![]()

Work by Israel Lund at Eleven Rivington, June 2013

Do you follow? Art in Circulation

'Internet circulation has made all art look the same'

15 October, 2014

[Note: This is a rush transcript compiled by editorial fellow Anton Haugen. This document will be updated.]

Rosalie Doubal: This is the first in a talk series that we have been working on with Rhizome, "Do You Follow? Art in Circulation," and today, we are addressing the statement that "Internet circulation has made all art look the same." This is presented in partnership with Rhizome, and I am extremely grateful to Curator and Editor of Rhizome Michael Connor for his incredible work in producing this. Michael will be our chair throughout the series, guiding us through, and I will be shortly be handing it over to him. We are livestreaming today and we will be having a Q&A at the end. Thank you very much for joining us and thank you very much Michael.

Michael Connor: My name is Michael Connor, I am Editor and Curator of Rhizome, an arts organization based on the internet. It's a great pleasure to be back here in London, as a guest of the ICA. Rosalie has done amazing work in putting this all together, the whole team has made us feel very supported in what forms a major component of our Autumn program.

This panel is called "Do You Follow? Art in Circulation" and it kind of continues on from a panel we did with the ICA last year called "Post-Net Aesthetics." Before I turn things over and introduce our distinguished panelists who have joined us from places near and far, I thought maybe I would take a minute to situate where we are in that conversation and then bring up a couple of the themes that today's panel discusses. Each of the three panels has certain discussions that it's referencing. Today's talk is being livestreamed, which is I think why we are so brightly lit, so hello to viewers on the internet. I hope things are working well out there. All of us can use the hashtag "doyoufollow" to continue the discussion in social media, so I welcome you to do that in keeping with the theme of our panel.

As I mentioned, last year was the "Post-Net Aesthetics" panel that Rhizome and the ICA co-organized, which was curated by Karen Archey who did an excellent job with that. That panel was picking up on a conversation about the areas of practice of Post-Internet that had been widely discussed for several years up to that point. And I think you might be able to credit last year's panel with kicking off the post-internet backlash. Over the past year, we have seen a lot of angst build on that term, and we have also seen a lot of people criticizing it.

One of the things that has happened since last year's panel there has been an extraordinary number of different definitions of post-internet offered. Those definitions fall into three different kinds of groupings, all of which are valid because all language is made up, and so words can have different meanings. Thanks for teaching me that Zach.

The first definition is the market, stylistic definition that post-internet art is a kind of style that references the internet and is popular with collectors. The definition tries to trace it to aesthetic similarities or market trends in the art work. It's a kind of definition that has usefulness but it makes people feel depressed, generally. So that's one of the real reasons why this backlash has begun.

The second kind of grouping of definitions that emerged around post-internet would be the social and historical ones. Sort of between 2006 or 2008 and maybe 2013 or 2014, people were using the word "Post-Internet" at various places and times to describe different forms of practice or different communities of practice, and I think that definition is certainly valid. We have certainly seen people use the term in New York at different times with different levels of irony. There are different moments when it was picked up in London and reinvented and used in different ways. It also had different valences in Berlin as well. Los Angeles and San Francisco had their own kind of dialogue going. In all of these places, the term was applied in different ways and so there was a diversity of practices that were attached in this way.

The third way that people try to define Post-Internet is in the thematic way, where they try to find a certain philosophical basis that unites this extraordinary diversity of practice that has been attached to the word "Post-Internet." That is what most people instinctively begin with because one expects a term that seems so authoritative as "Post-Internet" to have some underlying philosophical kernel of an idea. That may not be the case, but there are arguments that have been made more or less successfully about that word and its thematic origins.

My own use of the word tends towards the social historical definition, but I do have some interest in the thematic definitions as well. For me, a lot of the arguments and discourse around Post-Internet that I have seen playing out have revolved around the phrase and ideas around "Digital Dualism." It comes from the sociologist Nathan Jurgenson who is actually a collaborator of mine on a series of Rhizome's "Internet Subjects." He defined "Digital Dualism" as a fallacy, believing that online and offline worlds are distinct, that we can think of an offline world or an online world or irl and url, that we can draw that distinction. The offline world is inherently structured by digital technologies, network connections. I think that is a true contention. At Rhizome, one of our core philosophical ideas is that the internet is not a sort of space at all but a process or a set of processes. Thinking of the internet in terms of a spatial metaphor at all is misleading.

Digital Dualism as a discourse is really connected to ideas central to Post-Internet. That there is online-work and then gallery-based work: the gallery, itself being an industrial model for circulating art work. Another way is in accelerationism, accelerating the contradictions of the system to an extreme position.

Returning to last year's panel, Ben Vickers' "Post-Internet is Dead (if you want it)," I think we can call that the beginning of the Post-Internet backlash, provided descriptions of a stance one might take in terms of a disavowal or refusal of the internet, to reclaim the idea that there is an offline space. On one hand we had this integration of online and offline space, while Ben Vickers wanted to reseperate the online and offline world. Also in that backlash space, we had the anti-internet art manifesto of Zach Blas and of course, Hito Steyerl's e-flux article "Too much world: Is the Internet Dead?" All of those were really interesting in manifesting different positions about the disavowal or working against the Internet. In addition to that, we had the Facebook study, where people learned for the first time, some how, that they were subjects of a large-scale social experiment, which is central to Social media. We also had the NSA-revelations, which were made possible by Laura Poitras' film-making and her ushering through of Snowden's leaks Glenn Greenwald, etc.

