Rhizome Today

Announcing Rhizome's Autumn/Winter Program

-

-

Rhizome Today

An index of topics and people discussed on Rhizome Today last month can be found here.

Rhizome Today

Rhizome Today

Rhizome Today

Stuart Marshall, Arcanum, 1976

Rhizome Today

Slide from Abdullah Al-Mutairi's lecture at CULTURUNNERS. In blue it says "I will participate" and in orange it says "I will boycott."

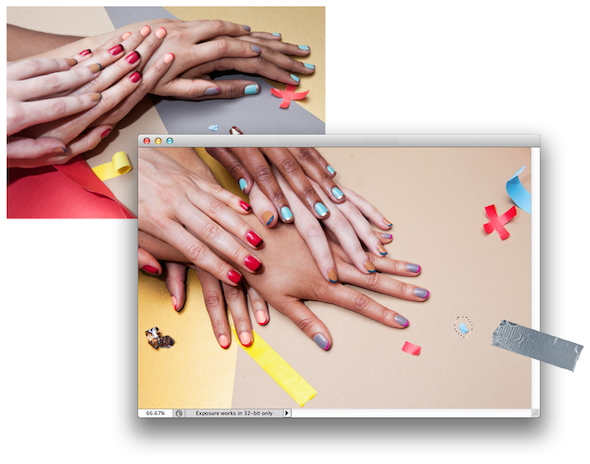

Nail Art: From lipstick traces to digital polish

From Charlie Engman's Tumblr.

For several weeks in August, news of an anti-date rape nail polish circulated on blogs and social media, igniting new debates with each posting. Created by four male university students, the nail polish was designed to be worn by would-be rape-victims; when dipped into a drink, it would indicate if it had been laced with one of three common date rape drugs by changing colors accordingly. Articles about this new prototype were irresistible to social media users—the way it tackled a trending, yet serious issue: the allure of staving off predators with fashion and the gimmick of seeing the colors change before your eyes.

Critics pointed out that the product reinforces the notion that it is the woman's responsibility to protect herself from sexual assault, serving as a reminder of the social acceptance of male aggression. A solutionist stopgap, it seems most likely to spur date rapists to change their lacing methods, while giving users a false sense of security.

One question that did not emerge during this discussion was the material form of this innovation, and its relationship to the body. As Lizzie Homersham and I wrote in a recent article for Rhizome, hands "problematize the boundary between organic human and inorganic tool." In the case of the date rape nail polish, the polished nail is deployed as a sensory device, a technological prosthesis that is also a part of our bodies.

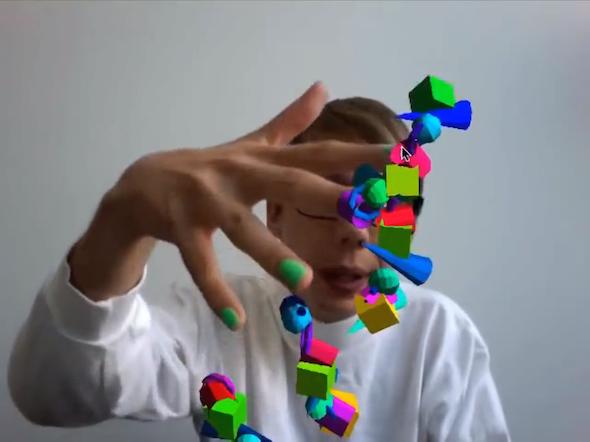

Jeremy Bailey, Colors of the Spectrum, 2010. Still frame from video.

Nails' position between "organic human and inorganic tool" suggests a possible way of thinking about the surge of interest in nail culture in recent years. Nail art is one of the fastest growing cosmetic industries, seeing an over forty percent increase in sales beginning in 2008.[1] In 2013, nail polish sales were set to exceed lipstick sales in the UK for the first time in history.[2] Nails are everywhere: Instagram and Tumblr accounts devoted entirely to testing out colors and DIY designs, mani-cams at celebrity award shows, and not to mention all of the innovation within the nail industry, such as gel manicures and decals that last for weeks.[3]

Nail art is particularly well-suited for online sharing because, compared to other cosmetic products, it comes the closest to embodying anonymity and universality. Hair products are made for specific hair types and makeup matches specific skin tones. Ethnicity, sex, and age are not as visible in nail culture: a nail is a nail and this allows images of the nail to circulate online in a particularly fluid manner. The nail is ready-made for social media.

This is not to say that there aren't more socially accepted styles in different circles, nor meant to diminish distinct cultures and communities that have emerged. But nails are content-driven. They are nearly standard units, blank canvases upon which one may use colors, styles, and patterns in expressive fashion. Nails' relative anonymity means that you can make your nails as outlandish and over-the-top as you want without the fear of becoming data points in a facial recognition database.

Jennifer Chan, Important Objects (2013).

Anonymous and object-like, and yet at the center of beauty culture, nails' ambivalent status, central to our look but peripheral to our appearance, contribute to a sense of fluid social identity that other cosmetics and accessories could never offer. In Jennifer Chan's Important Objects (2013), a film made for a selfie-themed exhibition co-organized and curated by the Museum of the Internet and ArtStack, Chan uses her nails to create a portrait of herself. The piece begins with an out of focus close-up of Chan's face, from about the nose down, telling us, "So, I was gonna make this video of my face in love, or in the throes of orgasm, but I'm now really out of love, so I thought I was just going to make something really beautiful." Repositioning herself further away from the camera lens, Chan stands at a distance with only her torso visible, placing her hands, one crossed over the other, in front of her body.

Throughout the video, Chan talks about how she loves everything too much. While she holds butter, bananas, an array of plastic, inflatable balls, and other textural objects, her nails change from a virulent green to periwinkle painted acrylic then to hollow, masked shells of negative space, revealing moving patterns in lieu of paint.[4] Rather than reading the emotions that we might imagine are on her face, like the expressions Chan mentioned, we instead know Chan through objects: those she selects, and her nails. If images of the face and body generally limit us, inscribing us in social hierarchies and taxonomies, our nails are much more open to transformation. This fluidity, in Chan's case, gives the video an emotionally charged intimacy that only evaporates at the end, when Chan's face appears on camera, saying "I don't care what you think of me." While her face is defiantly challenging, Chan uses her nails to show us a more personal and multifaceted portrait of herself.

Jeremy Bailey also explores a kind of self-portraiture through nail art with his Nail Art Museum (2014), but in a way that more specifically addresses the art system's political economy. While Bailey previously used his face and its visibility to "get famous" on the internet, he does not reveal his name or face to the viewers in this work. Instead, Bailey offers his hands, specifically, his nails,[5] adorned with nail plinths generated with augmented reality software written by Bailey. Bailey asserts that the artist's hand, foregrounded in this work, is "more powerful" than art institutions like the Whitney, the New Museum, or Tate.

More importantly, though, he also asserts "[t]he plinth is the most powerful object in a museum. It allows you to host any artwork." The plinth does the heavy lifting so the artwork can sit pretty while often going unnoticed. By claiming that this is the most powerful object in the museum, Bailey reassigns power to such supporting roles. On a physical level, nails play a similar supporting role; they can host any design: painted, adhered, sculpted, or even 3D printed.[6] Nail art is also the province of those who are relegated to supporting roles societally, as a feminine trope and a product of service economy labor, often, by the salon worker. Celebrating the power of the nail-as-plinth, Bailey aligns himself with those who play such supporting roles.

Former Estée Lauder CEO Leonard Lauder coined the term "Lipstick Index" during the 2001 recession when lipstick sales in America increased by 11%. Similarly, during the Great Depression, cosmetic sales increased by 25%.[7] Lauder and believers of the "Lipstick Index" would suggest that cosmetic sales increase during an economic downturn because lipstick is an affordable luxury, or what would be considered an "inferior good" in economics.

