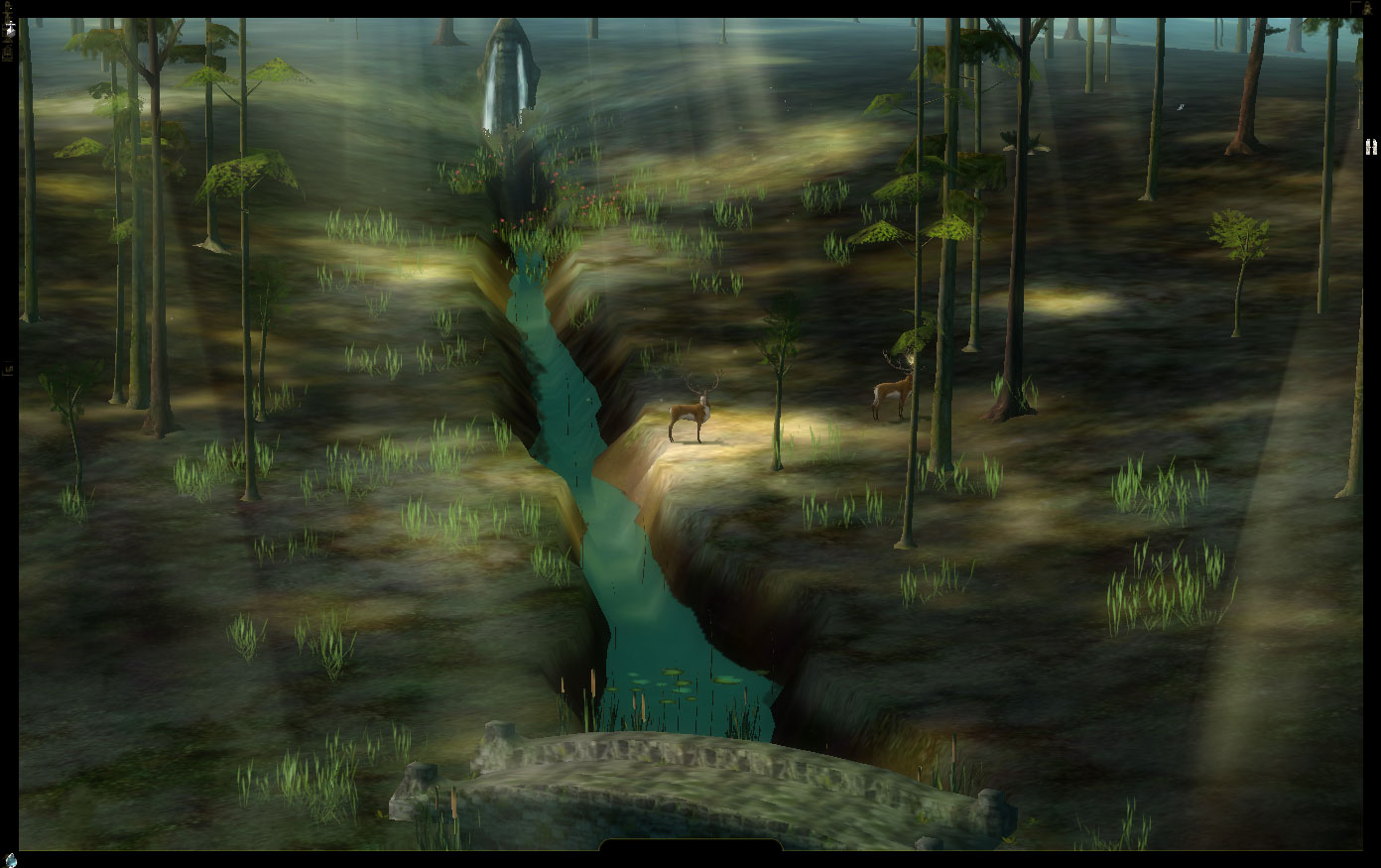

![]() Nate Hill, from the series Trophy Scarves (2013).

Nate Hill, from the series Trophy Scarves (2013).

