![]()

Ben Aqua, NEVER LOG OFF, 2013 (Limited edition t-shirt designed for #FEELINGS)

We are no longer mostly dealing with information that is transmitted form a source to a receiver, but increasingly also with informational dynamics—that is with the relation between noise and signal, including fluctuations and microvariations, entropic emergences and negentropic emergences, positive feedback and chaotic processes. If there is an informational quality to contemporary culture, then it might be not so much because we exchange more information than before, or even because we buy, sell or copy informational commodities, but because cultural processes are taking on the attributes of information—they are increasingly grasped and conceived in terms of their informational dynamics.

- Tiziana Terranova, Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age

Post internet[1], post media [2], post media aesthetics[3], radicant art[4], dispersion[5], formatting[6], meme art[7], circulationism[8]—all recent terms to describe networked art that does not use the internet as its sole platform, but instead as a crucial nexus around which to research, transmit, assemble, and present data, online and offline. I think all of the writers advancing these terms share a sense that since the rise of mainstream internet culture and social media, art is more fluid, elastic, and dispersed. As Lauren Cornell astutely points out in the recent "Post Internet" roundtable for Frieze, terms are always placeholders for more complex ideas, and when successful, can instigate further, deeper conversation. Towards that end, I'd like to introduce another word to the list—expanded. Drawing from the definition of expansion as "the action or process of spreading out or unfolding; the state of being spread out or unfolded," I consider "expansion" not as an outward movement from a fixed entity, but rather, in light of data's dispersed nature, a continual becoming.[9] Expanded internet art is not viewed as hermetic, but instead as a continuously multiple element that exists within a distributed, networked system. In order to elaborate this term, and to take small steps towards thinking through the changing conditions for art production in the early 21st century, I will use Tiziana Terranova's notion of an "informational milieu" to describe the dynamic process of exchange among artist, artwork, and network.

