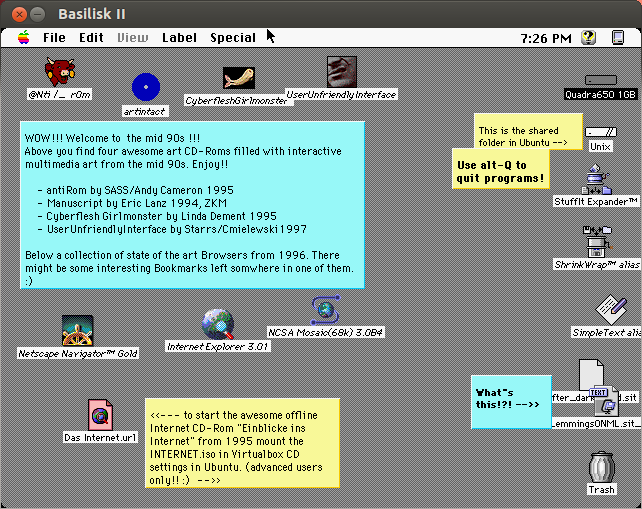

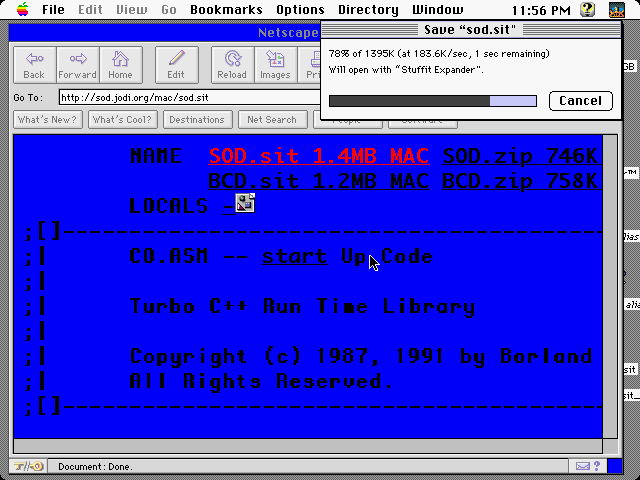

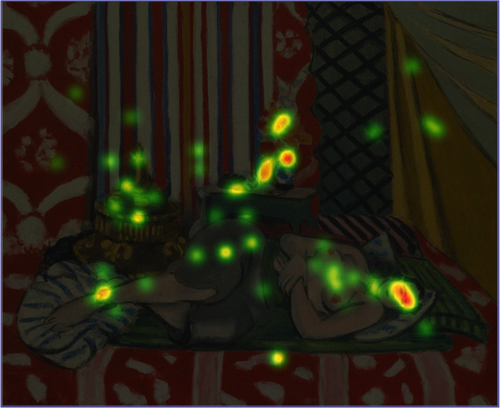

Your recent exhibition at JVA Project Space in London, Photographs and Slide Shows, primarily used LCD screens to both display and constitute work. These screens are quickly becoming the primary mode of public consumer advertising and there is something about the way the images of your sculptures rotate in their digital non-space that evokes traditional consumer store windows. What does the use of the visual language of advertising and public display communicate about the nature of your work or your identity as an artist?

I’m not really speaking critically about the language of advertising exclusively. I’m not sure it’s possible to do that without lapsing into a fairly dysfunctional rhetoric. I think within its traditional logic, this visual language functions in my work where it's drawn into conflict by other elements that it struggles to accommodate without having to be addressed. I intentionally want to polarise cliché characteristics, particular to advertising, within a process of trying to articulate other systems of representation in relation to them, such as that of a physical, three-dimensional form in a digital space. For me it’s very challenging to create and maintain a level of heterogeneity among different elements and control how they overlap and resist each other within the same work.

With the LCD screens you’re referring to I see their physical qualities as indistinct from any other quality the work presents as a whole in terms of their potential. I chose them partly because of their ubiquitous presence in the landscape. They have no branding, which in this case would interrupt their relationship to the images. They only display portrait, which interests me in their reference to other, more historical modes of display. They also have tempered glass faces that extend to the very edges of the whole unit so there’s no visible casing and no visible transitions on their surfaces. This adds a really severe flatness that I think interacts fully with the digital space the screens open onto and pronounces that (apparently) impenetrable surface explicitly. I think these qualities permeate the images being displayed and shift the way they're viewed.

