Rhizome Today

Rhizome Today: A Snackwave History Lesson

Jonas Lund's Paint Your Pizza (2013)

Announcing the 5 Internet Art Microgrants Awardees

Dear Rhizome,

Firstly, thank you for the ride everyone.

Then, a thought: There's something about the whole proposal/open call culture that doesn't feel right for art. When an idea gains too much coherence—and that's what a proposal scheme guides us to create—it's hard to see how it still can be exciting as an artistic gesture.

Bonus tip for future jurors: The decision process gets way more complicated if you end up spying on contestants' social media profiles.

#Winning

Deanna & Jack, Well, Actually: a journal of vernacular criticism!

PDF-based quarterly open to "criticism as it exists in the field, nuance welcomed but not required!" H/t to Brian Droitcour. Edited by Deanna Havas & Jack Kahn.

This has everything I love: the word "actually," an exclamation mark, and a very brief description.

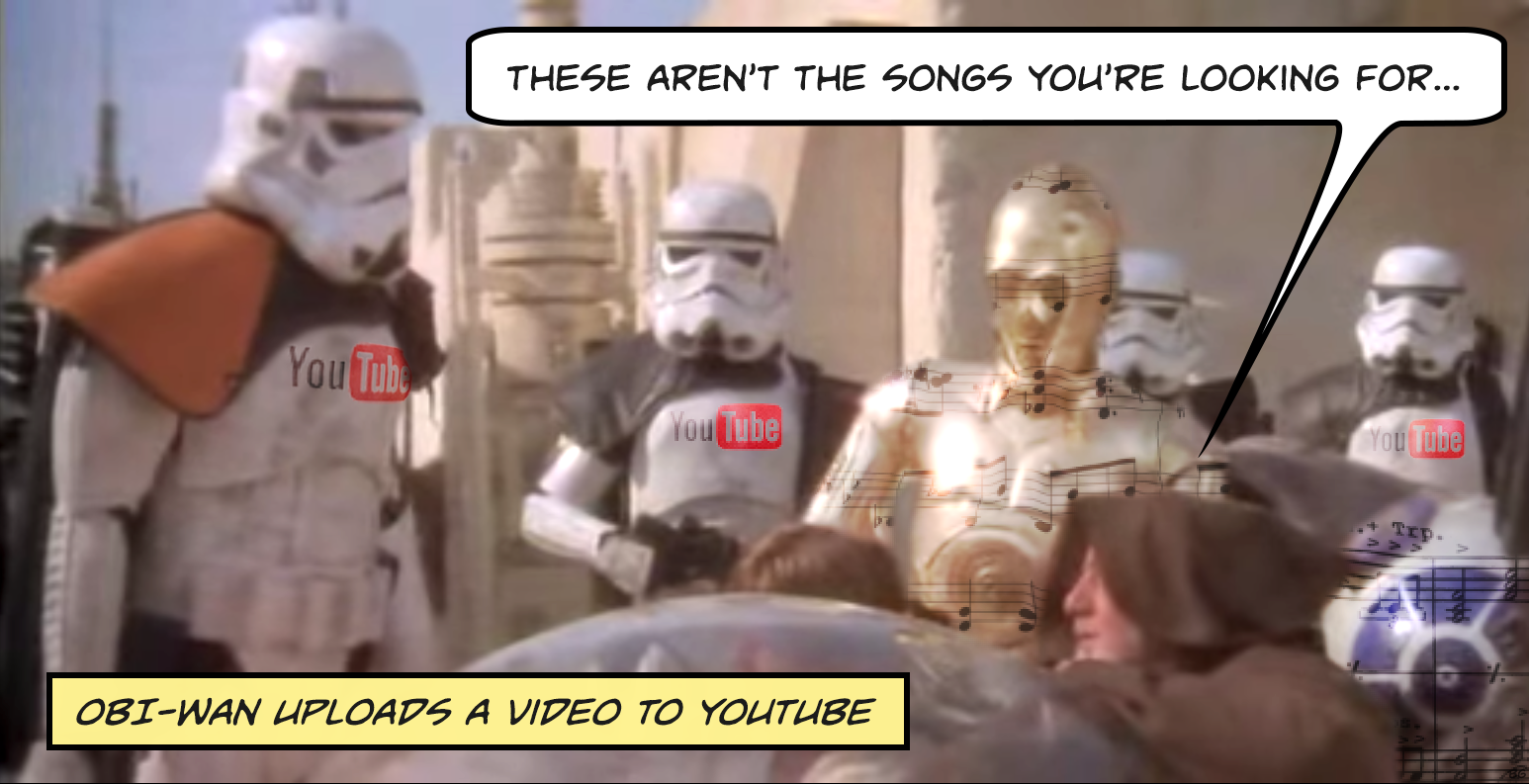

Ben Grosser, Music Obfuscator.

The Music Obfuscator will enable users to hide music from Content ID, the listening algorithms that idenfity copyrighted music on sites like Vimeo and YouTube, flagging every match for automatic muting or removal even in cases of fair use or use with permission.

Actually, this sounds super useful!

Martha Hipley, untitled Twitter hack.

Martha Hipley, untitled Twitter hack.

A proposal to use the Rhizome grant to hire someone to hack two inactive social media accounts so that the artist can have the usernames for herself, thereby unifying her personal brand.

It's like I'm advocating Rhizome to give money to a landlord so she can hire muscle to evict some random tenants.

Lena NW and Julia Kunberger, Viral.

A game that parodies celebrity status games (i.e. Kim Kardashian: Hollywood (app), The Urbz (PS2)) but focuses on the concept of becoming an internet celebrity via social media.

Greetings, I come from Angry Birds land and I want to invest $500 in your crazy-ass game.

Angela Washko, BANGED.

A website for testimonials and reviews by women who have had sex with Roosh V, self-proclaimed pick-up artist and author of BANG: The Pickup Bible as well as Bang Ukraine, Don't Bang Denmark, and Day Bang.

Kinda like three of my fave things combined: Cheaters + 30 Days of Pick-up Art + Heart of Darkness.

Love,

The full shortlist with complete proposals can be found here.

[Thoughts on the open call format, or how the Microgrants might work differently in the future? Let us know in the comments or drop a line to zachary.kaplan@rhizome.org]

Rhizome Today

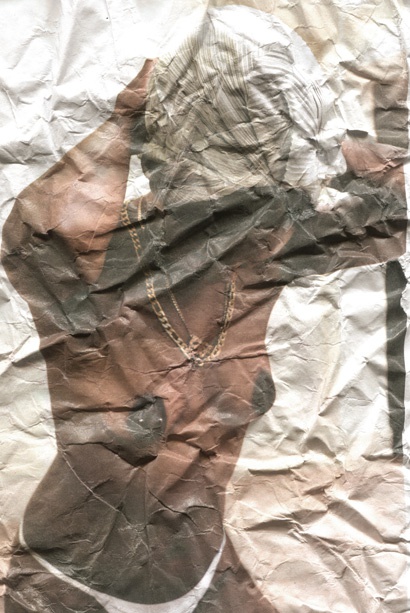

John Akomfrah, Peripeteia, 2012. Image courtesy the artist and Carroll / Fletcher, London.

As Queer Listening: An Interview with Sergei Tcherepnin

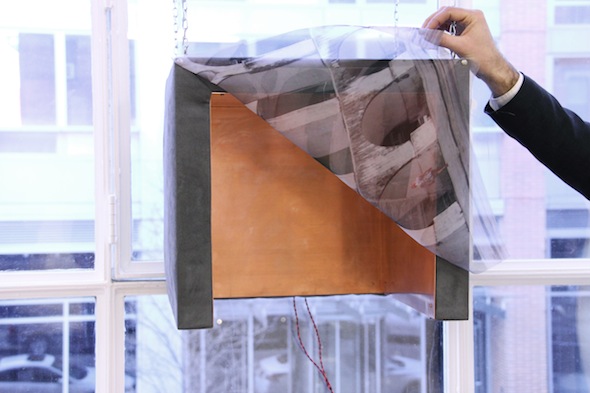

Sergei Tcherepnin, Ear Tone Box (Pied Piper Disappears), 2013. Microsuede, wood, zinc, silk, transducers, amplifier, iPod. Image courtesy Murray Guy. From a poster by Center for Experimental Lectures.

In January 2014, the artist Sergei Tcherepnin participated in a lecture series organized by the Center for Experimental Lectures at Recess. The evening was dedicated to investigating sound as an artistic material, both material and psychological, and also featured philosopher Christoph Cox. While Cox discussed the idea of sound as a pre-linguistic material, Tcherepnin took the opportunity to discuss an aspect of sound practice that remains largely unheard: queer sound and queer listening.

In this dual performance-lecture, "In Search of Queer Sound," Tcherepnin proposed that sound, and the process of listening, exists beyond pure materiality: listening as a social process, one that is not only natural, but also cultural. He suggested that much like linguistic comprehension, our perception of sound is socially coded.

Six months later, I spoke with Tcherepnin to clarify some of the points made during his lecture, to discuss some of his recent exhibitions, and to understand how the concept of queering sound informs his artistic practice, especially as sound continues to rise as an artistic medium and curatorial model.

***

July 31, 2014. Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, NY—Bedford Hills Café.

Charles Eppley: In your presentation for the Center for Experimental Lectures, you described the act of listening as being more than a physiological process, but one that is also socially-learned and culturally constructed. Can you give some context for these terms, queer listening and queer sound? How are they defined?

Sergei Tcherepnin: I started to think about these ideas when I was in college. I was in an electronic music class that was made up of all guys. Later, I was in an analog synth ensemble that was all guys. Electronic music is historically very male-dominated, and there has obviously been a lot of discourse around women and electronic music, and there have been several books written. I started to think about sexuality and this idea of queerness, and separate from music, I was beginning to learn about queer theory.

