![]()

Do you follow? Art in Circulation 3

London, October 17 2014

Featuring Hannah Black, Derica Shields, Amalia Ulman

This is the third and final panel discussion in "Do You Follow? Art in Circulation," a talks series organized by Rhizome and the ICA, hosted by Rosalie Doubal and moderated by Michael Connor. This talk began with the polemic prompt that "Internet circulation changes bodies into image-bodies." A transcript of the first panel is available already; the second panel's transcript is delayed because of technical difficulties.

Rush transcript compiled by Loney Abrams and Anton Haugen. Discrepancies may exist due to transcription errors or unclear audio. Original video footage can be found here.

Introduction

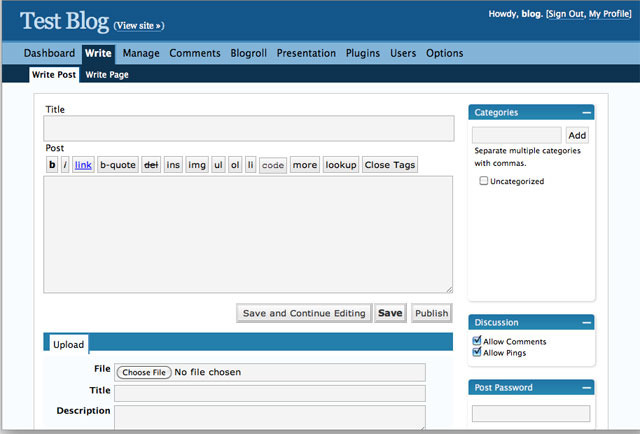

Michael Connor: Today's panel deals with the theme of bodies as— bodies and images in circulation. We are going to have a video by Hannah Black. The other panelists Amalia Ullman and Derica Shields will then join me on stage. Amalia will present her Excellences & Perfections performance, kind of the first real public-outing for that particular body of work. Derica will give us a visual sampler of the "Black Woman Cyborg," and then, we will have a general discussion.

This has been a really eventful week. This has been the most immersive, best research experience for me, personally, and I hope for some of the people who have joined in as well. The first panel began with questions of aesthetics and artistic practice, and how we think about aesthetic judgment when the work as a stand-alone entity is dissolving into this idea of the work as a circulating object. In the first talk, there was quite a lot of emphasis on opinions being statements of a subject-position rather than any sort of assessment of a work. There was also a lot of emphasis on the idea of disavowing, on resisting internet circulation, resisting being a part of media cultures, and developing alternative infrastructures.

In yesterday's panel, I was joined by Christopher Kulendran Thomas, Monira al Qadiri, and Constant Dullaart (who presented his rave lecture). Yesterday's panel had a sort of an accelerationist bent, although there was this interesting mix of accelerationism and sincerity through out. Monira al Qadiri used the phrase “give them more of what they want” to describe how she and the GCC came together around developing I guess an image of the Gulf that satisfied an accelerationist urge to understand the Gulf itself as a projection of Western or capitalist fantasies. At the same time, she presented other work that was personal re-writings of media images of her experiences of the Gulf War. There was an interesting play between responding to the demands of the flowsof capital and finding really specific locations within that. Yesterday was looking at the idea of place and location and how that’s affected by internet circulation, but it ended up dealing with markets, and in a way, that’s what locations are today, different markets.

Today we move from that idea of market-location discussion to a related discussion about bodies. Before, we do that here is Hannah's video Fall.

[Screens video]

[...]

In the description of today's panel, I used the term image bodies and that was a little bit of a flight of fancy—the kind I don't normally allow myself. The reason I used that term was because I was thinking a lot about Hito Steyrel's text about circulationism which was published in e-flux earlier this year, "Too much world: Is Internet Dead?" And in that, she talks about images circulating on a network becoming bruised, and the way she describes them is very suggestive of the idea of the image not just being of the body but the image being of itself a kind of body. So I thought that term described a more complex interaction between image and the physical structure of my body than representation or something along those lines. So the "image-body" is kind of a way of thinking of our bodies as partly image, and the images that we see online as partly body.

[Interruption due to technical difficulties]

Without further ado, I will pass this along to Amalia, who now has a functioning clicker with dongle.

