Map of East End Net, London. Via.

Let us summarize the principal characteristics of a rhizome: unlike trees or their roots, the rhizome connects any point to any other point [...] It is composed not of units but of dimensions, or rather directions in motion. It has neither beginning nor end, but always a middle (milieu) from which it grows and which it overspills.

- Deleuze & Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus

Thus is described the rhizome, the symbol of the internet age. When Michel Foucault said that the 20th century may one day be called Deleuzian, it is doubtful that this is what he intended. And yet, the language of this young, networked century so far is mimicking the speech of the philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari.

The language of Deleuze and Guattari is employed by everyone from the Israeli Defense Forces to this arts website, including any number of for-profit and non-profit startups in between those poles. War machines, companies, NGOs, and arts organizations all find utility in a philosophy that describes systems moving according to programmatic algorithms, breaking through what was solid, and re-writing the codes of meaning. War, commodities, society, and art all function according to their own programming. The public is coming to terms with the knowledge that the internal coding of networks is what defines future possibilities in the 21st century.

And yet, we are often too quick to tell ourselves that this programming can be rewritten for the greater social good. In our enthusiasm for the rhizomatic fruits of this new century, we often neglect the technology itself, replacing it with our ideas of what the technology could be. It is far easier to wield ideologically expedient speculative fictions than to develop socially expedient tools.

Consider what might be the most rhizomatic technology of them all: the mesh network. In words it is the perfect rhizome. Independent nodes set up the same piece of software in their network router. Every router connects to every other router, forming a multi-dimensional web with no central point to be disabled. It is "legion," to use a familiar term from contemporary parlance: each point is not a separate unit, but n-dimensions of distributed power. Some routers are designed to connect to each other ad hoc, over the air, without needing any wires between them. Even cell phones can connect in such a mesh, promoting a vision of infinite, pocket-sized nodes, deployed at a protest or as a hedge against infrastructure-destroying natural disaster. They could be manufactured in bulk, as cheap as a Raspberry Pi, solar-powered, disguised as innocuous light fixtures or other small appliances. The mesh network vision is of a rhizomatic network that is local, horizontal, self-healing, non-hierarchical, and scalable. Philosophically, its kung fu is perfect—bending like a reed in the wind against any foe, whether deployed by Occupy, by Egyptian revolutionaries, against censorship, war, flooding, poverty, or ISPs. In language, it is everything we expect from the future, the fantasy of certain post-structural technological desires.

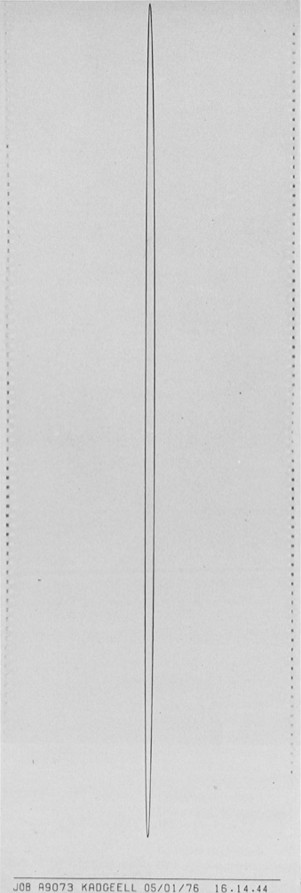

The rhizomatic computer network, as an idea, is almost as old as Deleuze and Guattari's oft-cited tomes. The original ARPANET network topology was meant to route packets around network outages, but had fixed addresses and routing procedures. Usenet, on the other hand, launched in 1979, allowed any number of independent host servers to connect to each other and route messages through the system to the end users. It didn't matter where and when those servers connected, the message would eventually reach recipients as it propagated throughout the system.

ARPANET diagram, 1969.

Cellular phones were also a precursor to the idea of mesh networks. The cellular concept was first proposed by Douglas H. Ring and W. Rae Young in 1947, and deployed by the Japanese NNT cell network in 1979. Unlike other radio telephones, the cell network passes a particular handset's call between a number of towers as it moves through these local "cells." Rather than have a central tower antenna that must broadcast across an entire city to every device, multiple small towers share the load between them to cover a wider area and preserve radio wave bandwidth.

Usenet still made a distinction between servers and users, and cell networks route communications between handsets only through towers and their centralized backbones. These not-quite-analogous scenarios hint at the truth of mesh networks: they are not as much of a mesh as they are described to be. Centralization is as much a natural feature of technological systems as rhizomes. A fully-connected, large-scale mesh network is extremely impractical. If each node actually has n-1 connections—a connection to every other point in the node—that means that a mesh network must have n! connections total. As the network grows, the number of necessary connections grows exponentially.