I started to realize that there was not much conversation on sound, which in reality is very subjective... but normally it is talked about much more objectively. For example, even though a lot of the early 1960s pieces might have subjective tactics or strategies, like liberating the spectator to experience sound differently by walking around the space, there was still always an acceptance of sound as a pure, absolute material.

So, thinking about all of these ideas, I just wanted to question very simply: What would queer sound be? What could that mean?

CE: Is queer sound different than queer listening?

ST: Yes. Listening already implies the subject, whereas sound refers to just the sound itself. I started thinking more about queer sound, something so clearly not defined in terms of orientation, in a way, but then saying, well, what are different orientations of sound? Queer listening is about perspective…

CE: You mentioned that in college you were reading texts that questioned if, for example, there is inherently female sound, or women's sound, and in contrast whether or not there can be sound that is distinctively male or masculine; not so much sounds that assume a subjectivity after being heard, but those that have already attained an identity prior to being heard—a kind of preconditioning. Tara Rodgers published her book, Pink Noises (Duke University Press, 2010), which underscores (and at times challenges) the gender dynamics and politics of electronic music; and of course other articles raise similar questions regarding gendered sound and cultural listening.

Are there parallels between your work and such studies?

ST: I can try to be a little clearer about my approach and how this question enters into conversation with my own work. One of the last projects that I did, In Search of Queer Sound, is a video that I made with my boyfriend, Ei Arakawa, which starts with a question to a call-in talk show, an advice columnist; the questions are always posed by someone with a relationship problem, or something, but always a LGBTQ question. It could be somebody saying that their girlfriend just broke up with them, a teenager whose parents are religious and aren't accepting of them, and what should they do: should they run away from home? They feel like they're in hell. There is another one who is starting to date a guy who is HIV+ and he really likes him, so what should he do? Should he continue dating him or not? There is another guy who wonders about the ethics of gay bareback pornography, which is pornography of gay men having sex without condoms. Each episode of the video starts with one of these questions, and then we have taken out the answers given by the columnist and replaced them with a short answer in sound, or music. This process was a way to re-contextualize the music, which fits in some weird subjective, internal way; the process of subjecting sounds to these questions, inserting them into these conversations, was a way of queering sound for us.

CE: So by juxtaposing the sounds of an otherwise abstract modular synthesizer with these extremely subjective, outspoken calls from LGBTQ persons, this juxtaposition colors the abstract sound—it reorients it in some way?

ST: I don't know how exactly to put it into words, but that process made a ton of sense to us. Whenever I hear these sounds, I think about this man in crisis: thinking about dating a HIV+ man, this fear of HIV, and of infected blood… very subjective things. If that can happen for me as a listener, then maybe it is happening in the work to some degree, for other listeners too?

CE: We are getting into sound ontology, which raises some philosophical questions about what sound actually is. In this discourse there are two leading perspectives: materialistic and linguistic. On the one hand, there is an idea that sound exists prior to any lexicon, language, or ideology: sound as pure material. On the other hand, we also understand sound in relation to language and its interpretation: sound as linguistic. You challenge both perspectives by not actually falling on either side of that debate...

ST: Yeah, that is interesting. I don't think it has to be either/or… the idea that sound is a pure material is one thing I am reacting against, but it's also a given that I am starting with in some way. I think that is why I am in this in-between state—emotionally, psychologically, we are very affected by sound in subjective and irrational ways that we can't explain... the objective sound and the subjective response. We haven't talked much about Maryanne Amacher, but that is what I find so unbelievably beautiful and amazing about her work. She was always so objective in her process, but unbelievably subjective at the exact same time… an uncanny combination of a rational mind and this absolutely irrational decision-making, which came out of just listening.

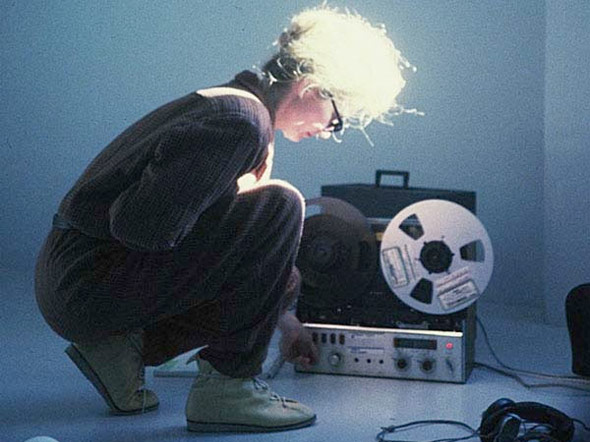

Photograph: Maryanne Amacher by Bryony McIntyre. Audio: Maryanne Amacher, Living Sound, Patent Pending.

CE: You are complicating the materialist/linguistic conversation by engaging this realm, which is psychoacoustics: a subjective response to an objective stimulus, but one that is pre-linguistic… as listeners we can have a sonic experience and our brains process that information in a certain way; it is cerebral, but we do not immediately contextualize or rationalize it. Perhaps this process can be learned, even re-oriented, and maybe this is where we begin approaching queer listening?

ST: Totally.

CE: Can you tell us a bit about your recent exhibition at the MIT List Center in Boston?

ST: The piece is called Subharmonic Lick Thicket. There are a few things going on in the title and the idea of the thicket… I wanted to make a kind of dank, swampy, thickly wooded area, full of sounding objects. The sounding objects are mostly based on tongues—tongue shapes of different sizes—and some are small, about maybe a foot long, and others are up to six feet long. There are probably about twenty tongues total in the room, made out of brass and copper. I wanted to make a kind of thicket out of these things, as if the tongues are growing out of the floor and walls. Some of the tongues are coming directly out of fabric, which is attached to the wall or floor, and some of the tongues and fabrics—mostly silk, chosen because it would look like tree bark, or in some cases animal skin, and also some synthetic fabric—protrude out of mouth-like shapes made of steel, which almost look like clams or Venus fly-traps. They are crude looking, in a way, and have hinged lips that flip up and down. Then there are tongues protruding out of boxes mounted on the wall at different levels: some are knee-high and some are chest-high; they appear to float with tongue-wings… so that gives an idea for how it looks. And then the sound: there is a series of what I call "licks," or short musical riffs—

CE:—like a guitar?

ST: Yeah, but they are all pretty much made on the modular synthesizer that I use—the Serge Modular—and they are playing through these tongues, so the title refers to both the musical material and the form that they take. [The Serge Modular was developed by Sergei's uncle, Serge Tcherepnin, in 1974 —Ed.]

Subharmonic Lick Thicket (2014).

CE: Is there a conscious relationship between the body and these objects?

ST: All of the objects are open to be touched: the boxes can be opened or closed, and the tongues can be bent up and down, but the objects are not simply interactive. In a way, I am trying to figure out how to indicate the fact that they can be interacted with rather than just saying they are interactive.

The sound will sometimes be on in one tongue, or box, but not all of the others, and wherever the sound is happening in the room indicates which work can be changed. You can obviously touch another work, but nothing will happen to the sound, because the sound is not on. I have made a kind of choreography, an orchestration, from one work to another—sometimes two at a time, sometimes four at a time, or sometimes just one—that indicates your movement through the room.

But it is not a necessity to interact with the work: you can just look at the show as you would any other show and hear the sound coming from one corner, while you look at another. But when you do approach a work that is making sound, or music, you can engage with it by really listening for what is happening; and then by touching it, and bending it very subtly, you hear the sound change and come alive. You are enlivening the sound, which might have otherwise been inert, and making it a live object rather than a recorded object. It forms a kind of bond through you, and it is a really intimate and bodily experience because you are touching the work and bringing it to life.

CE: So these brass tongues have transducers on them?

ST: Yeah, the brass and copper tongues all have transducers—actually, not all, because there is one giant, silent tongue that is just an object, or sculpture, and some smaller tongues. But most of them have transducers which turn them into speakers.

A transducer is basically just a speaker, an audio speaker, and you can play any music, for example, from your iPod or computer through a transducer, which basically turns the electronic signal into a vibration. When you touch them to another object, such as cardboard, glass, Styrofoam, or in this case metal—

CE:—or a subway bench…

Sergei Tcherepnin. Motor Matter Bench (2013). Wooden subway bench, transducers, amplifier, HD media player. Unique. Image courtesy Murray Guy, New York.

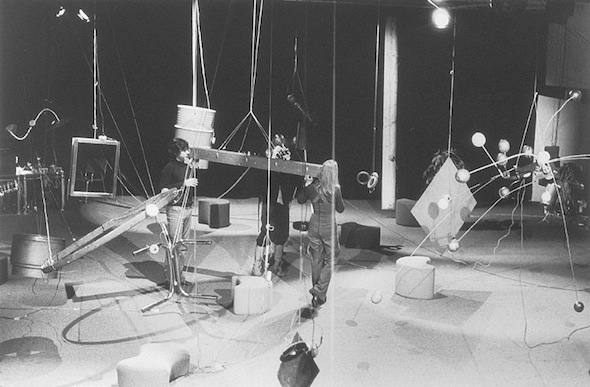

ST:—a subway bench, yes, it turns that object into a speaker. The sound from your iPod or whatever is amplified by the object that you attach a transducer to… on their own, transducers are very quiet and sound something like earphones, but when you touch its surface to another object, its material characteristics—density, thickness, length, weight—filter the sound in various ways. They have been used since the 1960s, at least, in a lot of experimental music—most famously, David Tudor's Rainforest (1968)—and in a way they are ubiquitous in sound art. [In Rainforest, a series of sculptural instruments are "performed" by various musicians who play sound through them via transducers, highlighting the specific resonant properties of each unique object. —Ed.]

