![]()

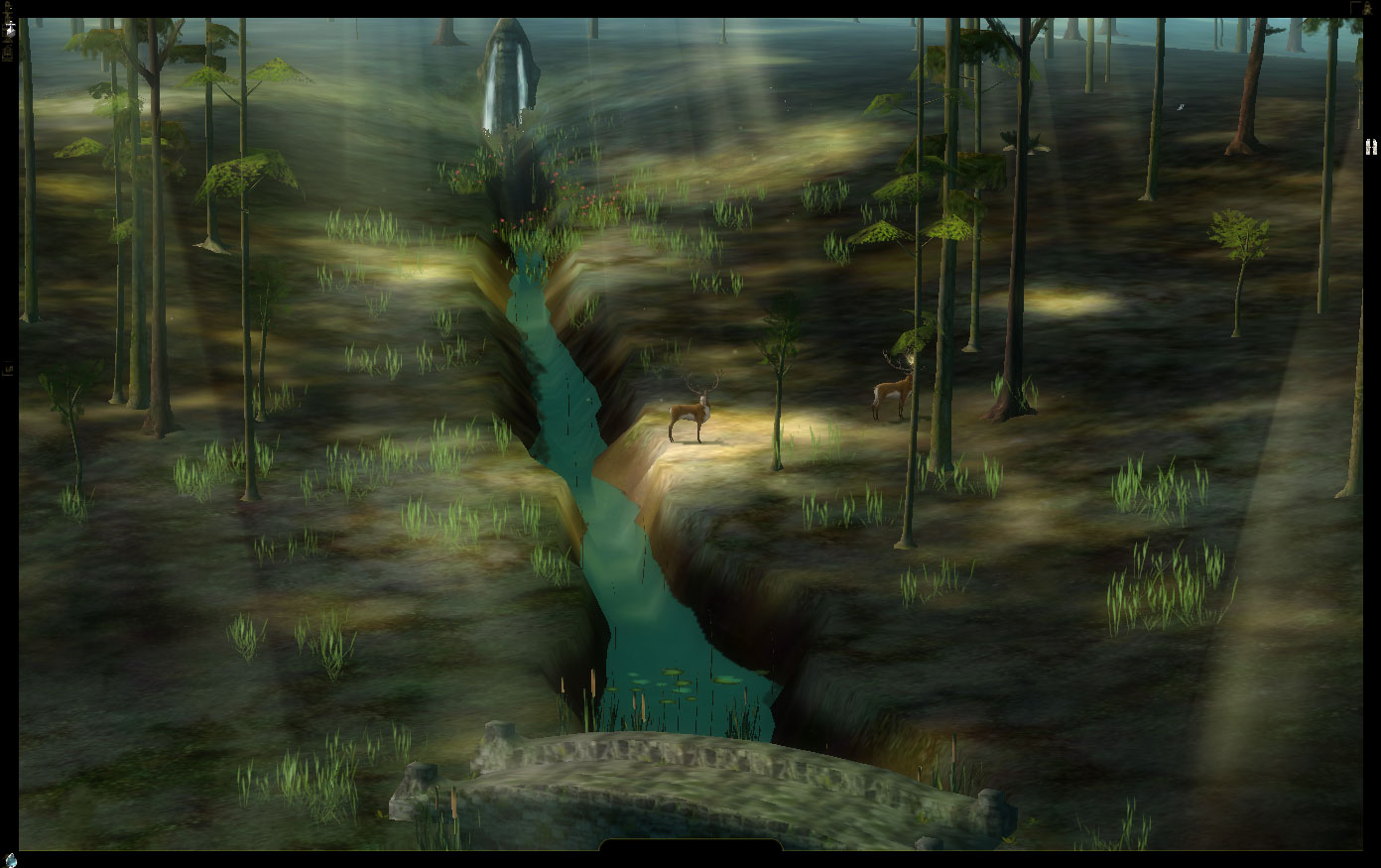

Untitled, Image, 2013

I

Louis Doulas: It might actually be interesting to start with your mother. I didn't know she was an artist until you mentioned it the other night. She makes collage work similar to your own (or is it the other way around?)