Amalia Ulman

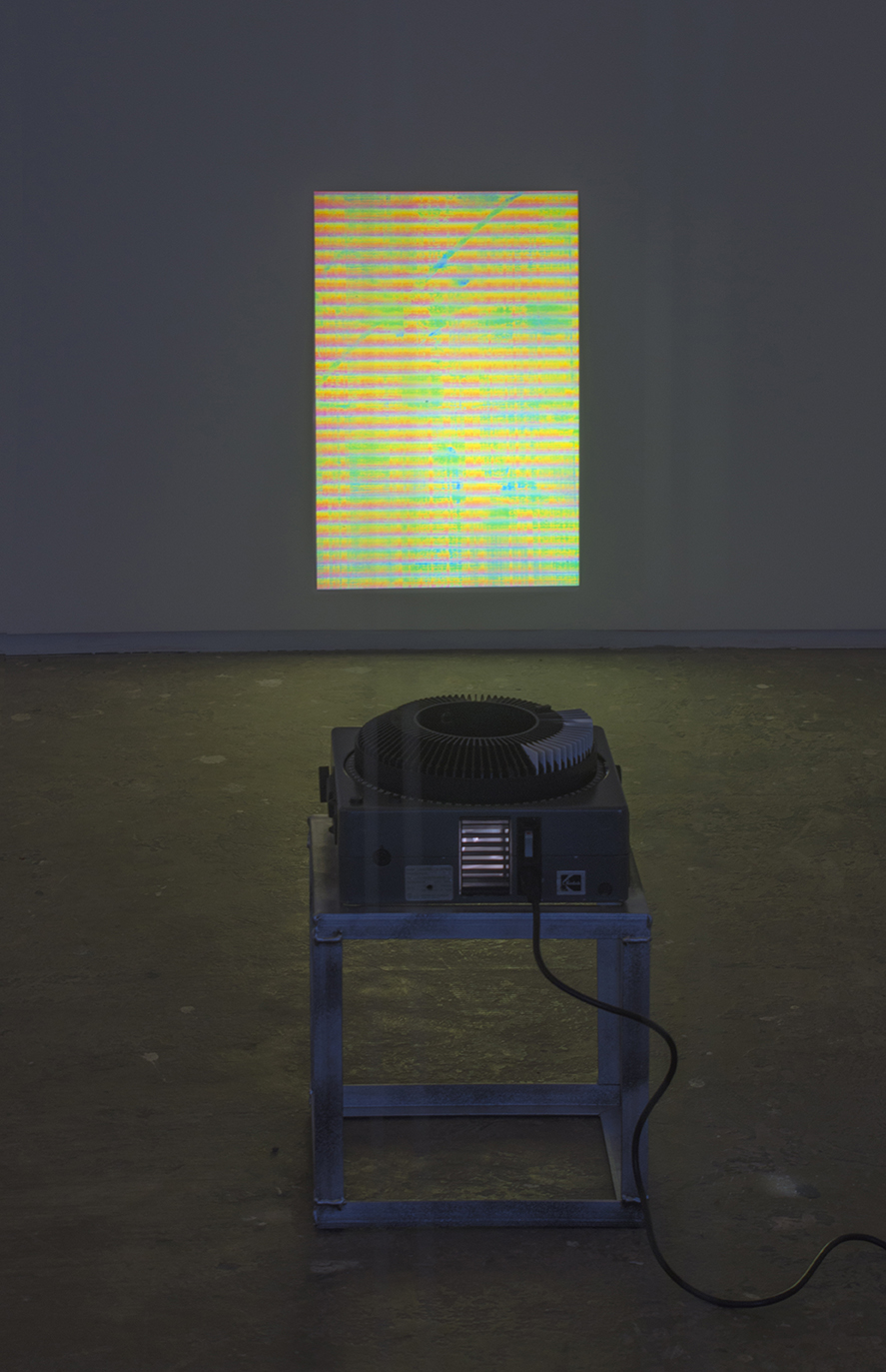

![]()

Amalia Ulman, Excellences and Perfections. Instagram.

Amalia Ulman: Hello. My name is Amalia Ulman and I'm an artist. In my practice, I observe social discrimination, class divide, and power structures. They treat her better because of her beauty and her money and her trust fund. That sort of behavior.

Preferential treatment

· VIP areas

· Bonus Points

· Executive club

I briefly focused these titles on research about objects: the life of ugly objects. The stories embedded in Chinese imports and how cities can be experienced through consumerism. The comfort of seeing the same wavy willow in some ghetto hair salon in my hometown and at the lobby of some five-star hotel.

But what about our bodies?

· Bodies can crumble, perish, disappoint us, promote us.

· Bodies can represent who we are, what our history is, where do we come from.

· We can't escape our bodies.

Bodies are suitcases for a consciousness, but who is this suitcase by? What label? Which designer? It could be a Burberry or a Kelly or a Vuitton or a Van's backpack or a Tesco plastic bag or a Zara tote. Bodies sometimes say too much, but bodies can also deceive, confuse us, disappoint us, misguide us. We can also manipulate our bodies and our appearances. Mostly through one single strategy: money.

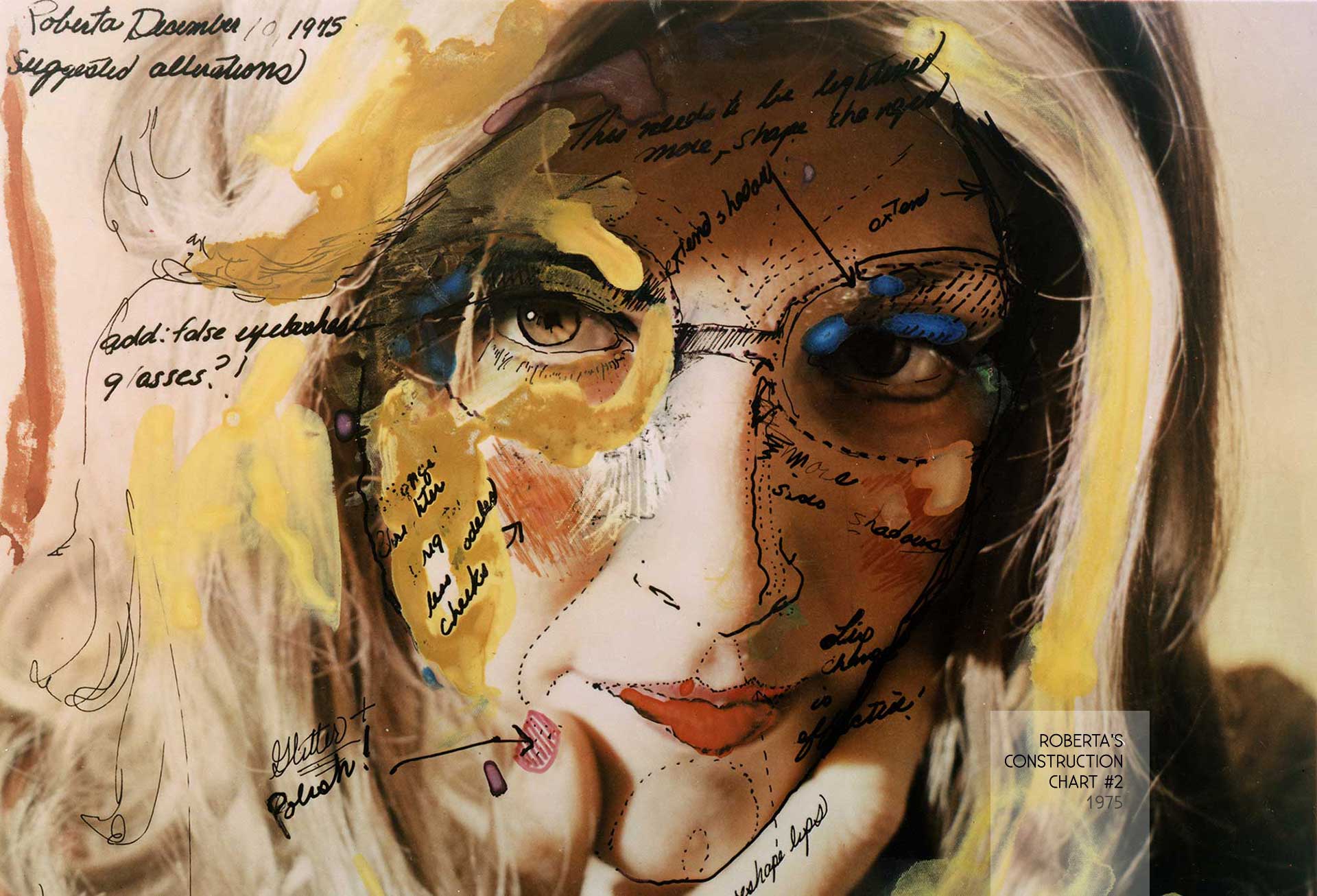

Excellences & Perfections is a project about our flesh as object, your body as an investment. How do we market this flesh? How do we price this meat? How long will it stay fresh for? Meet me at the butcher's.