I don’t want the mode or form my work takes to be consumed passively in the discussion around it. I feel a level of responsibility in determining why I should choose those screens and not, let’s say, an NEC Pro display panel, despite the fact the content can be arranged to work across both formats. I want to express this and be reflexive about it. I don’t think there is anything that escapes some kind of symbolic value. As ugly as it sounds, a canvas is full of meaning before anyone has made a painting on it and once they have, the painting doesn’t erase the canvas.

There is something quite magical and immersive about the landscapes you have pieced together in your two dimensional series, AAW (2012). The use of the traditional landscape format creates an aesthetic at odds with many people’s conceptions of digital or post-internet art. Do you feel that these works highlight the artificiality and construction of those environments or, rather, use technology as a tool to further the continuum of maybe a more traditional medium like landscape photography? Or both?

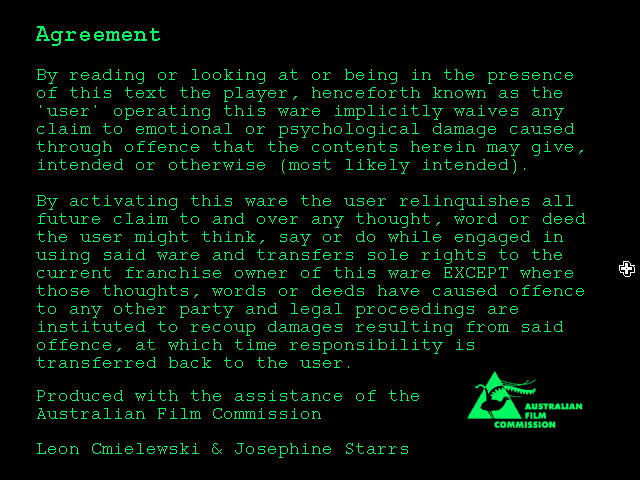

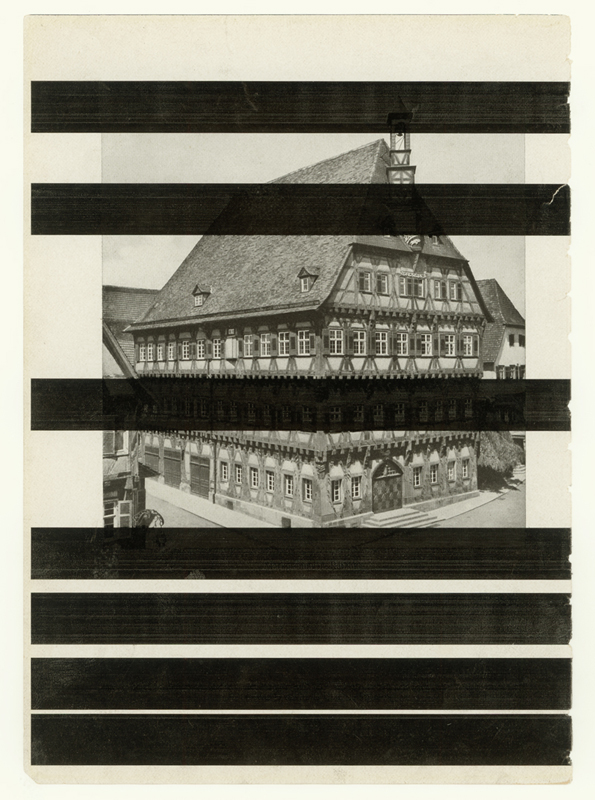

Before I source these images, they are already overloaded with signs belonging to landscape photography, art (in a more general way), pornography, the history of cinema, internet aesthetics and so many other recognisable forms and dialogues packed with clichés. The field I usually source the material from, I look to because of different ways it is now able to borrow from other images and build meaning into it’s own. I try to think about the way technology used in the process has been employed instrumentally to achieve this. These images are already the product of endless reproduction and their constituent parts intertwine evermore seamlessly. I don’t think it’s possible to determine which aspects of an image are ‘artificial’ in their construction anymore. I think the meaning this usually designates is stripped down and abstracted by new methodologies the digital environment gives rise to and accommodates.