Aaron Graham: Although there's a huge generational gap between my mother and I, we find ourselves in the same sort of position: how do you access an art world, or an audience? For example, my mom considers herself an artist, and is one, rightfully so, but who does she show her work to? She doesn't really have an art world connection or gallery plug—she's also not necessarily interested in that either. Anyways, I find myself in a similar situation. It's funny, I graduated from school, and am looking for the next step, but when I look towards the art world and all the galleries, I can't seem to muster up the interest in playing that game, and I think much of my attitude, or position, stems from my political involvements with Cooper. What was really significant for me was the Cooper lock-in we did in December, which was my first real experience with direct action. That lock-in lasted a week and it was one of the best weeks ever. I think that once you taste these things, it's hard to go back to anything else.

I went into the whole thing pretty skeptical about how it would work out. I thought that the entire action might last a couple of hours, but it ended up lasting a week—and I think it was fairly successful. Everything started going our way and at some point you realize "Holy shit, when you do this type of thing it really works!" It was my first taste of something like that, and since then I've been looking at similar movements and actions that are happening around the world. For instance, the Tar Sands Blockade; these people are fighting the construction of the Keystone XL pipeline by just locking themselves up to things everyday. That is so much more exciting to me than art that's critiquing something from a distance. Unlike so much art that you see, direct action doesn't go in or out of style.

LD: Do you try and separate these two roles for yourself?

AG: I think about this a lot—activism and its role in art—but then I look at my own art practice, and it's not actually that politicized. I was reading an interview with Paul Chan, and he does a lot of directly activist work but also just a lot of "art," and in the interview, he talks about how we shouldn't confuse the two, that we are allowed to maintain an activist practice, and an "art" one—that these don't always have to be combined. There's such a history of that type of conflation (between art and activist), and how effective is it really? It's not that satisfying I think.

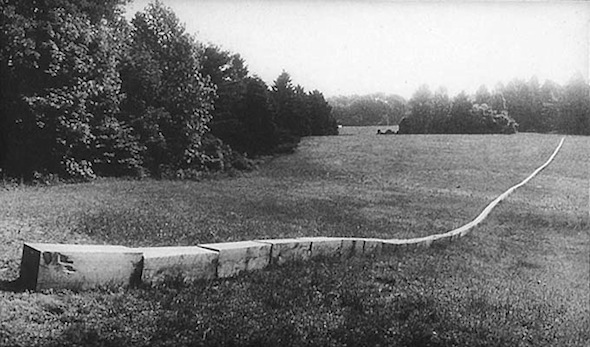

LD: And do you think Rodi Gallery, your mobile van-based gallery, manifests itself as a kind of reaction towards your disinterest in a more standardized gallery context?

AG: Totally. The beautiful part...is that it's a truck, and we can show anywhere—it's not tied down to any gallery or any specific way of working or showing art; it's mobile. I think it's funny that so much has been written about the internet as this emancipatory platform, like it's a new way to show art, and not tied down to any sort of old model of viewership, but it's only done this to a certain extent in the past couple of years. Like, sure people can throw up stuff online and it's free, but some parts still adhere to an older, traditional viewing and distribution model. It's funny to think that even a truck, or an automobile, can be potentially more radical and mobilizing than the internet.

![]()

Rodi Gallery, 2013

Sydney Shen: In some of the writing in Log, your ongoing Google Doc of writing, you express ambivalence towards corporate products like Axe, and their use in artwork. I feel that the use of these materials has been misread as ironic or something, but I'm not interested in hearing about it in ironic or sincere terms, because I don't even know what that means.