So a moment of extreme cynicism, and yet, I have not been this excited about internet culture since the dot com crash.

The panel came out of research we have been doing into, I suppose, well it started with our research on VVORK, because we have been trying to archive VVORK, which is a website which started in 2007; it was a very influential thing. All it was was a place where the contributors of VVORK would serially post artworks with just a title. They did use tags but they are not very visible unless you look very hard for them. They would never write anything, but you would start to see patterns emerging. They would post like five things about Michael Jackson when Michael Jackson passed away. There was this sort of implicit provacation that there was an inherent underlying similarity to what they post.

When it first began, a lot of artists responded negatively to the implication that a lot of art looks the same, that it was reducing artistic practice and that they were not giving the artist enough due. Making things seem very similar and depressing.

I think there was actually a kind of radical possibility in this presentation of similarity that VVORK gave us. To understand that, I think it's instructive to look at the next example, which came in between VVORK and Instagram as places where people would look at art on the web, which was Contemporary Art Daily. And here, we have longer post of multiple photos of a single exhibition with the press release. If the central contention of VVORK is that all art is this kind of collaborative process of authorship in which there's a lot of copying and ideas are transmitted back and forth and the individual artist as part of this embedded collaborative network of creative producers or of practitioners who are in some kind of dialogue, Contemporary Art Daily makes this kind of argument that the artist is somehow different and standing on their own and has something special to offer the world. That to me is more depressing than the VVORK perspective.

At Rhizome today, we are announcing back home in New York that we have come up with a new archiving tool, thanks to my amazing colleague Dragan Espenchied so [VVORK] is one of the first projects that we started to archive with this new tool. We consider the internet culture as process not space and in keeping with that, we archive pages as specific moments in time in which they are captured, and not as static pages which we download as files, so it's a different paradigm of digital conservation. That's what we're looking at here, VVORK on Rhizome.

But with this idea of VVORK and Contemporary Art Daily, I wanted to organize this panel to further explore this idea of sameness and difference, because in the past year it has been argued that all art is starting to look the same because of the internet. And we are to talk about whether or not that is the case. And if that is the case, if that presents an interesting set of conditions. So with that I am going to hand things off to Alex Bacon.

Alex Bacon: Thanks Michael. I am going to begin with perhaps the critically unpopular position, but obviously the one that inspired this particular panel which is "why does so much art look the same," but specifically in Jerry Saltz's case recently it was "Why Does So Much [New] Abstraction Look The Same?" He accompanied his article with these set of iPhone images that he took at an art fair. I think it's an especially kind of germane way of entering this topic in the context of Frieze week. Basically Saltz argued that the reason we are looking at this kind of work is not out of any kind of critical interest but rather the interest it has to a speculative, collector class.

I think that what's interesting is that it jibes with a perhaps more sophisticated argument by Michael Sanchez in Art Forum about a year ago ["2011: Art and Transmission"] that essential a lot of this abstraction was being almost produced for sites like Contemporary Art Daily, favoring of things like gray palettes and these kind of washed out images that would play well on the screen. But what I think that what's interesting is that [Sanchez's argument] presumes that there is this kind of power that collectors, dealers, and art advisors have over artistic production. It does not quit follow the timeline of a lot of the work in question because a lot of the artists who began working abstractly, the younger generation in the mid-2000s up to the present, started making work before this market boom. It's been difficult, to fully separate how much is related to the collector interest and how much is kind of in the aesthetic development, and whether or not that even matters.

Nonetheless, this certainly has then complicated further by creating this huge pool of artists. I often liken it to a kind of mall; everyone wants the Gucci t-shirt, but some people can only afford Old Navy, so there's kind of an artist for everyone. I think that's what I think Jerry Saltz lays out in his article, so I appreciate that.

I think an especially interesting focal point in this conversation has been what happened around Wade Guyton's inclusion in this Christie's auction recently. He was upset at the idea that his work was going to be auctioned, so he started posting on Instagram all of these photographs of him printing out this image, trying to emphasize the reproducible, anti-authorship of his work. Of course, this painting still sold for a record amount. I think it really showed that this collector class is more interested in having one of many paintings, rather than the original. I think what it also does is show us is [the collector's] relationship to the work; that they're being told almost by the work, what they want, so the seriality of the work has in turn produced this desire for multiples. Collectors, famously, are buying things in groups of ten, twenty, or more, but what I think that all this does is cloud the fact that the actual work, a lot of painting if we want to focus on that, of course, exists as an object in the world.

As a critic and as a historian (my background is in 60s and 70s minimalism, working with Ad Reinhardt and my dissertation is on Frank Stella), I can see certain of the similarities and differences. Looking at these things in person, some work stands out as an object. I really don’t want to install that difference between the online space (like an Instagram) through which this imagery circulates and then the paintings themselves, as if somehow they were inseparable because what I want to propose is that some of the most interesting artists working in this vein in fact embrace the circulation of imagery of their work, that they both produce work that stands as an object, but that they don’t go around saying “you don’t get it if you don’t see it.” You would say that, but at the same time, it has another life online.

