Untitled, 2012 archival inkjet print.

Many of your works seem interested in the tension between analog and digital in the creation and reception of a work, like physical xerox scans of the screen of an iPad. To what degree do you connect a piece to the technological platform on which it was made?

The Pad Scans are scans of an iPad. The iPad is confused by the light from the scanner that produces heat making it think it’s being touched. So the scans are capturing the iPad rolling over to another web page, making visible these digital or web in between spaces.

Error feels a sign of humanness. For me it’s important to insert that into an image or work dealing with mediation and technology. In this constant looping between the physical and digital worlds images are unstable in that they are left always open to reuse.

I also recently learned the term ‘retronym’, which feels a linguistic insight into my working process. (A paralleling of technological advances and in the face of them a return to the past to update/qualify/recontextualize.)

Your naming conventions vacillate between identifying their originating platform (iPhone Videos, Pad Scans) and describing their final form (Prints of Plays). In terms of these degrees of mediation from an initial image, how important to you is the ultimate format of the work versus its role in destabilizing that image’s objecthood?

Everything is important in different degrees at different times in different works in different ways. There is so much process, yet when pieces are ‘finished’ as in hanging on a gallery wall there is no separation between image and form or object and picture. Though this unification is so fleeting, as it lasts for the course of a show and only if you are standing in front of it. The reality is that’s not how the majority of viewers experience a work. So instantly there is another mediation through online jpegs of the show as install shots or as specific individual works. So then the reality becomes that maybe there is no ultimate format. No singular state of importance heirarchy.

A recent show at Foxy Production (NY) wrote that through the physical manipulation of photographic prints [by tearing, cutting and folding], “any trace of the original context evaporates.” Critic Sharon Mizata suggested, however, that similar works of yours retained traces of portraiture. Would you place these works in the tradition of artists like Lucas Samaras who have used new media to consider or distort personal identity?

Neither of these statements are totally accurate. Though much becomes abstracted over the course of generations of shooting and reshooting, there is a vital tension between the recognizable and the unrecognizable, the obvious repeated shape of a pixel, a mouse’s arrow, a staple or paper tear. I was curious to read the comment of works retaining traces of portraiture as I never shoot people directly, though there are endless traces of fingerprints, marks, dents as remnants of presence.

You have shown many times over the years with your husband, artist Brendan Fowler, most recently in the current exhibition at The Finley (LA). How does the selection process work for these indirect collaborations? Particularly in the show at The Finley, part of a series on artist couples, how did you approach using objects to communicate something about the relationship between romantic love and creative partnership?

This is the second time Brendan and I have shown together (ironically both have been in domestic settings). I made a Pad Scan of an image of the Finley space, the staircase and a view from the inside which you couldn’t see from the outside. Because many viewers experience the show from the outside I wanted to embed the work with a vantage point different than what was afforded. The piece brought the architecture into the fold, while Brendan’s added to it by installing a wall at the top of the stairway. This is part of a new series of his where walls double as art object and functional support for another artist’s work. A literal reason our objects were in partnership is because my work hangs on a wall and he made one.

Stephen Prina and Wade Guyton committed to a 10 year collaboration where Prina would make a Push Comes to Love piece on top of one of Guyton’s Untitled inkjet paintings. What’s interesting is that they remained 2 individual pieces with their own autonomy and title, on top of one another.

I wouldn’t have thought I was interested in a collaboration under the premise of a ‘couples’ theme, but Sarah and Jeff’s rigor and thoughtfulness in mounting shows whose premise would not necessarily be given space within a traditional art institution is an incredible thing I feel lucky to have been a part of.

You wrote a text to accompany an exhibition at West Street Gallery where you describe the haptic process of scanning – running your fingers over the papers and the plexi and end with the amazingly simple line: “my scanner never gets cleaned.” Is there something about the indexical nature of technology that interests you – like Freud’s mystic writing pad? Would you describe your work as an attempt to reveal or conceal those fingerprints?

Freud’s mystic writing pad is a beautiful analogy, as there are endless (at times imperceptible) traces of past workings, use, and action on my prints and in my images. How information moves, morphs, is abridged, footnoted, reworked, gains artifacts, is lost, is rediscovered all frustrates and inspires me.

Age:

32

Location:

Los Angeles

How long have you been working creatively with technology? How did you start?

My mom was a painter and so from a young age we were constantly doing art projects, though I never really loved art class in school as I was a shit drawer and just didn’t enjoy it. The most incredible thing happened in 11th grade though when a media artist started teaching photoshop and video classes (this was maybe ‘97?). My mind was blown and I spent hours and hours shooting and editing. Making art really came alive for me. I then went to college thinking I wanted to major in video though after my first year I transitioned into photography, I kind of went backwards, finding the still image from the moving.

Describe your experience with the tools you use. How did you start using them?

Well, I got the internet in 7th or 8th grade in the form of America Online. I would sneak downstairs and stay up for hours and hours every night in chat rooms, talking about books or my parents or just escaping into some heavy RhyDin. I was young enough that the internet formed me, but old enough that I have the imprint of a time before it.