AG: I feel when artists use these products it's implied that it's a critique, but it starts getting suspicious when you see the same people using the same type of products—it doesn't come across as critique anymore. I guess also in that Log entry I was reacting against Nick's [Faust] article on the The New Inquiry, its thesis being that the internet has democratized everything and that everyone's on the dance floor, fucking each other on the dance floor, and everything is sort of fair game and open to everyone. It could potentially be true to some degree—the potential of the internet to do that—but when you look around, and see what people are using the internet for and the types of things they are actually grabbing for, it just seems, to me, incredibly limited. Nick cites Axe as an example, and like, what is that doing?

SS: At this point, it's sort of an easy, really loaded icon to latch onto.

AG: I'm hesitant to say that the internet has truly been a catalyst for broadening artistic activity. At the same time, it's done exactly that for me. It's great being able to take whatever picture I want and post it online and then do the same thing again with different objects and materials. Everything is thrown up into the air, like, I can grab and use anything as an art object. In that sense I agree with Nick's essay; I feel like I'm living proof of it. But I don't think it can be claimed that this has happened across the board. It is too sweeping of a statement.

![]()

Floater (Gnocchi), Image, 2013

LD: It's interesting the way you use, "grab" and "thrown up into the air" to describe your process, as these words directly reference the Floater series you made for The Jogging, where you are photographing, just as you described, individual objects being thrown up into the air.

AG: That's actually how I feel. I use the camera so much that eventually when you look around [you realize] everything can be thrown up into the air, like an image or an art object.

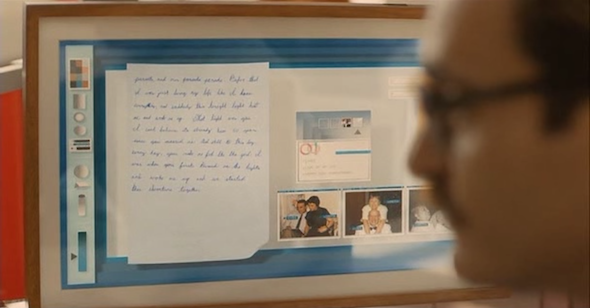

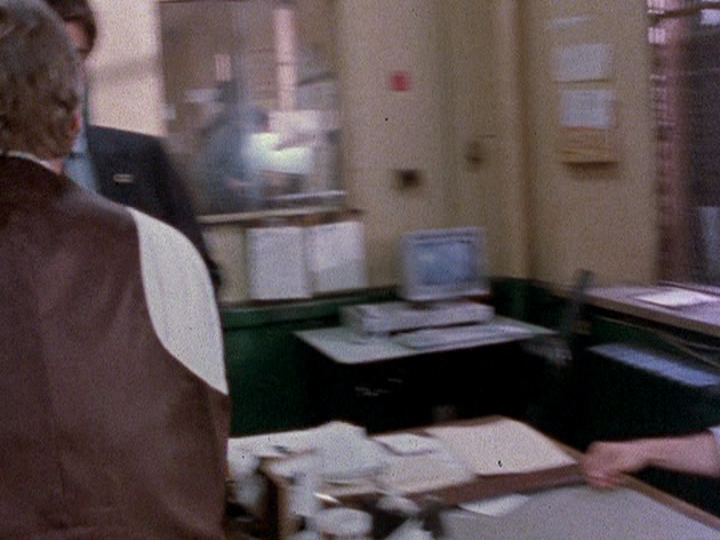

SS: I wanted to ask about your Look At This series, in which you walk around a space with a camera operator, saying "look at this," "look at that" as they pan and zoom to follow your instructions. There's a certain delight for me in realizing what exactly it is you're pointing to, or what you want me to look at. I'm wondering how the camera person or audience knows what to look at. Is it their familiarity with your work, or a certain mode of looking, or how literate the person has to be in photography?

![]()

Still from the Look At This series, 2012

AG: So, the first video I made [in the series] was with Shawn C. Smith, who I did Tanner America with, and generally, just someone who I've been making art with for a while now. The reason I've worked with him so much is because I feel we almost have the same eye, so with that first video, it was an obvious thing. I was essentially like "Hey Shawn, will you come with me? I have this idea. I'm just going to say 'look at this' and you're just going to film it," and since then I've done another one with him. Those are the easiest ones since he's sort of on the same page as me. But of course there has been a range of people at this point, and I always know precisely what I want the camera person to shoot, but at the end of the day it's always a spectrum of what I wanted or didn't want at all.