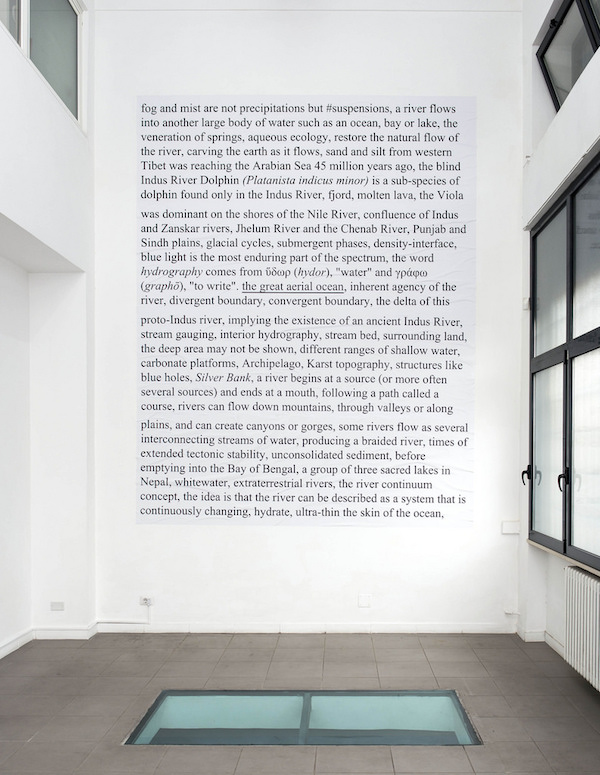

One artist who has done this in a smart way is Israel Lund. For example, here you see his show at Eleven Rivington from last yearwhere he installed four canvases in the window of the gallery. When you walked by you saw them from behind, and when you entered the gallery, you saw them backlit, very much as a computer screen. He was playing off this idea of something he calls “analog .jpg”; this idea of this hybrid status for this work that is produced in this analog-mode via silk-screening process but that he doesn’t disagree with its evocation of a kind of screen space.

But I think what is interesting then is to compare it to history is that, of course, some people like to compare his work to Gerhard Richter. If we look at these two things on a screen, they do look very similar. Experientially in space, they are very different. Richter is building up dense layers of paint that he moves around with a squeegee, so there’s a very tactile, physical quality to the work. Even though someone like Lund is discussed in terms of process, in a certain sense, there’s more visible process in the Richter. In Lund’s work, you have an image that is very hard to place. It’s much more an image that could only exist in an internet age: an image where its very seductive and beautiful, but there’s no way to find a footing for your eye in the work.

Another artist who works in this vein is Jacob Kassay. His silver paintings, especially, offer a very interesting commentary on this notion of perception and vision, this way we are constantly finding our identity through uploading and downloading images. Constantly taking photographs and uploading them on to social media, seeing other people’s post, it’s a way that we understand our place in the world and what’s going on around us; it’s very much a mediator.

What’s interesting about Kassay’s silver paintings is that as you move around them they not only reflect and absorb the light and the imagery of the space around them, but they do this in a very fragmented way. As you move in closer to them, your image becomes more blurred, and as you move farther away, it becomes clearer. It creates this kind of interesting experience where your expectation of being fulfilled by accessing this work is always thwarted.

Fragmentation is really something at issue in Jacob’s work as a whole. If you see his more recent series of works, which are based off of the left-over remnants of paintings: both his own and those of other artists, which he began by stretching up exactly as they were found. This idea of the incomplete or the fragment is related to this stream of imagery.

All of this for me, seeing the work of artists like Kassay and Lund and thinking about older generations, for me, what makes it different, I think that for these artists painting is related to the history of painting in modernism, you can’t deny that. I think it’s equally related to the surge of technological devices in our lives: smartphones, tablets, HD televisions; all of which have, unwittingly, have a relationship to painting. Painting is, in a certain sense, accessible to audiences today where abstract painting was the most difficult work historically; maybe museums showed it, these people were very successful in that way, but they did not have the kind of commercial viability they did today. I think it’s in part because we are familiar with this kind of rectangle. It’s something that acts as a frame for our experience.

What then becomes interesting for certain artists like Lund and Kassay is that they use this idea that maybe the painting becomes a momentary stop in the circulation of images. It’s not that the images are either in or out of circulation but that for a moment, they are held so that you can consider them and really think about what they are doing. I think in our current moment that’s a radical and important gesture. I think also important because it leaves certain of these questions that you were suggesting Michael; it poses them and makes them open. You really think about, “where is this image?” Is this an image when I see myself in the Jacob Kassay painting? Am I thinking of Instagram filters? Is it a mirror? What is this relationship?

Of course, it’s to all of these things;I think this questioning is very important.

Michael: Great. Alright, moving over to Takeshi.

Takeshi: Hi

Michael: Takeshi has just returned from Georgia, the Republic of. He has been experiencing some sort of cold, which he is almost recovered from.

Takeshi: I'm ill. Sorry. So if I stop coughing and splattering.

My name is Takeshi Shiomitsu. I am an artist based in London. I’m going to talk a little bit about what I do in my work and then talk a little bit about howI consider sameness.

I make work that takes up both digital and material space, often presented in the same series.

Last month I showed this in London, made up of five paintings and one video that was played out of sync on two screens.

Earlier this year, I did a show with Sandra Vaka Olsen in Copenhagen with Arcadia Missa and 68 where I produced a series called Pale History made up of video, painting, and sculptures.

I take it as a given that the experience of using the internet to receive most of the written and image-based content I’ve seen on an almost daily basis has trained the way that I read and see. Similarly, I consider that my production methods and gestures are inevitably informed by my experiences and exposures to different digital and physical platforms and modes of production.

Through a repeated exposure to certain aesthetic forms or display mechanisms we are unconsciously taught what to aspire towards. For instance, the sterility of the screen-based image seems to champion an objective notion of utility, perfection, or distancing from dirt, resources, and labor, etc. etc.