In December 2013, I was invited to participate in a talk on self-branding. The term nauseated me. Was I self-branding? My openness had become a commercial strategy. No filter. I was unintentionally performing the stereotype of the artsy brunette, the poor female artist that had moved from a provincial town to the big city, the eager learner that requires to be saved by the male director of some museum or some school of fine arts. So if self-representation was an asset, if Facebook selfies overshadowed works of art themselves, I'd have to boycott myself to undermine the capitalist undertone of my online presence. Let the trolls in.

Even when you show it all, you reveal very little. The project would consist of a four month long performance, a full immersion in a screen reality. I manipulated the rhythm of my online presence/narrative to show how easy it is to manipulate an audience through images. My online representation didn't represent me anymore. For more than four months, I stopped myself from socializing IRL, except with those who knew about the project. Since May I'd follow a script, and all my posts were 100% fabricated. Inspired by all those Korean girls whose Instagram I check every morning and whose [unclear] I guess out of their daily selfies, I wrote a story in pictures.

The cute girl, smoothly mixing realities. The strategy was simple. I started with an aesthetic that was slightly close to my own taste to therefore appropriate the most popular It-girl trends on Instagram.

For the first episode, I'd go for cute, pink, grunge, blonde, LA tumblr girl, the indie girl who has only read JD Salinger, the American Apparel model, pastel colors, pink nipples, and rabbits. Cats, pale models, kawaii, violence, flowers, bondage, bruises. Only after one week of posting images in my new persona, the likes went up. Very soon, I started receiving messages from men who wanted to shoot me, the very phallic camera lens. I even received an email from a professional photographer in the line of Urban Outfitters and American Apparel. I accepted and I modeled for an unpaid photoshoot 'cause girls want to get their portrait taken for free, of course.

The model fantasy is probably the most widespread contemporary dream shared by young women of all backgrounds. Being watched means coming to life and being someone. The sadder the girl, the happier the troll. My main inspiration for this self-destructive process was Amanda Bynes. Trolls gorge on her disgrace. The sadder she is the happier is the troll, and that is what I wanted for myself. I wanted the audience to feel uncomfortable after desiring something that was inherently wrong, wishing others failure. But how would I make it credible?

People tend to believe whatever they've been programmed to believe. The audience easily generated the wrong narrative and conclusions after a series of proposed images that matches those in their mental archive of mainstream archetypes. The idea was to play with the notion of deception online, and my strategy was to rely on narratives seen online before, so people could map the content of the photographs with ease.

Money, boredom, malaise, addiction, self-esteem, surgery, the provincial girl moves to the big city, wants to be a model, wants money, breaks up with her high school boyfriend and wants to change her lifestyle, enjoys singledom, runs out of money, maybe because she doesn't have a job. Because she's too self-absorbed in her narcissism, she starts going around, seeking arrangement dates, gets a sugar daddy, gets depressed, starts getting into more drugs, gets a boob job because her sugar daddy makes her feel secure about her own body and also pays for it. She goes through a breakdown, redemption takes place, the crazy bitch apologizes, the dumb-blonde turns brunette and goes back home, probably goes to rehab, then she's grounded at her family's house.

I point out, in this episode, the popular sugar baby faux-feminist empowerment. I complemented the photographs with a series of statements I post on Facebook. These sentences were appropriated from the blogs and Tumblrs of real sugar-babies.

![]()

On Powerpoint:

Faux-feminist Sugar Baby Statements

[Facebook Status]

Amalia Ulman

31 July

guys who try to use the "are u on ur period?" as a way to end up an argument always amuse me. because it gives me the excuse to lean in n whisper: "i started me day by waken up in a pool of my own blood. is that how you'd like me to end yours?"

[Facebook Status]

Amalia Ulman

28 June

fun date idea: go down on me while I shop online with ur credit card see how many things I can buy before u make me cum

literally this

[Facebook Status]

Amalia Ulman

1 July

oh man the best is when a dude is like "u r not wife material" fucking good. i want to b totalitarian dictator material, blood sucking life ruiner material, fucking bulletproof immortal druglord material. not ur fucking wife u gross asshole

Being a former escort, I wanted to tackle this idea because as a feminist who believes in rights for sexual workers, the notion of empowerment always seemed really, really misleading. I believe in equality, and I don't stand for inverted sexism.

Reshaping the body

The only thing that interrupted my period of isolation was a talk I gave with Dr. Brandt at the Swiss Institute in New York. This was unrelated to the performance and closer to my research and the topic of blandness and middle class aesthetics. I was comparing the new trends in plastic surgery to my writings about the wavy willow.

For the further understanding of these processes, I underwent two procedures of this type myself. Under the guidance of Beverly Hills plastic surgeon Nima Shemirani, he modified my nose through his own standards of beauty and injected me with Hyaluranoic acid fillers in my cheeks and a drop of Botox[?] at the tip of my nose to not look like a witch when I smile. The latency[?] of these procedures was as a strategy for the fictional boob job to seem more believable. If the only public appearance was that of the talk, the audience would believe that which I presented to them.

Technologies of the Self

I've always been interested in the pain inflicted on women's bodies, especially how it's taken for granted, from Brazilian wax to liposuction, that female me-time is filled with sequences of little tortures. How would people, especially an art-audience, react to the female artist going under the knife? Better than I expected; the audience wanted more. The same as what happened with Amanda Bynes, everyone seemed to be on the encouraging side. It was funny how believable the story became, taking into account the bad quality of the images. The picture of me in the gown was taken right after a visit to my Spanish gynecologist, and the post-surgery photographs were all appropriated from different women. I supported the images with a surgery diary in the style of the plastic surgery website realself.com in which, unsurprisingly, the painful experiences are deeply infantilized. Under descriptions of post-surgical suffering are explained between lol's and funny hashtags like #morningboob, #frankenboob, #boobgreed.

I had excused myself from the scene to wanting to please, by using the "I do it for me" argument where "me" is pictured as a pure and precious innerspace, untouched by external values and demands. But isn't this "me" over-determined by a larger patriarchal structure that makes cosmetic treatment seem the only option for psychological survival in a world hostile to women's bodies?