I feel if images are being talked about in a way that’s relevant, the progression of traditional systems of representation should be focused on trying to evaluate and express how they are operating now in relation to technological realities that have transformed our encounter with them. Whether they appear as autonomous, physical objects or can be interfaced with onscreen. If the aim is to try and crystallise these things, I think the repurposing of digital technologies involved with images, in the broadest sense, is vital to art. One area of interest in this is that it allows me to work with images in a digital space and play with how they are produced in a way that feels very physical. I relate this to how I see the same technology mediating my environment in other ways. With the Autumn/Autumn/Winter series you’re talking about, the re-rendering process can be used to try and describe a set of relations technology has to images. I think it’s a perception of the digital space as tangible and real that helps create the sense of immersion you mention.

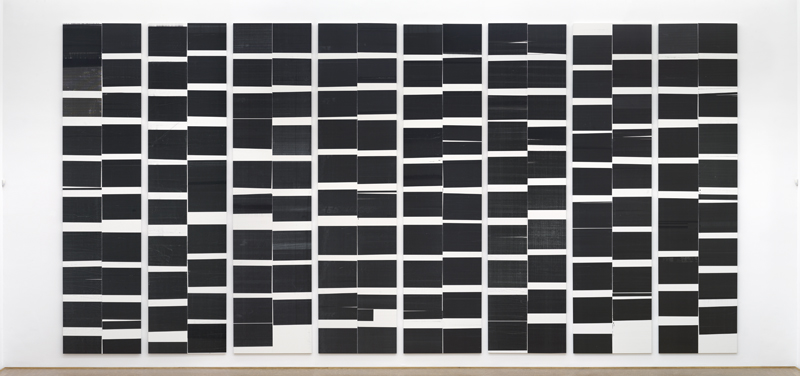

How do you work differently with appropriated images versus your own sculptures? What role does creating these intricate and incredibly time-consuming forms (see PBLOBZ, USB OPTIONII, 2012, Frame from Slideshow) have in your later processes of digital manipulation?

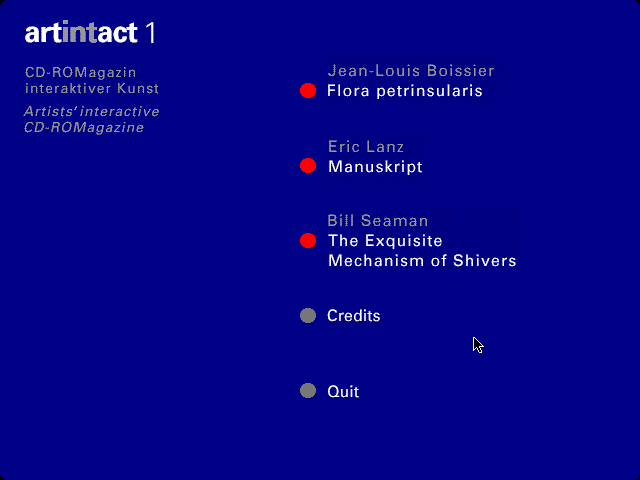

The background imagery of the content, which displayed on the screens at Jerwood for example, was a mixture of both reproduced imagery from works I’ve already made, such as video stills extracted from a mixture of my own footage and sourced material. These became part of a digital slideshow presenting as different surfaces, or options, against which the animated image of a sculpture was situated.

These screen-based works began with a very physical process; the production of a crafted, labour-intensive object that I made out of Plasticine with my hands. I enjoy trying to find ways of tricking myself into believing wholeheartedly the end result of this process will be a sculpture, which adversely gives it the potential to generate material and works within my process. I like the idea of squeezing everything out of it. The photographs I know I’ll take, I pretend will be used on my website to show the work in physical space, or as a reference when the object no longer exists or has left my studio*. It allows me to consider the resulting images as documentation in the traditional sense; the kind outmoded by digital technologies that have made it really transmutable. This is what interests me about Artie Vierkant’s series, Image Objects and also Parker Ito’s recent show in New York, The Agony and The Ecstasy. The situation gives me a lot to work with as the physical objects make their blurry transition into “digital non-space” as you put it earlier. The value people see in visible labour and craft is useful to me, as is the want for a tactile, tangible, three-dimensional form and spatial depth. It makes it worthwhile moving the object between a realm where these qualities belong, so naturally, to the physical, into a digital space that takes ownership of them and holds them up at a distance.