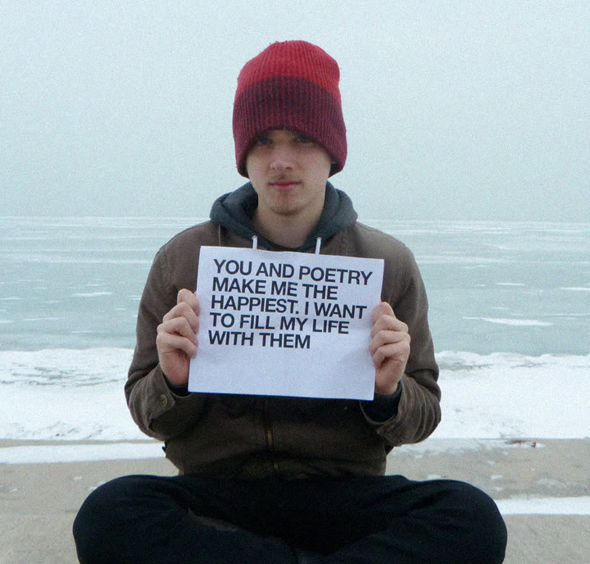

To the extent that people know his name, Nate Hill is a controversial figure in the internet art world. He gets into bizarre, seemingly one-sided fights with art blogs, sends fake computer viruses to his press contact list, or generally puts people off by relentlessly focusing his web projects on "white women"—the most recent example being Trophy Scarves (2013), a photo series in which Hill, who is biracial, poses wearing a tuxedo while nude white women are slung across his shoulders as if they were recently slain wild animals. Like many, I found myself turned off by some of these projects, but, nonetheless, wanted to know more: the satire was clearly there and he was prolific. I also liked how committed he was to being an artist and how thoroughly he followed his artistic voice, no matter where it took him. In a growing series of conversations with Hill, what impressed me was how consistently every project revolves around the idea of a performative "character" and how committed he is to the idea that his artistic voice is channeled through these different characters. I quickly learned that the majority of these characters aren't even internet-based, but performed in public, on the streets and subway cars of New York. Be it online or in New York City, though, these works share a common motivation to be catalysts for disruption, to interrupt Hill's daily passage through networks of various kinds. While I can't justify everything Hill does, after speaking with him regularly and engrossing myself in the work, I am convinced that he is, in a strange way, a significant artist, as well as an interesting if unacknowledged heir to David Hammons and Andy Kaufman, whose projects Hill cherishes. Because he so frequently invokes the idea of character, I thought that to write about Hill necessitated describing him as a character in a fictional style—a mode of prose that I've been experimenting with recently. What follows is an impressionistic story following a few hours in the life of Nate Hill. It precedes two upcoming projects: a live reenactment of Trophy Scarves and "Lights: Nate Hill and Ann Hirsch," a performance event I am curating at Interstate Projects on November 2nd.

Nate stood in the doorway to the East Harlem apartment that he shared with his wife, Alex. He flashed her a big, overly happy smile when she walked up to him and held it in place as though he were posing for a picture. Alex tilted her head a little, observing Nate's face. They shared three seconds of silence, the corners of Nate's mouth feeling sore from stretching. Eventually, she gave him the look—the one with the glasses where she leans in. "What?" he said to her, laughing, "Why are you looking at me like that?"

"Nate…"

"No, seriously, what?" he laughed. There was a redness around the corners of his mouth.

Her eyes tilted to the side. It looked like she might say something, but she just shook her head and instead mumbled something like "You know why…"

Nate said, "What was that? I didn't hear you," and ran his hand over his mouth. Alex shook her head again and said, "I'll see you later, alright?" as she moved to close the front door on him. Nate reached for it, but it was too late. Damn, he thought. Damn damn damn. She just slammed the door on me. She just did that.

He reached into his jeans pocket, but didn't find whatever he was looking for. He thought he heard two people yelling in the street. Or were they laughing? There was a scratch on the door that he hadn’t noticed before. Nate imagined what Alex would say if she was still standing there talking to him—probably something like, I can't live in a fantasy all day like you can, Nate. Something about how she has to get ready for her world, the real world with the stressful day job that allows her to have a savings account and talk with a straight face about the financial implications of parenthood—a topic they'd been actively discussing as the next stage of their lives together. Nate was interested in all of this stuff. He said that to her ten minutes earlier, when they were standing together in the kitchen…of course, he said, he was always happy to talk about any of these issues, but right then, listen, baby, he just…he had to go and do his art—his art…in the subways…he had to go and do that one project where he acts like a bum and tells people conceptual art ideas and then solicits imaginary money which won't pay for anything. Haha. Don't you understand?…It's kind of like a joke about conceptual art, Alex, as, ah, a commodity where, like—okay, New Yorkers would get this, he said to her…because of the art world in New York…and the subways…and the homeless people on the subways…and do you remember how I was telling you about this one artist named David Hammons who did projects like this…and David Hammons was black, Alex, and I'm half black…and…listen, it's art and people will appreciate it someday because it's really, truly good and it's what I want and why don't you want me to have what I want?