CE: When the sound goes through a transducer and is amplified by the tongues, if a person hears the sound and they go up to the newly-minted speaker, which was not a speaker before because it only becomes speaker when a current runs through it—

ST: Yeah, exactly.

CE:—then they can actually manipulate the waveform of the original signal?

ST: The signal is always the same. You are just changing the mouth through which the sound is playing. It is really like in throat singing: when a throat singer sings a tone, and they change their shape of their mouth, they are changing harmonic structure, timbre, and filtration…

CE: Much like a trumpet player using a mute?

ST: Exactly. There are different analogies, but it is really a physical, not electronic, effect that happens to the sound. I think that is really important because the recordings are originally made of analog synthesizer, or sometimes physical actions or instruments, but they are made digital—and then you have these digital files, and when you play them back, they are made into a format; and to make them analog, or live again, is in a way what this work is about. The sounds are animated by these objects.

CE: Would you say they are revitalized somehow?

ST: Yeah. It becomes almost like a live performance every time you listen to the same recorded sound. I mean, that is maybe a dream that I have about it…

CE: Earlier you brought up the relation of this technology to work of David Tudor and the postwar experimental set. David Grubbs just published a book, Records Ruin the Landscape (Duke University Press, 2014), which discusses how some of these artists understood live performance to be un-recordable, in a way, because there was an ephemerality that depended on a spatial and durational context… and so they were resistant to things like audio recording. Similarly, we could never capture a recording of your tongues in action; it would not do them justice because the bodily affect is not preserved. On the one hand, you are working with this idea of sound-as-material, or the materiality of sound, which is a somewhat conservative concept in sound art; on the other hand, there is a representational aspect: Subharmonic Lick Thicket is not just abstract metal sound sculpture. You describe the objects as tongues, human or animal, and the idea of a thicket calls to mind a kind of setting… not a narrative, but rather an environment.

Tudor did something similar in Rainforest, but in that work there are people who perform with the sculptures, and the listeners weren't meant to manipulate his environment. They are able to in yours, and they are encouraged to do so…

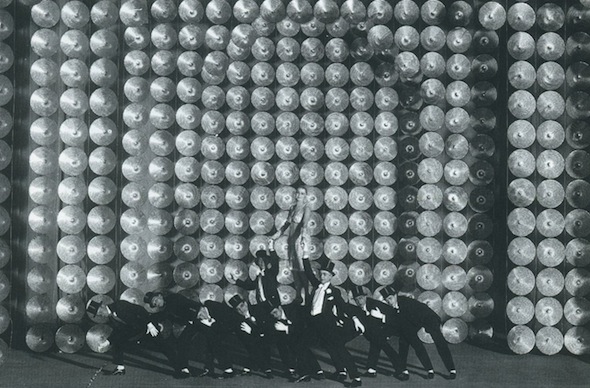

Paul De Marinis (left) in the installation of Rainforest IV (1973), L'Espace Pierre Cardin, Paris. © 1976 Ralph Jones.

ST: This is actually sort of tricky, the way that it relates to Rainforest. There are clear relationships, because Rainforest depends on feedback and the position of the objects in proximity to people and other objects, but I think he chose the title Rainforest because it is an ecosystem, and in a way, for me, the thicket is not a kind of ecosystem because the objects don't depend on each other. They are in conversation as in any exhibition of sculptures, but they are not codependent.

I want to talk more about this idea of interaction, because it is not required—in fact, I am trying to limit it to some degree. I find that when a visitor hears a work is interactive, they expect immediate results. These objects don't give immediate results. They allow you to learn how to listen differently, or change your way of hearing by deeply engaging with the work through touching. There are subtle effects, and the work is not dependent on interaction, but once you do [interact with the work], it brings it to life. In a way, it is a very sensitive work that is much more about intimacy than interactivity: the given is that it is an exhibition of sculptures; the surprise is that, well, you can touch them and get close to them. The way I would like to frame the show… well, there was an article in the Globe that said "this show is interactive" and the first day there were like a hundred people who came in who were literally shaking the boxes when they didn't make any sound: "this is broken, it is not responding to me," and not even listening. I almost had a heart attack because you realize that, in a way, audiences are not really hardwired to be sensitive listeners… Ideas are quickly lost; people leave my exhibition at MIT with huge smiles on their faces, they are having fun, and I am happy about that, but there is a lack of sensitivity. For example, I left the show for a week, and when I came back there were clearly places where people bent the metal to the point that one was completely broken. On the one hand, I am like, "Oh shit, that is vandalism," but on the other I also said, "Bend the metal," so I have to let go of it.

CE: We have been conditioned to act appropriately in galleries and museums, and to act in certain ways—namely, to not touch the art. But now you have these works that can be touched: "Oh, he says we can bend it!" So why not bend it until it breaks? Would you rather them not touch the work at all?

ST: I am bringing in the reins a little, but I am not pretending to make the work about some socialist ideal. Perhaps there are some ideologies built into the work, but what is more important to me is this idea of engaging deeply with listening—engaging the work through listening—and that is completely lost in just bending something until it breaks. Sure, you can do that, but I hope that people would teach themselves in the show, by listening, how to subtly engage the work. In a way, this idea of a thicket reflects this process: as a viewer, you are placed in a kind of foreign, natural environment, and you have to fend for yourself; learn how to deal with it. In a way, it brings out destructive or impatient tendencies, an unintended part of the work. Maybe I am being too pessimistic, and people are shaking things joyously, hearing things that I did not hear myself? This is bringing out my own ideologies and insecurities about the work, but that is good. There are a lot of issues that come up, especially in relation to queer listening, or queer sound. For me, that whole idea is built into a process of changing your perspective in relation to the work, or in relation to what a work can be, and I think that this change of perspective takes concentration, engagement, learning, change. It takes a change of perspective. In order to do that, there need to be some rules built into the work—not that there will ever be a list of things you can or cannot do, but it will have parameters.

CE: Perhaps this illustrates, in some way, a general lack of familiarity with sound work in gallery spaces. What is the reaction to an artist like yourself as sound becomes more prevalent in art institutions, and especially in the gallery context—large museums like MoMA putting on a show like Soundings, or even the 2014 Whitney Biennial, both of which you participated in?

ST: Well, I think that one thing I have realized is that when a curator invites somebody to do something time-based, usually it is video, which is more prevalent than a sound piece, they will know if, you know, it is supposed to be in black and white and there is a figure in green, or if the color is off, they will recognize it; if there is a scene is missing, if there is a corrupt file, they will know something is wrong. Their familiarity with learning a sound piece is so much more abstract, and difficult. I have found that I am often the only person who will recognize if something is wrong, even if it is a small thing, it is big to me. Unless it is something really big, like it turns completely off, but if something gets out of sync, I don't think the curator or attendants will recognize it. So, there is a practical problem, because in my case a piece might run for three months, and I would feel ill at ease to know that nobody there knows what the piece is in its entirety.

That poses a more abstract, or philosophical problem, this unfamiliarity with learning the structures of sound. There is often a lack of differentiation between one and another, where it all sounds the same, and that unfamiliarity poses a problem. It makes it difficult to do an in-depth show about sound, because there is a lack of understanding. I think there is interest, but there needs to be more education, or a desire to learn.

CE: Both of these exhibitions were rather significant moments in the institutionalization of sound art. What was your reaction to these shows? How did they address the issues of exhibiting sound?

ST: Well, for the MoMA show, I showed one object that had a physical presence, as well as a sonic presence, and that was the subway bench with two transducers; for the Whitney Biennial, the piece was more parasitical, in the sense that it used the existing architecture as speakers, using the light fixtures that are used to light the lobby, so it didn't have a physical presence exactly—it was using an existing physical presence as a conduit for sound… both of them were playing with an idea of ambient architecture, and ambient music.

The bench at MoMA was placed at the top of the escalators, and for me having the bench on its own was sort of difficult in this setting. The bench was very popular, and people were basically always sitting on it—but I don't know if that was a product of the work itself or its placement, and the fact that people get tired at museums, and want to sit down. In a way, I don't think it did too much beyond, "Wow, this bench is vibrating, sound playing through my body. Let's move on." It kind of ended at that… I am self-critical about that point.

Installation view of the exhibition Soundings: A Contemporary Score. August 10–November 3, 2013. © 2013 The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

I do think when the bench was in my solo show at Murray Guy, it was extremely effective. It was still an ambient piece, and had the same sound, but it became a place to look at the whole show, and reflect on the show, and with the sound playing through you it completed this thing in a way.

CE: What else was in that show?

ST: There was a video of me as the Pied Piper, in, like, fishnet tights and a miniskirt with a floral pattern, and moving around an urban landscape under an aqueduct, or arcade, in Rio, Brazil. It was kind of like an urban, queer Pied Piper… there were lots of people around that I interacted with, but it was sort of an aimless Pied Piper figure.

Then there was a series of sound pieces: there were two boxes configured so you could sit on a little stool and stick your head inside, and a silk sheer veil that had an image of me as the pied piper that you'd be looking through. Every 10 or 15 minutes there would be what I call an ear-tone pattern, which sounds like two high pitch flutes, in either ear at a pretty high volume. To a visitor who is unaccustomed, they will just hear a lot of beeping coming out of a box... but when you put your head inside the box, I tuned the melodies [into] a pattern, in such a way that the difference tone created in your ear is a constant pedal tone, which is one note. As the two flutes are changing, and if you put your head inside the box, your ear creates a third ear-tone that always stays the same. It is a way of training your ear.

