![]()

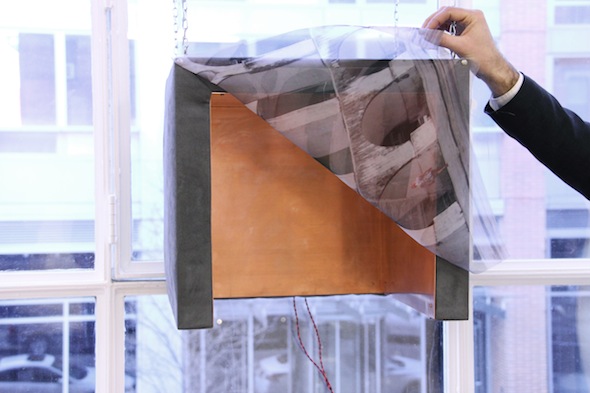

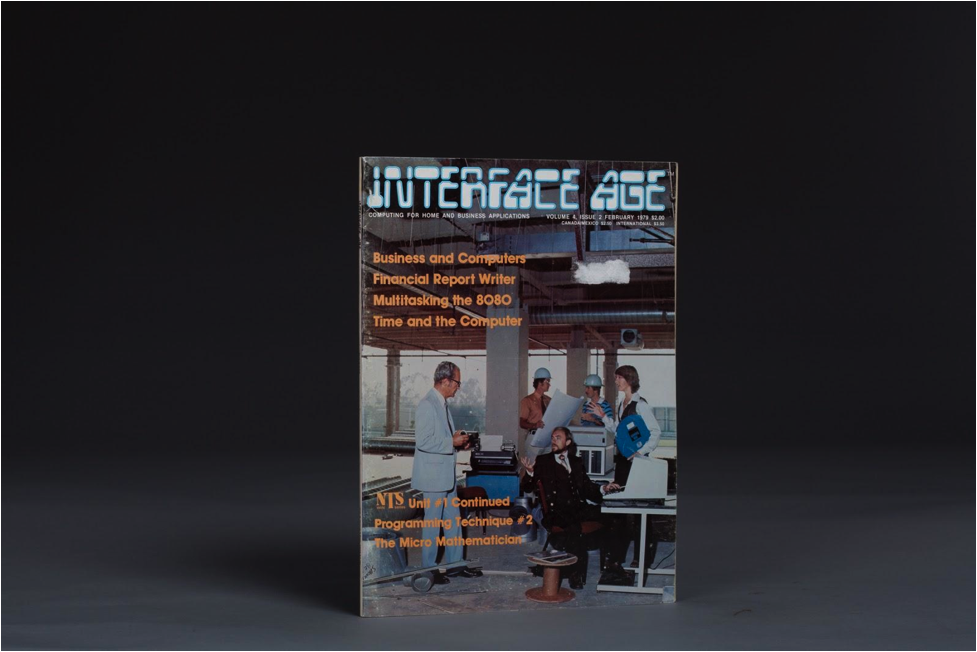

Sergei Tcherepnin, Ear Tone Box (Pied Piper Disappears), 2013. Microsuede, wood, zinc, silk, transducers, amplifier, iPod. Image courtesy Murray Guy. From a poster by Center for Experimental Lectures.

In January 2014, the artist Sergei Tcherepnin participated in a lecture series organized by the Center for Experimental Lectures at Recess. The evening was dedicated to investigating sound as an artistic material, both material and psychological, and also featured philosopher Christoph Cox. While Cox discussed the idea of sound as a pre-linguistic material, Tcherepnin took the opportunity to discuss an aspect of sound practice that remains largely unheard: queer sound and queer listening.

In this dual performance-lecture, "In Search of Queer Sound," Tcherepnin proposed that sound, and the process of listening, exists beyond pure materiality: listening as a social process, one that is not only natural, but also cultural. He suggested that much like linguistic comprehension, our perception of sound is socially coded.

Six months later, I spoke with Tcherepnin to clarify some of the points made during his lecture, to discuss some of his recent exhibitions, and to understand how the concept of queering sound informs his artistic practice, especially as sound continues to rise as an artistic medium and curatorial model.

***

July 31, 2014. Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, NY—Bedford Hills Café.

Charles Eppley: In your presentation for the Center for Experimental Lectures, you described the act of listening as being more than a physiological process, but one that is also socially learned and culturally constructed. Can you give some context for these terms, queer listening and queer sound? How are they defined?

Sergei Tcherepnin: I started to think about these ideas when I was in college. I was in an electronic music class that was made up of all guys. Later, I was in an analog synth ensemble that was all guys. Electronic music is historically very male-dominated, and there has obviously been a lot of discourse around women and electronic music, and there have been several books written. I started to think about sexuality and this idea of queerness, and separate from music, I was beginning to learn about queer theory.