I kept on training and going to pole-dancing lessons to make everything seem more realistic, uploaded videos to make the transition seem more credible, wore padded breasts filled with socks to keep the fiction going.

[Plays video]

Normalization via Coercion

When you repeat a lie, it becomes a truth, and a fake truth generated by images has more validity than a verbalized, genuine truth. Images are more powerful than words; it is hard to escape from the cosmetic gaze.

The trolling became more acute, and my fictional self was becoming sadder with the time. She was just trying to be prettier and perform the social role assigned to her at birth as a cis-female, but all she got was hate. The meltdown took place. The crazy bitch went into this black hole of depression, and her social interactions became weirder with the time. The crazy bitch got hurt; the bitch didn't trust no one no more, and she gets to her lowest point, and the audience loves it. No one says anything. Tears in this appearance, the crazy bitch, the former hot bitch, goes to rehab. Leaving some breathing space, in between updates, suggesting that I had been sent to a reformatory with little internet access. I waited around two weeks to post an apology.

The crazy bitch realized about her mistakes; she's sorry. This was an analysis on the archetypes of female-perfect behavior: calmness, virtue, discretion. The apology received 240 Likes, and I received messages from people that I haven't heard from in almost five years. People had been following in silence. I had succeeded in providing the most entertaining content: another human's sorrow.

The third episode meant recovery. The hashtags were #health, #juices, #interiordesign, #yoga, #simple, #family. I posed with a random baby who I had said was my cousin, posted photographs of breakfast I had never eaten. The narrative hinted to various ideals of perfection and salvation: Gwyneth Paltrow's Goop, Miranda Kerr organic cosmetics, [unclear] and yoga selfies. My life had been normalized. I was now a brunette whose boob job had been concealed under a flowery sari shirt.

I went on holiday with my new boyfriend; I had been saved.

Gaze as cultural construction

How is a female artist supposed to look like? How is she supposed to behave? How do we consume images and how do they consume us? Are we judgmental? Maybe? Or not at all? Or ABSOLUTELY YES!

All I know is that my words have less validity now because even my own real body and voice can be fabricated photoshop images. We live in the electronic economy of looking good; we all know the prices of your artworks will exponentially grow in relation to your looks and the likes on your facebook. But the good news is if human's perception is so malleable and the tools and the distribution of meaning and images have now been centralized, it's in everyone's hand to destroy archetypes, it's in our hands to bring the queer into mainstream narratives. If we can make our own porn, we can make our own romantic comedies too.

Slide: "FOLLOW ME ON INSTAGRAM"

Thank you.

MC: Well we have a lot to talk about already, and we are only just getting underway. Before I hand it over to Derica, I wanted to say that one of the things that's going on here, and we'll discuss it more at length, is there's a critique or an amplification or a working with the idea that we have these technologies for body manipulation and in some ways they become ways of replicating some social ideals or archetypes. So technologies that are meant to be liberatory are often employed in ways that are not. And there are many reasons why that's the case but its just an interesting note.

One of the artists that I was really hoping to bring over for this panel is a young artist named Andrea Crespo who has also done some interesting work on images of bodies that circulate in fan art and how those are radically manipulated in ways that are really different from the kinds of social ideals or archetypes that are at play in Amalia's project. And what's interesting there is that she also points out that those modifications are not necessarily liberatory but they have a much different valence than this.

But I wanted Derica to come along today to make a presentation—I invited her to look at this idea of the cyborg, or the body that has been modified by technology…But before I give away her presentation, I'm going to hand it over.

Derica Shields

Derica Shields: Hi everyone, my name is Derica Shields, and today, I'm going to talk about cyborgs, specifically, black women as cyborgs in 1990s music videos. Basically Michael and I had this chat, and I told him I was interested in the ways that people who are most vulnerable to premature death and destitution had imaged themselves as more than human, post-human, or cyborgian. And I noticed right now on Tumblr, in the types of networks I'm in, these images are being circulated, partly because the 90s are just in fashion, but I think also because these images seem to posit or pose some possibility, some imaginative possibility that I wanted to explore a little bit.

I am the co-founder of a series called "the Future Weird." As part of that, we screen films by directors who are black and brown from all over the world but focusing on experimental and sci-fi and futuristic films. So this is sort of part of that project in that I'm wanting to put together a screening that focuses on 90s visuals. So let's go!

Of course, there are some women working today who play with the idea and the concept of the cyborg. There's Janelle Monae who talks about herself as a robot, an android, a cyborg; Erykah Badu; and there's also famously, Beyoncé's video for "Put a Ring on it." In the music video and subsequently as part of the promotion, she walked around with this kind of cybernetic hand. But I was really interested in how the fact that the 1990s seemed to be this moment where a swathe of Black American, especially women artists, were experimenting with this idea of becoming something other than solely human or exploring the contradictions that already adhere to that category. This is TLC when they made the video "No Scrubs," which was directed by Hype Williams who is a very important figure.

So I guess before we talk about Donna Haraway a little bit I want to think about the social context of 1990s America. At that time Bill Clinton was in power from 1993 to 2001, and this is a moment when although he is portrayed, and portrayed himself I guess, and was received as this benevolent liberal nice guy who was described at one point as the first black president of the United States (I think because he played the saxophone of something). But he also presided over a massive change in the state of welfare and these were quite oppressive changes and they were predicated on a sort of, they really relied on this idea of black women especially, poor black women, as welfare queens. So there was this construction that had come down from Ronald Reagan and then there was this kind of bipartisan consensus during the 90s that welfare needed to be reformed radically. In 1996 something called the personal responsibility and work opportunity act was passed which basically introduced workfare, so you'd have to work kind of for free—basically for fre—in order to receive the welfare that you're already entitled to.

As part of this scheme, black women especially, were pushed towards taking any job they could find whereas white people who were receiving welfare were encouraged to seek further education. So this was just one of the ways black women specifically were being further marginalized and also stigmatized. So the welfare queen stereotype relies on this idea that black women are recidivist, terrible mothers, deceitful, manipulative, and will somehow trade their food stamps for like a Cadillac or something, even though its impossible. It's a very loaded idea.

At the same time as all of this is happening, so at the same time that the black woman's figure is being used in order to precipitate a lot of oppressive social and economic changes, there's also this concurrent swathe of black women performance artists and performers constructing themselves as strange creatures, which is what I wanted to look at.