Above: Sergei Tcherepnin, Pied Piper Playing Under the Aqueduct (2013). HD video, 7 minutes. Below: Ear Tone Box (Pied Piper Recedes) (2013). Microsuede, wood, copper, silk, transducers, amplifier, iPod. 16 x 18 x 16 in. Bottom: Detail of Stereo Ear Tone Mirrors (2013). 2 security mirrors, transducers, amplifier, iPod. Each 12 x 12 x 5 in.

CE: You're talking about first order and second order difference tones?

ST: Yeah, so the first order of difference tones would be when you have two pure sine waves, like two flutes, playing one [tone]—say, A, which has a frequency of about 440hz—and then you have a second flute playing slightly higher—say, at 600hz, which is maybe a C—then your ear will create a third tone based on the difference of those two tones. So, literally 600 minus 440, which is 160hz.

This third tone is much lower and created by a distortion in your ear. People describe the phenomenon differently, but I am taking it straight out of a book by Juan Roederer, a physicist who wrote The Physics and Psychophysics of Music (1973).

CE: Is this a neurological or physiological process?

ST: Physiological, actually. First order difference tones are physiological: this is a distortion inside of your ear, in the cochlea. Second order difference tones are neurological: When you have an octave that is slightly mistuned, you feel a beating pattern, which is actually an illusion. That's how Roederer differentiates them.

CE: Which means that second order tones are not actually occurring? The ear does not perceive them through the cochlea?

ST: This is getting kind of technical, but, yeah, it is not that there is actually a distortion in the ear, as in the first order, but rather that the brain is making up this phenomenon, and then perceiving it. That is how binaural beating works when you hear I-dosers, which are sonic drugs, or brain-wave entrainment: you put a tone in one ear, and a second in the other, and then your brain makes up a complex beating pattern, which, when you change the speed cycle, is meant to mimic different brain states: sleep, excitement, whatever. People sell these things online.

CE: This is also a core technique of drone music…

ST: Yeah, for sure, someone like La Monte Young.

CE: And so the Murray Guy show used the first order, where there actually is a physiological distortion in the ear?

ST: Yeah, and, in a way, the boxes were almost meant to be training devices, which were juxtaposed with this queer Pied Piper figure. They really were like flutes, so it became this invitation for music, but [it was] also sort of menacing, because they were high-pitched. I did decibel level readings and they were really not at any volume detrimental to your hearing; it was all psychological.

CE: Noise in general is difficult to talk about in terms of, say, something like noise policy, and noise abatement—since the 1930s, for example, New York City has been combatting urban noise—because that designation is entirely subjective. Maybe this is tangential, but as we are talking about the coloring of sound, these themes seem to be present in your subway bench. Do you think some of this context is stripped when you show it in isolation?

ST: Well, yeah, there were some other pieces too [in the Murray Guy show]: there were subway mirrors that would come on every 30 minutes with an extremely loud difference tone pattern, turning the whole room into an ear-tone box; then there were these three very rusty rain shields that I took off of my apartment and turned into speakers, which were playing a very subtle sound piece through them, which became these speaker-instruments, but also these characters in this urban landscape…so, the bench can definitely work on its own, [because] it did not depend on those other objects, but showing it alone in Soundings did put pressure on the tactile aspects.

For me, the subway is an interesting place; on the subway people have ear-buds, so the bench became an interesting object in relation to how we listen to the world, and especially urban spaces.

CE: Let's talk about the Whitney installation, where you not only attached transducers to very iconic light fixtures, but also in a building that is no longer going to be the main home of the museum. You are using a readymade that is understood in a certain practical, or technological, context (a lamp, a fixture), but also one that is culturally-weighted: an iconic design in an iconic building. So, there is a technological baggage, but also an institutional baggage. How did this piece come together?

ST: Last year I made a piece for Art Basel, a whole booth for Art Statements by Murray Guy, and in it I made a giant piece called Cave In The Shape of an Elevator (2013). The piece was a giant box about ten feet tall with a weird door, as if a rock had fallen in front of it, and the whole box was covered in a blue-grey burlap and thick walls. [You could go] into the box, which could comfortably fit about four people, about the size of a normal elevator, and was lined with different kinds of metal. I printed large photographs of stones on some of the metal, instruments that I used to make the music inside, which [was amplified] through all of the walls. In other pieces, I've made speakers out of chairs, doors, using this kind of ambient architecture or furniture…

I have also thought about past composers dealing with ambient music, like Erik Satie, who made this sort of dry, sarcastic music that played with an idea of "furniture music," which ended up inhabiting a role that he was making fun of: you can now hear the Gymnopédie (1888) in the background of a department store. He went even further in a piece called Rélache (1924), which was a ballet—

CE: Francis Picabia…

ST: Yeah, Picabia did the set, but the music Satie wrote was so unbelievably vulgar to the public at the time, because it was all taken from these popular barracks songs; really, unbelievably bad music. It was this trash of music at the time, and he used it as the main theme of his ballet. So these ideas, like with the elevator, the doors, I wanted to symbolize this idea of background music in the architecture itself: the elevator as a stand-in for elevator music, but as a physicalization of the thing that makes it background; and rather than playing ambient music, I used the ambient structure, and played almost violent, physical music through it, reversing the idea of furniture music, or revenge of the furniture music. When you stepped inside the elevator, the music was very physical, because it was made from stones.

Anyway, Stuart Comer—a curator for the 2014 Biennial—saw this piece in Basel, and we had a long conversation about it, about furniture music, Satie, background music, the Pied Piper… [For me, the Pied Piper] represented the idea of violence against music as functional, a representative of potential for violence, the power of music, and the piper became this sort of queer figure, which ties into what we were talking about in the beginning actually. I talked with Stuart about [these ideas], and a few months later he came to me and said, "You know, have you ever noticed how much the lights in the Whitney lobby resemble the set of Rélache?"

CE: Ah, yes, the backdrop.

Relâche (1924). Ballet by Francis Picabia with music by Erik Satie.

Detail view of Ambient Marcel (Waiting, Working, Erupting), 2014 (E.2014.0114), by Sergei Tcherepnin. Whitney Biennial 2014, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, March 7- \May 25, 2014. Collection of the artist; courtesy Murray Guy, New York. Photograph by Bill Orcutt.

ST: Except instead of a backdrop, they are on the ceiling… It made a lot of sense to me, and it really was perfect. However, I underestimated how insane that lobby is, especially during the biennial, so it was difficult to make a piece that was effective during any time of day. I attempted to make a piece that reflected the different waves of amounts of people, during different times of day. During quiet times of day, there would be subtle, calm music, and during frantic times of day, it would get louder and be more active, as a very basic way to reflect its environment.

CE: How did you get this information? Did you study traffic flow in the museum?

ST: Yeah, but it wasn't anything concrete. I talked to people who work in admissions, and the bookstore, and they gave me times of day that were pretty precise, by the half-hour, which were the most busy, least busy. I made a piece that attempted to reflect that ebb and flow, and it was an ambient music piece, but it was also meant to change, and to have these, I'll say, violent moments that force you to listen, to deal with its presence. I didn't want to torture people, but I did want to have an impact.

I composed my piece during formal hours at the Whitney. I witnessed it with people in the room while I was composing—actually, assembling it, doing the balances—and it was more that the locations of the speakers were spread across the ceiling, which I was thinking about in terms of people. I was not trying to incorporate the sounds of the lobby into the piece necessarily, but recognize that the space was going to be filled with people. I wanted to have the sound enter people's consciousness, and I think sometimes it was very effective: it would be really quiet, and it would be as if, like, there was a little animal up in the ceiling, and I would see people look up, back and forth, and then move around the room. And other times there would be, like, some old lady who would turn to me while I was sitting on the bench, and be like, "What is that awful noise?" That would happen several times, and I had to deal, emotionally, with the fact that a lot of people hate weird, foreign sounds.

CE: Well, aside from a small label that was at the entrance—if you were walking into the lobby, you would not see it until you left—the piece was rather inconspicuous. Maybe people did not know that the work was actually there, until they were leaving, if they recognized it as a work of art at all? That is not a negative thing… actually, I thought it was one of the bolder moves of the show, to give so much room to a piece, so much weight by having it in the lobby, and then have nothing visual on display. I was reminded of Max Neuhaus and his interventions in public space, and how many of his sound installations were also unmarked. Neuhaus was not so concerned that people understand his installations as works of art per se, simply that they have some sort of genuine aesthetic experience.

In the case of your installation, if someone heard its sounds and said, "Oh, what is that awful noise?" then you have still succeeded as an artist, because you have made them think about how their perception of space is informed by sound.

ST: You make me feel better about it! You know, I think that it is a common thing for me, this in-between nature that you were talking about earlier, materiality and linguistics. I didn't want to make a piece that asserted its presence 24/7: the sound object that was living in the ceiling, like this Neuhaus piece, which is a drone that is always coming from a grate underground. I wanted something that would have a nuanced presence, one that was not easily definable. In doing that, I think that I gave up, say, my frustrations about friends going to hear it and saying "Oh, I didn't hear it, maybe it was broken?" I had to come to terms with that to some degree, but on the other hand, maybe there were people who came at 4:45 when it is this period of end-of-day frenzy, where all eight transduced lights are emanating this insane harpsichord swirling pattern, really, really dense. I am sure people heard it—they must have heard it, and ran out of the museum, thinking they were going crazy or something.

CE: Well, you know, in Rélache, there was that moment when all of the lights in the backdrop were switched on, and these fixtures, which faced the audience, formed a wall of mirrored, burning white light that thrust outward. The audience was blinded. I think there are similarities here regarding your approach to re-orienting sound: questions of materiality, linguistics, and the interplay between the physiology and psychology of listening, which seem to be recurring themes in your work…

ST: Exactly. This kind of switchability, a changeability, is good.