I started to realize that there was not much conversation on sound, which in reality is very subjective... but normally it is talked about much more objectively. For example, even though a lot of the early 1960s pieces might have subjective tactics or strategies, like liberating the spectator to experience sound differently by walking around the space, there was still always an acceptance of sound as a pure, absolute material.

So, thinking about all of these ideas, I just wanted to question very simply: What would queer sound be? What could that mean?

CE: Is queer sound different than queer listening?

ST: Yes. Listening already implies the subject, whereas sound refers to just the sound itself. I started thinking more about queer sound, something so clearly not defined in terms of orientation, in a way, but then saying, well, what are different orientations of sound? Queer listening is about perspective…

CE: You mentioned that in college you were reading texts that questioned if, for example, there is inherently female sound, or women's sound, and in contrast whether or not there can be sound that is distinctively male or masculine; not so much sounds that assume a subjectivity after being heard, but those that have already attained an identity prior to being heard—a kind of preconditioning. Tara Rodgers published her book, Pink Noises (Duke University Press, 2010), which underscores (and at times challenges) the gender dynamics and politics of electronic music; and of course other articles raise similar questions regarding gendered sound and cultural listening.

Are there parallels between your work and such studies?

ST: I can try to be a little clearer about my approach and how this question enters into conversation with my own work. One of the last projects that I did, In Search of Queer Sound, is a video that I made with my boyfriend, Ei Arakawa, which starts with a question to a call-in talk show, an advice columnist; the questions are always posed by someone with a relationship problem, or something, but always a LGBTQ question. It could be somebody saying that their girlfriend just broke up with them, a teenager whose parents are religious and aren't accepting of them, and what should they do: should they run away from home? They feel like they're in hell. There is another one who is starting to date a guy who is HIV+ and he really likes him, so what should he do? Should he continue dating him or not? There is another guy who wonders about the ethics of gay bareback pornography, which is pornography of gay men having sex without condoms. Each episode of the video starts with one of these questions, and then we have taken out the answers given by the columnist and replaced them with a short answer in sound, or music. This process was a way to re-contextualize the music, which fits in some weird subjective, internal way; the process of subjecting sounds to these questions, inserting them into these conversations, was a way of queering sound for us.

Photo: Amy Mills.

CE: So by juxtaposing the sounds of an otherwise abstract modular synthesizer with these extremely subjective, outspoken calls from LGBTQ persons, this juxtaposition colors the abstract sound—it reorients it in some way?

ST: I don't know how exactly to put it into words, but that process made a ton of sense to us. Whenever I hear these sounds, I think about this man in crisis: thinking about dating a HIV+ man, this fear of HIV, and of infected blood… very subjective things. If that can happen for me as a listener, then maybe it is happening in the work to some degree, for other listeners too?

CE: We are getting into sound ontology, which raises some philosophical questions about what sound actually is. In this discourse there are two leading perspectives: materialistic and linguistic. On the one hand, there is an idea that sound exists prior to any lexicon, language, or ideology: sound as pure material. On the other hand, we also understand sound in relation to language and its interpretation: sound as linguistic. You challenge both perspectives by not actually falling on either side of that debate...

ST: Yeah, that is interesting. I don't think it has to be either/or… the idea that sound is a pure material is one thing I am reacting against, but it's also a given that I am starting with in some way. I think that is why I am in this in-between state—emotionally, psychologically, we are very affected by sound in subjective and irrational ways that we can't explain... the objective sound and the subjective response. We haven't talked much about Maryanne Amacher, but that is what I find so unbelievably beautiful and amazing about her work. She was always so objective in her process, but unbelievably subjective at the exact same time… an uncanny combination of a rational mind and this absolutely irrational decision-making, which came out of just listening.

![]()

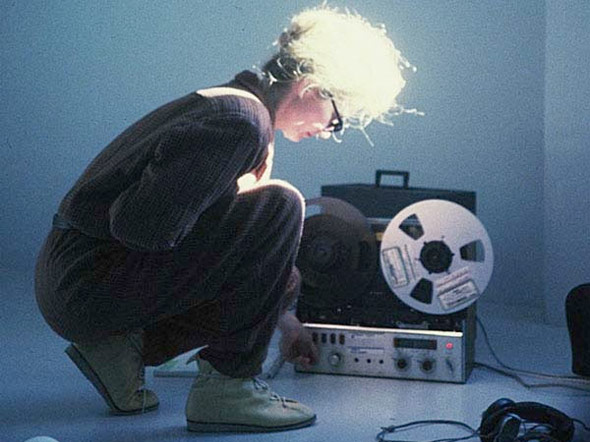

Photograph: Maryanne Amacher by Bryony McIntyre. Audio: Maryanne Amacher, Living Sound, Patent Pending.