So Donna Haraway is a well-known feminist theorist, and she understands the cyborg. In the cyborg manifesto, she describes the cyborg as a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction. It's also worth noting that her cyborg is often a woman or an ambiguously gendered creature. The cyborg for her is transgressive, and it breaks down a lot of the dichotomies between what is human and not human and organic and mechanical.

So let's get into it. So the first clip that I'm going to show is from Missy Elliott's "The Rain." Here we can see Missy in her massive black suit made of some amazing material and as the clip goes on, you'll see how she manipulates that material to change the shape of her body to alter how we encounter her:

I want to posit that one of the fantasies that we see manifest in this representation of black women as cyborgs is a kind of release into fluidity so a breaking down of the boundaries of the body; we see this billowing black jumpsuit that obscures her body but at the same time makes reference to the fact that she is a black woman who is too big to fit the models of attractive black femininity that are very narrow that are available. That would require her to be a light-skinned woman with fat only deposited in her breasts and ass and not really anywhere else.

So she takes this kind of designation and she blows herself up, right, she transforms herself into something strange and uncertain. I think that she refashions herself in some way as a kind of strange operation. In "Super Duper Fly," which is the subtitle of the song, I think she's playing with this idea of herself as some sort of fly. She's got the bug eyes and this encrusted helmet. She is rejecting the boundaries of her body but also the ideas that are layered onto her body by getting rid of this skin.

I think in this shot you can see how [director] Hype Williams' use of the fish-eye lens expands the space that is available for her body even further, because she's already big right? Like there's already the idea that she's taking up too much space, and she's a rapper, which then especially was not a happy place for women.

Next I'm thinking about Janet Jackson and I hope that these..they're not playing. They're just .gif's; they're not videos. Anyway, I can describe them to you. In the first, she just falls back onto her bed and then you see her apartment is this amazing chromed out thing, which moves all by itself. In the second, her hands falls down onto this sheet and her nails, which were already long, grow of their own accord and turn into these square-tipped, very beautiful 90s acrylic nails. And then toward the bottom we have her walking across, and her shoes transform themselves spontaneously.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Images via http://femburton.tumblr.com/

I think part of the fantasy that's in operation in this video is this sense of control but also invulnerability, so almost all of it takes place in this apartment apart from when she goes out surrounded by this cadre of girls. What I see happening is that her body is being created or represented as completely invulnerable but also profoundly self-sufficient. Where there were ideas of black women's dependency or over-dependency on the state, to an exploitative degree, she lives in this world in which she is entirely self sufficient. There is a strain of thinking about cyborgs that suggest that (I can read it to you)…Cathleen Woodword specifically writes, "the possibility of an invulnerable and thus, immortal body is our greatest technological illusion." But what I think is happening with the black women cyborg is that the invulnerability is not really geared towards immortality but rather towards survival and the ability to reproduced one's self without becoming exhausted. We see the kind of total realization of Janet Jackson's cyborg in 2008, which is also more standard, more sexualized—the sexy cyborg thing going on.

This is a clip from a Lil Kim video, "How Many Licks," and in this, Lil Kim represents herself as three different types of doll through the course of the video. It's such a complex video, and the lyrics are amazing. Its entirely about cunnilingus, but it's a clit-centered model of heterosex, which is really interesting, very forceful.

In that we see these dolls being constructed, we understand that her vision of sex in this is entirely about her pleasure. Each reproduction doesn't exist in relation to sexual intercourse; it only exists in that she has these dolls constructed which are all constructed in order to receive pleasure. So she doesn't exactly fuse the organic and the artificial, I think she's just more interested in how these are already implicated, how they're already part of the same thing.

At one point, words pop across the screen that say, "she doesn't satisfy you, you satisfy her," and for her, this is pleasure that cannot be quantified. It's infinite and abundant, but it's only for herself. So these are just my ideas about cyborgs and black women's bodies that I wanted to share, maybe we can talk about them later, thank you.

MC: Excellent, thank you. Hannah, we used a lot of our time already.

HB: Really?

MC: I mean collectively. That's something all of us did. Not so much you…no,no,no

HB: I'll read it really fast, because I'm really good at that.

MC: No, what I was going to say was don't read it too fast

HB: No, I'm going to. It's quite short, I think. This is a lot material, whatever, but it's funny; it's just for thinking.

Hannah Black

You asked this thing about images and bodies circulating and circulating through networks, so I've written a response to that. It speaks to some of the things other people have discussed. Anyway:

How did bodies begin to circulate?

Europe's adventures in colonial extraction established a vast global distribution network that shipped bodies, mainly African people, all over the world. These bodies were commodities that could speak and die. The money accrued from this enterprise built London and cities like it. The paving stones we walk on are cut from and the fabrics we wear are woven from the material from this only partly imaginable violence. This is not necessarily a matter of complicity, or of guilt, but only an observation about the texture of the world in which all images appear.

How did bodies begin to circulate?

The proletarianization of European serfs and peasants transformed them into the working class. These bodies were the bearers of labor power, the raw material of profit. The property and landlords instated at this time by the rich, exploded existing communities and impoverished and criminalized the indigenous people of Europe. The idea of national identity was forged in order to artificially fuse together these scattered and humiliated populations.

There is no true working class nationalism. The state is, and always has been, an attack on its people. Rather than being in an antagonistic relationship, national specificity and the network co-create each other. These two processes, bodies as labor power, the wage slave, and bodies as commodities, the slave, are deeply intertwined and richly dependent. Both also entail an intensification of sexual violence and patriarchal control as men are compensated by their own unfreedom by being gifted basically free access to women and children.

Of course, global communication predates the colonial capitalist enterprise. Long before the birth of white supremacy there were trade routes crossing Africa and Asia, hybrid identities on every coast like Zanzibar and places like that and so on. But the capitalist period begins by hurtling bodies into thin air to circulate according to the movements of profit. We use words like modern and contemporary to signal changes in the arrangement of meaning of images. But I wonder if we could put more pressure on these apparent novelties if we could situate the present in this long history of circulating bodies.

Hopefully, we are the last or among the last generations of a collapsing empire. No one will cry serious tears for the end of European bourgeois culture. It's the shiny surface of a world of shit. But in the meantime, we create proofs that we are somehow still living and we distribute them among each other. Like our ancestors who were laborers and slaves and servants and wives but still carried in themselves the secret of their selfhood, even as they were made into things.