The same could be said of nail polish.[8] Nail polish sales have followed the trend of the Global Recession; beginning with the 2007-2008 financial crisis, nail polish sales steadily grew through the following years. However, the transition from a lip-centered cosmetic world to nail-centric one correlates with another economic transition: a service economy to an information economy. If lipstick is designed to smooth over the complexity of a face-to-face encounter between client and service provider, nail polish is an accoutrement for the hand that is documented and circulated on thousands of dedicated Tumblrs and Instagrams, simultaneously individualized, distinct, and deeply personal, yet dually disembodied and anonymous. These hands represent a certain kind of privilege, and they may even be prepared with the help of a salon worker, but they also are the hands of a new laboring class, and it is with them that Bailey throws in his lot.

Emilio Bianchic, Backward Nails (2014).

The daily nail art practice of Uruguay-based artist Emilio Bianchic, meanwhile, tends to destabilize such roles. Each day since 2013, Bianchic has painted his finger and toe nails in a hand-drawn fashion, creating popular designs like animal prints, flowers, jewels, as well as more unconventional creations including the Berlin Wall, fried eggs, Chichen Itza, cigarettes, cars, and menorahs.[9]

Participating in online forums, such as an exclusive nail art Facebook group for nail industry professionals in Latin America (which took months to gain access to), Bianchic posts photos of his designs as worn by him. One image of his feet with an animal print pattern garnered around 200 comments, most of them fixating on the hair on his toes, trying to discern if the digits belonged to a man or a woman. In the context of this group, Bianchic's gender identity becomes the primary topic addressed in comment threads, though his "ugly" designs still generate dismissive remarks. His nails—lauded by some members—are generally scrutinized for not conforming to preconceptions of who is allowed to participate in this community and what their nails should look like.

From Emilio Bianchic's Facebook.

In his Gender Conscious Free Nail Art Tutorial,[10] Bianchic asserts that "everyone has nails and everyone could be an artist." This statement, recalling Joseph Beuys, is not unlike the willfully naïve, "slightly ignorant and on character" idea promulgated by Bailey, that everyone is a famous new media artist by having access to digital technologies, despite many people not having access to these technologies.[11] In Bianchic's work, this is furthered by his embrace of the accessibility and affordability of nail polish. By inserting this routine into his daily life and artistic practice, Bianchic infuses the everyday with the possibility of fluid identities and bodily transformation and the political power of aesthetics, while also embracing what traditionally might be considered "outsider art." He then further queers this through his atypical nail-decorating practices, such as adhering acrylic nails backwards; gluing decoden objects, like crystals, on his toenails; and sticking small acrylic nails on top of his already painted nails.[12]

Emilio Bianchic, Gender Conscious Free Nail Art Tutorial (2014).

Interspersed throughout Bianchic's instructive comments in his DIY-inspired tutorial, phrases like "Destroy patriarchy" and "If anything doesn't look good you can always say it was consciously done" underscore the confrontational nature of this nail art practice. Bianchic's nails are an act of defiance, used to express the fluidity of these roles.

Because of the hand's dual status as body part and technological object, there is something that seems more than a little cyborgian about nail art. Relatively standardized and relatively anonymous, our nails seem tailor-made for social media sharing, which is one likely reason for the recent shift from a lipstick-dominated cosmetic culture to a nail art-centered one. Although understanding oneself as a cyborg has long been held up as a way of moving beyond restrictive social roles, nail art is cyborgian without being inherently liberatory. As the aforementioned anti-date rape product shows, blurring the human-technology boundary via nail polish may only reinforce gender roles. Even so, there is still something particularly powerful about such a small portion of the body having such disruptive potential, when artists like Chan, Bailey, and Bianchic draw on the possibilities presented by nail art and its circulation. Disembodied digits, both object and stand-in for an entire body, are fluid and mutable, like the identities, subject positions, and (shifting) forms of digital labor these artists inhabit and perform with the aid of prostheses and polish.

Notes

[1] "According to Euromonitor International, global sales of nail polish increased 43% between 2008 and 2011 – as sales of lip products grew just 7% and facial makeup 11%." Kira Cochran, "Nail art: power at your fingertips," The Guardian, September 25, 2012.

[2] Lisa Niven, "Nails or Lips?," Vogue UK, September 4, 2013, http://www.vogue.co.uk/beauty/2013/09/04/nails-or-lips---nail-polish-sales-exceed-lipstick-sales

[3] Some more bizarre instances of nail-obsessed culture include lemmings, My Strange Addiction: Drinks Nail Polish, long nailed celebrity LaRue's series of YouTube videos devoted to explaining how she performs daily activities, like typing and texting, with her long nails, and ASMR-like videos with women typing on keyboards wearing acrylic nails.

[4] Chan's ever-changing nails are reminiscent of the scene from Total Recall (1995), in which a secretary is giving herself a sci-fi version of a manicure, using an object similar to a stylus to instantaneously change her nails from blue to red with one tap. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aEyWavv1Lts

[5] This is not the first instance Bailey has made work about nails: ColorsoftheSpectrum.mov (2010).

[6] The Laser Girls, comprised of digital artists Sarah C. Awad and Dhemerae Ford, make and sell 3D printed nails. http://thelasergirls.tumblr.com/

[7]"Lip Service," The Economist, January 23, 2009, http://www.economist.com/node/12998233.

[8] "What Nail Polish Sales Tell Us About the Economy," Adam Davidson, December 14, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/18/magazine/adam-davidson-economic-indicators.html?_r=0

[9] Bianchic began painting his nails in 2012, often only using one color. About a year later, he began experimenting with more untraditional applications and fashions, which he then incorporated into his larger practice.

[10] The YouTube video is titled "EASY SIMPLE NAIL ART TUTORIAL FREE FEMINIST FIFA LANA DEL REY ROAR," to yield higher search results.

[11] Jeremy Bailey, conversation and email, February 17, 2014 and October 6, 2014, respectively.

[12] Nails are especially loaded cosmetic accessories in the LGBT community, with drag performer Alaska Thunderfuck 5000 proclaiming, "If you're not wearing nails, you're not doing drag." https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VsBdLc39X5w

https://www.facebook.com/AlaskaThunder/posts/10151584857991224

Rhizome Today

This is Rhizome Today for Thursday, October 9, 2014

Divorce, even between good natured, amiable, educated people, is apt to stir up a dust-cloud that covers and discolours all it touches. It is as if the sphere of intimacy, the unwatchful trust of shared life, is transformed into a malignant poison as soon as the relationship in which it flourished is broken off. If dragged into the open, it reveals the moment of weakness in it, and in divorce such outward exposure is inevitable. It seizes the inventory of trust. Things which were once signs of loving care, images of reconciliation, breaking loose as independent values, show their evil, cold, pernicious side. (p.31, Adorno, Minima Moralia)

- Yes. Knowledge is power!

- No. Why spoil the mystery?

The only question that counts is 'Are you someone I can trust?'

I can't be publicly eloquent about a subject that demands more careful thought. I can't choose a different topic so I'll mimic a problematic form.

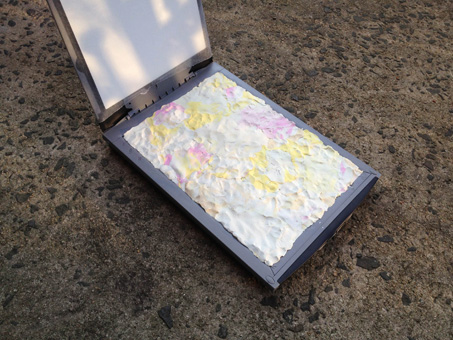

Unbound: The Politics of Scanning

There's a great scene in the first episode of House of Cards where the ambitious young journalist Zoe Barnes is sitting on the floor of her rented apartment's living room scanning the half-shredded documents of an education bill that was forwarded to her by her source/lover Frank Underwood, the Majority Whip. She's drinking wine, taking notes on her laptop, and scanning on her small all-in-one desktop printer/scanner. The next day she shows up at the office of the newspaper where she works with a 3000-word text and the 300-page document scanned, prompting her editors that "We should get this online right away."