At that, Alex slammed her hand on kitchen counter. "I don't want you to have what you want?" she said. "Are you fucking kidding me with that right now, Nate?"

Standing at the front door, he looked at the scratch and wondered how long it had been there. He whispered, "Why don't you want me to have what I want?" one more time so that only he could hear the words. And that was it. He listened to the latch slip to the locked position and he ran his hand over his shaved head and down over his oversized glasses. His neck craned down and he looked at his clothes. There was a stain on his shirt. He felt like his pants were too small for him. He walked down the stairs, opened the door, and hit the street—116th Street; car horns, sun reflecting on garbage bags, hydrants trickling, the spice of halal trucks preparing for the lunch crowd that would arrive in a few hours. He took a breath and closed his eyes and tried to clear his mind. He opened his eyes and realized that it felt good to be on the street, and that after a few seconds he'd nearly forgotten about his problems with Alex; "nearly" because she was still there, in the air, in his world, like architecture you'd never notice but nonetheless feel as a presence.

Nate walked in the direction of the subway station. He lived half a block from the 6, which he took daily to his job as a fly caretaker—yes, he took care of flies that were used in scientific experiments at a medical laboratory off 68th Street. As jobs went, it was pretty decent. It didn't pay a ton (enough to live on reasonably well), but it allowed him to keep his own hours so that during the day he had time to do what he really wanted, which was, like he just told Alex, his art. Although it's not really true that he wants to do his art. A lie, even. It's more that he has to do it. It was only when a project was over and done with that he took any joy from making it.

The stain on Nate’s shirt glistened. From the look of it, it could have been a semen stain, but was, in fact, just cooking oil.His hands squeezed into his pockets and he thought about how he had felt better when he left the apartment building a few moments ago, but now everything seemed terrible. He kept telling himself that. I feel terrible, I feel terrible. Why didn't Alex want him to do what he wanted? I mean, God, what is wrong with her? But here he was supposedly doing it and…He walked to the train and passed some guy in a business suit talking on an iPhone about how "Bloomberg gutted" some other guy, and another guy in a purple FedEx uniform looking depressed and hunched over on his way to work. Nate heard the guy mumbling something in Spanish and then in English, "I'm so hung over yo, but that shit was awesome yo." Nate looked around. Was that guy talking to me? No, he wasn't talking to anyone. He's crazy. Everyone in this city is crazy. Nate looked back to the FedEx guy and realized that he wasn't hunched over and that he didn't even say anything, he was just going about his business like a normal, everyday person—Nate had imagined the whole thing. It wasn't the guy who was crazy, it was him—Nate. He then realized that the thing he had heard about being hung over probably came from his own mouth. Wait, was that possible? I don't speak Spanish and I'm not even hung over. Whatever, he thought. He passed a storefront and saw his reflection. The handsome guy in his mind's eye wasn't there. He was replaced by this nervous-looking tall dude with bad posture. Terrible, Nate repeated in his head, everything's just endlessly terrible. He looked at his reflection again—oh, good, there was that handsome guy again, okay, I knew you were still there. He saw these two kids without shirts cracking up laughing. They were pointing at another kid who was choking and the kid's eyes were watering until he was finally able to hack a peanut shell from his windpipe up into his mouth and out onto the street. The two kids watching him were dying laughing. One of them, Nate noticed, had a chipped tooth. There was a scream in the distance. Probably laughter. A siren blared and stopped, blared and stopped, the guys driving the ambulance were just running red lights.

Nate crossed the street to the downtown subway entrance. He looked around. This part of New York was kind of hard for him to describe. A little south was fancy—the Upper East Side. A little north was more East Harlem proper. Where he was, it was, I don't know, it was just New York. Uptown on the East side. A gentrifying Harlem. Bodegas, places to buy pizza, get your nails done, Duane Reades, Bank of America branches. There were people trudging along on their way through life. Come on, people, wake up and do something, I can't do this all on my own, he had once announced to them all, but no one heard what he said.