We too hold the sharp object of survival tightly in our closed fists. The artwork, the pop song, the selfie, the shirt that looks so good on you, the kiss you still remember, the forgiveness of friends, the house party, the email that came at the right moment. The network in which bodies circulate is also, despite itself, the kaleidoscopic circulation of lives.

Discussion

MC: That's an interesting point at the end because I had been also thinking about how the word bodies has this connotation already of death, and that if we had talked about lives in circulation. I had thought about it more optimistic, but actually, that does sound quite pessimistic.

But I wanted to, because Amalia, you set out a kind of four-month arc there of performance. I think we should just start by reestablishing a couple of the facts, the facts, of that performance because,

AU: Can you play the video of the performance, in the background, very silently?

MC: Of course, is it easier to find from your folder? So basically, there's a few things that I wanted to amplify. Oops. One is that in that project you're essentially like everything that you, I can't really see very well with the lights but, um, can't trust a man with technology,

Everything that you've sort of posted on social media for about a four month period it from April to September was scripted. So there are all these different dimensions of it because I think in one way the project is pointing towards a sort of media culture of representation of cis-gendered female subjects who are kind of privileged or are aspiring to privilege, let's say.

But on the other hand, it exists within the social fabric of your friends and professional colleagues. On the one hand you're appropriating the experience of all these women who are kind of participating in the regime of cosmetic surgery in the selfie and in a kind of way that marks them in a way as privileged but maybe not the most privileged people. And on the other hand, you're kind of like trolling all of your friends. how did you kind of navigate all of this sort of complexity I guess?

AU: Even though it was scripted from the very beginning, like the three episodes and how the images would look like and how the behavior would be, it kind of developed because you see certain things started happening that made the performance richer. Like for example, the professional photo shoot, I never planned that. Or like the way people reacted to things, or like the messages I received, sometimes they weren't really what I was expecting.

MC: The moment when you moved into the apology mode, (I was following Amalia on social media) at that moment, I thought that you were disillusioned with the performance, and you were quitting. And I was like, "oh, she couldn't keep it up because its impossible." But in fact you're so rigorous that it's quite interesting.

People have expressed a lot of anxieties about this project and a lot of criticisms as well because for four months you looked like the worst person that we know or something. You looked like someone who was propagating this terrible image of cis-gendered woman. And so people that are in this room have this privileged knowledge that that was a performance and it was studied from a kind of world where that is actually, unfortunately, very common. One of the key anxieties, and a lot of men expressed this anxiety to me, is that then convinces other women to have a boob job or something because…

HB: That's not,, I don't think I thought that Amalia was a terrible person, I also found it stressful, but my interpretation was, which of course was totally wrong, I didn't know it was a performance, was that you were distressed or that you had an eating disorder, and I think that's a kind of a weird or specific thing to be like, this is a terrible person, whose

MC: you're right

HB: I know you didn't mean it necessarily like that, but uh, I don't know..

MC: Let's not say a terrible person but let's say a replication of a lot of problematic issues or something.

AU: That's one of the things, that's why I wanted to talk about the performance and be able to explain myself because it made me very anxious for a second especially with things like plastic surgery, which is an anxiety many women have, when you see someone that you respect or something, doing something like, give it a second chance or something. And I did receive some messages from girls that you like, you know, and I personally, I have no problem with plastic surgery whatsoever. I'm really into body modification.

The only problem is when things like this become a necessity when your body to become normalized and be part of this norm like how your female body is supposed to look like. Are your shoulders too wide or do you have hips or not. Especially because, in my case, I always paid attention to this female body shape because I guess you probably have the same thing that I feel that real Latina bodies are never really represented in media or real Asian bodies are rarely represented in the media. It's just like white body in like different shapes, like I would say, the same body structure. That's why I really wanted to have the chance to say that the performance was a performance.

I think that the plastic surgery thing was, why I chose it is because the main inspiration were all of these Korean Instagrams where girls have this obsession for beauty that we don't really have here yet. And it's like these daily modifications of the bodies where plastic surgery is really common and documented. It's like a status thing because it costs money like having a double eyelid the same way that the first Iranian immigrants in Beverly Hills just got a nose job, not because it looked good, but because it meant something. So that's kind of what I was looking for.

HB: There is a bizarre doubleness of simultaneity like, "you should look natural." Like I feel a lot of people write about this, like—a certain kind of man would say, like, "I love brunettes," like they're supposed to get some kind of— obviously they mean white women with brown hair and they want an award because they don't like blondes. So a certain kind of straight man tends to get a lot of personal satisfaction from not having sex with blonde women which is sort of weird since it's like, you should simultaneously be natural and authentic, but also look really great. I really like the example you gave of the tumblr thing of like messy high buns and it's like a black woman doing a messy high bun, which obviously you can only do if you have straight, straight hair—

AU: I was always very much into the idea of "fake natural" especially because I come from Spain where the artificial is always very stigmatized. People still go to the gym a lot or do all these things but it has to look natural because it's like we are against Americans and so everything has to be low key.

I mean one of the main points of the performance was because I had been so objectified before without really wanting it, just by being myself, in a way, like not really wanting to be objectified. It was kind of like a role-playing game of seeing whether I was being accepted as a female artist to look like or not. Which is something for example that I always really liked about someone like Petra Cortright who also plays around with dumb blonde aesthetics, which pisses many, many people off because female artists are not supposed to be or act like that.

MC: It's interesting that even in my preamble, I was expressing this judgment towards people who are responding to a system in which like extremely small differences mark bodies with very different values.

HB: There's this idea that youre objectifying yourself, but if you take it as a given that you've already been objectified by the surrounding culture, then the question of self-objectifying becomes kind of different.

I think that comes across really well in the sort of cyborg African American women or whatever. If you start from "you are an object," which women, and especially black women or women of color do, then it's like "well, what are you going to do about it?" You could desperately aspire to some kind of human authentic identity, which in some ways, you are never quite going to be allowed to have. Or you could go straight full bore for this "I'm going to be the best kind of…" which [to Derica] I don't know if you read that…

DS: Yeah, in the Lil Kim video, her self as commodity is the horizon. That is the possibility. That's what she is and what she is aspiring to. She is very aware of that. The video was not well received by many because people already felt that she was pandering towards this idea of herself as commodity. I think she's saying "No, this is just a loop. We don't go anywhere from here. This is it." It's kind of a bleak place.