I consider abstraction to have some play as an alternative to the pragmatism of symbols and signs. Using the non-specific or borderline specific as a way to advocate different, possibly more nuanced ways of perceiving. Along side that, I make these relatively hyperactive videos containing quite loaded imagery, trying to have a more heterogeneous conversation, if you’d like.

I don’t think it’s possible to advocate one way of seeing or doing over another. I am trying to open up the various different ways we could be seeing to cross-contamination, infiltration, or at least, present a mesh of conversation. I consider sameness or homogeneity as a perceived trait, as a product to the various filter bubbles we are all participating in and that we are given access to by our real world subject positions. I don’t think widespread image internet-circulation really exists, but it is perceived within hermetic subcultures that have high rates of image-turnover.

In processing a stream of images online, just like in any other structure, we are led to uncritically accept a number of neutral, underlying contexts for what we are seeing in order to comprehend it. This could be anything from a digital camera’s white point to Cartesian dualism. For me, this can be expressed in the way that as people who seem to understand or know culture, at some point, we had to learn and are still learning as it progresses the cultural, historical canon. Our experience of culture is always modulated by shared cultural frameworks. To say it another way, our interactions are rendered within the confines of the user interface or platform.

The backlash against the nonspecific or unbranded manifests because its lack of objective signifiers in a society where objectivity and pragmatism is ideologically dominant. What we accept as a neutral point in order to gain access has a lot to do with taste, which is heavily informed by our subject, gender, class positions and the influence of our subsequent communities. It’s harder to gain access if you’re not coming from a similar subject position; the content has very little context.

So most often our tastes, the things we are drawn to, are led by an already entrenched belief system that’s fostered by our subjective experiences. Capitalism tends towards segmenting these varieties of experience and privilege into demographic groups of which there are an ever-expanding number with the internet. Sameness seems to manifest as a hegemony of taste within a decentralized power-structure, fore-fronting the taste of those who can afford the time to generate content or don’t need to work, or simply have a lot of energy for production. So it seems that often in image circulation, youth culture or wealth culture gets proportionally more play.

In effect, the image streams of each individual is formed by their own social, cultural, class, or subject position, in a decentralized form of canon with a hyperactive but hermetic turnover. The hyperactivity tends to overshadow the hermetic through exposure.

Browser-based internet culture is an extension of the real world preoccupation with pragmatism and signs. The distilling of information dance of already-known truths and codes would suggest the moment of encounter should constitute the entire consumption.

That’s it. I just wrote some stuff down.

Michael: Thank you. We are going to have the general discussion at the end, but there are already so many things to talk about. I am going to hand it over to Kari.

Kari Altmann: Hi, I’m Kari, and my presentation is called "Similar Image Haul: Genre as meme, #SAME so I know it's real." Hopefully some of you will know what #SAME means.

What is it that makes you fave something? Sometimes it’s something that seems exotic, sometimes it’s something that seems super relatable and cheesy, and then there are those magic times when it is the perfect combination of both. Instagram is perfect for these kinds of images; actually most image-sharing social networks are king of this image right now. For all of the kind of creative tags that people use to respond and organize these images, the most important one is #SAME.

#SAME is also how images are now found for you: added to your feed, allowed to stay there, recommended daily. We can also decide what is the same through our own posting and tagging. The internet allows for a lot of tropes and sames to be revealed and also authored. You always have related content to your content. If you search my name, you get this image from a tumblr. A lot of works from my websites come up as related content.

I wanted to insert this tweet that Rob Horning made maybe today or yesterday. "The pleasure of algorithmic identity is in how we can seem to change how we are through such small, convenient gestures." I really feel like the small gestures are important just through tagging, reframing, recontextualizing. The same way that digital artists used photoshop to make collages or final cut to make film, you can now make sets of content that have the same effect.

I have used different social networks to upload my art, but in 2008, I started using tumblr to make my own image sets, my own decisions as to what was the same. Of course it was open to faving, reblogging tagging, and replicating by others, which happened very, very fast.

But it wasn’t just the content, the color, or the actual objects they are replicating, but they are also somehow replicating the reframing, the vibe, the concept behind what I was doing. They understand it, and they understand the language of it.

After this project and a few others like it, I was really addicted to this process because it started gathering peers at the same time that it was gathering content. For every person that jumped in, it would multiply the content even more. So I thought what if we could keep this all together somehow, track in someway and include that as part of the process.

I tried to create a more meta-site called R-u-ins which somehow catalogued all of these different projects and all of these memes and then tried, desperately, to keep track of every single person who would re-blog it in a way that seemed like they got or seemed like they knew what was going on, people who were adding and auto-completing.

It kind of blew my mind that just posting a sequence of imagery something else could be communicated, just by grouping things together, again these small gestures that affect the algorithm of how we read these things. As the project progressed, new memes would come out of just collective activity, things that no one really started, they were just tropes. Because it was online again, it could be read as tropes and similar content again, and regrouped again and put back into the same sort of process.

Not only have I started other group projects like this, but I have also started organizing my own website in this way and my own way of working

So for instance, this is an installation based around similarities, an ambiguation of similarities, and it also has similar, related content. It is a series that is constantly growing through tags, through possible collaboration, and it changes every time it is put in a show or put on a page.

This is also a project commissioned through the New Museum earlier this year. This is the start of a brand new meme about mobility; it’s a content set suggesting that all of these things have a similar backbone.

This is my current website, this bar on the right are links to those kinds of projects, the ones I’ve shown you and a couple more.

Michael: Great, thank you Kari. Ok we will finish with Martine, and then we will move on to general discussion.