SS: That's like the failure of Instagram or something. Instagram is almost there, in the way that it's this instantaneous feed of "this is what I'm looking at" and I want people to see it in the way I see it. But, I think the performative method of your series is way more satisfying because it allows for more—

AG: Or I'm a total dictator in a sense. I'm making someone walk around with me, while pointing at stuff, and I'm on the screen; it's like, give me a break. At the same time, I've built in a couple things that are destructive, like the person can shoot whatever they want, they have their own sort of free will.

II

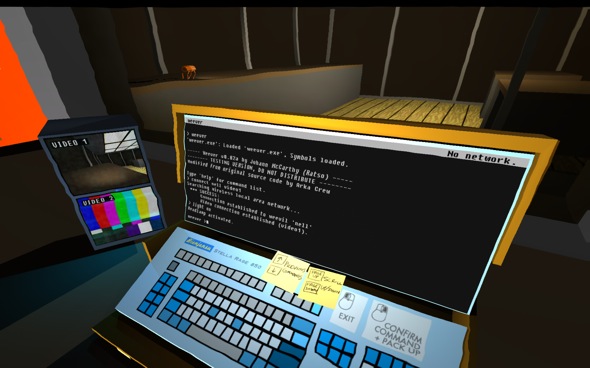

LD: At first, [your fictionalized family Tumblr] Tanner America seemed to me a critique of a certain middle-class American family identity, but in your Log, I found out that your intentions for the project were driven more by an interest in art moments happening outside of the gallery, by participants unknowingly creating art, so to speak.

![]()

Screenshot from "Tanner America" blog, Image, 2010

AG: When you actually look at those who are making images and calling it art online, that pool of people, or content, seems very limited at this point.

I guess I started Tanner by looking at so many images on google for fun. I had been doing these digital collages and was really happy with them, but they weren't connecting with anything, they had no context. They were just nice collages—then I started thinking about where these sourced images were coming from, and realized that most of them were coming from this specific place, i.e. "the family blog." Then I came to this idea and was like, what if I created this narrative out of it? It was obvious to have it be this middle class American family, but it wasn't an intentional critique, it just happened to make the most sense because it was what was happening online; that's where the most exciting images were coming from—the most interesting for me at least. When I think about it now, the subject could have been almost anything, like some old scientist guy in Maine who had a blog with photos, but it just happened to be a family blog. I mean, I obviously picked up on it and ran with it, such as the Tanner AmericaFacebook page, which I suppose has some critique in it, but really it was just a way to generate images and have them make sense. It was a framework for production.

SS: I think that's a nice thing, going back to what we were speaking about earlier, like art as resistance, like you're allowed to be ambivalent in art and you're allowed to simultaneously celebrate and critique something. If anything, art is the space where you should do that, where it's appropriate to not adhere to ideology, or promote one. I also feel like the question "Is this critique or is it not?" is almost like something that moralizes the work from the start, and that almost always flattens things.

But anyways, I thought with Tanner and your other work, you collapse several photographic genres at once. First—as far as traditional genres of photography—there’s the domestic, quotidian, pictures of things in my house, and then there is street photography that's about the moment, the flâneur, and then there's also abstraction; the collages and the wheatpasted bedroom mural pieces are a combination of all of this.

AG: That's something I've been thinking about a lot lately, like what the potential is for rescuing street art. I mean there's a whole history of street interventions, the Situationists for example, so there's a whole history of people doing things in the street, and that's really interesting to me, but it's been sort of—

LD: It's seen as this sort of disgusting activity or genre; you're always a few steps away from Juxtapoz [magazine] or something, so it's interesting that you'd want to give it a new life and identity. It's bold of you, I think.