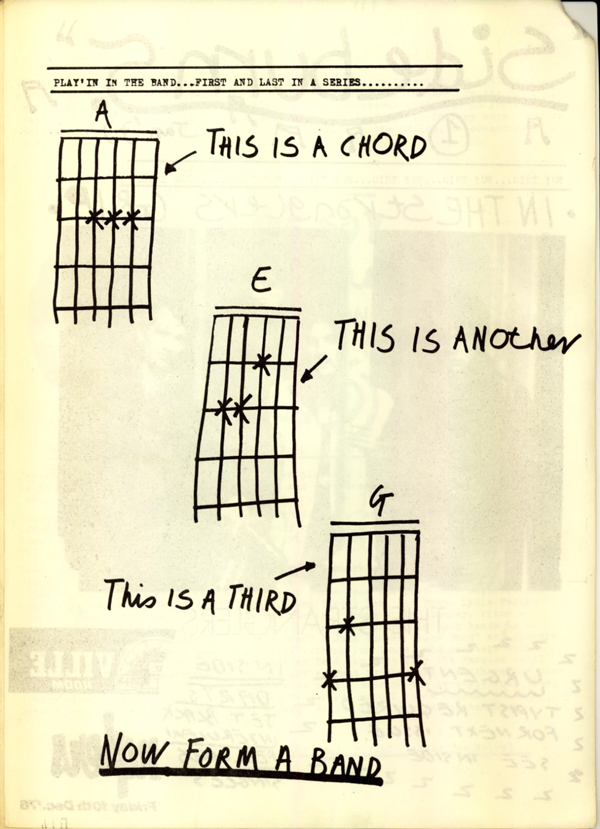

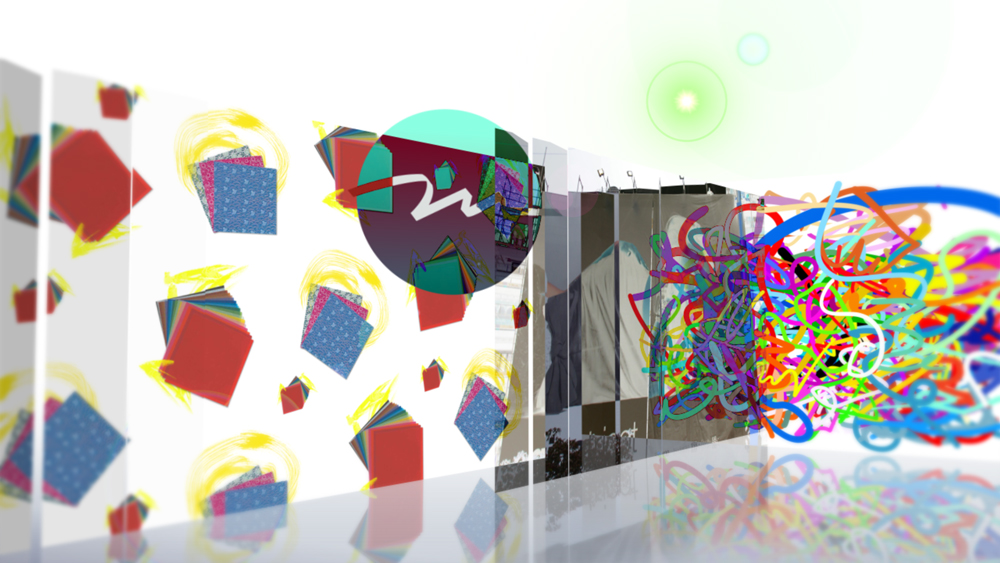

![]()

Harm van den Dorpel, Assemblage ('About' press and reviews), 2012, and Artie Vierkant, Image Object Monday 26 March 2012 10:45AM, 2012 (Installation shot, manipulated by artist Artie Vierkant

In a group exhibition I co-curated with Tim Steer titled MOTION for London's Seventeen Gallery in Spring 2012, we attempted to present and describe artworks that displayed this sort of quality, stating in the accompanying curatorial text:

The object that exists in motion spans different points, relations and existences…it reproduces, travels and accelerates, constantly negotiating the different supports that enable its movement. As it occupies these different spaces and forms it is always reconstituting itself. It doesn't have an autonomous singular existence; it is only ever activated within the network of nodes and channels of transportation…Both a distributed process and an independent occurrence, it is like an expanded object ceaselessly circulating, assembling, and dispersing.[10]

Much like the exhibition's title itself, a sculpture exhibited in the show by artist Harm van den Dorpel from the series Assemblages exemplifies the fluidity and movement of these network-dependent works. Made of Perspex plastic bands tied together in circular forms and suspended in the air by small chains, the Assemblages sculptures resemble tumbleweeds floating in space, a gesture that dramatizes the vast circulation of digital information. The images printed on the bands derive from van den Dorpel's website, which he calls Dissociations. A programmer by training,the artist designed a predictive algorithm to organize the images on the site. Working intuitively, van den Dorpel manually selects groupings of images that the algorithm then learns and replicates.[11] The images themselves include sketches for unrealized artworks, installation shots of completed artworks, and found images. Rather than a standard artist's portfolio organized chronologically, Dissociations forges disparate, atemporal connections among the artist's works and research material, a portrait of van den Dorpel's creative process as well as an ongoing driver for his prints and sculptures. A product of this experiment, visually and conceptually van den Dorpel's Assemblages sculptures express the constant reconstitution and flow of expanded objects.

The key issue in expanded art is not that internet art is on or offline, real or virtual, net or post, but that all art is increasingly embedded within what theorist Tiziana Terranova called an "informational milieu." The capture and transmission of digital information is now a defining characteristic of our environment, a fact that is apparent all around us, in everything from car design to ATM machines. By creating work that is intentionally diffuse and distributed, artists are not just internalizing these conditions, but thematizing them. Expanded internet art is but one demonstration of the art of an informational milieu. But, this is just the beginning. I imagine as our realities, experiences, and stories are increasingly structured by informational dynamics at lighting speeds, art, like life, will morph and mutate accordingly, becoming ever stranger.

In Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age, Terranova develops her term "informational milieu" through a reading of French philosopher Gilbert Simondon's concept of a "milieu." During the advent of cybernetics in the 1940s and 1950s, Simondon described how things emerge in relation to their environs as a type of becoming, one that explicitly presented itself in opposition to the hylomorphic and substantialist tendencies of dominant theories of information, such as the Shannon-Weaver's sender/receiver model of communication.[12] In contrast, Simondon posited that there is no content proper to any elements within a system, and form (as signal) is never abstracted from matter (as noise). For him, information is incessantly engaged in a continual process of exchange within a metastable milieu full of potential energy. Thus, communication always contains the terms of its metastable milieu and can't be abstracted from it. For Terranova, Simondon's ideas are compelling precisely because of his understanding that information is not the content of communication, but an unfolding process within its material constitution. Informational processes exist in the environment in a way that is inherently "immersive, excessive, and dynamic" and that points towards an interpretation of information that is not reduced to mere signal and noise.[13] Terranova's "informational milieu" extrapolates from the processual dynamics within Simondon's model to characterize a moment in which nearly all aspects of human environments exist in ongoing exchange with digital communication, and it asks us to consider how the logic and demands of information's "massless flows" are integral to the reorganization of culture and representation.[14] But we should be reminded that these "massless flows" are not randomly decentralized, rather they are deliberately dispersed according to what Alexander Galloway once described as protocol. (And herein lies the political dimension of art practice today.)

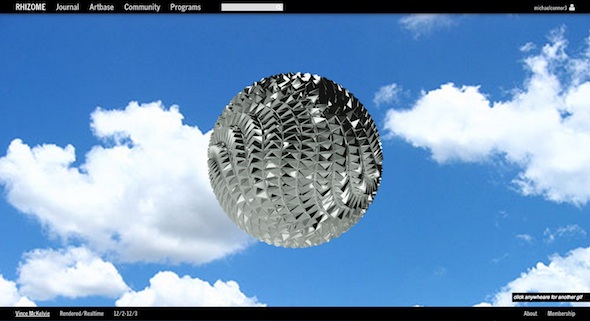

![]()

Kari Altmann, CORE SAMPLES (FLOOR MODELS, DEMOS), 2011 from the series CORE SAMPLES I (2011-Ongoing)

Simondon's push to view form and matter as always already immersed in each other's constitution—rather than as distinct entities—is significant not only for an understanding of information but also for matter. Critic Josephine Bosma picks up on this in her book Nettitudes: Let's Talk Net Art, where she refers to Simondon and thinkers inspired by him, such as Brian Massumi and Gilles Deleuze, to elaborate a non-reductive approach towards matter in an effort to reconsider the role of medium—in other words, material that is employed in an artistic process. Rather than viewing matter, medium, and body as static objects, Bosma reorients the conversation toward an understanding that matter (and, by extension, medium) are constantly in a state of movement and change.[15] Central to her argument is Brian Massumi's definition of matter in Parables for the Virtual as a "form-taking activity immanent to the event of taking form."[16] Matter is not inert, but a potential. Thus, when artists activate all the components that go into an artwork, they participate in what Simondon's termed "resonance" where all elements—matter, technology, body—momentarily sync up with each other. I think of Kari Altmann's practice, where her website acts as an ever expanding database which establishes an equivalency between produced and potential projects, in which all are presented under the header of "content," in many ways mirroring how computers read everything across the board as data. Identifying herself as a "cloud-based artist," Altmann views exhibitions as "another software, another medium that you have to export to."[17] For example, in her series Core Samples I (2011-Ongoing), Altmann acted as a "mutated search algorithm" to aggregate the same orb design across images found online in order to recognize reoccurrences of certain motifs, especially in advertising and stock photography. Core Samples I (2011-Ongoing) has been instantiated as a sculptural "floor model," as videos, and as a blog post for DIS. Altmann's work is very much about the labor of aggregating content, where she constantly compiles and organizes images not only for Core Samples but also across multiple sites like R-U-In?s and Garden Club. By inserting herself into the stream and codifying it according to her own logic, she develops a vision that twists the rapid systemization of information. For Bosma, it is this attuned, intuitive relation to technology that makes artists like Altmann and others so valuable, stating, "…a close 'resonating' with the medium and with technology is a powerful state of being, an awareness of which enables us to also develop responsible or meaningful strategies for an engagement with matter, technology, and the world."[18] Both Bosma and Terranova allow us to think of the artwork as being both within and of informational logic in symbiosis, rather than something that is medium specific or medium determined.