CE: You are complicating the materialist/linguistic conversation by engaging this realm, which is psychoacoustics: a subjective response to an objective stimulus, but one that is pre-linguistic… as listeners we can have a sonic experience and our brains process that information in a certain way; it is cerebral, but we do not immediately contextualize or rationalize it. Perhaps this process can be learned, even re-oriented, and maybe this is where we begin approaching queer listening?

ST: Totally.

CE: Can you tell us a bit about your recent exhibition at the MIT List Center in Boston?

ST: The piece is called Subharmonic Lick Thicket. There are a few things going on in the title and the idea of the thicket… I wanted to make a kind of dank, swampy, thickly wooded area, full of sounding objects. The sounding objects are mostly based on tongues—tongue shapes of different sizes—and some are small, about maybe a foot long, and others are up to six feet long. There are probably about twenty tongues total in the room, made out of brass and copper. I wanted to make a kind of thicket out of these things, as if the tongues are growing out of the floor and walls. Some of the tongues are coming directly out of fabric, which is attached to the wall or floor, and some of the tongues and fabrics—mostly silk, chosen because it would look like tree bark, or in some cases animal skin, and also some synthetic fabric—protrude out of mouth-like shapes made of steel, which almost look like clams or Venus fly-traps. They are crude looking, in a way, and have hinged lips that flip up and down. Then there are tongues protruding out of boxes mounted on the wall at different levels: some are knee-high and some are chest-high; they appear to float with tongue-wings… so that gives an idea for how it looks. And then the sound: there is a series of what I call "licks," or short musical riffs—

CE:—like a guitar?

ST: Yeah, but they are all pretty much made on the modular synthesizer that I use—the Serge Modular—and they are playing through these tongues, so the title refers to both the musical material and the form that they take. [The Serge Modular was developed by Sergei's uncle, Serge Tcherepnin, in 1974 —Ed.]

![]()

Subharmonic Lick Thicket (2014).

CE: Is there a conscious relationship between the body and these objects?

ST: All of the objects are open to be touched: the boxes can be opened or closed, and the tongues can be bent up and down, but the objects are not simply interactive. In a way, I am trying to figure out how to indicate the fact that they can be interacted with rather than just saying they are interactive.

The sound will sometimes be on in one tongue, or box, but not all of the others, and wherever the sound is happening in the room indicates which work can be changed. You can obviously touch another work, but nothing will happen to the sound, because the sound is not on. I have made a kind of choreography, an orchestration, from one work to another—sometimes two at a time, sometimes four at a time, or sometimes just one—that indicates your movement through the room.

But it is not a necessity to interact with the work: you can just look at the show as you would any other show and hear the sound coming from one corner, while you look at another. But when you do approach a work that is making sound, or music, you can engage with it by really listening for what is happening; and then by touching it, and bending it very subtly, you hear the sound change and come alive. You are enlivening the sound, which might have otherwise been inert, and making it a live object rather than a recorded object. It forms a kind of bond through you, and it is a really intimate and bodily experience because you are touching the work and bringing it to life.

CE: So these brass tongues have transducers on them?

ST: Yeah, the brass and copper tongues all have transducers—actually, not all, because there is one giant, silent tongue that is just an object, or sculpture, and some smaller tongues. But most of them have transducers which turn them into speakers.

A transducer is basically just a speaker, an audio speaker, and you can play any music, for example, from your iPod or computer through a transducer, which basically turns the electronic signal into a vibration. When you touch them to another object, such as cardboard, glass, Styrofoam, or in this case metal—

CE:—or a subway bench…

![]()

Sergei Tcherepnin. Motor Matter Bench (2013). Wooden subway bench, transducers, amplifier, HD media player. Unique. Image courtesy Murray Guy, New York.

ST:—a subway bench, yes, it turns that object into a speaker. The sound from your iPod or whatever is amplified by the object that you attach a transducer to… on their own, transducers are very quiet and sound something like earphones, but when you touch its surface to another object, its material characteristics—density, thickness, length, weight—filter the sound in various ways. They have been used since the 1960s, at least, in a lot of experimental music—most famously, David Tudor's Rainforest (1968)—and in a way they are ubiquitous in sound art. [In Rainforest, a series of sculptural instruments are "performed" by various musicians who play sound through them via transducers, highlighting the specific resonant properties of each unique object. —Ed.]

CE: When the sound goes through a transducer and is amplified by the tongues, if a person hears the sound and they go up to the newly-minted speaker, which was not a speaker before because it only becomes speaker when a current runs through it—

ST: Yeah, exactly.

CE:—then they can actually manipulate the waveform of the original signal?

ST: The signal is always the same. You are just changing the mouth through which the sound is playing. It is really like in throat singing: when a throat singer sings a tone, and they change their shape of their mouth, they are changing harmonic structure, timbre, and filtration…

CE: Much like a trumpet player using a mute?