Before he headed down the stairs, Nate thought someone screamed again. He couldn't tell if they were laughing. He looked further uptown to see if he could figure out what was happening, but couldn't see anything. Looking up there, he remembered how in this one project he did, he had painted his face white so that it was, like, "white face" and he wore a business suit and carried an umbrella and went into Harlem. The character was called the "White Ambassador," and he would speak up for white people and tell black people not to be racist toward white people, and how his mom was white, and how he resented jokes about how white people smell like wet dogs. It was provocative material and visually intense—the White Ambassador was scary to look at. The art of the piece, though, occurred in the exchange, the dynamic that ensued between Nate's character and the people with whom he interacted. There was a lot going on. A lot of satire and sincerity and joking and boiling anger spilling in too many directions. In another project, he went downtown to the Upper East Side and he dressed up as a McDonald's employee with glasses and his McDonald's uniform tucked into a pair of dark slacks. He rode a bicycle around and threw out free cheeseburgers, singing the McDonald's jingle from the TV commercials—ba, da, ba, I'm lovin' it—and yelling "Free cheeseburgers! Free cheeseburgers!" It was all kind of adorable. The catch was that he had taken a sizeable bite out of each one of the cheeseburgers and wrapped them back up so that people would at first smile and say, "Oh, what a nice young man, so kind to pass out these free cheeseburgers like that," and then they'd open up their cheeseburger and be like "Oh!" So he was a villain. That's what he called it—a "villain." He had a whole series of villains. Heroes, too. Before I had said that the art of the White Ambassador character occurred in the exchange between people, but maybe it's more accurate to say that in all of Nate's work the art occurs on some general level, out in public space as if New York City itself was his artistic medium. The city was, visually speaking, one of the most diverse places in the world and, in turn, his work in New York often probed issues of skin color, asking unsettling questions that hit viewers the way art, as opposed to, say, an essay or a list of stats, can hit someone. He didn't just want to do theatrical performance art. He wanted to do something that he thought of as "real." This city needed him, he thought…or maybe he needed the city. Maybe he needed it to be the city of his fantasies so that he could keep on living here and making art and just keep on going. Or, no, maybe the city needed him. Or, no, maybe he just needed to keep going. Or, no; or, no; or, no.

Nate walked down the stairs to the station. Before he swiped his Metrocard, he noticed there weren't many people on the platform—an indication that he had just missed a train and the next one would be a while. He was caught at the turnstile behind a college-aged kid with a huge purple backpack who was having trouble swiping his card. Even though Nate wasn't in any particular hurry, he almost said to the kid, come on, man, just swipe it; you're not doing it fast enough. Tokens would be better for tourists, he thought. When Nate first moved to New York, you could still use tokens. That was in 2000. He was a different person then. He moved to NY wanting it to be everything that antiseptic Florida wasn't. He wanted the weird, bohemian fantasy that he'd seen in movies and the feeling that you were in a special place—a place that mattered. But it was the Giuliani/Bloomberg era. It was the post-9/11 era. A lot of money. Superficiality. Paranoid security measures. New York seemed more like an uptight, oversold luxury product than a place to live, at least for artists, at least for Nate. So he took it upon himself to be one of those crazy, provocative New York people that he imagined lived here and came up with a whole cast of characters: Bouncy Ride Dolphin, Punch Me Panda, Dropout Man, Wolfie, Death Bear, and the Milkman, not to mention all the stuff on the internet. The Milkman was an interesting one. It was something he performed on an almost daily basis—it was subtle enough to blend in, but if you let it, it could be unnerving. The Milkman wore a white suit, white milkman's hat with black rim, black bow tie and he carried a case of miniature wooden milk bottles. "Milkman, milkman," people would say. They came up to him, inspecting him to make sure that they got that it was indeed a joke costume, and then they grinned and said, "Are you supposed to be a milkman?" And he would look at them with a cutting gaze. He was a half-black man in his early thirties wearing a milkman costume and, the way he looked at you when he wore the costume, something was implied. People were shaken by the fact that it wasn't simply funny and they had to interpret what, if not laughter, it was making them feel.