Martine Syms: Hello my name is Martine Syms, and I’m based in Los Angeles. I’m an artist also, professionally, a designer. Interactive, not usability. But it's close enough, it doesn’t really matter

Michael: Un-usable designer

Martine: Yeah I design un-usable things. My primary concern is really with publishing in the broadest sense of that: meaning both to make things public and also to create publics around different information. I have a small press called Dominica or Do-min-i-ca, if you’re American, I guess. These are couple books that I’ve published. The last one was from David Hart whose a photographer based in Chicago. This one is from me called New Guards.

A lot of that work I’m interested in how audiences are seeing a set of information or a set of knowledge and creating the meaning through that and what the relationship is to putting that out and how people determine it. I tend to use popular forms. This image is called “Most Days Film Stills.” Earlier this year, on a label called Mixed Media Recordings, I released a 12” record that I describe as an “audio film.” It’s a table read. There are five actors that read this science fiction script, but then as a part of it, I created this film still that goes with that. The audio and the script are published separately, and there was a manifesto published by Rhizome actually that also was tied into that, called “The Mundane Afro-futurist Manifesto.” It continues to circulate; it’s in the latest issue of Third Rail Quarterly. I sort of like to have all these different fragments that add up to an entire project that pick up different audiences along the way and also add to what the meaning of what that project is through its circulation and distribution.

This was a project I did over the summer, this was part of it. It was an exhibition called “The Queen’s English”; it was also a reading room, which took as a point of departure a book called Black Lesbians, which was an annotated bibliography by JR Roberts that was published in 1981. I gathered all of the books from this bibliography, and I also made two other bodies of work: one, the text piece is from the dedication. There were these text pieces that were the author dedications, and then there were images that I created, original images, that looked like they were from the time period of the other books that were in the selection. I think a lot of this goes to reading, what Takeshi started to talk about. I’m also interested in my own reading. I think the feed, how it plays into me, I like to show what I’m reading, watching and looking at.

There’s a digital theorist Lisa Nakamura who talks about computers as machines for unseeing; I think that’s something I’m interested in. I think most of the art that I’m really drawn to is not really considered art at all. Maybe I like to try to see what’s unseen that’s why I go between image and text a lot. I wanted to play that Trayvon Martin video a bit.

This project, "readingtrayvonmartin.com," it gathered all of the texts, articles, links, and primary documents that I was reading, creating this personal bibliography, following the case after the shooting of Trayvon Martin. There’s a sort of person behind this text. In terms of similarity, I think the internet affects me by creating these contiguous sites of discontinuity. They are documents like testimonies, but they are also editorials. They show how the story moved through the media. But since they’re stripped of metadata and contextual information, they all turn into the same thing.

Michael: I kind of want to move back through the panel at this point. There’s a key issue which has emerged that needs to be addressed more holistically. Before I get into that, I wanted to ask. You mentioned distribution being an important concept of your work, but in 2012, you published a different article on Rhizome called “Black by Distribution.” You talk about how cultural objects can become “black” in process of how they are received in the world, that it’s not an inherent quality of the work, that it is acquired through the process of circulation or reception. In this panel, the idea of all art looking the same is also a question of an essential characteristic of the work and another way of approaching it would have been through discussions of authorship and reception. Is the idea of “Black by Distribution” at play in some of the works we looked at?

Martine: Yeah, it’s definitely something I’m still interested in. I’m interested in the relationship between those identity markers in sort of the more capitalist demographics that are being created. In 2011, I wrote a book looking at film distribution, taking the history of race-film, films made for specifically black ghettos within the United States, how those distribution patterns historically influenced recent films, stuff that would be marketed as a “black” movie today. They really have a very one to one relationship. It’s a distribution that was set up through discrimination effectively and because the market continued that way or even if you look at something like R&B—

Michael: Right, but in those examples, the power to decide what something is, is not with the audience or the artist but with the person that controls the channels of distribution. Is that true?

Martine: I think in some respects I would agree with that, but I’m also interested in situations and especially in my own work— me controlling the distribution of my work as a part of assigning meaning to it and creating audiences for it that will add to that meaning. So creating works like books and records, but also films, where I’m actively involved in how it gets out into the world.

Michael: The question that I wanted to get to is that we have two people who have been speaking to abstraction in particular and two who have speaking to figurative work. I think Takeshi, there was something you said, an assertion that the internet has this desire for a utility of symbols and signs. Is it true that the idea of things acquiring meaning through distribution, does that only apply to symbols and signs? Is abstraction exempt from that process?

Takeshi: No not at all. I mean, the sign of an abstract painting comes back to the artist themselves. You see an abstract painting and end up going “That’s a Gehrard Richter from 1980 something.” That ends up being the sign of the aesthetic.

I think my issue around this thing of signs is that it does not allow much else other than the things that can be faithfully displayed within that context within the terms of a sign and within the terms of an objective truth or understanding.

Michael: In the kind of play of meaning that happens on the internet, there are certain concepts that can filter through and can be taken up. Not concepts but signs.

Takeshi: It certainly serves a purpose, the internet. I think there are certain things that can’t be encoded into a digital way of communication.

Alex: Something that you said that was very interesting was this idea that maybe virality is contained within subcultures that have visibility. It seems to me that that symbolism with that Richter, we have that association, is certainly an example of a certain subculture that can recognize that.