The possibility of an ongoing conjunction of media, processes and forms really interests me. An idea I’ve spent quite a long time with is Rancière’s notion of 'pensiveness', in images, as a potential to extend an action or a process and its ends in relation to the way we are able to evaluate and talk about aesthetic forms.

*bedroom

The curator of your upcoming exhibition (10/12/12-11/18/12) at The Green Room (London), Ché Zara Blomfield, and fellow artist Daif King, have both expressed an interest in the potential for digital art to say something relevant about contemporary society’s new forms of commodity fetishism. Does your process of turning flat images from glossy magazines into a “multi-dimensional landscape of space,” in your words, reflect an interest in the explosion of traditional systems of commodification?

Although I've said a LOT of stuff I don’t think I can claim ever having described those images as a “multi-dimensional landscape of space”. Although I think it is something someone wrote to sell my work ;D

Perhaps it’s important to try and start with the traditional idea of this fetishism, which attaches itself to commodities (in the Marxist sense) and use it in contrast. In the giant leap from this, to more contemporary ideas of what commodity fetishism can mean, different relations, in the way they are expressed as this fetishism, have become far more complex. Perhaps the internet could be sighted as an example nurturing these complexities because of the enormous set of data it makes accessible and reproducible. I think this means that where the relations Marx described between the human, social, political and religious etc. found their expression in the relations between more tangible ‘things’ (in the outmoded sense of the commodity), the objects of these relations are now far more abstract and illusive.

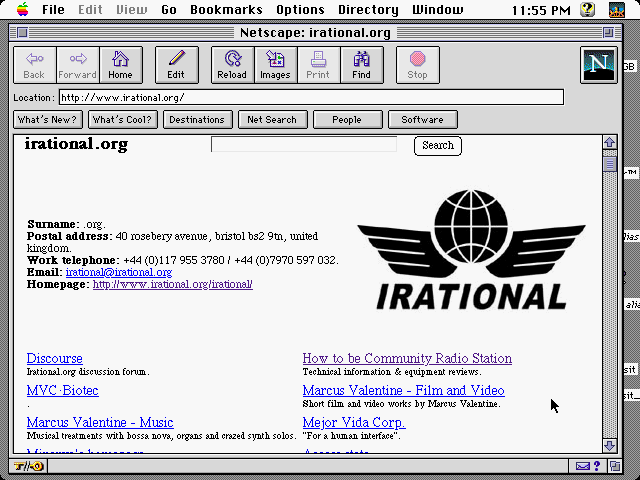

Although I think foremostly, we are still consumers of images, in a short space of time, I've seen the nature of these images changing radically. Where they proliferate in fairly familiar form on the internet, via LCD displays, as you mentioned right at the beginning, or via the array of gadgetry in our pockets, they also take on some really abstract dimensions. Beyond their depictions and our associations with them, I think images themselves seem very changeable, transmutable and personalisable across new formats. As a really straightforward example, I have an extensive archive of Nike ID’s, snapshots I’ve taken of fully customisable images that present as virtual walk-throughs, usually of a shoe. This is after hours spent on the Nike website and I can obviously share and collect them in innumerable ways online. I haven't bought any of the ID's I've designed. At one point I felt the biggest problem Nike faced as a brand, was that they made sportswear. It seems they’ve begun resolving this problem now. Pre-post-internet, I think co-branding exercises between products, individuals and other brands was perhaps a precursor and is still a relevant phenomenon. If I didn’t have access to a computer, perhaps I’d be more inclined to shave a Nike tick in my hair.

If digital art has the potential to speak about newer forms of commodity fetishism, then I think it has to be involved in a very reflexive relationship with technological means that give rise to them. In a simplistic way, the contemporary gallery space operates as a showroom; a place where you'd expect to find the tangible products of art that you can buy, that are also representative of a window onto an artists’ practice. If modes of display, for example, can be used to suggest that 'traditional' objects and images, through which fetishized relations are commonly expressed, are being transformed, or made inaccessible, within this space, as the space itself is supplanted by the digital/virtual environment, the discussion on newer forms of commodity fetishism can open up. If people don't see this in relation to my work (going back to traditional store windows) and the objects being depicted in the images simply create a passive desire for those objects, then I'm more than happy to oblige them a studio visit.