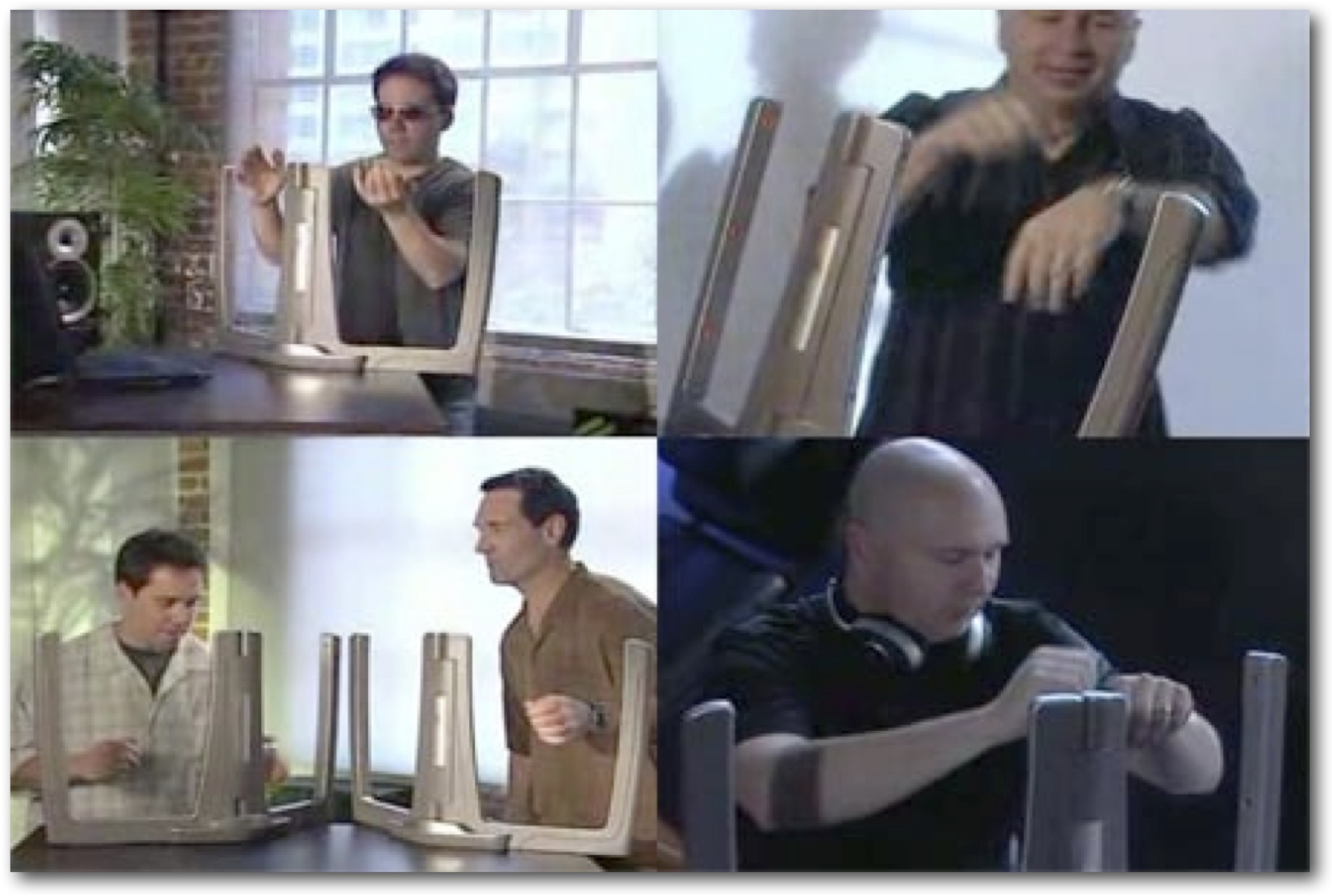

![]()

Brenna Murphy, Lattice~Face Parameter Chant, 2013 (Installation shot)