_____

Sergei Tcherepnin (b. 1981) is an American artist working in sound, sculpture, video, and other media. Tcherepnin creates sculptural environments and ambient installations that challenge our perception of sound. He has shown his work at MIT List Visual Arts Center, The Museum of Modern Art, Issue Project Room, Audio Visual Arts, Murray Guy, and the 2014 Whitney Biennial. http://murrayguy.com/sergei-tcherepnin/

Charles Eppley is an art historian and sound enthusiast living in Brooklyn, NY. He is a PhD candidate at Stony Brook University, where he researches the history of sound in modern and contemporary art. He works as an art critic and is currently a visiting instructor at Pratt Institute. http://www.charleseppley.com

Announcing the 10 Artists Shortlisted for the Prix Net Art

Rhizome and Beijing-based TASML and CAT/CCIA are proud to announce the artists in competition for the inaugural Prix Net Art. This is a "no-strings attached" $10,000 prize recognizing the past work and future promise of one artist making outstanding work on the internet. A second $5,000 distinction will also be awarded.

The jury—comprising Michael Connor, Rhizome curator; Samantha Culp, curator; Zhang Ga, curator and Director of TASML and Director of CAT / CCIA; and Sabine Himmelsbach, artistic director of HeK (House of Electronic Arts Basel)—considered over 160 nominations for this prize. Internal nominators—Lindsay Howard, Omar Kholeif, Christiane Paul, and Domenico Quaranta—helped to develop a competitive list of candidates.

See the full shortlist below.

Kari Altmann is an artist focused on cultural technology, aggregation, and mistranslation as they relate to all mediums, from images to social networks to sculptures and back again. Her output often exists as new genres and microcultures, which she calls "startups" and "teams", and tracks through her own content management system as they move faster than art product or identity can keep up with. She is one of the most influential artists in the currently titled 'post-internet' canon. Recent features include a solo online exhibition, Soft Mobility Abstracts, for the New Museum, Art Post Internet at Ullens Center in Beijing, and Brands: Concept, Affect, Modularity at Salts Center in Basel, for which her work was a starting point. She has done projects for and with Art Dubai, The Goethe Institute, The New Museum, Fade2Mind, Rhizome, The Hirshhorn Museum, Mixpak, Gentili Apri, Dis Magazine, Nero Magazine, and many more. Learn more.

Cao Fei (b. 1978, Guangzhou) is one of the most significant and innovative young artists to have emerged on the international scene from China. Her multi-media projects explore the lost dreams of the young Chinese generation and their strategies for overcoming and escaping reality. She premiered new work in her September exhibition La Town (2014) at Lombard Freid Gallery, NY. Cao Fei's recent movie Haze and Fog (2013) screened at the Tate Modern, the Art Institute of Chicago, collected by Pompidou Center. Her previous online project RMB CITY (2008-2011) has been exhibited in Deutsche Guggenheim (2010), Shiseido Gallery, Tokyo, Japan (2009), Serpentine Gallery, London (2008), Yokohama Triennale (2008). I. Mirror, 52nd Venice Biennale (2007), Chinese Pavilion; RMB CITY- A Second Life City Planning has been exhibited in Istanbul Biennale (2007); Whose Utopia, TATE Liverpool (2007), She also exhibited video works in Guggenheim Museum (New York), the International Center of Photography (New York), MoMA (New York), P.S.1 (New York), Palais de Tokyo (Paris), Musee d'Art Moderne de la ville de Paris (Paris), Mori Art Museum (Tokyo). Learn more.

Petra Cortright (b. 1986) is a Los Angeles-based artist working in video, painting, and new media. She studied at Parsons The New School for Design in New York and California College of the Arts in San Francisco. Cortright uses a range of media, both digital and analog, to explore the aesthetics and performative cultures of online consumption. Her works, which first gained notoriety in online communities, frequently employs effects, filters, and computer graphics, to highlight performative memes and behaviors common on video sharing sites. In her paintings she approaches the classical subject matter of the figure and landscape with the rapidity and fluidity of the digital tools employed to create them. Cortright's work has been included in numerous group exhibitions including the New Museum in New York, the Venice Biennale, the Biennale de Lyon, and at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. She has had solo exhibitions at Steve Turner Contemporary in Los Angeles, Club Midnight in Berlin, Preteen Gallery in Mexico City, and most recently at MAMA, Rotterdam, and Carl Kostyal, Stockholm. Cortright's work will be shown by the Depart Foundation in Los Angeles in June 2015. Learn more.

Constant Dullaart's work has been featured in the Wall Street Journal, Guardian, Frieze, Art-papers, Dismagazine, Monopol, Rhizome, TAZ and Texte zur Kunst, shown internationally at venues such as the New Museum, MassMoca and UMoca in the United States, Rencontres d'Arles, Autocenter Berlin, the Moscow Polytechnic Museum, and the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. He studied at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie and the Rijksakademie and currently works and lives in Berlin and Amsterdam. Learn more.

jimpunk has participated in various international new media festivals & exhibitions, including : Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), l'espace virtuel du jeu de paume, le SPAMM.fr, 20111 GLI.TC/H festival, Observatori 2008, Dallas video festival, Blip festival, Sonar festival, Rhizome Artbase 101 for New Museum of Contemporary Art, runme.org festival, European Media Art Festival, Stuttgart filmwinter 2009 2005 2004, break21_6th International Festival of Young Emerging Artists, FILE-2002 electronic language international festival, Impakt Festival 2002, machida museum art on the net 2002. Learn more.

JODI, or jodi.org, pioneered Web art in the mid-1990s. Based in The Netherlands, JODI were among the first artists to investigate and subvert conventions of the Internet, computer programs, and video and computer games. Radically disrupting the very language of these systems, including visual aesthetics, interface elements, commands, errors and code. JODI stages extreme digital interventions that destabilize the relationship between computer technology and its users by subverting our expectations about the functionalities and conventions of the systems that we depend upon every day. Their work uses the widest possible variety of media and techniques, from installations, software and websites to performances and exhibitions. JODI's work is featured in most art historical volumes about electronic and media art, is exhibited worldwide in ; Documenta-X, Kassel; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; ZKM, Karlsruhe; ICC, Tokyo; CCA, Glasgow; Guggenheim Museum, NewYork; Centre Pompidou, Paris; Eyebeam, NewY ork; FACT, Liverpool; MOMI, New York, among others. Learn more.

Olia Lialina. Born in Moscow, 1971. Finished Moscow State University as journalist, film critic. Net Artist, one of net.art pioneers. Writes on New Media, Digital Folklore and Vernacular Web. Co-founder of Geocities Research Institute. Professor at Merz Akademie, (New Media Pathway), Stuttgart. Animated Gif Model. Learn more.

Eva and Franco Mattes' practice inhabits the web and skillfully subverts mass media to ultimately expand into and affect the physical space. Their controversial interventions, often bordering on illegality, challenge dominant power structures, including the hierarchical status of the art world, and explore the impact of technology in modern society. Moving beyond the classic understanding of fact and fiction until they become indistinguishable, their actions interweave the "real" and the "virtual" space to create complex open-ended narratives that present a mirror to society, emphasizing the multiplicity of personalities that construct our identity. Learn more.

Ryder Ripps is a 28-year-old conceptual artist and creative director working on the internet in New York. Hashtags in his work include function as form, rigor, humor, authenticity, commerce, pop, platform as form and todays outfit. He began making things on the computer in 1998. In 2009 he created Internet Archaeology – archiving and acknowledging artifacts of the early consumer internet . In 2010 he conceptualized dump.fm, a social network for realtime communication with images – credited as being integral in fostering the current wave of net art. He is the only member of any boy band to have rewritten Ginsberg's Howl. In 2011 he conceptualized creative agency OKFocus, effectuating forward thinking work for clients such as Nike, MOCA, Kenzo, Soylent, Red Bull, Phillips, Atlantic Records, Red Bull, Been Trill and others. He has collaborated with MIA, Ryan Trecartin and Jacob Ciocci. Most recently he has been creating oil paintings derived from digitally warped images of an Instagram model. Learn more.

Rafaël Rozendaal is a visual artist who uses the internet as his canvas. His artistic practice consists of websites, installations, lenticulars, writings and lectures. Spread out over a vast network of domain names, he attracts a large online audience of over 30 million visits per year. He was born in 1980, and lives and works in New York. Learn more.

Rhizome Today

'memed' LimaZulu logo

Contagion! James Hoff's infected media

Music video by Nic Hamilton for James Hoff, Blaster (PAN, 2014).

In 2003, the Blaster Worm was a formidable security breach. A blended threat, rolling bad code into elements of various viruses and worms, it moved swift and ruthless across four hundred thousand Microsoft computers within two weeks.

For his record Blaster, released last month on the Berlin-based label PAN, artist James Hoff used the Blaster computer virus to warp beats from the 808 drum machine into a fungal aural mass.

Disrupting an image, a sound, or a form with "bad data" is a common technique in glitch art: introduce a grain of sand into the system and let it run. But a virus is not just poor data, but malicious code: a language of pointed attack.

Whether that code is genetic or digital, the virus circulates through the population, seeking hosts and propagating itself. In Hoff's own words, in an interview in the most recent BOMB magazine: "[T]raditional illnesses, computer viruses travel through networks of communication or trade, meaning that they can be mapped and rendered graphically across set geographies." A visual representation of the virus' action can be seen on the cover of that issue, in Hoff's artwork Stuxnet No. 2, which was created by infecting a monochromatic image with the eponymous worm to generate a candy-colored, Richter-esque abstraction. Monochromes and readymade beats stand in for human populations and computer networks, allowing the virus' effects to be seen and heard.

James Hoff, Stuxnet No. 2 (2014). Chromaluxe transfer on aluminum. 30 x 24 inches.