![]()

Age:

31

Location:

London

How long have you been working creatively with technology? How did you start?

I guess since I noticed and started to think more fully about the relationships this technology has to my environment, which naturally made it very relevant means to start making work with. In a really fluid way I became aware of this because the same technology presented the most immediate, available toolset to hand. I really struggled getting into a rhythm of working with the inconvenient clunkiness of producing objects that were both beyond my skillset and means.

Describe your experience with the tools you use. How did you start using them?

See above…and above : )

Where did you go to school? What did you study?

I’ve done about nine years of straight art education, which included multimedia and design. I finished the Art Practice MFA programme at Goldsmiths in 2010.

What traditional media do you use, if any? Do you think your work with traditional media relates to your work with technology?

Recently sculptures I’ve made, that are ‘reformatted’ for display onscreen, were produced using screwed up newspaper, Mod-Roc and Plasticine. I think these materials have a really domestic feel to them. I like the way Plasticine has a lot of personality and can be endlessly re-shaped and crafted. Sometimes when I think an older object I’ve made has reached the end of its life and I’ve got everything out of it that I can, I end up salvaging the Plasticine from it and using it in the production of other sculptures. I like the idea that even this very physical material, used to make something finished and seemingly static, lends itself to being re-shaped and reproduced into other forms.

If the tangible qualities, relating to the corporeal nature of a physical object, can be drawn into dialogue with the digital space in which they’re encountered, maybe this creates room to talk about the very odd overlaps, where attributes usually specific to each get very blurred. I would like this to start speaking about the way default categorisations, such as the digital and the physical, can be complicated and seen as inextricably bound up in each other to a point where these categorisations come into question.

Are you involved in other creative or social activities (i.e. music, writing, activism, community organizing)?

Creatively, I just don’t have time or energy to focus on anything else. For me the prospect of making any decent work means focusing all my effort on trying to develop my process. Although this also involves absorbing and trying to deal with as much material on and offline as I can. I have reading lists that I know are growing way too rapidly for me to ever have enough time, in one lifetime, to get through them!

What do you do for a living or what occupations have you held previously? Do you think this work relates to your art practice in a significant way?

I do some work at one of the bigger art institutions in London, within their development team. Although I couldn’t say this has any specific bearing on my practice as an artist, I have seen the inner operations of a big, public institution demystified. Ha ha, how sinister! I’ve had some fairly invaluable experiences as a result.

I’ve also done quite a bit of modelling work since my early twenties and I think this relates in some ways to my practice that are very obvious and in other, less obvious ways. The situation on set/location during a shoot makes it really easy to take up an extremely detached position in front of a camera and however many people involved. Then I feel fairly comfortable and relaxed. When friends try and take a picture of me if we’re out or something I feel far less comfortable. Despite this, I look at the images from a shoot and often feel I’m not looking at ‘myself’. I think it’s pretty vein as I know then, the reason I don’t like having a picture taken elsewhere is because I think it might capture a more ‘real’ version of me…in bad light, with my eyes half closed, while struggling to put some food in my mouth hahaha...I mean it can be a lot simpler, but the fundamental difference between the staged image and the one that captures something true, such as a facial expression you’ve never seen yourself pull, remains. Perhaps this truth, captured in an image, is harder to anticipate and far more shocking in it’s appearance than our expectations of all it’s cliché falsity. This translates in lots of other, perhaps more banal experiences that I can relate the sensation to.

Who are your key artistic influences?

Wow. Pass? Specific to art or not, although there are many, I think I only want to mention the ones whose work I’m looking at on a fairly regular basis and people around me who have been very generous in what they’ve given to my work. Ché Zara Blomfield (the director of The Green Room) woke me up to the emergence of a lot of artists who are spread pretty far and wide, although not online, where they form a cohesive community. She pointed out some really significant shifts that felt very dispersed, via the most hard-line approach to online research I think I’ve ever seen. I think it’s obvious when you look at her programme over the year long Green Room project. The eight artists involved are doing their first London solo shows and that list includes Petra Cortright, Daif King, Artie Vierkant, Jon Rafman, Rafaël Rozendaal, Kate Steciw and Anne de Vries. I’m also the only English artist involved. Make of that what you will. The community I think these artists operate within online has created a very relevant dialogue. It’s the first time I’ve felt linked to a community of artists, via shared concerns, that has informed my practice in a really productive way, although I still feel very new to this in relation to how it’s begun influencing me.