"Pardon the interruption, ladies and gentlemen…" Nate waded through bodies and an array of annoyed expressions on the downtown 6 train. In the right mood, the frustrated, disquieted cattle shoot atmosphere of the crowded 6 inspired him. People were more primed to be affected by someone causing a ruckus, someone like him, with his subway bum character—"the 6 Train Louse." Before he could get more into his memorized spiel, the car came to a screeching halt in the middle of the tunnel, hurling Nate into a large woman who gave him a dirty look. He made eye contact with her, but avoided her at the same time, almost looking through her. She smelled like she had been dousing herself in perfume. Just as quickly as the train had stopped, it picked up again, hurling him right back into the woman's beefy arms. She raised her handbag and said she'd smack him if he didn't cut it out. He had to get out of there. Get into character, he told himself. So he started over. "Pardon the interruption, ladies and gentlemen. My name is Nate. I'm an artist…" The woman's perfume wasn't letting him think straight. He thought it was settling into the pores of his face. It was overwhelming. He moved further down and took a breath. Alright, better. The rattle of the train gave his words a beat. "For spare change, I can't sing, I can't dance, but what I can do is share some art ideas I had with you today." The screech of the wheels finished his sentence with a flourish. In a mumbled rush, he announced, "Rodeo clowns, one per block, overlooking violent neighborhoods, breaking up fights with their traditional tactics. And, ah, catch a fish in the East River and run it to the Hudson before it dies." And that was it—those were his two ideas. He had hundreds of these little art projects, some of them not-so-good, but many, if not most, kind of great. He looked around at the people on the train. No one paid him attention; he was just another distraction from staring at glossy ads for Monroe College and getting where they had to be. Without missing a beat, he continued, "If you could find it in the kindness of your hearts to give a small, imaginary donation—no real money please, no real money please—for these ideas, it would be greatly appreciated. Thank you." One young guy looked up at him, laughed, and shook his head. "Shit's wack" he said. It pissed Nate off; he pushed through the rest of the car and entered the next one.

He got right back into it: "Pardon the interruption, ladies and gentlemen…" Some people in the second car looked up. He'd seen one or two of them before. Good. That was part of his big idea. He wanted to become a subtly surreal recurring character in peoples' commutes the way that homeless people on the trains and busking musicians can function. By that point, he'd done this character on the 6 train nearly a hundred times.

He told the same art ideas about the rodeo clowns and the fish and then kept doing this for five more cars again and again. A couple more people recognized him. If they were with somebody, they gestured to them. Doing this was therapeutic for Nate in a way—as he got into the rhythm of it and let the cadence of his script interact with the noise of the train and the occasional positive reaction, he felt a knot in his chest that he didn't even know was there loosen a bit. By the time he'd gotten to the 59th Street stop, his delivery had become perkier and he got a few people joking with him, handing him imaginary dollar bills, playing along. He laughed a little and said, "God bless," and left. It felt good to be doing his art. I said earlier that he never enjoyed his art, but that wasn't true. When it was going well, he enjoyed it. He was working to be that guy, the subject of local lore, the one whom people had seen a couple times and then their friend says, "Yeah, I saw him once, too," and then, as Nate's fantasy continued, someone else says, "I saw him before, too, but he was dressed like a milkman." And then they trade more stories about Nate and how he made them think about things and feel things, sometimes unpleasant things, but important things, about race or New York, that they hadn't felt or thought about before. Nate realized then that everything he said to Alex about how this subway piece was conceptual art about conceptual art as a commodity or whatever was bullshit. It wasn't about any of that stuff. It felt good to be so real at that moment. This wasn't for art world people. It wasn't about art. His work wasn't so fucking small minded. Fuck art people. Fuck "art." He did things, he told himself, for the real people out there. His people. Because he was real like them.

"Pardon the interruption, ladies and gentlemen…" Nate began again, feeling really high about himself, but stopped when he noticed an actual old homeless guy in the car holding out a hat, asking for nickels. Nate looked down at his clothes. His pants didn't seem too small anymore. They seemed to fit perfectly. He rubbed his mouth and abruptly stopped doing his bit. At the next stop, he got off and sprinted a few cars ahead so that he wouldn't have to see that old man again. "I'm so full of shit," he said when he walked into the new car. All these people can tell that I'm full of shit. Actually, they couldn't tell anything. They didn't care. He decided not to be in character anymore. It was over. Someone got up and he sat down. Nice. All he wanted was to sit down. The phrase "shit's wack," kept replaying in his head. This subway piece, he thought, should stop soon. I've done it enough, it's not really meant to happen that many times. Besides, it's more interesting in an art context. Nate sat up a little straighter. He felt his spine protest. I mean I'm not just a guy on the street doing a character here, anyone could do that. In this one, I'm connecting it to capital-A art. It's about conceptual art. It's smart and funny. A real breakthrough for me. People will talk about this in the future maybe. In front of him, Nate saw two middle-aged women—tourists from, he thought, Germany, but couldn't be sure. He heard one of them speaking German or what he thought was German and then she said something about "Chris Burden" and "New Museum." Chris Burden, thought Nate. I know that name. Right. Of course, the artist Chris Burden. He shot himself or had himself shot or something. Isn't that right? Nate loved that guy. And the New Museum, that's right, someone he knew had mentioned something about a Chris Burden retrospective at the New Museum. Was that happening right now? Chris Burden, yeah, thought Nate. Guys like him. Vito Acconci, William Pope.L. I'm one of them. I'm part of a tradition. He looked at the people on the train. These people have no idea that I'm part of a great tradition, he thought. Nate looked at the stain on his shirt. He looked at a young woman furiously taking notes. He wished he had his headphones. He just wanted to listen to rap music. He thought about his work being in an art museum and that seemed fun. At the end of the day, his work wasn't about the street, he thought; it's more about art, or…he didn't know. He rubbed the corners of his mouth. One of the German women was staring at him. He made eye contact with her and she kept looking at him like he was on exhibit. He wanted to tell her to stop because it was incredibly rude, but he also took a weird pleasure in it. So fine: he would be the young, black American who was thinking young, black American thoughts. He looked at her again. The eyes of people from Europe were different than Americans' eyes. There was an oldness—not in age, but in a different way. She and her travelling companion got off the train and Nate turned around and looked at his reflection in the subway window. There was, he told himself, an oldness to me, too. Or, at least, I think so. He took a breath and imagined that at that moment he was accepting his destiny as a timeless artist or something. He almost laughed. He knew it was bullshit, but he thought maybe it was true, too. He couldn't tell. Just make your work, Nate, get better, he told himself. That seemed right.