Barnes's character is young and ambitious. Later in the season she moves on to work for a site called "Slugline," an early-Politico-like newswire, where "journalists post news directly from their phones." Her obsession with technology is used as a narrative device in the series to set her apart from her older, more conservative editors at the newspaper. And her ambition to upload information to the newspaper's site as soon as possible, to give the public the raw data before it can be filtered or analyzed, stands for her idealism.

The romanticized image of the scanner is based on the assumption that by scanning and uploading we make information available, and that that is somehow an invariably democratic act. Scanning has become synonymous with transparency and access. But does the document dump generate meaningful analysis, or make it seem insignificant? Does the internet enable widespread distribution, or does it more commonly facilitate centralized access? And does the scanner make things transparent, or does it transform them? The contemporary political imaginary links the scanner with democracy, and so we should explore further the political possibilities, values, and limitations associated with the process of scanning documents to be uploaded to the internet.

What are the political possibilities of making information available? A thing that is scanned was already downloaded, in a sense. It circulated on paper, as widely as newspapers or as little as classified documents. And interfering with its further circulation is a time-honored method of keeping a population in check. Documents are kept private; printing presses shut down. Scanning printed material for internet circulation has the potential to circumvent some of these issues. Scanning means turning the document into an image, one that is marked by glitches and bearing the traces of editorial choices on the part of the scanner. Although certain services remain centralized and vulnerable to political manipulation, such as the DNS addressing system, and government monitoring of online behavior is commonplace, there is still political possibility in the aggregate, geographically dispersed nature of the internet. If the same document is scanned, uploaded, and then shared across a number of different hosts, it becomes much more difficult to suppress. And it gains traction by circulation.

Collect and disperse

Grounds of the former estate of Viktor Yanukovych, Mezhyhirya. Via Flickr.

When Viktor Yanukovych—who was the President of Ukraine from 2010 and until he was ousted following violent mass demonstrations all over the country—fled to Russia in February 2014, hundreds of folders were spotted in the reservoir in the ex-President's estate. A group of journalists and activists arrived at the site and thus began the project to save and make available the papers documenting Yanukovych's corrupt, violent regime. They did not leave the mansion for days, drying and scanning the documents—a scenario that raises the bar considerably on Zoe Barnes. In an interview with Mashable, one of the members of the team (the technologist who built the website onto which they uploaded content), explained that their "first priority was to get the information out. The situation has turned out very well so far, but at the start we didn't have any idea whether everybody would be removed. So we wanted to get documents secured, and get them out in public to show that this is about transparency and accountability."

There are 23,456 documents on the group's website. Earlier this summer, they organized a public event in the ex-President's compound dedicated to the connection between investigative journalism, digital activism, and leaks. And they won the Reporters Without Borders Award at The Bobs, the best of online activism awards. Currently, the Ukrainian government is moving ahead with extensive anti-corruption legislation, designed to address public concerns raised in the aftermath of these disclosures. The importance of the Yanukovych leaks project is exactly in diving deep into that which was kept secret (journalists were never allowed within a safe distance of the President's estate) and making it available. And the enormous impact of this project is still being analyzed and reported. It is a pointed example of the tremendous democratizing effects that can be sparked by the act of scanning. The leaks group provide the first step in analyzing the time and impact of Yanukovych's rule by making the raw information available. But can that be called reportage? When we use terms like "democratizing," we should also bring up the question of responsibility, in this case meaning not only for making something available, but for generating analysis and public discourse around it.

We are living in an age where activism is marked by the information economy, where it is undeniable that Wikileaks is one of the organizations most influential in shaping the international political reality. And where making information available does, in fact, oftentimes mean making a difference. Because the release of documents is viewed as a positive, even heroic gesture, the analysis thereof may be lackluster. The visual image of the scanned documents provides the caché of accuracy and transparency, even in the absence of necessary mediation. Scans are raw material, not journalism. They offer support to a story and give the impression of truthfulness. Wikileaks, for example, benefits enormously from the expanse of the internet, allowing it to dump all of the information it makes available on its website, thus shifting the role of newspapers to no longer publish information, but rather, toorganizeit. As Julian Assange said, "It's too much; it's impossible to read it all, or get the full overview of all the revelations."

Scribd aesthetics

Partly as a result of examples like the Yanukovych document dump, scanned pages embedded in any news story have become an incredibly strong tool in reporting, a badge of transparency and credibility. By sharing a PDF, journalists are telling readers that their analysis is rooted in uncompromised information.

One of the visual tropes of the journalistic scan is the embed, in which a PDF is displayed in an iframe document embedded within other contexts. In most cases, this is made possible by Scribd's branded reader, which it offers to media partners ranging from the New York Times and the Chicago Tribune to the Huffington Post, TechCrunch, or MediaBistro. In a story analyzing a certain document, embedding said document within a Scribd reader—the advantage of which is that it's not downloadable and also that it allows readers to look at the content without needing to install a PDF reader on their browser—gives the story credibility. No one expects readers to go through the entire document attached to a story: that is why we read the analysis. But the image of reliability in reporting, especially post-Wikileaks, includes scanned documents, preferably with somewhat blurry text or at least with information crossed out in order to protect confidential information.

Scribd developed an HTML5 technology specifically to allow a way to share full documents planted in other stories, bringing it closer to what Wireddescribed in 2008 as "its goal of becoming the YouTube of online document sharing." And like YouTube, Scribd makes downloading seem unnecessary. But it isn't. When documents face possible censorship, for example, sharing them on Scribd makes it particularly easy to block access. The act of scanning is intended to create an easily duplicated file, one that can be copied into and shared from anyone's hard drive. But as with so many other online cultural forms, the scan is more often hosted with convenient, centralized, easily controlled services, limiting its potential for political disruption.

Search

While Scribd hosts scanned documents on centralized servers, other services centralize the indexes that are used to access PDFs. The sheer volume of scanned works now available means that their accessibility is often governed by algorithms, many of which involve Optical character recognition (OCR), the process of converting scanned images of text into searchable text. OCR has become extremely noticeable since Google includes text scanned via Google Books and analyzed through OCR in its search results.

The full-text search option in books is extremely useful in academia and is the central aspect of the HathiTrust Digital Library, a partnership of dozens of universities that allows users to search the texts of millions of books in its collection. The search hits only include the full citation (including page number) of books in which keywords are mentioned, and allows permitted users to access said books online. HathiTrust was taken to court for violating copyright law, which resulted in June in the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in New York State deciding that the full-text search offered by HathiTrust is "transformative," thus falling under fair use. From the court documents: "a transformative work is one that serves a new and different function from the original work and is not a substitute for it." The US court decision is fascinating in the way it considers how technology alters our use of text, because the content of HathiTrust is (theoretically) the same as the original text; merely transforming this text into data allowed it to serve a "new and different function."

The ruling that OCR technology is transformative paves the road for much circumvention of copyright laws on scanned documents. The push-pull between the contemporary digital media landscape and copyright laws tests the assumption that availability is a fundamental good and accessibility (via search) is a proprietary service. It remains to be seen how this ruling will be translated in a world of Google Books. (The Authors Guild, which is the institution that took HathiTrust to court, also filed a class-action lawsuit against Google Books, which was dismissed in 2013.) The case of Google Books and its unknown future (Google reserves the right to offer paid subscriptions to the content it scans, for example) is just one example of the fact that scanning information does not mean liberating it. In fact, oftentimes, it means some corporations stand to gain a lot from facilitating access to said information—and then charging an entry fee. When the printed page takes a digital, informational form, it does not mean that free access will inevitably follow. While many countries are in the planning stages of digitizing their cultural heritage, Google Books attempts to present itself as a shortcut, free for governments and potentially very expensive for the public.