ST: Exactly. There are different analogies, but it is really a physical, not electronic, effect that happens to the sound. I think that is really important because the recordings are originally made of analog synthesizer, or sometimes physical actions or instruments, but they are made digital—and then you have these digital files, and when you play them back, they are made into a format; and to make them analog, or live again, is in a way what this work is about. The sounds are animated by these objects.

CE: Would you say they are revitalized somehow?

ST: Yeah. It becomes almost like a live performance every time you listen to the same recorded sound. I mean, that is maybe a dream that I have about it…

CE: Earlier you brought up the relation of this technology to work of David Tudor and the postwar experimental set. David Grubbs just published a book, Records Ruin the Landscape (Duke University Press, 2014), which discusses how some of these artists understood live performance to be un-recordable, in a way, because there was an ephemerality that depended on a spatial and durational context… and so they were resistant to things like audio recording. Similarly, we could never capture a recording of your tongues in action; it would not do them justice because the bodily affect is not preserved. On the one hand, you are working with this idea of sound-as-material, or the materiality of sound, which is a somewhat conservative concept in sound art; on the other hand, there is a representational aspect: Subharmonic Lick Thicket is not just abstract metal sound sculpture. You describe the objects as tongues, human or animal, and the idea of a thicket calls to mind a kind of setting… not a narrative, but rather an environment.

Tudor did something similar in Rainforest, but in that work there are people who perform with the sculptures, and the listeners weren't meant to manipulate his environment. They are able to in yours, and they are encouraged to do so…

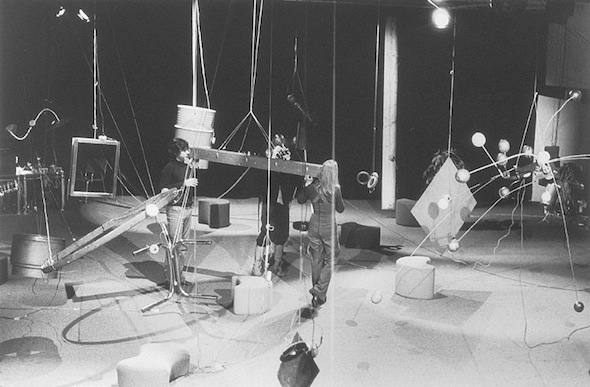

![]()

Paul De Marinis (left) in the installation of Rainforest IV (1973), L'Espace Pierre Cardin, Paris. © 1976 Ralph Jones.

ST: This is actually sort of tricky, the way that it relates to Rainforest. There are clear relationships, because Rainforest depends on feedback and the position of the objects in proximity to people and other objects, but I think he chose the title Rainforest because it is an ecosystem, and in a way, for me, the thicket is not a kind of ecosystem because the objects don't depend on each other. They are in conversation as in any exhibition of sculptures, but they are not codependent.

I want to talk more about this idea of interaction, because it is not required—in fact, I am trying to limit it to some degree. I find that when a visitor hears a work is interactive, they expect immediate results. These objects don't give immediate results. They allow you to learn how to listen differently, or change your way of hearing by deeply engaging with the work through touching. There are subtle effects, and the work is not dependent on interaction, but once you do [interact with the work], it brings it to life. In a way, it is a very sensitive work that is much more about intimacy than interactivity: the given is that it is an exhibition of sculptures; the surprise is that, well, you can touch them and get close to them. The way I would like to frame the show… well, there was an article in the Globe that said "this show is interactive" and the first day there were like a hundred people who came in who were literally shaking the boxes when they didn't make any sound: "this is broken, it is not responding to me," and not even listening. I almost had a heart attack because you realize that, in a way, audiences are not really hardwired to be sensitive listeners… Ideas are quickly lost; people leave my exhibition at MIT with huge smiles on their faces, they are having fun, and I am happy about that, but there is a lack of sensitivity. For example, I left the show for a week, and when I came back there were clearly places where people bent the metal to the point that one was completely broken. On the one hand, I am like, "Oh shit, that is vandalism," but on the other I also said, "Bend the metal," so I have to let go of it.

CE: We have been conditioned to act appropriately in galleries and museums, and to act in certain ways—namely, to not touch the art. But now you have these works that can be touched: "Oh, he says we can bend it!" So why not bend it until it breaks? Would you rather them not touch the work at all?

ST: I am bringing in the reins a little, but I am not pretending to make the work about some socialist ideal. Perhaps there are some ideologies built into the work, but what is more important to me is this idea of engaging deeply with listening—engaging the work through listening—and that is completely lost in just bending something until it breaks. Sure, you can do that, but I hope that people would teach themselves in the show, by listening, how to subtly engage the work. In a way, this idea of a thicket reflects this process: as a viewer, you are placed in a kind of foreign, natural environment, and you have to fend for yourself; learn how to deal with it. In a way, it brings out destructive or impatient tendencies, an unintended part of the work. Maybe I am being too pessimistic, and people are shaking things joyously, hearing things that I did not hear myself? This is bringing out my own ideologies and insecurities about the work, but that is good. There are a lot of issues that come up, especially in relation to queer listening, or queer sound. For me, that whole idea is built into a process of changing your perspective in relation to the work, or in relation to what a work can be, and I think that this change of perspective takes concentration, engagement, learning, change. It takes a change of perspective. In order to do that, there need to be some rules built into the work—not that there will ever be a list of things you can or cannot do, but it will have parameters.