Hackers create viruses for crazed fun, for political causes, and to gain new insight into the workings of computer networks. In the latter case, viral infection is a form of play with systems that exposes their vulnerabilities and leads to further reinforcement. The use of a virus to attack the system gives rise to stronger defenses; tension and flux create a more stable whole.

Viruses also spark riots, de-stabilize. Riots in the 1980s, in the cold, blind panic of the AIDS epidemic, infecting the marginalized. Think of Patrick and Sylvester Cowley, of abjection followed by a coherent, cauterizing rage as the psychic reality of disease sets in. Riots in Liberia today, as a new epidemic takes hold against a backdrop of government inaction.

Artist Joseph Nechvatal described the "blending of computational virtual space with ordinary viewable space" as the "viractual realm." Such a blending of corporeal experience and computational space can be seen in Hoff's virus-derived works, and it lends them a certain insidiousness. Each track on Blaster is an immersive, full-body assault, playing on a fear of explosive violence to come, a wall of thick, stabbing noises cloaking and suffocating the listener. The end sensation of these contaminated tracks is intrusion. Infected sounds sharp as a pin, dragged across the paper-thin skin of the eardrum, seeking out the weakest point for entry.

See also:

New book: Digital Contagions by Marisa Olson (article)

Biennale.py by Eva and Franco Mattes (artwork)

Language, a Virus? by Florian Cramer (external link)

Rhizome Today

Chadwick Rantanen solo show at STANDARD(OSLO) in early 2014

Rhizome Today: Incomplete Histories

iGalerie, curated by Claude Closky, Simon Lamunière, Jean-Charles Massera and Benjamin Weil. Designed by Claude Closky.

Rhizome Today: Bruno Latour sur l'herbe

Sunday's NYC climate change march, via @alexmackindolan

Prosthetic Knowledge Picks: The Artist and 3D Printer

The latest in an ongoing series of themed collections of creative projects assembled by Prosthetic Knowledge. This edition continues an exploration of computational sculpture, objects that are shaped by computational processes, beginning with this article on early examples in the field.

Pussykrew, from the series "Unidentified Fabulous Objects."

For anyone with any interest in technology over the past four or five years, the emergence of 3D printing has been unavoidable yet incredibly inspiring, a method of fabrication that has been applied to everything from movie hero costumes to prefab houses.

The term "3D Printing," though, is itself potentially questionable. On appearance the technology resembles plotting machines more than printers (in the traditional sense of the word). Originally, the method was called "additive manufacturing" and defined as "the process of joining materials to make objects from 3D model data, usually layer upon layer, as opposed to subtractive manufacturing methodologies." This means that objects are formed from applying directed material from start to finish as opposed to using an already existing material form and creating a shape by removing from it. The first method of additive manufacturing was invented in 1984 (patented in 1986) by Charles Hull and called "Stereolithography," using ultraviolet light onto liquid photocurable resin (here is a retrotastic short video demonstration). Charles also invented the standard 3D Printing CAD file format STL. Other methods from the 80s include "Fused Deposition Modeling" by Scott Crump, which constructs forms using a controlled jet of filament (the method we are all most familiar with today) and "Selective Laser Sintering" which is similar to Stereolithography in practice but can produce forms in many other materials. Onwards into the 90s, more methods were introduced and businesses specializing in this manufacturing technology emerged. In 1993, MIT claimed a patent for "3 Dimensional Printing techniques" which were subsequently licensed to other companies, and the term has stuck since. Commercial 3D Printing machinery was initially bulky and slow, yet steadily has become faster. It was in 2005, though, that a hobbyist personal market emerged starting with the RepRap project, an open sourced model employing the fused filament model we are familiar with today, and ignited the awareness (and predictable hype) of the technology, able to fit on the future desktop. That isn't to say there are no further innovations in the commercial field—Mcor Technologies have put together a colour 3D printer that use layers of printed and cut paper to create 3D forms (although as you can see in this video, whilst the layering principle is present, the end object requires removal of unnecessary paper material). It does, though, resemble a technique closer to the original definition of printing.

This is an obviously promising area for artistic exploration, yet in many cases, the most widely promoted works in the medium are produced with the sponsorship of printing companies, existing only to demonstrate the technical potential of new tools. These works date quickly as the technology evolves, with new, more detailed and larger outputs, and a wider range of material filaments.

There have been smaller, independent, exhibitions of more compelling 3D printed works: Auru of the Synthetic by Matt Chalker who reproduced miniature examples of familiar contemporary art, and Open Shape, a collection of narrative pieces developed by several artists to be made and sold by the 3D printing company Shapeways.

For this submission, though, I want to focus in particular on artists who apply computational processes to objects, thinking through the translation of data into form via the 3D printing apparatus. These artists avoid the usual algorithmic clichés by exploring and thinking critically about 3D printing as a technical and cultural process.

Marius Watz

Form Studies (Makerbot), (2011)

A Norwegian artist based in New York, Marius Watz' practice is focused on generative coding and abstract computational aesthetics. He has described his process as "parametric modeling," defined as:

The modeling of a form as a system of generative rules, controlled by parameters that describe distinct qualities of that form.

The objects are almost like side effects or artefacts of these processes. Watz was one of the first artists on my radar who was exploring the path of 3D printing and digital fabrication, and is considered an important practitioner in this emerging field.

Probability Lattice (2012).

Modular Lattice (2012).

LIA

Austrian artist who has been creating digital art since 1995 explored the process of 3D printing itself for the project 'Filament Sculptures', a collection of experiments concerned with the behaviour and aesthetics of the filament material itself:

From the project's documentation tumblr:

I am really (!) not interested in creating 3D models in a 3D programme and then simply have them printed out. I rather wanted to know what can be achieved with the actual properties of filament and the movements of the printhead.

So i wrote some short processing application to directly output gCode: This is very basic, because you just define the location of the printhead, the speed of the movement and the amount of filament that should be extruded.

LIA's website; project documentation Tumblr; PK Link.

Matthew Fernandez

Venus of Google (2013).

London based British/ Columbian artist with a focus on technology and the consequences of algorithms, often using the Processing language to code generative form, such as his Disarming Corruptor, a Mac app to encrypt-by-corrupt 3d object files to alter the virtual object form beyond recognition.

Digital Natives

For Digital Natives, Matthew took 3D scans of familiar mundane objects, processed the models and printed the results:

Everyday items such as detergent bottles and a watering can are 3D scanned using a digital camera and subjected to algorithms that distort, abstract and taint them into new primordial vessel forms. In some cases only close inspection reveals traces inherited from their physical predecessors.

Vessels are arguably the lowest common denominator for man-made objects across all cultures, these objects however have no storage function other than to embody the stored digital data that describes them.

For Venus of Google, a female-like form was generated from a single image of a woman which custom code utilized and generated a shape around a simple virtual block, and subsequently printed, a virtually generated form made physical:

The Venus of Google was 'found' via a Google search-by-image, googling a photograph taken of an object I had been handed over in a game of exquisite corpse. The Google search returned visually similar results, one of these being an image of a woman modelling a body-wrap garment. I then used a similar algorithmic image-comparison technique to drive the automated design of a 3D printable object. The 'Hill-Climbing' algorithm starts with a plain box shape and tries thousands of random transformations and comparisons between the shape and the image, eventually mutating towards a form resembling the found image in both shape and colour.

I'm interested in this early era of artificial intelligence, computer vision and algorithmic artefacts, exemplifying the paradox of technology being both advanced and primitive at the same time. This piece investigates the potential use of algorithms to create virtually infinite cultural artefacts.

Here is a video Matthew put together demonstrating the process:

Matthew's website: http://www.plummerfernandez.com/

Matthew's #algopop tumblr: http://algopop.tumblr.com/

SolarSinter Project

This is probably the most creative and poetic 3D printing method that has been put together: a project from 2011 by Markus Keyser utilizes magnified solar power and sand as material to create glass objects. Here is a video of the computer-controlled machine being used in the Morrocan Desert.

And from the project description:

In the deserts of the world two elements dominate—sun and sand. The former offers a vast energy source of huge potential, the latter an almost unlimited supply of silica in the form of quartz. The experience of working in the desert with the Sun-Cutter led me directly to the idea of a new machine that could bring together these two elements. Silicia sand when heated to melting point and allowed to cool solidifies as glass. This process of converting a powdery substance via a heating process into a solid form is known as sintering and has in recent years become a central process in design prototyping known as 3D printing or SLS (selective laser sintering). These 3D printers use laser technology to create very precise 3D objects from a variety of powdered plastics, resins and metals—the objects being the exact physical counterparts of the computer-drawn 3D designs inputted by the designer. By using the sun's rays instead of a laser and sand instead of resins, I had the basis of an entirely new solar-powered machine and production process for making glass objects that taps into the abundant supplies of sun and sand to be found in the deserts of the world.

More here.

Pussykrew

Polish couple Andrzej Wojtas and Ewelina Aleksandrowicz have worked in various digital forms such as motion and animation. Inspired by net art aesthetics, the duo invested in a 3D printer to bring a fluid, gender-bending style into physical reality. Initial models were shown to be constructed with a 3D printer with a live video stream and documented on their Unidentified Fabulous Objects Tumblr. Their efforts were recently exhibited at the London 3D Printshow, and won the art category.