The Politics of Circulation

Jenny Holzer, Top Secret 24 Black U.S. Government Document (2011). Sprüth Magers.

The loosening of control of information offered by a simple desktop scanner is changing our media landscape. In the information economy, making knowledge available can be a substantial source of political agency, and indeed, many of the most shattering political realizations on the international stage were the result of whistleblowers and larger organizations offering public access to knowledge that was intentionally withheld. The double representation—of technology and of political dissent—associated with the act of scanning in these contexts is emblematic of this moment in which we are still regulating the seemingly infinite amount of information that can be shared online. The apparent boundlessness of this technology equals the unimaginable amount of information out there, much of which is hidden from the public, much else behind paywalls.

As part of ongoing conversations about the effects of technology on political knowledge and participation, we should reassess the presentation of information and the way we read it. Just what the effect of digital activism on the world stage could be remains to be seen, but access to information definitely has the potential to reshuffle power structures. We just need to be very careful about the way we present it, lest we conflate access and a critical assessment.

Rhizome Today: Somebody Like You

Affective Communication in Me and You and Everyone We Know (2005)

Destruction Ceremonies as 21st Century Book Burning

Advertisement for destruction of pirated media in the Philippines.

Surely the irony wasn’t lost on Maulana Fazlullah when he took to his FM channel to tell his supporters to burn their radios. But Radio Mullah—as he fast became known—was just preaching on his shortwave what the incumbent Islamist government had set in motion on the streets of the frontier province. In 2006, the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA) government in Pakistan's provisional district of Khyber–Pakhtunkhwa had begun cracking down on ownership of electronics and recordings of all kinds. Muhammad Arif of the Center for Peace and Cultural Studies Peshawar remembers what happened when media products were suddenly found to be profane: "CDs, Video Cassettes and other gadgets were burnt on the directives of the provincial government. There were clear directives from the MMA government to remove 'obscene' material from the shops and the police had to prove their efficiency." Ordinary people—not only the most devout—and, in some cases, even the police, attended the ceremonies.

Having consisted primarily of local cassettes, videotapes, and VCDs, the MMA government's own bonfire of the vanities did not garner much media attention. Whether it's the looting of Egypt's Museum of Antiquities, the United States’ desecration of Mesopotamian sites in Iraq, the Taliban burning of the Afghanistan National Film Archive, or the torching of historic manuscripts in Timbuktu, the international community can generally be counted on to mourn the destruction of listed sites and priceless objects. But this is not the case when it comes to the destruction of contemporary digital or electronic cultural artefacts, which often receives the tacit approval of the international community as an essential part of the war against piracy. By shredding the "counterfeit" electronic media of their citizenry, governments of emerging markets signal their willingness to participate in a global economy and stage their official identity, while sacrificing the media archives of the future.

Steamrolling masses of CDs.

The sight of tanks and bulldozers crushing disks and tapes is now a familiar one in economies that struggle with—or are at least eager to demonstrate their disapproval of—the brazen alternate distribution networks of pirated media. For every obscure instance of religious zealotry, such as the MMA government's purifying fire, numerous nations are busy publicizing their deployment of military and industrial hardware in the ceremonial annihilation of the carriers of media culture. With a distinctly religious regularity, these destruction ceremonies become events of national significance, acting as a cohesive social and ideological force that initiates the willing into the symbolic body politic of the globalized world.

Through either their direct attendance or participation as subjects or electors of the state, citizens and media consumers are invited to make symbolic contact with broader political forces. More often than not, IP offices choose to stage their rituals on the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO)'s annual World Intellectual Property Day. In China, where as the saying goes "everything is fake but your mother," software and content management seminars in plush hotels are the soft sell to the wider battle fought via on-the-spot bonfires outside duplication factories. In Thailand, VIPs walk the streets after the ceremonial destruction and ask the curious to pay that little bit more for authenticity's sake. The Romanian Copyright Office has even begun shattering hard disks and memory sticks: the symbolic manifestations of online piracy.

If destruction ceremonies of pirated media products across the developing world are a response to global economic forces, they play an equally important role in producing and rehearsing specific national or local identities. At the turn of the century, Indian elephants were seen "stomping" out counterfeit cassettes. In Algeria, a destruction ceremony in October 2012 was adorned with anti-piracy banners that called to mind a street protest; attendees were invited to break pirated media over anvils with rubber mallets. The ceremony was trumpeted by officials as a stance in support of local artists and authors; they enlisted the public support of national celebrities Mohamed Tahar Fergani and Takfarinas. Despite this local emphasis, the ceremony came in the wake of pressure from the US and the WIPO for Algeria to crack down on copyright infringement.

Ceremonial sledgehammering of pirated media.

In press releases and news reports, these ceremonies are said to send a clear message about the government's commitment to facing the issue of copyright piracy head-on. But, like Radio Mullah's paradoxical edict, these public ceremonies of cultural destruction are mired in ambiguity, because governments often tacitly approve of media piracy while publicly condemning it. (For example, the Algerian government itself, as of 2009, was using approximately 50% pirated software). With their maritime namesakes, media pirates share a desire to subvert and profit from the constraints of a gush-up gospel legal system that allows creativity to suffer at the hands of competition, and this desire is not unknown to government officials as well.

Effectively cleaving new trade routes for major labels and production companies, the unilateral trade agreements intended to win the war on piracy instead serves as a means of controlling the economic progress of emerging economies. In 1994 the World Trade Organization (WTO) authored the TRIPS agreement, effectively ensuring that copyright compliance become a prerequisite for continued participation in global trade. The agreement laconically recommended that confiscated goods be "disposed of outside the channels of commerce." Much of the remainder of the document is equally ambiguous, with the aim of allowing countries to mete out punishments and deterrents as they see fit. The early years of the century saw the Office of the US Trade Representative (USTR) set the tone, threatening the nations of the world with inclusion on their annual Special 301 report "Watch List" and "Priority Watch List". From being branded as an outcast in the merchant caste to trade sanctions, the punishments can be severe. 2014's worst violators of international copyright law—Thailand, India, Algeria, Argentina, Chile, China, Indonesia, Pakistan, Russia and Venezuela—are under pressure to show their commitment to US trade norms. Like long-time offender the Philippines, whose name disappeared from the list this year, they are forced to capitalize on every haul of seized goods to provide evidence of their efforts.

Throughout history, societies have found certain kinds of knowledge to be so inexorably tied to their fate as to warrant designation as sacrosanct, making their unpermitted access an act of profanity. Not everything is allowed free circulation. State secrets, as the Snowden leaks have shown us, are guarded for a reason; their unauthorized release destabilizes existing power relations. The same goes for cultural bodies of knowledge, and as such, copyright can be seen as one of the primary mediators of social power. How these closely guarded objects or practices are protected tells us a lot about the structure of the society that clings to their efficacy.

Regional copyright offices, the WIPO, and the WTO would rather not think of their efforts as the destruction of knowledge, as book burning. Crushing, pulping, and shredding have more pleasant associations with recycling, with failure, and technological breakdown, and less to do with Nazism or religious fundamentalism. In the eyes of fascism and fundamentalism the content is profane by its very nature, but the sin of pirated media is far more ambiguous. If it isn't the content, it must be the distribution system, of which the carrier is considered a bastard offspring.

