — little stands between you and your ability to express via hypertext. According to Twine's website, "You don't need to write any code to create a simple story with Twine, but you can extend your stories with variables, conditional logic, images, CSS, and JavaScript when you're ready."

Twines are intimate, deceptively simple game-like online experiences composed of clickable text crafted into modular, recombinant narratives. It stands on the history of hypertext experiences as imagined by Vannevar Bush and Ted Nelson, and brought fully to form on CD-ROM by Shelley Jackson and online by Mark Amerika, but evolves from these works in that it takes advantage of the capabilities of modern browsers and the ideas of a large base of artists and authors.

Despite its simplicity and flexibility, Twine remained a fringe platform with relatively few users for the first few years of its existence. The platform was used primarily by writers as a means to outline stories and uncover potential narrative threads. Though it differed from other interactive fiction software, its identity and utility to writers and artists remained untapped. In 2010, rumors even circulated that perhaps the platform was dead.

Then, in 2012, a shift in Twine's popularity occurred beginning when Anna Anthropy sang its praises in her book, Rise of the Videogame Zinesters as a means to write text-based games without a need to code. In a recent article "Untangling Twine: A Platform Study," Jane Friedhoff describes how, "Within a year, there was a flurry of activity including a formal tutorial by Anthropy in September, a Twine tutorial at a game jam in September, Twine-specific jams in September and October, and manifesto/tutorial by Porpentine in November." Friedhoff cites this as the moment when Twine went from a cultural backwater to being a significant platform for the "marginalized voices" including the LGBTQ communities, racial or religious minorities, and women.

Friedhoff posits that the relatively spare aesthetic and easy programming allowed it to be journalistic and expository, and that Anthropy's specific promotion and use set the tone for the content of a majority of Twine games. The games' ease of use, creation, sharing, and participation resonated with some marginalized groups whose efforts to either raise awareness of (and perhaps change) their status as marginalized, or to gain strength in numbers, could benefit from the platform.

Moreover, the sense of first person identification that Closky détourned in Do you want love or lust? can be a powerful tool for such groups. Not unlike a LARP, hypertext fictions allow participants to engage experimentally in alternative realities or subjectivities or behaviors. Hypertext users may experience new kinds of freedoms and new kinds of consequences.

Anthropy's queers in love at the end of the world (2013) (discussed here) or The Hunt for the Gay Planet are two very different takes on intimate experiences: one models what you might do with a lover in the ten seconds before the world ends, and the other sets you on a herculean search for a vast (planet-sized) queer community. In one game, death is imminent, a fixed time limit removes inhibitions about performing specific gender roles and lends the work an emotional and polymorphously libidinal charge. In the other, frustrations mount as each turn you take yields no lesbians, no one gay and nothing queer; the sense of isolation experienced by many on the queer spectrum is made achingly manifest.

As the experience of clicking a link is so commonplace, Twine games immediately evoke our day-to-day vulnerabilities and the innate risk of clicking, of being asked to make a decision without a full understanding of what the consequences might be. The subtle simulation of danger and uncertainty in the games parallels the daily risk of individuals who belong to groups more likely to experience mistreatment in society.

To dramatize this, many Twine games serve (like Closky's) to highlight the arbitrariness of the user's decisions, their lack of agency. In Tsukaretablues's Twine We Were Made For Loneliness, you are often given three options at the end of a segment that appear to link to a next part of the gamified story. As you move the cursor over the text it goes from red to black, becoming crossed out and then, unclickable. You realize there is only one option.