Ashley Zelinskie

Reverse Abstraction

One and One Chair

Brooklyn-based artist, now in residence at NEW INC, whose works focus on the interplay between language and computer technology. In her Reverse Abstractions series, 3D volumes such as cubes and chairs are formed from a rigid skin of densely packed alphanumeric characters. This is not a cosmetic touch—the characters are the hexadecimal values of the 3D object files they represent; thus, these are objects which both people and computers can understand:

… humans and computers perceive the world through different languages, and what is concrete for one is abstract for the other. The objects and shapes so familiar in human art can be neither perceived nor conceived by computers in their original form. Likewise, the codes that are so familiar to a computer are merely scattered symbols to human sensibility. The Reverse Abstraction series attempts to bridge the gap by constructing traditional objects in dual forms: as the classical object and as the hexadecimal and binary codes that represent them. Thus, abstraction becomes material, the meanings for humans and computers are united, and the duality is resolved.

Ashley's website: http://www.ashleyzelinskie.com. A large-scale laser-cut cube from the Reverse Abstractions series was recently acquired by the US State Department for installation in the US Consulate in Jeddah, now under construction, no doubt because of its visual resonance with the Kaaba.

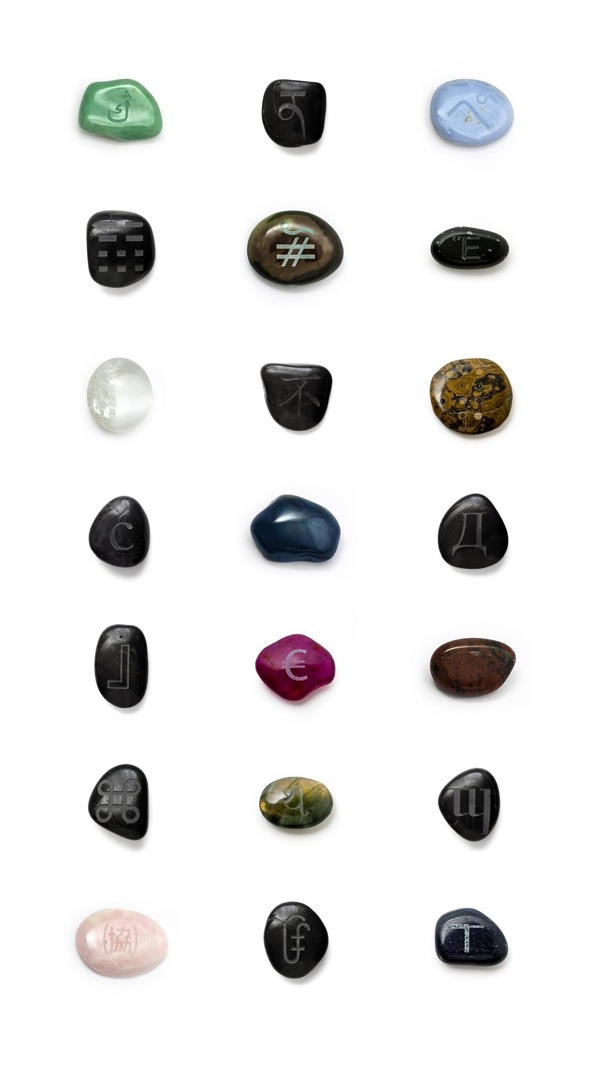

Morehshin Allahyari

Iranian artist now based in the US created the "Dark Matter" series of printed artifacts designed with 3D software that combine surreal and humorous object combinations. These objects individually are either banned or frowned upon in Iran. Weird and nonsensical yet politically motivated, the project highlights the potential for computational sculpture to create and transform cultural archives. To some, owning a 3D printer could be considered a political act:

"Dark Matter" is a series of combined, sculptural objects modeled in Maya and 3D printed to form humorous juxtapositions.; The objects chosen for the first series are the objects/things that are forbidden or un-welcome in Iran by the government. The objects that in many other countries people use or own freely but under Iranian government laws (for several reasons) are forbidden or discouraged to use. Owning some of these objects/things (dog, dildo, gun, neck tie, satellite dish, etc.) means going to jail, or getting a fine, or constantly being under the risk of getting arrested or bothered by the moral police. By printing and bringing the virtual 3D into physical existence, I want tosimultaneously resist and bring awareness about the power that constantly threatens,discourages, and actively works against the ownership of these items in Iran. No matterhow functional, through 3D printing, I am able to re-create and archive a collection offorbidden objects. In a way, the sculptural objects serve as a documentation of lives (my own life included) lived under oppressions and dictatorship. This is the documentation of a history full of red lines drawn in the most private aspect of one's life.

Project webpage; step-by-step guide to the method on Instructables.

Jonathan Keep

Icebergs

Seeds

Random Growth

Sound Surface

British artist Jonathan Keep has put together a method of 3D printing objects using a more traditional art material—clay. Working in sculpture for more than 20 years, the 3D printer (and computer) has extended his range of creative development. Various projects has seen vases made of sound data and random outputs based on natural computational processes, subsequently fired and glazed:

I have long used computer software to develop new ceramic forms. With an interest in the hidden numerical code that underpins all nature I have developed a working process whereby the shapes of these pots are written in computer code. This digital information is passed to a studio based DIY 3D printer that I have adapted to print in clay. Layer by layer the pots are printed out – a sort of mechanical pottery coil building. After printing, the ceramic is fired and glaze in the normal way.

From the elemental forces of earth, fire and water pottery has traditionally drawn on nature for inspiration. In using computer code to create this work I aim to add a further layer to include the elemental, naturalmathematical patterns and structures that underlie all form. The appreciation of this work illustrates just how much we are connected at a very deep level to the natural world.

Jonathan's portfolio of digital pots.

See also: Two projects that convert music into 3D meshes for 3D printing, Sonic Prints and Microsonic Landscapes.

Gokinjo Monozukuri

And finally… Japanese collaborative artists Gokinjo Monozukuri (made up of Nukeme, Kanno and yang02) together work on projects exploring creative potential with 3D software and photogrammetry (the method of constructing 3D objects with a collection of photographs taken at various angles.) One such project is the fashion focused Computer Copy where a garment is worn and captured, reduced to a smaller polygon count, and reconstructed with digital fabric prints. Another project, Captured Desire, aimed to reconstruct portraits of famous personalities using various photos on Google Image:

There is a web service which makes 3D models using the pictures taken from various angles. The aim of making "Captured Desire" is printing full colored 3D model by collecting similar uploaded images on the internet instead of taking pictures by ourselves. The more attention the subjects gather, the more images are uploaded on the internet with the result of higher resolution of the 3D models.

These days, a lot of 3D cameras and softwares are developed, and we expect that everything in the world will be 3D modeled with high resolution in the near future. The method of our work is kind of cloud-sourcing and suggests a new way of 3D modeling at the moment in which the 3D system is not fully grown. Therefore, our printed 3D models are distorted and don't have the back side. But we can say that this is a sampling of the present moment of technology which progresses rapidly. Our models will also express the desires of the people living in the present day by showing the amount of popular images and the number of access counts.

Rhizome in London: "Do You Follow? Art in Circulation" at The Old Selfridges Hotel

October 15, 2014 - October 17, 2014

A series of afternoon talks as part of the ICA's Frieze-week program at The Old Selfridges Hotel in London.

Featuring Kari Altmann, Alex Bacon, Hannah Black, Michael Connor, Constant Dullaart, Renzo Martens, Monira Al Qadiri (GCC), Takeshi Shiomitsu, Martine Syms, Christopher Kulendran Thomas, and Amalia Ulman.

Amalia's Instagram – 10th July 2014.

With the screen arguably now the primary site of encounter for contemporary art, this talks series, taking place as part of ICA Off-Site: The Old Selfridges Hotel, examines the ways in which internet circulation has affected art practice and art's function.

Do You Follow? Art in Circulation begins with the premise that images do not merely depict their surrounding reality, but actively produce and shape it in economic, social, and physical ways. With the advent of the internet, the image's power to effect such transformation has greatly expanded. As a result, image production is by default a posthuman process, subject to the demands of global flows. Images circulating on a network may produce far-flung realities, in unpredictable ways. Some even claim that the world is becoming an image.

Building on last year's Post-Net Aesthetics panel, this series continues the conversation about art under a networked condition, exploring possible artistic positions in response to three particular aspects of this condition: the internet's tendency to turn artworks into pure image-commodities, to turn locations into image-places, and bodies into image-bodies. How can artists participate in the reshaping of the world by posthuman images and find political possibilities and expansive subjectivities within this process?

Wednesday Oct 15, 3:30pm

"Internet circulation has made all art look the same"

Martine Syms, For Nights Like This One, 1979, 2014.

"Why does so much new abstraction look the same?" asked critic Jerry Saltz in New York magazine earlier this year. Galleries, he lamented, have gone over to "copycat mediocrity and mechanical art," coming to resemble the generic look of shopping outlets rather than the "individual arks" of the past. In particular, Saltz criticised the influence wielded by "speculator-collectors," which many understood to refer to art world figures who use social media channels such as Instagram to generate attention for their favoured artists.

On this panel, art historian Alex Bacon challenges Saltz' contention, suggesting instead that we are not looking carefully enough. Artists Martine Syms, Takeshi Shiomitsu, and Kari Altmann discuss the role that internet feeds play in their practice, arguing for different understandings of the problems and potential of "sameness" in art. Chaired by Rhizome Curator/Editor Michael Connor.

Thursday Oct 16, 3:30pm

"Internet circulation changes places into image-places"

Renzo Martens, Episode III: Enjoy Poverty, 2008

There is often a gap between what images do and what they say they do. When we talk about images, we often discuss their content or message or our experience of them. Beyond the question of impact on the spectator, though, images act on the world in fundamental ways. Renzo Marten's film Episode III: Enjoy Poverty (2008) for example, documented his efforts in the Congo to establish ways for local people to profit from images of their lives. With its injunctive title, Martens' starting point was that the content of images produced by well-meaning foreign photographers was less important than their effect, which was (in part) to earn money for those photo-journalists.