Cassette, CD, and VCD store. Photo: Majeed Babar

But what lies behind the "profane" circulation of cheap, mass-market pirate media is often a system of legitimate or "sacrosanct" distribution characterized by instability, narrow selection, and unfair pricing structures. In many cases, official media is prohibitively expensive, and pirated CDs and VCDs play to a market of lower-income individuals eager for the dissemination of their national culture, not its destruction. In nations with established archives, government holdings, protected collections, and frequent bequests, the distribution, dissemination, and ownership of cultural artifacts are taken for granted. Yet in emerging economies, many of which suffer archival crises triggered by turbulent recent histories, scarcity of funds or skills-drains, the spread of historic music, classic films, and golden-age singers is left to an alternative distribution system to fill the gaps. Thus, by designating pirated media distribution systems as "profane" and official media outlets as "sacred," national governments are destroying the vernacular media archives of the future.

This conflict between local culture and far-flung capitalists can be seen in the Philippines, where the lingering threat of Special 301 led to the foundation of the Optical Media Board (OMB), whose outlandish chairmen, youthful image, and bombastic destruction rituals helped secure the country's removal from the 2014 list after two decades of inclusion. The dubious accolade coincided with improved relations with the US, when in April 2014; the countries signed a ten-year defence pact. However, recent destruction ceremonies organized by the OMB pale in comparison to the one staged in Manila in early 2006. Mounted on an armored vehicle, then-chairman of the OMB Edu Manzano led the charge at the military headquarters Camp Aguinaldo. After the vehicle flattened over 100 million pesos' ($7.7 million in USD) worth of pirated discs, another batch was fed into a pair of giant shredders. As if it needed clarifying, Manzano confirmed to the mass of onlookers at the widely publicized event: "This is a war." But even before the arrival of cheaply duplicated media, a fear of media counterfeiters’ ancestor, marine pirates, had been indelibly woven into Filipino discourse. Before Spanish colonization, marine raiding was the traditional form of warfare, and one treated with the respect accorded to warriors. Upon first contact, the Europeans saw something different. Caught back home in the midst of a bitter battle to stop marine pirates clogging their trade routes, the colonizers saw the nascent Philippine islands as an archipelago of privateers.

Despite the successes of the Filipino assault on piracy, the unpopularity of Operation Dudula in South Africa demonstrates the contentious nature of the approach. Led by the poet and musician Mzwakhe Mbuli, this populist movement saw musicians themselves take to the markets and duplication factories to turn over tables and confiscate illegal merchandise. The operation soon generated toxic publicity through allegations of theft, looting, and racial assaults of migrant stallholders.

Consumers of the vast majority of media culture in Pakistan and the Philippines endure two prime examples of two different types of militant iconoclasm, with Radio Mullah on one hand and the OMB's armoured trucks on the other. Both countries also share an archival crisis, and suffered the devastating effects of military rule and martial law through the 1970s and 1980s. Until recently, the Philippines were thought to have been the last major nation without a national film archive when one was finally established in 2011. Now it is left to Pakistan to suffer that ignoble honor. For a country that so openly permits media piracy, it would be easy to blame this on the circulation of pirated films detracting from an archival impulse from forming. Yet the opposite is true: in countries such as Pakistan the sole reason for the continued existence and dissemination of films made roughly before the advent of VHS is the pirate media trade. With the majority of films now considered lost or damaged beyond repair, the archivists of a future Pakistani film archive would look to the VHS transfers struck from the original reels in the early 1980s as part of General Zia-al-Huq's stay-at-home cultural policy. These films, all readily available from pirate VCD shops, are in each incarnation potentially the earliest carrier form—or what might one day constitute an "original" master copy—and their destruction is the burning of tomorrow's archive.

In countries for whom access to legitimate media products is indicative of social class—pirate media encourages the lossy compression and transference of data to the most modern, economical carrier, the public destruction of which is a symbolic interruption in a long line of media migration. Destruction ceremonies in Pakistan and the Philippines, whose pirated media distribution networks kept alive an archival impulse in the face of government inertia, reflect two iconoclastic gestures to protect the sacred and punish the profane. The sacred lingers in every culture, expressed in those things that are denied open access, with the profane increasingly representative of the inverse effect of prestige pricing and luxury produce. In all cultural modalities there are dichotomies that set the transcendental against the everyday. Pirate destruction ceremonies are the lingering remnants of civilizations that have yet to fully grasp that culture is no longer only accessible to those with means, and their bonfires of the everyday will only continue to polarize a global community for whom technology and informational networks have collapsed the distance between the sacred and the profane.

Rhizome Today: CITIZENFOUR

Opportunity: Senior Developer (Part-time) at Rhizome

A day at the Rhizome office

Rhizome seeks a skilled, level-headed and friendly developer to maintain and develop the Rhizome website, databases, and servers. The Senior Developer will oversee all aspects of the site and work closely with the rest of the Rhizome team to develop technology-related projects. This is a part time, salaried position at 2 or 3 days a week, by negotiation. For more information, visit the full job posting.

Rhizome Today

Watch Now: Do You Follow? Art in Circulation 1

Streaming live from Selfridges Off-Site, Weds Oct 15, 1030am - 12noon.

"Internet circulation has made all art look the same."

"Why does so much new abstraction look the same?" asked critic Jerry Saltz in New York magazine earlier this year. Galleries, he lamented, have gone over to "copycat mediocrity and mechanical art," coming to resemble the generic look of shopping outlets rather than the "individual arks" of the past. In particular, Saltz criticized the influence wielded by "speculator-collectors," which many understood to refer to art world figures who use social media channels such as Instagram to generate attention for their favoured artists.

On this panel, art historian Alex Bacon challenges Saltz’ contention, suggesting instead that we are not looking carefully enough. Artists Martine Syms, Takeshi Shiomitsu, and Kari Altmann discuss the role that internet feeds play in their practice, arguing for different understandings of the problems and potential of "sameness" in art. Chaired by Rhizome Curator/Editor Michael Connor.

Rhizome Today

Rush Transcript — "Do You Follow?" Panel One

Work by Israel Lund at Eleven Rivington, June 2013

Do you follow? Art in Circulation

'Internet circulation has made all art look the same'

15 October, 2014

[Note: This is a rush transcript compiled by editorial fellow Anton Haugen. This document will be updated.]

Rosalie Doubal: This is the first in a talk series that we have been working on with Rhizome, "Do You Follow? Art in Circulation," and today, we are addressing the statement that "Internet circulation has made all art look the same." This is presented in partnership with Rhizome, and I am extremely grateful to Curator and Editor of Rhizome Michael Connor for his incredible work in producing this. Michael will be our chair throughout the series, guiding us through, and I will be shortly be handing it over to him. We are livestreaming today and we will be having a Q&A at the end. Thank you very much for joining us and thank you very much Michael.

Michael Connor: My name is Michael Connor, I am Editor and Curator of Rhizome, an arts organization based on the internet. It's a great pleasure to be back here in London, as a guest of the ICA. Rosalie has done amazing work in putting this all together, the whole team has made us feel very supported in what forms a major component of our Autumn program.

This panel is called "Do You Follow? Art in Circulation" and it kind of continues on from a panel we did with the ICA last year called "Post-Net Aesthetics." Before I turn things over and introduce our distinguished panelists who have joined us from places near and far, I thought maybe I would take a minute to situate where we are in that conversation and then bring up a couple of the themes that today's panel discusses. Each of the three panels has certain discussions that it's referencing. Today's talk is being livestreamed, which is I think why we are so brightly lit, so hello to viewers on the internet. I hope things are working well out there. All of us can use the hashtag "doyoufollow" to continue the discussion in social media, so I welcome you to do that in keeping with the theme of our panel.

As I mentioned, last year was the "Post-Net Aesthetics" panel that Rhizome and the ICA co-organized, which was curated by Karen Archey who did an excellent job with that. That panel was picking up on a conversation about the areas of practice of Post-Internet that had been widely discussed for several years up to that point. And I think you might be able to credit last year's panel with kicking off the post-internet backlash. Over the past year, we have seen a lot of angst build on that term, and we have also seen a lot of people criticizing it.