CE: Perhaps this illustrates, in some way, a general lack of familiarity with sound work in gallery spaces. What is the reaction to an artist like yourself as sound becomes more prevalent in art institutions, and especially in the gallery context—large museums like MoMA putting on a show like Soundings, or even the 2014 Whitney Biennial, both of which you participated in?

ST: Well, I think that one thing I have realized is that when a curator invites somebody to do something time-based, usually it is video, which is more prevalent than a sound piece, they will know if, you know, it is supposed to be in black and white and there is a figure in green, or if the color is off, they will recognize it; if there is a scene is missing, if there is a corrupt file, they will know something is wrong. Their familiarity with learning a sound piece is so much more abstract, and difficult. I have found that I am often the only person who will recognize if something is wrong, even if it is a small thing, it is big to me. Unless it is something really big, like it turns completely off, but if something gets out of sync, I don't think the curator or attendants will recognize it. So, there is a practical problem, because in my case a piece might run for three months, and I would feel ill at ease to know that nobody there knows what the piece is in its entirety.

That poses a more abstract, or philosophical problem, this unfamiliarity with learning the structures of sound. There is often a lack of differentiation between one and another, where it all sounds the same, and that unfamiliarity poses a problem. It makes it difficult to do an in-depth show about sound, because there is a lack of understanding. I think there is interest, but there needs to be more education, or a desire to learn.

CE: Both of these exhibitions were rather significant moments in the institutionalization of sound art. What was your reaction to these shows? How did they address the issues of exhibiting sound?