Through the work of four artists who deal with very different locations, this panel considers how places circulate as images, how this circulation shapes such places, and how artists can participate (or not) in such transformations.

Speakers include artists Constant Dullaart, Renzo Martens, Monira Al Qadiri (GCC), and Christopher Kulendran Thomas.

Friday Oct 17, 3:30pm

"Internet circulation changes bodies into image-bodies"

Amalia Ulman

A selfie is not a portrait, critic Brian Droitcour has argued, because unlike a portrait, which inscribes the sitter in history, it inscribes the body of its subject/maker into a network. This panel continues this line of reasoning, positing that the process of inscribing bodies into networks allows them to circulate as images. To borrow a term from artist Andrea Crespo, our image-bodies morph, interact with one another, spark strong attachments with human viewers, and ultimately effect transformations on our physical bodies in ways that may be oppressive, liberatory, or both.

This panel will include a presentation by artist Amalia Ulman, who for her online performance Excellences and Perfections (2014) used her social media accounts to circulate images depicting her body undergoing a surgical and cosmetic transformation. It also features artist and writer Hannah Black, whose work has dealt with bodies as vessels, the theorisation of the "Hot Babe," and (most recently) the abolition of the body.

Work from Amalia Ulman's Excellences and Perfections will be presented beginning October 20 as part of First Look, the online exhibition series jointly curated by Rhizome and the New Museum.

In collaboration with:

Rhizome Today

Still from Nicole Miller, Jump to the Crescendo, 2014

Index of Rhizome Today for August

Rhizome Today is an experiment in ephemeral blogging: posts written and published each morning, and unpublished within a day. The latest post can always be found at http://www.rhizome.org/today.

After some discussion about the best way to wrap up each month's posts, we've decided to publish a list of topics and people covered on Today during the preceding month. Here is the index for Rhizome Today in August, 2014.

Topics

- Amazon (8-Aug, 11-Aug, 26-Aug)

- ARE.NA (20-Aug)

- Bomb Iraq (26-Aug)

- Chat (5-Aug, 6-Aug, 7-Aug, 8-Aug, 12-Aug)

- Computer animation (13-Aug, 25-Aug)

- Depression Quest (19-Aug, 20-Aug)

- Drones (4-Aug)

- Facebook (5-Aug, 11-Aug, 12-Aug, 22-Aug, 27-Aug)

- Ferguson (13-Aug, 14-Aug, 15-Aug, 19-Aug)

- Forensis (HKW Exhibition) (15-Aug)

- Fuck Everything (video game/dating sim) (19-Aug, 20-Aug)

- GIFs (1-Aug, 20-Aug, 25-Aug)

- Helmet cams (15-Aug)

- Instagram (4-Aug, 11-Aug, 12-Aug, 22-Aug, 27-Aug)

- Kickstarter (4-Aug, 29-Aug)

- Labor (15-Aug, 29-Aug)

- Mail Art (19-Aug)

- MS Paint (6-Aug)

- Poetry (1-Aug, 7-Aug)

- The sharing economy (7-Aug, 15-Aug, 26-Aug)

- Snapchat (12-Aug)

- Social Media (4-Aug, 5-Aug, 6-Aug, 7-Aug, 11-Aug, 12-Aug, 13-Aug, 14-Aug,15-Aug, 19-Aug, 20-Aug,21-Aug, 22-Aug, 26-Aug, 27-Aug, 28-Aug, 29-Aug)

- The feed (5-Aug, 12-Aug, 21-Aug, 22-Aug)

- Twitter (4-Aug, 5-Aug, 7-Aug, 11-Aug, 12-Aug, 13-Aug, 14-Aug, 15-Aug, 19-Aug, 20-Aug,21-Aug, 26-Aug,28-Aug,29-Aug)

- Video (4-Aug (video of a drone), 5-Aug, 8-Aug (iMovie), 12-Aug, 13-Aug, 14-Aug, 15-Aug, 20-Aug, 21-Aug, 26-Aug, 27-Aug)

- Video games (13-Aug, 19-Aug, 20-Aug, 26-Aug)

- VSCO Cam (27-Aug)

- Wikipedia (6-Aug, 12-Aug, 28-Aug)

People

- Amalia Ulman (15-Aug)

- Andrea Crespo (28-Aug, 29-Aug)

- Andrew Cannon (25-Aug)

- Ann Hirsch (19-Aug)

- Bunny Rogers (12-Aug)

- Christoph Schlingensief (4-Aug)

- Micaël Reynaud (1-Aug)

- Cory Arcangel (11-Aug)

- Dan Phiffer (26-Aug)

- Dragan Espenschied (1-Aug, 4-Aug, 11-Aug, 26-Aug)

- Dread Scott (14-Aug)

- Emilie Gervais (28-Aug)

- Erica Love (29-Aug

- Eteam (4-Aug)

- Eva and Franco Mattes (28-Aug, 29-Aug)

- Faith Holland (29-Aug)

- Frances Stark (4-Aug, 7-Aug, 8-Aug)

- Gabby Cepeda (29-Aug)

- GCC (4-Aug)

- Harry Burke (7-Aug, 15-Aug)

- Jasper Spicero (12-Aug)

- Jennifer Chan (13-Aug)

- Jesse Darling (5-Aug)

- João Enxuto (29-Aug)

- Joel Holmberg (1-Aug)

- Keith J. Varadi (5-Aug)

- Kevin Bewersdorf (1-Aug)

- Kimmo Modig (5-Aug)

- Lena NW (19-Aug, 20-Aug)

- Loney Abrams (5-Aug)

- Lu Yang (13-Aug)

- Lucy Chinen (15-Aug)

- Martha Hipley (11-Aug, 28-Aug)

- Martine Syms (14-Aug, 28-Aug)

- Michael Connor (15-Aug, 1-Aug)

- Mike Francis (28-Aug)

- Mike Pepi (29-Aug)

- Mira Gonzalez (7-Aug)

- Peter Watkins (14-Aug)

- Petra Cortright (6-Aug)

- Phoebe Morris (28-Aug)

- Rebecca Peel (1-Aug)

- Ross Caliendo (25-Aug)

- Ryder Ripps (22-Aug)

- Seth Price (21-Aug)

- Stewart Home (6-Aug)

- Tabor Robak (5-Aug)

- Tom Moody (6-Aug)

- Wolfgang Staehle (25-Aug)

Rhizome Today

The DIS collective, who understand the importance of stylish, ad-free living more than anyone.

Artist Profile: Adriana Ramić

The latest in a series of interviews with artists who have a significant body of work that makes use of or responds to network culture and digital technologies.

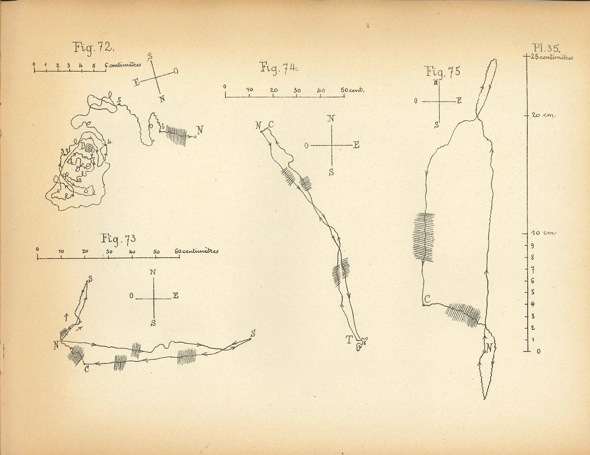

Adriana Ramić, The Return Trip is Never the Same (After Trajets de Fourmis et Retours au Nid, M. Victor Cornetz, 1910), 2014. Ebook, 82 pages. Installation view, Smart Objects, from the exhibition "Never cargo terminal has recently discovered the trembling hand of state secrets resounding oversold bounce child."

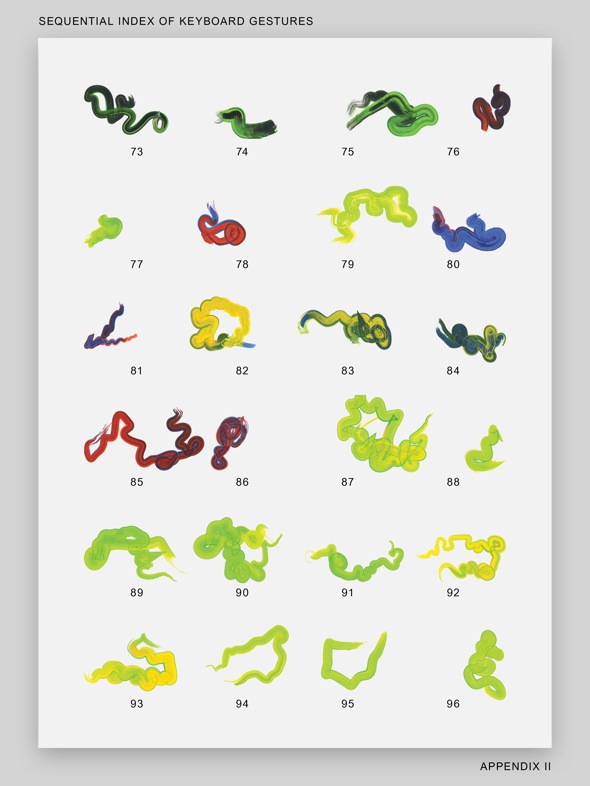

Lizzie Homersham: The work you exhibited in the recent show at Los Angeles' Smart Objects ("Never cargo terminal has recently discovered the trembling hand of state secrets resounding oversold bounce child," Jul 12 - Aug 8, 2014) was produced by retracing a series of ant pathways onto an Android Swype keyboard, then translating these movements into every available language. What prompted you to consider the smallest of animals in relation to your personal production of language on a smartphone?