![]()

Collapse, Image, 2013

AG: Which goes in line with what I was talking about with Rodi. The internet was purported to have exemplified all these egalitarian things, and again, it may have done some of that but it hasn't totally "fixed" everything. I think if we start looking at other methods and technologies like a truck, "street art," or direct action, or start looking in other places, it could be worth our while, because the internet has only gotten us so far.

SS: The street art conversation opens up another topic, something I've been somewhat preoccupied with: delinquency, or the fantasy of delinquency. That's something maybe you also mention a bit in your Log as well. I think I remember a passage that proposes, or rather, encourages the committing of crimes. And I was just thinking about how ever since I was young, staging an elaborate casino heist was my number one fantasy, like I feel what other kids strove for were to become president or go to space, but I just fucking wanted to stage a casino heist. But we can also talk about, for example, how Robert Moses mentions that doing things without permission is sometimes the best way to get things done.

AG: I guess it's also really about artists creating their own self-dependent community and not depending on a gallery system or other venue for showing art.

![]()

It’s Not Paid But, Sculpture, 2013

LD: Sure, yeah I think this is a thought or concern we've all addressed or confronted in our creative lives. And I think you mention it in your Log too; these binaries: do I go off-the-grid completely and start a barter community of sorts, or do I participate speculatively, but compromise certain things. But, you can't and won't go off-the-grid completely. I mean you'll still need that inkjet printer.

AG: You can, but as an artist that's creating and is interested in sharing and communicating with people—the whole point of art is to communicate something; then someone else makes something; then someone sees it—art needs communities in that sense, and I don't know how art could function in an off-the-grid community.

LD: I mean you want to engage with the art world though, you want to get their attention, even with the projects and works you are making in attempts to resist that.

AG: So there definitely is this spectrum of, on one side, this whole professionalized art world and the other is this off-the-grid, barter, hippy, sharing art with each other world, and then there's something in the middle, which is a place I think I currently exist in.

I guess if you think about whatever people are doing, in terms of middle of the spectrum work, there isn't much of it. I just heard about the Voina Art Group, this Russian art group, one of their projects is Pussy Riot—I actually thought they were a real band! I mean they did play and make music but the whole thing was really an off shoot of this Russian art group. I watched a documentary on Pussy Riot recently, and it was such a breakthrough for me, because they're doing all this delinquent or illegal stuff—and it does sort of have this street art stigma—but because of the nature of where they are doing it, in Russia, and that they are being pursued by the government, was sort of exciting for me. Though a lot of it rehashes older art movements and is not necessarily a big breakthrough in terms of the content, one of the things they do say is that they don't show with any gallery, any museum, any sort of festival, etc. They're sort off-the-art-grid which is something that is exciting to me. I guess that this was the question I was asking myself: how to step outside the art model, and it's so hard to think of a way to do that, but when I saw this group I thought it could be one option.

![]()

Print (Tank), Image, 2013

III

SS: How did you become interested in photography?

AG: I took it in high school, but it wasn't really different from anything else…I was just some kid taking it for credit. I got an SLR as a gift my senior year and I just started taking as many images as I could.

SS: Did you bring [your camera] with you everywhere?

AG: Not really, I just started taking a ton of images, and I guess I still do—not from taking pictures myself, but from looking online and using found images.

LD: Photography as just looking—google image searching.

SS: That mindset, that scavenger-hunt mentality. Looking for that moment of affect.

![]()

Screenshot from "Tanner America" blog, Image, 2010

AG: I've always been a visual person before anything else from a young age. I get so much pleasure from looking online and looking for the image that looks so good.

SS: Can you name the criteria for what a "so good" image is?

LD: What does an Aaron Graham google search look like?

AG: The way I did it for the Tanner searches was to put in three random words, any words, and just start scrolling. And there's this certain look—well I was also searching in the large images category—but you can tell when one of them is going to be part of a blog with a lot of other images because it has a certain look where someone is capturing an event, or like when a family has a really nice camera. So I would click on one thing and go to their blog and plow through the whole entire thing....it's like "whoa," it's this intense experience that I just love. I suppose it's pretty voyeuristic, but I never think of it as peering into people's lives, but rather, that this image is killer. There's something very intense about it.