One of the things that has happened since last year's panel there has been an extraordinary number of different definitions of post-internet offered. Those definitions fall into three different kinds of groupings, all of which are valid because all language is made up, and so words can have different meanings. Thanks for teaching me that Zach.

The first definition is the market, stylistic definition that post-internet art is a kind of style that references the internet and is popular with collectors. The definition tries to trace it to aesthetic similarities or market trends in the art work. It's a kind of definition that has usefulness but it makes people feel depressed, generally. So that's one of the real reasons why this backlash has begun.

The second kind of grouping of definitions that emerged around post-internet would be the social and historical ones. Sort of between 2006 or 2008 and maybe 2013 or 2014, people were using the word "Post-Internet" at various places and times to describe different forms of practice or different communities of practice, and I think that definition is certainly valid. We have certainly seen people use the term in New York at different times with different levels of irony. There are different moments when it was picked up in London and reinvented and used in different ways. It also had different valences in Berlin as well. Los Angeles and San Francisco had their own kind of dialogue going. In all of these places, the term was applied in different ways and so there was a diversity of practices that were attached in this way.

The third way that people try to define Post-Internet is in the thematic way, where they try to find a certain philosophical basis that unites this extraordinary diversity of practice that has been attached to the word "Post-Internet." That is what most people instinctively begin with because one expects a term that seems so authoritative as "Post-Internet" to have some underlying philosophical kernel of an idea. That may not be the case, but there are arguments that have been made more or less successfully about that word and its thematic origins.

My own use of the word tends towards the social historical definition, but I do have some interest in the thematic definitions as well. For me, a lot of the arguments and discourse around Post-Internet that I have seen playing out have revolved around the phrase and ideas around "Digital Dualism." It comes from the sociologist Nathan Jurgenson who is actually a collaborator of mine on a series of Rhizome's "Internet Subjects." He defined "Digital Dualism" as a fallacy, believing that online and offline worlds are distinct, that we can think of an offline world or an online world or irl and url, that we can draw that distinction. The offline world is inherently structured by digital technologies, network connections. I think that is a true contention. At Rhizome, one of our core philosophical ideas is that the internet is not a sort of space at all but a process or a set of processes. Thinking of the internet in terms of a spatial metaphor at all is misleading.

Digital Dualism as a discourse is really connected to ideas central to Post-Internet. That there is online-work and then gallery-based work: the gallery, itself being an industrial model for circulating art work. Another way is in accelerationism, accelerating the contradictions of the system to an extreme position.

Returning to last year's panel, Ben Vickers' "Post-Internet is Dead (if you want it)," I think we can call that the beginning of the Post-Internet backlash, provided descriptions of a stance one might take in terms of a disavowal or refusal of the internet, to reclaim the idea that there is an offline space. On one hand we had this integration of online and offline space, while Ben Vickers wanted to reseperate the online and offline world. Also in that backlash space, we had the anti-internet art manifesto of Zach Blas and of course, Hito Steyerl's e-flux article "Too much world: Is the Internet Dead?" All of those were really interesting in manifesting different positions about the disavowal or working against the Internet. In addition to that, we had the Facebook study, where people learned for the first time, some how, that they were subjects of a large-scale social experiment, which is central to Social media. We also had the NSA-revelations, which were made possible by Laura Poitras' film-making and her ushering through of Snowden's leaks Glenn Greenwald, etc.

So a moment of extreme cynicism, and yet, I have not been this excited about internet culture since the dot com crash.

The panel came out of research we have been doing into, I suppose, well it started with our research on VVORK, because we have been trying to archive VVORK, which is a website which started in 2007; it was a very influential thing. All it was was a place where the contributors of VVORK would serially post artworks with just a title. They did use tags but they are not very visible unless you look very hard for them. They would never write anything, but you would start to see patterns emerging. They would post like five things about Michael Jackson when Michael Jackson passed away. There was this sort of implicit provacation that there was an inherent underlying similarity to what they post.

When it first began, a lot of artists responded negatively to the implication that a lot of art looks the same, that it was reducing artistic practice and that they were not giving the artist enough due. Making things seem very similar and depressing.

I think there was actually a kind of radical possibility in this presentation of similarity that VVORK gave us. To understand that, I think it's instructive to look at the next example, which came in between VVORK and Instagram as places where people would look at art on the web, which was Contemporary Art Daily. And here, we have longer post of multiple photos of a single exhibition with the press release. If the central contention of VVORK is that all art is this kind of collaborative process of authorship in which there's a lot of copying and ideas are transmitted back and forth and the individual artist as part of this embedded collaborative network of creative producers or of practitioners who are in some kind of dialogue, Contemporary Art Daily makes this kind of argument that the artist is somehow different and standing on their own and has something special to offer the world. That to me is more depressing than the VVORK perspective.

At Rhizome today, we are announcing back home in New York that we have come up with a new archiving tool, thanks to my amazing colleague Dragan Espenchied so [VVORK] is one of the first projects that we started to archive with this new tool. We consider the internet culture as process not space and in keeping with that, we archive pages as specific moments in time in which they are captured, and not as static pages which we download as files, so it's a different paradigm of digital conservation. That's what we're looking at here, VVORK on Rhizome.

But with this idea of VVORK and Contemporary Art Daily, I wanted to organize this panel to further explore this idea of sameness and difference, because in the past year it has been argued that all art is starting to look the same because of the internet. And we are to talk about whether or not that is the case. And if that is the case, if that presents an interesting set of conditions. So with that I am going to hand things off to Alex Bacon.

Alex Bacon: Thanks Michael. I am going to begin with perhaps the critically unpopular position, but obviously the one that inspired this particular panel which is "why does so much art look the same," but specifically in Jerry Saltz's case recently it was "Why Does So Much [New] Abstraction Look The Same?" He accompanied his article with these set of iPhone images that he took at an art fair. I think it's an especially kind of germane way of entering this topic in the context of Frieze week. Basically Saltz argued that the reason we are looking at this kind of work is not out of any kind of critical interest but rather the interest it has to a speculative, collector class.

I think that what's interesting is that it jibes with a perhaps more sophisticated argument by Michael Sanchez in Art Forum about a year ago ["2011: Art and Transmission"] that essential a lot of this abstraction was being almost produced for sites like Contemporary Art Daily, favoring of things like gray palettes and these kind of washed out images that would play well on the screen. But what I think that what's interesting is that [Sanchez's argument] presumes that there is this kind of power that collectors, dealers, and art advisors have over artistic production. It does not quit follow the timeline of a lot of the work in question because a lot of the artists who began working abstractly, the younger generation in the mid-2000s up to the present, started making work before this market boom. It's been difficult, to fully separate how much is related to the collector interest and how much is kind of in the aesthetic development, and whether or not that even matters.

Nonetheless, this certainly has then complicated further by creating this huge pool of artists. I often liken it to a kind of mall; everyone wants the Gucci t-shirt, but some people can only afford Old Navy, so there's kind of an artist for everyone. I think that's what I think Jerry Saltz lays out in his article, so I appreciate that.

I think an especially interesting focal point in this conversation has been what happened around Wade Guyton's inclusion in this Christie's auction recently. He was upset at the idea that his work was going to be auctioned, so he started posting on Instagram all of these photographs of him printing out this image, trying to emphasize the reproducible, anti-authorship of his work. Of course, this painting still sold for a record amount. I think it really showed that this collector class is more interested in having one of many paintings, rather than the original. I think what it also does is show us is [the collector's] relationship to the work; that they're being told almost by the work, what they want, so the seriality of the work has in turn produced this desire for multiples. Collectors, famously, are buying things in groups of ten, twenty, or more, but what I think that all this does is cloud the fact that the actual work, a lot of painting if we want to focus on that, of course, exists as an object in the world.