New plan: He was going to get off at Spring and walk over to the New Museum to see the Chris Burden retrospective. Nate imagined his own name in big letters at the New Museum, just like Chris Burden. A career retrospective. With all of his characters and all of his projects on the internet and everything. It would be called "Nate Hill: Heroes and Villains." No, that was too cheesy. He had to be cooler than that if he was going to be a real, serious artist. Well, he'd figure that part out later. He walked up the stairs onto Spring and Lafayette and walked a block in the wrong direction. He always got confused in this part of town. Everything was so expensive. He thought about how it was like twenty dollars to go to the museum and he didn't want to spend that much money. Who would? He passed by a woman who must have been a runway model. He thought about how he didn't even like Chris Burden. That's not true. Actually, he didn't know that much about the guy's work. He was an artist, he was probably good. Nate cracked his knuckles. What do I want? He thought about Alex slamming the kitchen counter when she got mad at him.

Nate went back to the Spring Street station and headed uptown. He didn't do his character or anything; he was just staring at an ad for Apex Technical School. There was a black guy in the ad who was smiling because he had just gotten his degree in Industrial Air Conditioner Repair or something like that and would now be making a real middle-class living. Nate was cracking his knuckles. Someone told him to stop, so he stopped. He got off at 116th Street and went up to his apartment. He looked into the bedroom and the kitchen and said, "Alex?" and he slammed his palm on the kitchen counter. He took out his phone and was about to start writing a text, but stopped. He threw his phone into the sink and a drop of water obscured the screen. It looked like a rainbow. He peered through the mini blinds out onto the street. He thought he heard someone yelling. It was probably laughter.

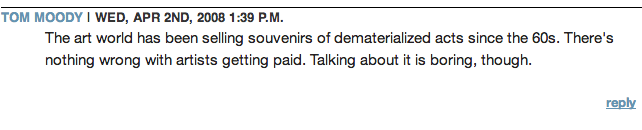

We don't agree with Moody's characterization of digitally-derived objects as "souvenirs"—after all, digital prints and digital celluloid films were produced and circulated widely before it became convenient to display digital works on screens—but we share something of this weariness with having the same Groundhog Day-like conversations. So it's refreshing to think that we may be leaving this conversation behind and entering a strange new one. Instead of championing a field that has been somewhat neglected by collectors, we may now find ourselves addressing new levels of interest in owning technologically-engaged art. If this is the case, our task will be to continue doing what we can to raise consciousness about the history of the field and champion underrecognized and emerging practices within it.

We don't agree with Moody's characterization of digitally-derived objects as "souvenirs"—after all, digital prints and digital celluloid films were produced and circulated widely before it became convenient to display digital works on screens—but we share something of this weariness with having the same Groundhog Day-like conversations. So it's refreshing to think that we may be leaving this conversation behind and entering a strange new one. Instead of championing a field that has been somewhat neglected by collectors, we may now find ourselves addressing new levels of interest in owning technologically-engaged art. If this is the case, our task will be to continue doing what we can to raise consciousness about the history of the field and champion underrecognized and emerging practices within it.

.png)