By being keenly attentive to the dispersion and parcelization of their artworks over a network—allowing them to unfold, surf, drift—contemporary artists are intuitively articulating strategies in ways that resonate with the peculiar way data collection and management are integral to the structure of our contemporary world. For instance, Brenna Murphy envisions her practice—which fluidly encompasses video games, websites, installations, sculptures, prints and performances—as one constant flow, rather than a number of discrete projects. Interested in the way consciousness and the brain respond to digital technology, Murphy operates in tandem with her digital tools in a meditative process to produce repetitive, mind-bending mandala-like structures that play on the viewer's concentration and awareness. Murphy presents these works in contexts both online and off, using digital files as the basis for a 3D print or a video, an installation or a jpeg. Her practice embraces spread, circulation, expansion—artistic production that cleverly and self-consciously takes advantage of its means of transmission and its own existence as data-to virally inhabit any space, every space. Of course, internet art from its inception was expanded to an extent because the structure of the internet itself required it to be in constant circulation, and mutable in form. However, the difference between the 1990s and today is that the internet is much more mobile, more ubiquitous, more mainstream than it has ever been. And it's not just the internet that has changed, we've also witnessed the rise of Big Data as well as an increase in our heavy reliance on software to do everything from navigating our airplanes, stocking our shelves, and delivering our packages. The term "informational milieu" encompasses all of the above.

One of Terranova's key arguments is that an informational milieu radically usurps the production of meaning itself.[19] In her view, traditional perspectival representation assumes a "homogenous space where different subjects can recognize each other when they are different and hence also when they are identical;" the informational milieu puts forth instead an interpretative experience that is "inherently immersive, excessive and dynamic."[20] In light of this, Terranova sees a need for modes of understanding outside of the representational which take into account the "field of displacements, mutations and movement" of informational space. Terranova's point bears on the critical potential of all forms of creative expression under an informational milieu—art, literature, etc. Echoing Michael Connor's recent article "What's Postinternet Got to do with Net Art?", here at Rhizome, it also requires that critics and writers rethink how we read and interpret art. No doubt, we are witnessing widespread epistemological and ontological change in the rise of a deeply informational culture. Art can and does open up concrete possibilities within that space, pushing us forward.

[4]Nicolas Bourriaud, The Radicant (New York: Sternberg Press, 2009)

[7]Michael Sanchez, "2011: Art and Transmission" Artforum (Summer 2013), 295- 301

[9]Oxford English Dictionary Online, s.v. “expansion” “expand”

[11]"I was looking for other ways to reflect an artistic practice online, to replicate a thought process, instead of reducing to the common fixed list of 'selected works' of portfolio sites. For me the art happens between the pieces, less in them, so it was evidence I wanted to develop some new system that would structure this. There are no underlying tags or taxonomies, but it’s 'learning' by 'training.' I get to click choices like 'this thing relates to this, and that one to that,' without 'tags' or other proxies that would force me to interpret with words what things are 'about.' From all these thousands of manual associations it generates these pages, of which some make more sense than others. Sometimes it comes up with surprising combinations; those are small eureka moments for me." Harry Burke "Interview with Harm van den Dorpel," cmdplus (February, 2013) http://www.cmdplus.info/interview/harmvandendorpel.html

[12]See Gilbert Simondon, "The Genesis of the Individual" in Zone 6: Incorporations (New York: Zone Books, 1992). Note, Simondon does name the Shannon-Weaver model explicitly but rather refers to a "technological theory of information." Simondon’s notion of "becoming" was enormously influential for Gilles Deleuze, see Gilles Deleuze "On Gilbert Simondon" in Desert Islands and Other Texts (New York: Semiotext(e), 2004), 86-88 and Difference and Repetition (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995).

[13]Tiziana Terranova, Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age (New York: Pluto Press, 2004), 7.

[14]"…information is not simply the content of a message, or the main form assumed by the commodity in late capitalist economies, but also another name for the increasing visibility and importance of such 'massless flows' as they become the environment within which contemporary culture unfolds. In this sense, we can refer to informational cultures as involving the explicit constitution of an informational milieu – a milieu composed of dynamic and shifting relations between such 'massless flows.'" Ibid., 8.

[15]Josephine Bosma, Nettitudes: Let’s Talk Net Art (Rotterdam: NAi Publishers, 2011), 54.

[18] Josephine Bosma, Nettitudes: Let's Talk Net Art (Rotterdam: NAi Publishers, 2011), 55.

[19] "Information is no longer simply the first level of signification, but the milieu which supports and encloses the production of meaning. There is no meaning, not so much without information but outside of an informational milieu that exceeds and undermines the domain of meaning from all sides." Tiziana Terranova, Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age (New York: Pluto Press, 2004), 9.