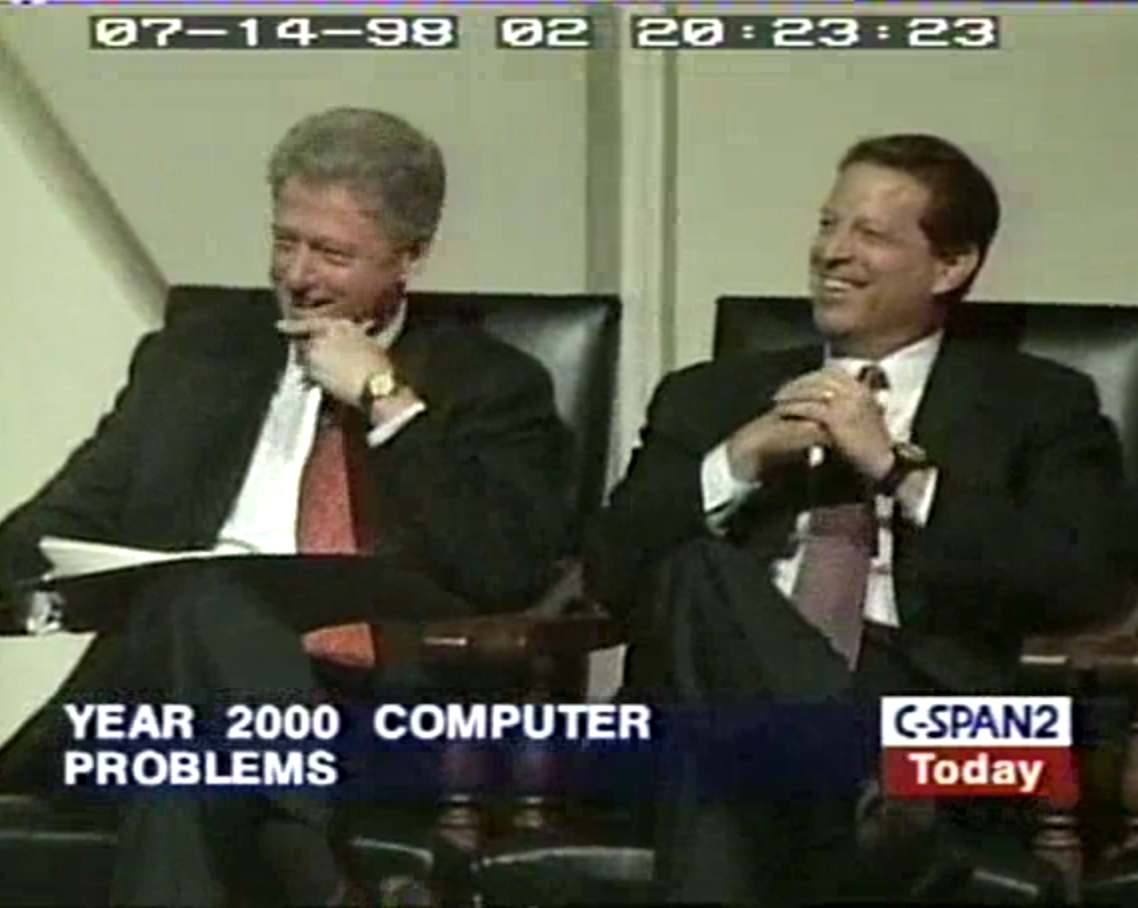

ST: Well, for the MoMA show, I showed one object that had a physical presence, as well as a sonic presence, and that was the subway bench with two transducers; for the Whitney Biennial, the piece was more parasitical, in the sense that it used the existing architecture as speakers, using the light fixtures that are used to light the lobby, so it didn't have a physical presence exactly—it was using an existing physical presence as a conduit for sound… both of them were playing with an idea of ambient architecture, and ambient music.

The bench at MoMA was placed at the top of the escalators, and for me having the bench on its own was sort of difficult in this setting. The bench was very popular, and people were basically always sitting on it—but I don't know if that was a product of the work itself or its placement, and the fact that people get tired at museums, and want to sit down. In a way, I don't think it did too much beyond, "Wow, this bench is vibrating, sound playing through my body. Let's move on." It kind of ended at that… I am self-critical about that point.

![]()

Installation view of the exhibition Soundings: A Contemporary Score. August 10–November 3, 2013. © 2013 The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

I do think when the bench was in my solo show at Murray Guy, it was extremely effective. It was still an ambient piece, and had the same sound, but it became a place to look at the whole show, and reflect on the show, and with the sound playing through you it completed this thing in a way.

CE: What else was in that show?

ST: There was a video of me as the Pied Piper, in, like, fishnet tights and a miniskirt with a floral pattern, and moving around an urban landscape under an aqueduct, or arcade, in Rio, Brazil. It was kind of like an urban, queer Pied Piper… there were lots of people around that I interacted with, but it was sort of an aimless Pied Piper figure.

Then there was a series of sound pieces: there were two boxes configured so you could sit on a little stool and stick your head inside, and a silk sheer veil that had an image of me as the pied piper that you'd be looking through. Every 10 or 15 minutes there would be what I call an ear-tone pattern, which sounds like two high pitch flutes, in either ear at a pretty high volume. To a visitor who is unaccustomed, they will just hear a lot of beeping coming out of a box... but when you put your head inside the box, I tuned the melodies [into] a pattern, in such a way that the difference tone created in your ear is a constant pedal tone, which is one note. As the two flutes are changing, and if you put your head inside the box, your ear creates a third ear-tone that always stays the same. It is a way of training your ear.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Above: Sergei Tcherepnin, Pied Piper Playing Under the Aqueduct (2013). HD video, 7 minutes. Below: Ear Tone Box (Pied Piper Recedes) (2013). Microsuede, wood, copper, silk, transducers, amplifier, iPod. 16 x 18 x 16 in. Bottom: Detail of Stereo Ear Tone Mirrors (2013). 2 security mirrors, transducers, amplifier, iPod. Each 12 x 12 x 5 in.

CE: You're talking about first order and second order difference tones?

ST: Yeah, so the first order of difference tones would be when you have two pure sine waves, like two flutes, playing one [tone]—say, A, which has a frequency of about 440hz—and then you have a second flute playing slightly higher—say, at 600hz, which is maybe a C—then your ear will create a third tone based on the difference of those two tones. So, literally 600 minus 440, which is 160hz.

This third tone is much lower and created by a distortion in your ear. People describe the phenomenon differently, but I am taking it straight out of a book by Juan Roederer, a physicist who wrote The Physics and Psychophysics of Music (1973).

CE: Is this a neurological or physiological process?

ST: Physiological, actually. First order difference tones are physiological: this is a distortion inside of your ear, in the cochlea. Second order difference tones are neurological: When you have an octave that is slightly mistuned, you feel a beating pattern, which is actually an illusion. That's how Roederer differentiates them.

CE: Which means that second order tones are not actually occurring? The ear does not perceive them through the cochlea?

ST: This is getting kind of technical, but, yeah, it is not that there is actually a distortion in the ear, as in the first order, but rather that the brain is making up this phenomenon, and then perceiving it. That is how binaural beating works when you hear I-dosers, which are sonic drugs, or brain-wave entrainment: you put a tone in one ear, and a second in the other, and then your brain makes up a complex beating pattern, which, when you change the speed cycle, is meant to mimic different brain states: sleep, excitement, whatever. People sell these things online.

CE: This is also a core technique of drone music…

ST: Yeah, for sure, someone like La Monte Young.

CE: And so the Murray Guy show used the first order, where there actually is a physiological distortion in the ear?