As a critic and as a historian (my background is in 60s and 70s minimalism, working with Ad Reinhardt and my dissertation is on Frank Stella), I can see certain of the similarities and differences. Looking at these things in person, some work stands out as an object. I really don’t want to install that difference between the online space (like an Instagram) through which this imagery circulates and then the paintings themselves, as if somehow they were inseparable because what I want to propose is that some of the most interesting artists working in this vein in fact embrace the circulation of imagery of their work, that they both produce work that stands as an object, but that they don’t go around saying “you don’t get it if you don’t see it.” You would say that, but at the same time, it has another life online.

One artist who has done this in a smart way is Israel Lund. For example, here you see his show at Eleven Rivington from last yearwhere he installed four canvases in the window of the gallery. When you walked by you saw them from behind, and when you entered the gallery, you saw them backlit, very much as a computer screen. He was playing off this idea of something he calls “analog .jpg”; this idea of this hybrid status for this work that is produced in this analog-mode via silk-screening process but that he doesn’t disagree with its evocation of a kind of screen space.

But I think what is interesting then is to compare it to history is that, of course, some people like to compare his work to Gerhard Richter. If we look at these two things on a screen, they do look very similar. Experientially in space, they are very different. Richter is building up dense layers of paint that he moves around with a squeegee, so there’s a very tactile, physical quality to the work. Even though someone like Lund is discussed in terms of process, in a certain sense, there’s more visible process in the Richter. In Lund’s work, you have an image that is very hard to place. It’s much more an image that could only exist in an internet age: an image where its very seductive and beautiful, but there’s no way to find a footing for your eye in the work.

Another artist who works in this vein is Jacob Kassay. His silver paintings, especially, offer a very interesting commentary on this notion of perception and vision, this way we are constantly finding our identity through uploading and downloading images. Constantly taking photographs and uploading them on to social media, seeing other people’s post, it’s a way that we understand our place in the world and what’s going on around us; it’s very much a mediator.

What’s interesting about Kassay’s silver paintings is that as you move around them they not only reflect and absorb the light and the imagery of the space around them, but they do this in a very fragmented way. As you move in closer to them, your image becomes more blurred, and as you move farther away, it becomes clearer. It creates this kind of interesting experience where your expectation of being fulfilled by accessing this work is always thwarted.

Fragmentation is really something at issue in Jacob’s work as a whole. If you see his more recent series of works, which are based off of the left-over remnants of paintings: both his own and those of other artists, which he began by stretching up exactly as they were found. This idea of the incomplete or the fragment is related to this stream of imagery.

All of this for me, seeing the work of artists like Kassay and Lund and thinking about older generations, for me, what makes it different, I think that for these artists painting is related to the history of painting in modernism, you can’t deny that. I think it’s equally related to the surge of technological devices in our lives: smartphones, tablets, HD televisions; all of which have, unwittingly, have a relationship to painting. Painting is, in a certain sense, accessible to audiences today where abstract painting was the most difficult work historically; maybe museums showed it, these people were very successful in that way, but they did not have the kind of commercial viability they did today. I think it’s in part because we are familiar with this kind of rectangle. It’s something that acts as a frame for our experience.

What then becomes interesting for certain artists like Lund and Kassay is that they use this idea that maybe the painting becomes a momentary stop in the circulation of images. It’s not that the images are either in or out of circulation but that for a moment, they are held so that you can consider them and really think about what they are doing. I think in our current moment that’s a radical and important gesture. I think also important because it leaves certain of these questions that you were suggesting Michael; it poses them and makes them open. You really think about, “where is this image?” Is this an image when I see myself in the Jacob Kassay painting? Am I thinking of Instagram filters? Is it a mirror? What is this relationship?

Of course, it’s to all of these things;I think this questioning is very important.

Michael: Great. Alright, moving over to Takeshi.

Takeshi: Hi

Michael: Takeshi has just returned from Georgia, the Republic of. He has been experiencing some sort of cold, which he is almost recovered from.

Takeshi: I'm ill. Sorry. So if I stop coughing and splattering.

My name is Takeshi Shiomitsu. I am an artist based in London. I’m going to talk a little bit about what I do in my work and then talk a little bit about howI consider sameness.

I make work that takes up both digital and material space, often presented in the same series.

Last month I showed this in London, made up of five paintings and one video that was played out of sync on two screens.

Earlier this year, I did a show with Sandra Vaka Olsen in Copenhagen with Arcadia Missa and 68 where I produced a series called Pale History made up of video, painting, and sculptures.

I take it as a given that the experience of using the internet to receive most of the written and image-based content I’ve seen on an almost daily basis has trained the way that I read and see. Similarly, I consider that my production methods and gestures are inevitably informed by my experiences and exposures to different digital and physical platforms and modes of production.

Through a repeated exposure to certain aesthetic forms or display mechanisms we are unconsciously taught what to aspire towards. For instance, the sterility of the screen-based image seems to champion an objective notion of utility, perfection, or distancing from dirt, resources, and labor, etc. etc.

I consider abstraction to have some play as an alternative to the pragmatism of symbols and signs. Using the non-specific or borderline specific as a way to advocate different, possibly more nuanced ways of perceiving. Along side that, I make these relatively hyperactive videos containing quite loaded imagery, trying to have a more heterogeneous conversation, if you’d like.

I don’t think it’s possible to advocate one way of seeing or doing over another. I am trying to open up the various different ways we could be seeing to cross-contamination, infiltration, or at least, present a mesh of conversation. I consider sameness or homogeneity as a perceived trait, as a product to the various filter bubbles we are all participating in and that we are given access to by our real world subject positions. I don’t think widespread image internet-circulation really exists, but it is perceived within hermetic subcultures that have high rates of image-turnover.

In processing a stream of images online, just like in any other structure, we are led to uncritically accept a number of neutral, underlying contexts for what we are seeing in order to comprehend it. This could be anything from a digital camera’s white point to Cartesian dualism. For me, this can be expressed in the way that as people who seem to understand or know culture, at some point, we had to learn and are still learning as it progresses the cultural, historical canon. Our experience of culture is always modulated by shared cultural frameworks. To say it another way, our interactions are rendered within the confines of the user interface or platform.

The backlash against the nonspecific or unbranded manifests because its lack of objective signifiers in a society where objectivity and pragmatism is ideologically dominant. What we accept as a neutral point in order to gain access has a lot to do with taste, which is heavily informed by our subject, gender, class positions and the influence of our subsequent communities. It’s harder to gain access if you’re not coming from a similar subject position; the content has very little context.

So most often our tastes, the things we are drawn to, are led by an already entrenched belief system that’s fostered by our subjective experiences. Capitalism tends towards segmenting these varieties of experience and privilege into demographic groups of which there are an ever-expanding number with the internet. Sameness seems to manifest as a hegemony of taste within a decentralized power-structure, fore-fronting the taste of those who can afford the time to generate content or don’t need to work, or simply have a lot of energy for production. So it seems that often in image circulation, youth culture or wealth culture gets proportionally more play.

In effect, the image streams of each individual is formed by their own social, cultural, class, or subject position, in a decentralized form of canon with a hyperactive but hermetic turnover. The hyperactivity tends to overshadow the hermetic through exposure.

Browser-based internet culture is an extension of the real world preoccupation with pragmatism and signs. The distilling of information dance of already-known truths and codes would suggest the moment of encounter should constitute the entire consumption.

That’s it. I just wrote some stuff down.

Michael: Thank you. We are going to have the general discussion at the end, but there are already so many things to talk about. I am going to hand it over to Kari.

Kari Altmann: Hi, I’m Kari, and my presentation is called "Similar Image Haul: Genre as meme, #SAME so I know it's real." Hopefully some of you will know what #SAME means.

What is it that makes you fave something? Sometimes it’s something that seems exotic, sometimes it’s something that seems super relatable and cheesy, and then there are those magic times when it is the perfect combination of both. Instagram is perfect for these kinds of images; actually most image-sharing social networks are king of this image right now. For all of the kind of creative tags that people use to respond and organize these images, the most important one is #SAME.