Most mesh networks are, therefore, only partially mesh networks. There are backbone nodes, with stronger transmission capabilities, handling most of the traffic through a possibly asymmetric, and yet relatively centralized structure. A business with fiber optic lines installed can handle much more traffic than your WiFi router at home, and so the network favors those nodes for efficiency. A mesh network is not a mesh, but various groupings of stars, trees, hubs, and other shapes of network topology.

Semi-connected mesh networks still have weak points, bottlenecks, and vulnerabilities. These vulnerabilities can be designed out of the system, to emphasize quick routing and redundancy while not creating superfluous connections. But then the network is not as ad hoc and fluid. It is less like a rhizome, and more like a forest of trees.

If the mesh network software or hardware isn't working, as sometimes happens, then a mesh topology is beside the point. The One Laptop Per Child program, which designed a laptop costing less than $100 to be used in developing countries, was built with ad hoc WiFi meshing support so that internet connections could be shared between computers. However, in practice the feature was buggy and hardly used.

The mesh network is also limited by its own edges. TOR software encrypts web traffic and bounces it around internal layers of a worldwide mesh network, allowing users to connect to the internet without their content being tracked. However, it can only encrypt material inside its network, and when the traffic exits the TOR network to connect to the rest of the internet, it is potentially vulnerable. The same goes for AWMN or Guifi.net—at some point the mesh network must connect to the rest of the internet if it wants to access the content there.

If a mesh network is going to be fluid and open, that can leave it open to abuse and surveillance. When it was announced that iOS 7 would allow Apple devices to connect in mesh networks, this was heralded as a game-changing feature. Indeed, apps like Firechat that allow chatting over mesh networks have become quite popular, especially in places like Iraq, where an internet shutdown saw droves of users picking up the app. However, the app makers were quick to warn that such mesh connections did not mean secure communications. If anybody can easily join the mesh and help route traffic, that does in fact mean anybody. And allowing even obscure access to anonymized data has proven to be as great a security risk as full access.

Any mesh network must use standard data transmission means: pre-existing phone lines and cables, WiFi, or other radio signals. While the mesh may route traffic around holes if particular pathways go offline, it still must be able to maintain connections. Radio jamming, cutting cables, or even shutting off the power grid can still shut down a mesh network in ways it cannot heal. The mesh overcomes certain vulnerabilities but that does not make it any more magical than the sum of its technological parts.

This is not to say that mesh networks have no value. Freifunk, a mesh network in Berlin, and the Athens Wireless Metropolitan Network (AWMN) in Greece were perhaps the two first widespread, public mesh networks. They were inspired as a way to improve the sluggish installation of broadband capable networks in their areas, and are still in existence today with a large number of nodes. Guifi.net, another mesh largely in Catalonia and Northern Europe, has grown to surpass them. Each node is just as capable of any other in shifting traffic around the network, and out of the network to the rest of the internet—but these meshes are partial meshes. Particular nodes handle the majority of the traffic. The topology of these mesh networks is like like a public transit system. It can't connect to everyone's front door, but tries to provide as many convenient stations as it can. (For further discussion of this history, and for a more thorough elaboration of the argument that mesh networks are a tool for democratization, follow Armin Medosch's book project in progress, The Rise of the Network Commons.)

Assembly of Guifi Supernode, Terrassa Spain. 2010. Via Flickr. Creative Commons license.

The mesh strategy, while not quite fulfilling the dream of the rhizome, has proven useful in these cases for adding customers a few at a time over a long period, not requiring the major investments of infrastructure that large ISPs require. Instead, customers can band together to connect themselves to the rest of the network—sometimes even laying fiber optic cable themselves to a new neighborhood or another few hundred meters down the road from the last node. There is a certain distributedness to this strategy, a way in which the overall organization of the network is more local and ad hoc than, say, Comcast or Time Warner, even if some centralization still persists.

Perhaps most important, the ability to experiment with mesh networks is a distributed, de-centralized skill. Using open source software like the router operating system OpenWRT, anyone with an off-the-shelf router can make themselves a mesh network, thereby developing a better understanding of the computer networks' function. And while this may not be a means to re-establish the internet on more equitable terms, it is a way that people can develop local networks that serve a small-scale collective purpose.