In a more general way I think filmmakers and writers have had a far greater impact on my practice than artists. Despite this, I’m very aware that I want my work to be engaged with other work that’s producing a dialogue I think is relevant. Usually this has a lot to do with it’s relationship to non-art related fields that I’m interested in and would like my work to talk about. I really enjoy seeing how other artist's are talking about concerns I share. I think it's a good way of gaining perspective on the moment.

Have you collaborated with anyone in the art community on a project? With whom, and on what?

Not really beyond the experience I mentioned above and obviously this is neither art community or collaboration in the usual sense.

I collaborated with Dan Shaw-Town for about three years, throughout my degree, rather than on a project. We made all of our work together and didn't have independent practices at the time. We were actually interviewed together for the MFA at Goldsmiths, on the basis if we were accepted then it would be as a collaboration. We were bombarded with way too much information to continue working together when we started there, although we still had a really productive conversation going and an understanding of each other that I haven't experienced with anyone else.

I also collaborated with four artists on a public sculpture commission for Terminal 5 at Heathrow airport a few years ago. Peter Joslyn, Magali Reus, Tim Bennett and Dan Shaw-Town. There were a lot of meetings in boardrooms and the process felt something akin to The Apprentice, in that it doesn't really matter what you're selling, as long as you can sell it. I remember one meeting with a military expert who gave advice on having the material we intended to use treated so that, in the event of a bomb blast, the sculpture wouldn’t shatter and create secondary projectiles that might kill people. He told us the most common cause of death in such a blast is usually due to these secondary projectiles, namely glass, flying across the terminal as a result. When someone is talking about these things in relation to a sculpture you’re going to make… I guess it made me feel a very long way from my studio, but I also learned how to work with a relatively large budget : )

Do you actively study art history?

I think having an informed approach to making art necessitates studying art history to some extent. Where there are gaps, it can sometimes be profoundly obvious in work that should have them covered in relation to its context. This has never struck me as a good thing.

Do you read art criticism, philosophy, or critical theory? If so, which authors inspire you?

Yes, it’s something I enjoy a lot even though, often, it involves spending a few years with a text and just going back over it and over it, especially where philosophy’s concerned. I love the way it’s meaning and relevancy changes over time. Where I’ve found philosophy and critical theory really challenging and useful I’ve enjoyed trying to unpack it and get to grips with it. Once I feel I’ve managed I think the reward is seeing complex ideas translate into even the most simple aspects of my life. Writers that I often come back to are Bataille, Benjamin, Baudrillard, Deleuze, Rancière…I think The Emancipated Spectator is a truly amazing book. The list goes on but I guess these are just the ones I’ve liked over a very long period. I’m also reading, while writing this, Parker Ito’s recent DIS magazine interview and Claire Bishop’s recent Artforum piece, Digital Divide (which I’m finding…difficult). Earlier today I read a long conversation with Katja Novitskova on cmdplus via Twitter. I mean it’s endless, but I love how I can dip into this information when I feel I want or need to change my perspective.

Are there any issues around the production of, or the display/exhibition of new media art that you are concerned about?

All that I’ve encountered, in the sense I enjoy thinking about them. In relation to my own practice I don’t want anything to escape consideration but I think that’s specific to my work in the way I want it to manifest physically.

Around the exhibition of ‘new media art’, it can be very challenging to lots of well-established conventions related to display and the space in which these challenges can be met. I think it’s amazing watching new forms and modes of work occupying different spaces, both virtual and physical. I’m excited by the way this often dovetails neatly with the technology I’m familiar with and seems to be moving at a pace that’s current. I feel as though a lot of the work I’m interested in is making demands of itself that its history is too young to answer. In this sense I think it’s genuinely experimental in the concerns of its production, display and exhibition and that’s a really exciting prospect.