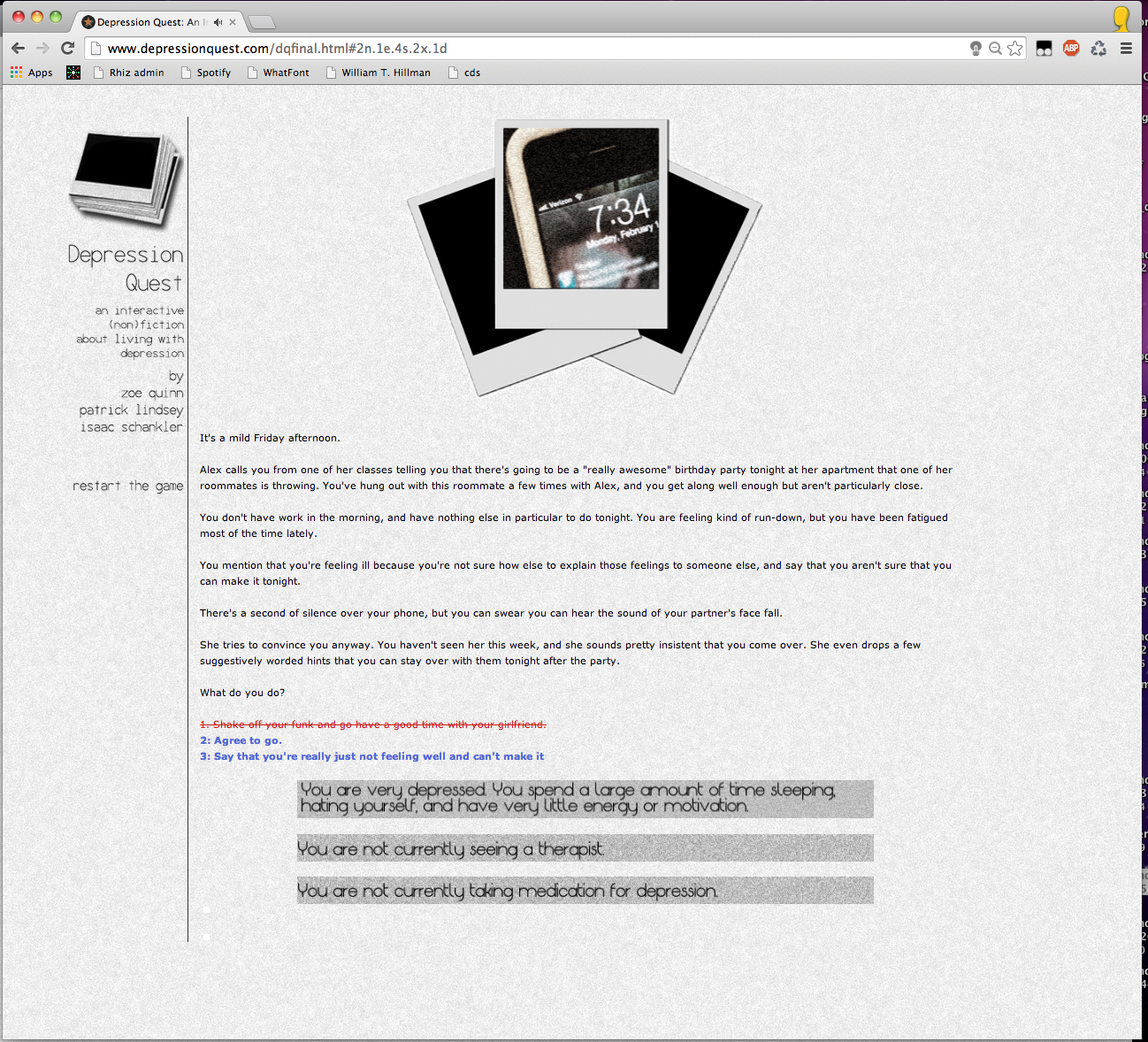

Zoe Quinn's Twine-built game Depression Quest (2013), which was made available for free in the wake of Robin Williams' death, uses this crossed out text visual motif to emulate the self-restriction of living with depression; you, the player, the sufferer of depression, think, and know, that when you have trouble sleeping you could "Force yourself to sleep," or "Just close your eyes and let it happen" but the reality is, as evidenced by the only bold blue text on the page, that your only option is to "Go to your computer. Sleep is clearly not happening no matter how long you lay here."The way you may want the story to go is in red, crossed-out text. As a reader and player, you fight to make the best possible choice and hope it gets you through to the next screen.

Zoe Quinn, Depression Quest (2013)

Twine text-based games emulate our limited agency within our daily experiences with work, lovers, friends, art, life, and as such have proven a valuable cultural form for people who, in their daily lives, must work within a limited set of choices. The text, clicks, and roundabout narratives within a Twine game illustrate the anticipation and uncertainty we feel navigating the internet, or life. You have the choice of what text to click, but no control over what comes from that click. The hypertext of Twine enriches an otherwise ordinary narrative with the innate confusion, messiness, "reality" of the player. They are what draw us in to the narrative, but also a reminder of the narrative's bounds. Each click through a Twine game reiterates what it really means to win: accepting the limited choices at hand and moving forward, trepidations aside.

The mission to create a zine-like culture around gaming articulated by Anthropy, allowing games to be personal and lo-fi, continues to build today, two years after Anthropy's initial proclamation. From February to April of this year, Richard Goodness curated "Fear of Twine," an online exhibition of sixteen Twine games. The goal was not to demonstrate the platform's ease of use, or to promote use within the LGBTQ community, but to show how diverse it could be as a gaming tool. Though Twines are primarily text-based, and often narrative, as you pick and choose your way through one, you feel compelled toward the reward of a successful narrative, the ending you want, hence they are gamified stories. Goodness senses a continuing rise in the indie gaming scene, helped by Twine. "Twine," he says, "seems to have arrived at a point where people wanted more things from videogames, it is accessible enough for lots of people to make games, but complicated enough that people can make interesting work." Just as the photocopied zines made your voice feel heard or the recorded-in-a-garage sound made Beat Happening sound like all your unrequited crushes, the fast and dirty creation and aesthetic of Twine games makes them a perfect outlet for our reverberating, repressed emotions, and for modeling possible freedoms and real world oppression.

Screen cap from Coleoptera-Kinbote's Twine Duck Ted Bundy, part of Goodness's 2014 "Fear of Twine" exhibition.