Something that interests me about Israel Lund’s practice is he really likes also maintaining a tumblr. He likes the sense in which images of his painting enter the internet, and he finds them resurfacing in some sixteen year-old’s tumblr in Japan alongside a pornographic image and a burning car. There’s this way in which it all becomes flattened. We have this understanding of his paintings or of anything, but even with Richter, I wonder how much any of us can control distribution. I think certainly a lot of these abstract artists also wonder because these collectors have been speculating on their work, and I think that’s also in relation to the internet that accessibility that we all expect now, that access.

Michael: The question of how the work is defined by distribution is interesting in relation to the examples Martine brought up, but it’s also interesting in relation to an abstract painter whose work ends up in the background of a portrait of some very powerful collector. The process of turning that artist into a marker of that collector’s status is defining that work in terms of that regime of signs and symbols. It places it in that value-spectrum.

Martine: But also participation in a sort gallery-system. Like if we look at Contemporary Art Daily, which has a pretty specific network that it operates within, that’s already inserting yourself into a way of distributing your work.

Michael: But I mean the gallery is the industrial model of that, and the Instagram of the collector is the digital version of that; it’s the internet version of that, whatever information economy we’re in today.

That’s why Jerry Saltz’s discomfort with the new forms of power that are emerging. Why this is particularly interesting because if you read it in an ecological sense, in terms of how these things are being defined through distribution, they are being defined in opposition in a way to that industrial-model of power derived from the gallery, which the critic was traditionally a part of. Now they are being defined around other forms of network, accumulated social capital on the network, which are not flat, but have a different topology—if we are going to indulge in one spatial metaphor.

Kari, it would be interesting to hear from you. What I respond to in your practice is that you are so invested in these forms of distribution online in a way that feels quite political.

Maybe we can talk about R-U-ins.org. That project can be a little opaque to me because it’s such a process-based project, but I like the description of it, that it is part of the catalogue. Through this tumblr, you kind of connected with this group of fellow users: artists and other people on tumblr. You developed this shared understanding to where you could post this image of a hitachi television showing a canyon and then it reappears in all of the other tumblrs of the people you’re working with, different iterations of the same thing. If Takeshi is interested in pushing against the language of signs, you specifically work with ones digestible by the internet. I wonder how you feel about his assertion that those things are circumscribed by a certain internet-logic. Or is that interpretation correct?

Takeshi: I think its an overarching cultural logic. I think it has a lot to do with economics and the scientific method and stuff like this… I don’t think it’s just to do with the internet. I think it’s more galvanized on the internet.

Michael: Let’s call it a cultural logic, which is quite visible on the internet. I think working in ways that people can respond to and can create these shared images that embraces this virality as a cultural mode we are in.

Kari: Or maybe embracing what Alex is saying where a painting ends up at the same level as a poor image. It’s like embracing that, promising that in some way. Maybe I’m not understanding your question.

Michael: In the works that Alex is talking about if there’s a way in which the image is trying to create a pause within a network of circulation. Where I see R-U-Ins working is there not so much interest in a pause. You create an image and you want to get something back and put it back out there and get something else back. It’s more of a model of participation in this process of things transmuting, getting bruised by the network, getting redefined in its distribution on tumblr. Maybe this is my imagination of your work…

Kari: No, I’m trying to figure out the right way to say it. Using the kind of templates for exchange that are already available and skewing them a little bit to change the meaning a little bit. That’s how the image is modified, into a content set. It’s understanding the things you’re talking about and tilting them a little bit. Operating on the same channel. Does that make sense?

Michael: That does make sense, but in doing that I think there’s something going on in your practice. It’s kind of hard to imagine your work as the background of a collector’s selfie. In terms of talking about distribution, Israel Lund is trying to address dual audiences and allow the work to be defined in distribution the gallery system and collector attention system but also play the tumblr game. You seem very invested in that tumblr community aspect of art.

Kari: I just love looking at that kind of imagery. I love looking at sets of content like Google image style things where everything is clickable. Like a set of profile pictures, everything is clickable. You could click the related links. I’m just really feeling it.

Michael: And then there’s something very collaborative about that where you are collaborating with machines, with cultural logics that beyond our control, and with other users. That’s a very collaborative model for an artist. Whereas I think with abstraction, it’s very rooted on a much more individualistic model. Do you think that’s the case?

Takeshi: Yeah, I mean yeah. I think art since Romanticism, all art is infested with individualism.

Michael: How do you constitute the individual in a networked age?

Takeshi: The individual is the same as everywhere just with a mode of distribution that is now slightly more infinite, like as an arm rather than a whole being.

Kari: What I love about these images is that they’re public and private at the same time. If you look at R-U-ins, it’s like people have individual accounts but are also collaborating in the content sets larger than us at the same time. It’s how the internet always is; they’re always open to being shared possibly the possibility that these private moments will be shared.

Michael: The internet is like this massive social experiment right now. There are so many aspects of that that are evil and insidious but so many aspects that still retain certain potential for different social forms to emerge because of this sense of connection.

Alex: I’d like to touch back on the point about individualism because I think what’s interesting about a lot of the work, just because we looked at them, Israel Lund’s and Joseph Kassay’s, though their work has figured as the backdrop for certain collector’s, there’s this sinister and perverse side to them too. In a way, the Kassay does not mirror back anything, it gives you this fragment. It points to this sense that we have been always given fragments, not that we ever weren’t but that we’re so aware. I think there’s a parallel connection between that work and to your work, Kari, in the sense of embracing it. It’s only in that kind of context that the collectors could like that kind of work. It does speak to this moment in that way. It’s really kind of sinister; they thing oh it’s this “beautiful color-field, it’s a mirror,” whatever. It’s not; it’s this chameleon, a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

Kari: When I think of Israel too, I think he is aware of templates. I think one of the biggest things the internet has done is made these templates obvious. Like there’s a million Michael Jackson paintings, that’s rich.