#SAME is also how images are now found for you: added to your feed, allowed to stay there, recommended daily. We can also decide what is the same through our own posting and tagging. The internet allows for a lot of tropes and sames to be revealed and also authored. You always have related content to your content. If you search my name, you get this image from a tumblr. A lot of works from my websites come up as related content.

I wanted to insert this tweet that Rob Horning made maybe today or yesterday. "The pleasure of algorithmic identity is in how we can seem to change how we are through such small, convenient gestures." I really feel like the small gestures are important just through tagging, reframing, recontextualizing. The same way that digital artists used photoshop to make collages or final cut to make film, you can now make sets of content that have the same effect.

I have used different social networks to upload my art, but in 2008, I started using tumblr to make my own image sets, my own decisions as to what was the same. Of course it was open to faving, reblogging tagging, and replicating by others, which happened very, very fast.

But it wasn’t just the content, the color, or the actual objects they are replicating, but they are also somehow replicating the reframing, the vibe, the concept behind what I was doing. They understand it, and they understand the language of it.

After this project and a few others like it, I was really addicted to this process because it started gathering peers at the same time that it was gathering content. For every person that jumped in, it would multiply the content even more. So I thought what if we could keep this all together somehow, track in someway and include that as part of the process.

I tried to create a more meta-site called R-u-ins which somehow catalogued all of these different projects and all of these memes and then tried, desperately, to keep track of every single person who would re-blog it in a way that seemed like they got or seemed like they knew what was going on, people who were adding and auto-completing.

It kind of blew my mind that just posting a sequence of imagery something else could be communicated, just by grouping things together, again these small gestures that affect the algorithm of how we read these things. As the project progressed, new memes would come out of just collective activity, things that no one really started, they were just tropes. Because it was online again, it could be read as tropes and similar content again, and regrouped again and put back into the same sort of process.

Not only have I started other group projects like this, but I have also started organizing my own website in this way and my own way of working

So for instance, this is an installation based around similarities, an ambiguation of similarities, and it also has similar, related content. It is a series that is constantly growing through tags, through possible collaboration, and it changes every time it is put in a show or put on a page.

This is also a project commissioned through the New Museum earlier this year. This is the start of a brand new meme about mobility; it’s a content set suggesting that all of these things have a similar backbone.

This is my current website, this bar on the right are links to those kinds of projects, the ones I’ve shown you and a couple more.

Michael: Great, thank you Kari. Ok we will finish with Martine, and then we will move on to general discussion.

Martine Syms: Hello my name is Martine Syms, and I’m based in Los Angeles. I’m an artist also, professionally, a designer. Interactive, not usability. But it's close enough, it doesn’t really matter

Michael: Un-usable designer

Martine: Yeah I design un-usable things. My primary concern is really with publishing in the broadest sense of that: meaning both to make things public and also to create publics around different information. I have a small press called Dominica or Do-min-i-ca, if you’re American, I guess. These are couple books that I’ve published. The last one was from David Hart whose a photographer based in Chicago. This one is from me called New Guards.

A lot of that work I’m interested in how audiences are seeing a set of information or a set of knowledge and creating the meaning through that and what the relationship is to putting that out and how people determine it. I tend to use popular forms. This image is called “Most Days Film Stills.” Earlier this year, on a label called Mixed Media Recordings, I released a 12” record that I describe as an “audio film.” It’s a table read. There are five actors that read this science fiction script, but then as a part of it, I created this film still that goes with that. The audio and the script are published separately, and there was a manifesto published by Rhizome actually that also was tied into that, called “The Mundane Afro-futurist Manifesto.” It continues to circulate; it’s in the latest issue of Third Rail Quarterly. I sort of like to have all these different fragments that add up to an entire project that pick up different audiences along the way and also add to what the meaning of what that project is through its circulation and distribution.

This was a project I did over the summer, this was part of it. It was an exhibition called “The Queen’s English”; it was also a reading room, which took as a point of departure a book called Black Lesbians, which was an annotated bibliography by JR Roberts that was published in 1981. I gathered all of the books from this bibliography, and I also made two other bodies of work: one, the text piece is from the dedication. There were these text pieces that were the author dedications, and then there were images that I created, original images, that looked like they were from the time period of the other books that were in the selection. I think a lot of this goes to reading, what Takeshi started to talk about. I’m also interested in my own reading. I think the feed, how it plays into me, I like to show what I’m reading, watching and looking at.

There’s a digital theorist Lisa Nakamura who talks about computers as machines for unseeing; I think that’s something I’m interested in. I think most of the art that I’m really drawn to is not really considered art at all. Maybe I like to try to see what’s unseen that’s why I go between image and text a lot. I wanted to play that Trayvon Martin video a bit.

This project, "readingtrayvonmartin.com," it gathered all of the texts, articles, links, and primary documents that I was reading, creating this personal bibliography, following the case after the shooting of Trayvon Martin. There’s a sort of person behind this text. In terms of similarity, I think the internet affects me by creating these contiguous sites of discontinuity. They are documents like testimonies, but they are also editorials. They show how the story moved through the media. But since they’re stripped of metadata and contextual information, they all turn into the same thing.

Michael: I kind of want to move back through the panel at this point. There’s a key issue which has emerged that needs to be addressed more holistically. Before I get into that, I wanted to ask. You mentioned distribution being an important concept of your work, but in 2012, you published a different article on Rhizome called “Black by Distribution.” You talk about how cultural objects can become “black” in process of how they are received in the world, that it’s not an inherent quality of the work, that it is acquired through the process of circulation or reception. In this panel, the idea of all art looking the same is also a question of an essential characteristic of the work and another way of approaching it would have been through discussions of authorship and reception. Is the idea of “Black by Distribution” at play in some of the works we looked at?

Martine: Yeah, it’s definitely something I’m still interested in. I’m interested in the relationship between those identity markers in sort of the more capitalist demographics that are being created. In 2011, I wrote a book looking at film distribution, taking the history of race-film, films made for specifically black ghettos within the United States, how those distribution patterns historically influenced recent films, stuff that would be marketed as a “black” movie today. They really have a very one to one relationship. It’s a distribution that was set up through discrimination effectively and because the market continued that way or even if you look at something like R&B—

Michael: Right, but in those examples, the power to decide what something is, is not with the audience or the artist but with the person that controls the channels of distribution. Is that true?

Martine: I think in some respects I would agree with that, but I’m also interested in situations and especially in my own work— me controlling the distribution of my work as a part of assigning meaning to it and creating audiences for it that will add to that meaning. So creating works like books and records, but also films, where I’m actively involved in how it gets out into the world.

Michael: The question that I wanted to get to is that we have two people who have been speaking to abstraction in particular and two who have speaking to figurative work. I think Takeshi, there was something you said, an assertion that the internet has this desire for a utility of symbols and signs. Is it true that the idea of things acquiring meaning through distribution, does that only apply to symbols and signs? Is abstraction exempt from that process?

Takeshi: No not at all. I mean, the sign of an abstract painting comes back to the artist themselves. You see an abstract painting and end up going “That’s a Gehrard Richter from 1980 something.” That ends up being the sign of the aesthetic.

I think my issue around this thing of signs is that it does not allow much else other than the things that can be faithfully displayed within that context within the terms of a sign and within the terms of an objective truth or understanding.

Michael: In the kind of play of meaning that happens on the internet, there are certain concepts that can filter through and can be taken up. Not concepts but signs.

Takeshi: It certainly serves a purpose, the internet. I think there are certain things that can’t be encoded into a digital way of communication.

Alex: Something that you said that was very interesting was this idea that maybe virality is contained within subcultures that have visibility. It seems to me that that symbolism with that Richter, we have that association, is certainly an example of a certain subculture that can recognize that.