![]()

Floater (Dart), Image, 2013

SS: Maybe this is more of a formal question, but I noticed in almost all of your online works there's a decision to have the pieces on a transparent background with a floating drop shadow. Can you talk about the specific use of that drop shadow?

AG: It just comes from the camera and it happens when you take a flash photograph of something. That crazy drop shadow is so unreal and it separates whatever object you're taking a photo of from that space. It has that feeling of throwing everything up into the air and being left suspended there.

LD: It looks like a photoshoot, like you're treating it as another shot. And the backgrounds are always different, suited to each piece, but they seem to be suitable only for computer viewing, these specific works. You need to scroll down, you need to have it exist within the browser. I guess I'm wondering if you have thought about how you would translate that? So, everything exists as image, but you still are interested in making objects, right?

AG: I am. Everything that I make passes in and out of the camera and computer so many times, so there's not really an endpoint. I can make an object, but it's never resolved. Which has been a really great way of working for me.

SS: I was thinking about the images in your performance/video installation Stage: the juxtaposition of the pianist playing piano with the player piano playing itself. And then there was the artist painting the portrait of the elephant painting, and I'm wondering about the relationship of all those things to the camera.

Stage, 2013

AG: What the camera has done to our idea of an artistic genius really goes back to the camera being a device that is only capable of producing a finite amount of images. Artists can be considered functionaries because each time they take a photograph they are only realizing one photographic possibility which was already contained within the camera. For me, this idea questions where artistic expression and human freedom can occur and whether or not it can exist. There's no stopping a camera, so what do we do? Where do we exist within that? It can be defeating as an artist who is compelled to create images and there's this device that in my mind has created every single one. It's a general feeling of there being so many images out there these days, and as an image maker, you're confronted with what the hell you are going to do.

SS: Do you think that language is a device?

AG: It's the same idea as Borges's Library of Babel, where he says that everything already exists within this library. It was so weird for me to be thinking [through] those questions at Cooper while the school was going to ruin. The ultimate question at Cooper was that, we have this school and this ideal that we value, but it's so hard to articulate why it's worth protecting and saving, and there are these people coming in that want to quantify the experience and put a number value on it, and they think it's possible, but everyone at Cooper [knows] that that would be destructive. So it was the same question in my mind, like the experience of being in the world, and there's this camera that's saying "Here I can quantify that world perfectly" and it's almost impossible [to argue that] you're not capturing everything by taking a photo. Yes, you can charge this amount of money for this education, but there are things that you can't put a number value to.

Aaron Graham is an artist living and working in Yorktown Heights, New York. He graduated with a BFA from Cooper Union in 2012, and is co-founder of Rodi Gallery, a mobile van-based contemporary art gallery. He has most recently exhibited at LODOS Contemporáneo in Mexico City, and has an upcoming show at Welcome Screen in London.

www.aaron-graham.com

Louis Doulas is a writer based in New York City whose research interests are in analytic philosophy of art and philosophy of language. Previously, he was an Editorial Fellow at Rhizome at the New Museum of Contemporary Art, the New York Correspondent at e-flux, and a columnist at DINCA.org. He was also the founder and editor-in-chief of Pool, an online platform and publication critically investigating the relationship between internet culture and contemporary art.

www.louisdoulas.info

Sydney Shen is an NYC-based artist and photographer. Recently she has lectured for Waves of Direction, started a perfume review blog with Laurel Schwulst, written for Gene McHugh's forthcoming book All My Friends At Once, and contributed to Edition MK's Nature of Clouds. She has forthcoming shows in New York and previously has shown in New York, Berlin, Leeds, London, and Montreal. She is also a co-founder and editor of Beauty Today, an annual print magazine that perverts conventions of sexuality and eroticism.

www.sydneyshen.info

.png)