Martine: I first met Israel through small press stuff, so there’s also fluidity in terms of making that way.

Alex: So I’m doing this show that’s opening in Brussels on Friday, a little plug, but I have in it a video by Darja Bajagić, so the structure of the show is around Robert Motherwell’s legacy. What she did is when you Google search “Robert Motherwell Collage” and you Google image search one of these Eastern European porn sites that she frequents as a source of her work, you get very similar color schemes. Again that idea that these templates that something like the internet produces, even in the way it kind of regurgitates and organizes via algorithm something like Robert Motherwell…I think this kind of individualism has been drained out because of the internet.

Martine: Another thing about the template-ism of the internet, I don’t think it’s really a thing that the internet is creating. I think its certain patterns that are being created by commercial web. Like a template or a tumblr or google, even like app design patterns are already established beginning with Apple. I like that there are these private moments within the public. A lot of the forms I take come from a commercial world.

Michael: I think a lot of these conversations are coming back to Rob Horning’s tweet, in which he mentions “small gestures.” It’s some times hard to understand tweets out of context, but I think he’s being scathing about social media. That’s a little bit odd because there’s a long history of celebrating the small gesture as being a very important thing. You can put it as a de Certeau Practice of Everyday Life; everything we do is made up of small gestures. Right?

Kari: I think it was in a series of scathing tweets, but it was the one with a sort of silver lining. I always run into a problem of describing these tumblr-based works as art. They see it as a mood board or a set of faves. Most of us here probably know people who have worked in small gestures for a long time, just getting closer to tying that into algorithms and tags and genres and things like that. How small tweaks of the language can completely a set of content and how that is a mode of production in itself.

Michael: That’s interesting in relation to Darja’s work. There’s a growing sense among young artists, she uses porn, she thinks she can make a porn image mean anything or do anything. The image’s content has nothing to do with its reception. All of that conversation leads me to wondering, like the question of “Black by Distribution” in 2014, when a distribution happens on an apparatus which has one level of control and then it plays out through a system in which people use that apparatus to like assert different kinds of social capital or social power through the network, but then at the end of the day, it ends up in the hand of users who do not have very much power on the internet. And yet, they are still able to play their own game, redefining it, changing the codes of meaning. Nothing about this seems flat.

Kari: I love the way that online in general an image can exist in multiple sets of contexts in general; it doesn’t really affect your own. It can still be yours and still be sinister and sweet at the same time, just have a million different personalities or values I guess.

Michael: I think the question of authorship is interesting. We’re putting so much emphasis on distribution and reception, where does that leave the author. The other provocation that you made, Takeshi, that internet circulation is not widespread. It is fairly widespread at this point, but this is about the digital divide.

Takeshi: User interfaces differ from continent to continent. Screen resolution differ because people don’t have expensive screens in developing countries. What you find comfortable, if you feel comfortable reading the New Statesman online your reference points are different to someone who feels comfortable reading the Star online.

Michael: It’s not just the access to tools, which is how the argument is often raised.

It’s very much about society and education. It’s very much about class, your ability to gain access to worlds that you are unfamiliar with. It isn’t as democratic as the internet is supposed to have made it.

Michael: We’re going to move to audience questions. I see Jesse Darling’s hand shoot straight up. What have you got for us Jesse?

Jesse Darling: I feel like Takeshi and Martine touched on this a bit but what I am interested in is what you feel which work is not being circulated. Does the work derive more value, does it lose value, if it can’t be put online, if it can’t be distributed.

Hito Steyerl in her big manifesto talks about bodies moving through the fluid. It’s a kind of poetic metaphor, but it doesn’t work because bodies are not distributed that way. I think about the mainstream news what it covers, talking about Trayvon Martin and what is not distributed in mainstream news channels like what Taki was talking about. Aesthetic normcore has really spread. That’s really interesting, but what’s more interesting is what doesn’t. I’d like the panelists to respond.

There’s also this idea of your digital visual capital in general and what’s being shown and what’s not being shown. The trayvon martin piece, that story was not being picked up by mainstream media. I was following the story into one place, that was part of what was happening. I think some people can create value by not distributing things, but there’s that sort of imbalance of power in how there’s power in being silent or more power or depending on who you are, you just get ignored more.

At the same time, I believe in being very active online and vocal at things like this and present is for me a form of power, as is reading as is circulating the things that I’m reading, asserting different presences, and sort of looking through histories, that maybe have not been covered as much and trying to put these towards people who have not encountered these yet.

With the Queen’s English Project that was specifically these radical feminist communities, books that were published in editions of 200 that I was finding with book dealers, trying to reclaim it and put it back together. There’s a lot of work that doesn’t get seen and a lot of stuff that aren’t distributed. It really does follow predictable class, race, and gender lines.

Michael: There’s a very ambiguous provocation with that. My stance is to listen more carefully to like the Ferguson hashtag for example, which is to say these things should be circulated. The new digital dualist provocation that we need to be reclaiming this offline space and not circulating should be a stance.

Martine: Well Bell Hooks does that. She does not make digital copies of her work because it could be deleted easily.

That would be a relatively harmful approach to the digital dualist stance because a more productive approach would be to say “let’s not delete that stuff” and find ways to keep digital culture alive and accessible, which is the Rhizome stance of course.