AM: Maybe the idea is making it so obvious that it becomes disgusting, and people really realize what exactly is going on by exacerbating it instead of doing "the natural thing."

DS: Right.

MC: It's interesting because when we met and talked about this panel, I thought you were going to show a different segment of media culture in which the cyborg was assigned a lower social value, that the cyborg was the first soldier to die.

DS: That image of the cyborg has definitely been part of the screenings that we have done. There's a film by a British filmmaker, Kibwe Tavares called Robots of Brixton (2011). In it, the cyborgs have basically taken the place of immigrant populations, so they live in Brixton. They do all the most menial jobs, and there is a riot, which is then folded back on to Brixton riots as they have occurred in recent histories. That is a really interesting point to look at the cyborg. I guess I was interested more in what do people who experience, who know themselves as part of a demographic that is already disposable, how do they imagine themselves through technology? What kinds of fantasies emerge? And how are those…And what kind of bodies are displaced by those fantasies? What kind of bodies are rejected? And what kinds of bodies are created?

HB: I think it's also interesting, I think a lot of this stuff sort of conceals, like what you were saying, making something so evident that it becomes disgusting. I think there are a lot of efforts, ideologically or whatever, to prescribe that to a sort of—

For example, how sex work can be very horrifying to people, but there's always some kind of exchange especially in heterosexual relationships. Like the deal is, you put up with quite a lot of shit, like for most women in heterosexual relationships, in order that then you have someone, especially with like a middle class white man who is probably going to be like, you're probably going to have a nice apartment. This is my personal favorite thing like sometimes you have a really nice apartment if you have a rich, white boyfriend. But that's not supposed to be—

AU: [Laughing] That never happened to me with my white boyfriends.

HB: Ohh, I'm sorry. Well…

MC: So, paid sex work is…

HB: Well maybe I can find you another one…[Amalia and Hannah laughing] But I think it's interesting how you're not supposed to say that's why you're doing it. So you're also just spontaneously… So Petra Cortright does this thing, which I also find kind of annoying, but then, I sort of checked myself for it, when she's like "Oh, I'm really into my wedding registry and planning my wedding." Of course, I also recognize the kind of cultural edict that everyone should be in a relationship, like it's fucking tragic if you're a woman whose not in a relationship, especially an older woman. Like even though people shit on Tracy Emin, she's quite cool in that she's like "I'm single! It's awful." I love that she does that in public, even though, she's a horrible Tory and stuff like that as well.

I just think it's interesting thing where you're not supposed to say what the inner logic of things are. You're supposed to pretend you just happen to be doing exactly what you are supposed to be doing.

AM: That's one of the things I really wanted to talk about in the performance. It's like I have this fictional boyfriend, and everything in the end revolves around that idea... So I break with this boyfriend, and this is why this happened, and then I get into relationships with rich men, which are my sugar daddies, and something else happens, and everything is because of this male figure there. At the end, I go back home and everything, and then, I have a new boyfriend, stylized again, this idea of being saved, which is like something I had to deal without me wanting it because of the female artist sterotype, as well.

DS: How do people who comment respond to your various boyfriends?

AM: When I split with the first one, they were like "Oh, he's such an idiot. You'll be fine." With the new one, they were confused. The break-up was funny because I was like sad and going on dates again and dressing up and doing all these things.

[Michael's microphone doesn't work]

HB: Should I do an impression of you?

MC: Should you do an impression of me?

HB: I'm Michael Connor

[Laughing]

MC: I don't think you can speak slowly enough

HB: No, it's just dying out.

MC: I think the way—What?

HB: Sorry, please continue.

MC: It's getting more and more difficult by the minute.

But, thinking about the positions that are being staked out... I mean, the narrative detail of your [Amalia's] performance is so rich, we could talk about that all day. But the positions are interesting because— I like the way Hannah described it, like you accept the terms that your body is a commodity or object, and what do you do with that? In Amalia's case, there's a different set of options at her disposal and an intent to move that to the nth degree. To return to your [Hannah's] video, I think your video is moving towards a disavowal of the body.

HB: I think we talked before about how it's really interesting this idea of abolition of the body, but then it sounds like I'm really into the singularity, or whatever that thing is where people upload themselves to the internet and everyone is happy—

MC: But it's like a void or a negation.

HB: Well I think that's why I thought it would be interesting, in terms of an image-body, instead of presenting some kind of surface of a body, it's supposed to be this kind of internal—I was actually imaging one body that transforms into lots of different kinds of people—the idea there is this sort of mutability of those kinds of concepts of the body.

I think that came out of a whole set of thinking, which is maybe a bit dubious, but this idea that the body as we know it is kind of inventedwith these two big historical moves, which I mentioned in that short thing I read out.

Wage-labor: Where the body becomes the site of your labor-power. The thing you sell when you go to the capitalist and go "Please give me some money, so I can pay my rent." You're like, "I have the capacity to work." So that's one way in which the body is given substance in the world.

The other way is the body literally as commodity. There's this long tradition of writers on the idea that Silvio Federici writes about, that a lot of people write about, that as men are proletarianized and taken away from their own means of reproduction, it's like "don't worry, you can have women!" So women become a common resource between men. These are broad historical gestures. They at least suggest the body is this complex thing that is historically formed.

If you met someone from— I don't know, whatever, I can't even think of a period in time— 400B.C. Oh the body! You might share the same kind of appearances but we might not share, possibly, the same concepts of what a body signified.

Another thing I think is interesting and is tied to the whole post-internet or whatever, attempts to grasp the contemporary, which I think are kind of worthwhile. Thinking about patriarchy and white supremacy complicates these attempts to periodize a little bit, then you don't have this post-crisis, precarious, post-2008 capitalism, what you have is a continuous assault on basically everyone who isn't a capitalist. That has literally been going on since the birth of current social order. So rather than "oh my god there's this bank crisis and it's gotten very precarious and bad, and some rich people don't have as much money anymore." Maybe people who weren't rich but had more access—

Anyway, it's not to throw out the window that things like the internet have not had particular social meaning and make particular effects on our behavior. Because I feel like the stuff Amalia is talking about for example, you could have probably talked about in the seventies or whatever, it's just the methods of distribution have changed. But I don't know if it was the case. Like I feel like a lot of these things have been fairly historically consistent.