Where did you go to school? What did you study?

I went to Hampshire College, an amazing weird magical place where you design your own course of study, without the traditional structure of majors or grades. I studied feminist theory, cultural studies, art history, art practice.

I also began getting my masters at Royal College of Art in London but hated grad school/art school and left after two terms. One incredible thing I did experience was John Stezaker as a lecturer whose insight and poetry has stayed with me.

What traditional media do you use, if any? Do you think your work with traditional media relates to your work with technology?

At this point, using a digital camera or a scanner or printer IS traditional media. These distinctions, for me, don’t really exist anymore, and I question how useful they are for us all. I lost my mind over a totally conservative and out of touch article in the recent Artforum by Claire Bishop called ‘The Digital Divide’ whose premise was based on continuing these distinctions (as well as just not paying attention to anything artists are doing these days. And not in some back alley niche, I mean Wade Guyton has a show at the Whitney!!!)

Are you involved in other creative or social activities (i.e. music, writing, activism, community organizing)?

Since moving to Los Angeles I’ve begun giving feedback on scripts and movies. It’s such a funny part time LA gig. I also just finished helping to produce a short called Sequin Raze written and directed by Sarah Shapiro.

I feel energized by the potential of inserting ideas directly into a larger popular dialogue. The number of eyeballs that watch TV and movies, the way that whenever I visit my family this is the one thing we can all talk about and the steadily rising bar in television quality I find inspiring.

What do you do for a living or what occupations have you held previously? Do you think this work relates to your art practice in a significant way?

When I lived in New York I shot more straight photographs. I couldn’t afford a studio so this was my way of working, it felt contrary to my mixed media approach but it was what it was when it was. I also at the time was focusing on starting a business to make a living and not rely on art. In 2006 I started a personal styling business with a partner which I still do for a main chunk of my income. Thankfully this affords a flexible schedule and time in the studio as well as a way to pay my rent totally separate. It’s a kind of creative problem solving. I also appreciate the human interaction as studio time is wonderfully and painfully solitary.

Who are your key artistic influences?

Cady Noland, Steven Parrino, Louise Lawler, Wolfgang Tillmans and Wade Guyton. Also, Anne Collier, Josh Smith’s fucking punk way of storming through the art world, Oscar Tuazon and K8 Hardy.

Other things happening right now I’m really excited about: the band Hoax, Andra Ursuta, Asher Penn’s Sex magazine, Lil B’s endless output and end of meaning, a new era in television programming! Molly Soda, Oliver Laric, Frank Ocean’s storytelling, my trip to Documenta 13, street wear (Hypebeast, Supreme, Nike Frees), Heather Guertin stand up...

Have you collaborated with anyone in the art community on a project? With whom, and on what?

Not direct collaboration, but some of my most value dialogues as of late have been with a friend and great artist Artie Vierkant.

Do you actively study art history?

Sporadically, though I don’t know if you can count searching out works or artists through google ‘study’ in the way I assume you mean.

Do you read art criticism, philosophy, or critical theory? If so, which authors inspire you?

I read artforum, frieze, mousse, kaliedescope, May and other art magazines regularly. Also the NYtimes reviews...But I have a horrible memory so always forget everything.

Judith Butler rocked me in school and Illuminating Video was formative when my focus was video. I recently loved reading the 18 pg press release for Merlin Carpenter’s ‘Tate Cafe’ show at Reena Spaulings. It was a talk/taking to task between him, John Kelsey and Emily Sundblad which was totally fascinating. I don’t think its on the website anymore but if anyone wants it I c&pd so will send to you.

Are there any issues around the production of, or the display/exhibition of new media art that you are concerned about?

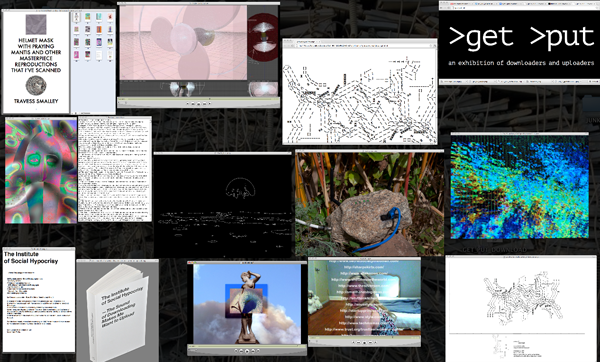

Again I feel like this distinction in my mind/work doesn’t exist. So what I think about is the display of art. I’m fascinated by the reality that most people see jpegs of the show online, and want to bring that into the fold of a work, build it into a piece so there is a sort of doubling down when you then see an image online. So collapsing work and installation document, creating ruptures or confusion in the process of online viewing is part of my concern with display.

Also just the consistent challenge to make and display work that feels activated, energized not totally tamed within an art system, numbed or neutered in the context of a gallery.