ST: Yeah, and, in a way, the boxes were almost meant to be training devices, which were juxtaposed with this queer Pied Piper figure. They really were like flutes, so it became this invitation for music, but [it was] also sort of menacing, because they were high-pitched. I did decibel level readings and they were really not at any volume detrimental to your hearing; it was all psychological.

CE: Noise in general is difficult to talk about in terms of, say, something like noise policy, and noise abatement—since the 1930s, for example, New York City has been combatting urban noise—because that designation is entirely subjective. Maybe this is tangential, but as we are talking about the coloring of sound, these themes seem to be present in your subway bench. Do you think some of this context is stripped when you show it in isolation?

ST: Well, yeah, there were some other pieces too [in the Murray Guy show]: there were subway mirrors that would come on every 30 minutes with an extremely loud difference tone pattern, turning the whole room into an ear-tone box; then there were these three very rusty rain shields that I took off of my apartment and turned into speakers, which were playing a very subtle sound piece through them, which became these speaker-instruments, but also these characters in this urban landscape…so, the bench can definitely work on its own, [because] it did not depend on those other objects, but showing it alone in Soundings did put pressure on the tactile aspects.

For me, the subway is an interesting place; on the subway people have ear-buds, so the bench became an interesting object in relation to how we listen to the world, and especially urban spaces.

CE: Let's talk about the Whitney installation, where you not only attached transducers to very iconic light fixtures, but also in a building that is no longer going to be the main home of the museum. You are using a readymade that is understood in a certain practical, or technological, context (a lamp, a fixture), but also one that is culturally-weighted: an iconic design in an iconic building. So, there is a technological baggage, but also an institutional baggage. How did this piece come together?

ST: Last year I made a piece for Art Basel, a whole booth for Art Statements by Murray Guy, and in it I made a giant piece called Cave In The Shape of an Elevator (2013). The piece was a giant box about ten feet tall with a weird door, as if a rock had fallen in front of it, and the whole box was covered in a blue-grey burlap and thick walls. [You could go] into the box, which could comfortably fit about four people, about the size of a normal elevator, and was lined with different kinds of metal. I printed large photographs of stones on some of the metal, instruments that I used to make the music inside, which [was amplified] through all of the walls. In other pieces, I've made speakers out of chairs, doors, using this kind of ambient architecture or furniture…

I have also thought about past composers dealing with ambient music, like Erik Satie, who made this sort of dry, sarcastic music that played with an idea of "furniture music," which ended up inhabiting a role that he was making fun of: you can now hear the Gymnopédie (1888) in the background of a department store. He went even further in a piece called Rélache (1924), which was a ballet—

CE: Francis Picabia…

ST: Yeah, Picabia did the set, but the music Satie wrote was so unbelievably vulgar to the public at the time, because it was all taken from these popular barracks songs; really, unbelievably bad music. It was this trash of music at the time, and he used it as the main theme of his ballet. So these ideas, like with the elevator, the doors, I wanted to symbolize this idea of background music in the architecture itself: the elevator as a stand-in for elevator music, but as a physicalization of the thing that makes it background; and rather than playing ambient music, I used the ambient structure, and played almost violent, physical music through it, reversing the idea of furniture music, or revenge of the furniture music. When you stepped inside the elevator, the music was very physical, because it was made from stones.

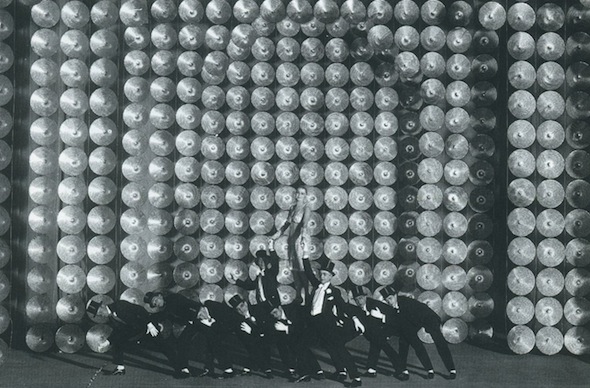

Anyway, Stuart Comer—a curator for the 2014 Biennial—saw this piece in Basel, and we had a long conversation about it, about furniture music, Satie, background music, the Pied Piper… [For me, the Pied Piper] represented the idea of violence against music as functional, a representative of potential for violence, the power of music, and the piper became this sort of queer figure, which ties into what we were talking about in the beginning actually. I talked with Stuart about [these ideas], and a few months later he came to me and said, "You know, have you ever noticed how much the lights in the Whitney lobby resemble the set of Rélache?"

CE: Ah, yes, the backdrop.

![]()

Relâche (1924). Ballet by Francis Picabia with music by Erik Satie.

![]()

Detail view of Ambient Marcel (Waiting, Working, Erupting), 2014 (E.2014.0114), by Sergei Tcherepnin. Whitney Biennial 2014, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, March 7- \May 25, 2014. Collection of the artist; courtesy Murray Guy, New York. Photograph by Bill Orcutt.