Alex: It seems to me that certainly there are certain structural difficulties of certain kinds of work, ideas and positions being accessible. On the other hand, the over accessibility and access that people seem to have both in a kind of financial way and in an image way to content, how can they hold back. How can you draw that line? A lot of this is played around this kind of market question, but also the hyper-visibility of art these days, that somehow everything in the studio leaves. No artist is hiding under a rock anymore; every artist can have a website or a tumblr. I hear constantly that people in the art world, just go online and build these markets. Some people prefer artists with no background, with no context.

One idea for a show that I have is asking artists what would be an impossible work.

Michael: Do you have your C.V. to show as well?

Alex: My C.V.?

Michael: I’m just teasing. Sorry your show?

Alex: Asking artists what kind of work would it be impossible for you at this time to make. Everything from some kind of young artist who has this vision, that’s an old model, but also asking a very successful artists who has endless resources and access, how would you kind of stop?

This one body of painting by Parker Ito where he used Scotchlite. Where you couldn’t photograph the work, so he was trying to introduce this idea of what about a painting that can’t be photographed. Of course, they are photographed and sold. Is this just a dead question? The idea of the role of something like photography’s access to the work. In Parker’s case, the image still circulates, even though they don’t capture the work.

Michael: Is there anything that escapes the clutches? Or does actually everything escape the clutches?

Takeshi:What you’re talking about reminds me of I think it’s Ionesco, this play requires a 20-foot spider or something. This play can never be put on because there’s no such thing as a giant 20-foot spider. People have tried, but it’s not in the true spirit of the play I think in understanding the context of the digital, there are things you cannot represent faithfully or fully. Parts of experience that you can’t represent properly just in binary and digital through a screen or any sort of user interface or helmet or glasses or whatever. There are something’s that are not able to be represented; it’s a matter of understanding the structure.

Kari: I think of that question of a lot as it pertains. It can always be circulated if you want, even if it can’t be fully represented. It can be a mix; it can be a ratio.

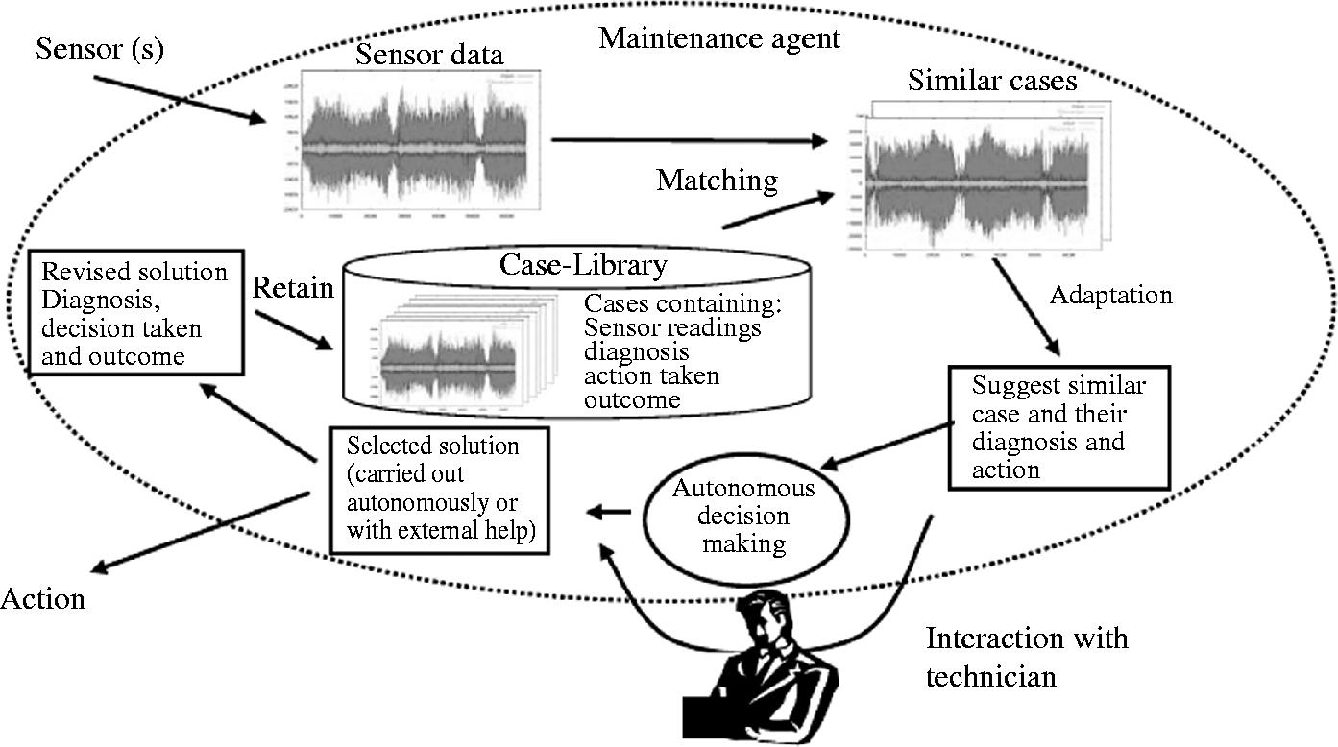

Olsson, E. & Funk, P. (2009). "Agent-Based Monitoring using Case-Based Reasoning for Experience Reuse and Improved Quality." Journal of Quality in Maintenance Engineering, 15(2), 179-192.

Olsson, E. & Funk, P. (2009). "Agent-Based Monitoring using Case-Based Reasoning for Experience Reuse and Improved Quality." Journal of Quality in Maintenance Engineering, 15(2), 179-192.

.png)