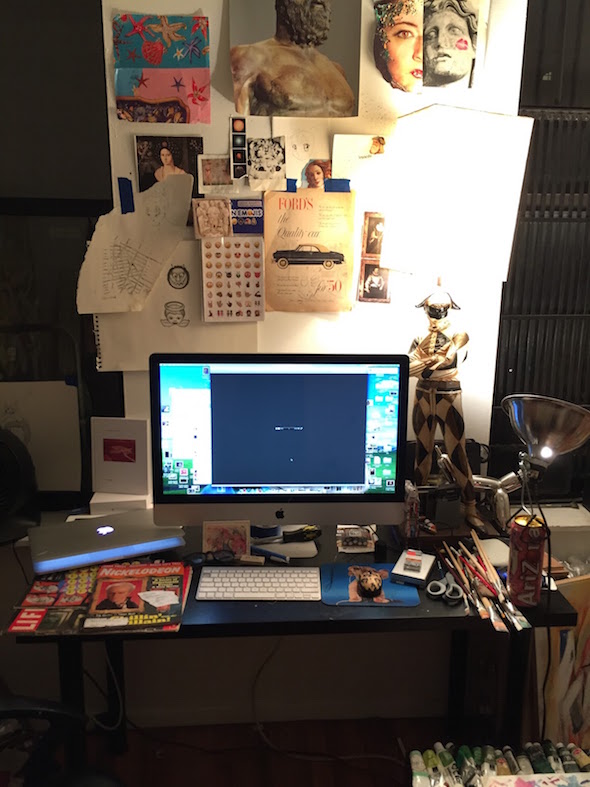

Eyebeam, an arts and technology non-profit based in New York City, has taken a particular interest in mesh networks of late, introducing them to the public via workshops and commissioning artsts to build their own implementations. The Internet Blackout Simulation at Eyebeam in 2014 was a series of workshops in which participants built mesh networks and tested them against potential failure scenarios. Their recent "Off-The-Grid" exhibition featured a number of mesh projects, including LittleNets, curated by Ingrid Burrington. For Burrington, the question was not so much of how to create a hardened network of resiliency, but of how to make it useful in the local context of the exhibition, held on Governor's Island in New York Harbor. "What do we put on this network?" she reflected. "What is useful on this island, in this space? I like the idea of using mesh for site-specific networks—they can maybe create a different experience for what we think of as 'internet art,' something more intimate. These nodes serve a different need than the whole internet." By carving out an area for artists to experiment with network technology, organizations like Eyebeam are not fixing the network as a whole, but opening up newer, smaller, localized spaces.

These localized spaces may serve social purposes even if they leave the larger network untouched. Centralized power structures are still in control of the primary networks. Open Mesh Project, a mesh network begun in Egypt during the 2011 revolution, appears to have petered out, from the appearance of their website. Occupy.here, a Rhizome-commissioned open-node network system run on OpenWRT created by Dan Phiffer and inspired by Occupy Wall Street, is still going, although the political movement that inspired it is gone, pushed out of the occupied parks by far less technological forces. Phiffer has had his open nodes included in art shows, like Eyebeam's Off-The-Grid, at the Whitney Museum, and surreptitiously without museum authorization, in the lobby of the MoMA. He envisions connecting these nodes together, but acknowledges that providing the connection is only the first step. "It's hard to be dropped into a new online social setting, and figure out how to use it. But in situations where everything else becomes broken, people are more likely to try new means to connect." He mentions that mesh networks had an uptick in interest after Hurricane Sandy. But also, at the Occupy Sandy response, the distribution of food and supplies trumped the distribution of internet access. "Occupy Wall Street was about creating the conditions to make people more likely to go out and protest, to express when things are messed up. Working groups were very important at Occupy, building the connections between people working together. How can we use technology to build those same kinds of connections that will make us more likely to get out and become involved IRL?" Perhaps mesh networks will be a way to facilitate this kind of local, collective behavior.

Dan Phiffer, Occupy.here router.

The NSA dips into any data stream it can at its leisure, and the major ISPs tighten their grip around the pipes and make network neutrality a distant dream. Overall, our networks don't function as a rhizome or a mesh, but a neatly ordered pyramid. But if we are to take Deleuze and Guattari at their word, the rhizome is not so much a steady state of being as it is a way of moving, thinking, and acting. The branching, ad hoc, horizontal ruptures are not the primary pattern of this century, but a way of reacting to the primary patterns of this century. Power exists vertically, and artists and activists respond horizontally. If this century is Deleuzian, and our networks are becoming like rhizomes, it not because they were already decentralized. Rather, it it is because they now must be, in order to survive.