ST: Except instead of a backdrop, they are on the ceiling… It made a lot of sense to me, and it really was perfect. However, I underestimated how insane that lobby is, especially during the biennial, so it was difficult to make a piece that was effective during any time of day. I attempted to make a piece that reflected the different waves of amounts of people, during different times of day. During quiet times of day, there would be subtle, calm music, and during frantic times of day, it would get louder and be more active, as a very basic way to reflect its environment.

CE: How did you get this information? Did you study traffic flow in the museum?

ST: Yeah, but it wasn't anything concrete. I talked to people who work in admissions, and the bookstore, and they gave me times of day that were pretty precise, by the half-hour, which were the most busy, least busy. I made a piece that attempted to reflect that ebb and flow, and it was an ambient music piece, but it was also meant to change, and to have these, I'll say, violent moments that force you to listen, to deal with its presence. I didn't want to torture people, but I did want to have an impact.

I composed my piece during formal hours at the Whitney. I witnessed it with people in the room while I was composing—actually, assembling it, doing the balances—and it was more that the locations of the speakers were spread across the ceiling, which I was thinking about in terms of people. I was not trying to incorporate the sounds of the lobby into the piece necessarily, but recognize that the space was going to be filled with people. I wanted to have the sound enter people's consciousness, and I think sometimes it was very effective: it would be really quiet, and it would be as if, like, there was a little animal up in the ceiling, and I would see people look up, back and forth, and then move around the room. And other times there would be, like, some old lady who would turn to me while I was sitting on the bench, and be like, "What is that awful noise?" That would happen several times, and I had to deal, emotionally, with the fact that a lot of people hate weird, foreign sounds.

CE: Well, aside from a small label that was at the entrance—if you were walking into the lobby, you would not see it until you left—the piece was rather inconspicuous. Maybe people did not know that the work was actually there, until they were leaving, if they recognized it as a work of art at all? That is not a negative thing… actually, I thought it was one of the bolder moves of the show, to give so much room to a piece, so much weight by having it in the lobby, and then have nothing visual on display. I was reminded of Max Neuhaus and his interventions in public space, and how many of his sound installations were also unmarked. Neuhaus was not so concerned that people understand his installations as works of art per se, simply that they have some sort of genuine aesthetic experience.

In the case of your installation, if someone heard its sounds and said, "Oh, what is that awful noise?" then you have still succeeded as an artist, because you have made them think about how their perception of space is informed by sound.

ST: You make me feel better about it! You know, I think that it is a common thing for me, this in-between nature that you were talking about earlier, materiality and linguistics. I didn't want to make a piece that asserted its presence 24/7: the sound object that was living in the ceiling, like this Neuhaus piece, which is a drone that is always coming from a grate underground. I wanted something that would have a nuanced presence, one that was not easily definable. In doing that, I think that I gave up, say, my frustrations about friends going to hear it and saying "Oh, I didn't hear it, maybe it was broken?" I had to come to terms with that to some degree, but on the other hand, maybe there were people who came at 4:45 when it is this period of end-of-day frenzy, where all eight transduced lights are emanating this insane harpsichord swirling pattern, really, really dense. I am sure people heard it—they must have heard it, and ran out of the museum, thinking they were going crazy or something.

CE: Well, you know, in Rélache, there was that moment when all of the lights in the backdrop were switched on, and these fixtures, which faced the audience, formed a wall of mirrored, burning white light that thrust outward. The audience was blinded. I think there are similarities here regarding your approach to re-orienting sound: questions of materiality, linguistics, and the interplay between the physiology and psychology of listening, which seem to be recurring themes in your work…

ST: Exactly. This kind of switchability, a changeability, is good.

_____

Sergei Tcherepnin (b. 1981) is an American artist working in sound, sculpture, video, and other media. Tcherepnin creates sculptural environments and ambient installations that challenge our perception of sound. He has shown his work at MIT List Visual Arts Center, The Museum of Modern Art, Issue Project Room, Audio Visual Arts, Murray Guy, and the 2014 Whitney Biennial. http://murrayguy.com/sergei-tcherepnin/

Charles Eppley is an art historian and sound enthusiast living in Brooklyn, NY. He is a PhD candidate at Stony Brook University, where he researches the history of sound in modern and contemporary art. He works as an art critic and is currently a visiting instructor at Pratt Institute. http://www.charleseppley.com

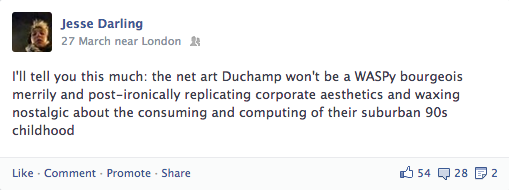

Martha Hipley, untitled Twitter hack.

Martha Hipley, untitled Twitter hack.