AM: Yeah, in that sense, I think this performance is very related to an essay, one of the first essays I wrote, which was about these internet social works in Latin America where people would really use selfies to determine their class. The background of the selfies would mean a lot. Like if you were in the slums, it would be very obvious because the quality of the camera was really bad and you have some shitty bedframe in the background and everything is falling apart. The rich people would be in these normal looking houses. It's just in the background of the picture but it means a lot.

This is one of the things I wanted to play with in the performance: this idea of deception, of how things could be manipulated to that extent, that it becomes real. It was criticized in the media in itself. Not just with female bodies, but in the news: how, by repeating again, again, and again whose the bad one, it becomes an obvious answer.

HB: I just have a bit random, a bit tangential. When you were talking about backgrounds of images, I was thinking about this woman who does "Critique my Dick Pic" who we just ran an essay about in the New Inquiry. She's always like, "Clean your room before you take your dick pic." I don't know if anyone's written about the dick pic and the selfie as these kind of like—because it seems like this totally interesting construction. The selfie, which is mainly young women and they're narcissistic or whatever, and then there's the dick pic where a man kind of signals his erotic capital—

AU: Or happiness—

MC: I think one of the things about your performance that strikes me is that it is very sealed. There's all of these men and people that commented. A lot of them wanted to touch you. It's very much about how there is this disparate nature between what's happening in the social media performance—

AU: One of the interesting things that happened was that even though it's obvious that I am very good at constructing images, even if you don't know it's a performance, they're pretty well done. The amount of messages of guys have been "Can I shoot you?" But taking that power out of me like "Let me represent you," which I found really interesting. That was one of the most interesting things.

MC: There's something interesting about the permeability suggested in your video and the idea of the cyborg image, which is impermeable. Another image that we're seeing now is the impermeable human technological entity, which has been circulating a lot virally in the media. I'm not going to get too specific because I think it's time to see if any of you would like to join in.

AM: Oh sorry, one of the last things that I— with the performance, one of the main things was to point out how femininity is constructed and what's supposedly femininity is this set of symbols, and like, we are not born like that. That was one of the main things, like how it can be manipulated and constructed.

MC: Yeah, I think one of the anxieties I mentioned was specifically around plastic surgery, and it's funny like your performance really situates that in a continuum of ways in which both the body and the feminine identity are as much fiction as social reality. "Social fiction as social reality" to use the Haraway phrase. I would really like to see if anyone from the floor would like to join in.

Audience: I guess I just wanted to ask, how far does it go, the performance. I'm thinking about how I would feel to post something on Facebook and I'm alone and in my room, I'm feeling shit and I want to post something. I'll post it, and it'll get likes. That kind of online-ego will collapse into my real life-ego and I'll feel better at that moment by myself. I was wondering, obviously this discussion is about this performance, but do you ever find yourself falling into the pulls of that?

AM: Actually not, for good actually. I was 100% performing, so it wasn't me. I didn't find myself beautiful in those images. I knew the likes were not for me but for this constructed thing. Especially because, to avoid doing that, I would devote maybe three days of my week to do these: go to a hotel, take all of the pictures, and forget about it and go back to my routine. I would have a folder, and I would upload these things every day to make it more impersonal. For the second episode, which was the one where I got more bullied for, the most extreme one or whatever, I generated all the content for a month in one week, and then the rest of the time I was actually in a meditation retreat in the forest with very limited internet access. While on the internet there was this crazy bitch whoring about Los Angeles and New York, I was actually cleaning cabins and cooking vegan meals. That helped me separate it more and see it more as a project, and it didn't really affect me in that way, at all.

MC: We have time for a couple more. I wanted to ask you— Oh there's a question. It's difficult to see.

Audience: So you're talking about criticisms of society against body as commodity or slave, but you are not talking about the empowerment of occupying your body.

MC: It's a disembodied voice.

HB: It's very scary.

MC: Can you raise your hand? There you are.

AM: Sorry.

MC: So what about the empowerment of occupying your body. This is kind of a Hannah question, can we reclaim embodied experience? I think you were getting into that.

HB: I find this a really, or this is one of my favorite stupid obversations. This strange idea that embodiment is like definitely good, like "occupying your body," I don't really know what you mean by that, but I guess you mean some sort of "I am my body" Kind of thing, which I think can be really great. There are obviously really good experiences of that like eating or sexual experiences or whatever, but there's also terrible experiences of having a body; there's being tortured, there's being abused in various ways, and so I don't know.

As much as it can be good and you can work it to your advantage, there's no like… I'm just interested in the idea that your body is quite a complicated site that also makes you vulnerable to lots of different forms of oppression. For example, you wouldn't have to go to work if you weren't occupying your body. Unfortunately, occupying your body is the reason you have to be able to pay your rent and eat and other things that mean you have to do things you hate doing, probably, unless you’re lucky.

DS: I also think this question of being in your body as sort of mantra has arisen and is circulated, like "be present and be in your body" has really interesting significance in what the subject-position is. I think in terms of encountering racism or sexism, often there's a dissociative mechanism that people who have to negotiate these very abusive and strange terrains employ, which is emphatically not about being in your body in that moment. It's in fact about circumventing that idea. I agree; I don’t feel wedded to that idea about being in your body as being uncomplicatedly empowering.

MC: When you were talking about occupying your body as a mantra, I was thinking about the fact that permeability as another kind of mantra that people kind of pull out as something good, I was thinking about that just because it's this image of going into the interior and, well, so much of what we looked at was about the exterior, except for like Janet Jackson, which somehow seemed very much about permeability. So maybe it's a similar thing, like permeability isn't necessarily good because it’s like who are you permeable to; it's not an inherently good thing.

HB: Sorry, I keep doing slight tangents, but it just occurred to me yesterday and I'm pleased with it. A few days ago, I was complaining about the way that some men in my life (I was saying this as some sort of gendered thing, I know it's not always men, women can do it too), but that thing of being very upset and then sort of retreating, then not wanting to talk about it. It's just something that I personally find frustrating. Obviously, everyone's different; I’m not saying all men and women are like that.

I was complaining on twitter like men blah, blah, blah. And my twitter feminist harrodin persona and someone said "But men don’t talk about there feelings because they feel like it makes them vulnerable." I was like "it does make you vulnerable to talk about your feelings." It’s actually kind of awful sometimes. It’s not always fun. It can be compulsive, or it can make you feel shit. So that thing of like vulnerability, this idea of "it's good to be vulnerable." This idea that we offer men the promise of vulnerability. Actually you're probably doing quite well if you can be totally invulnerable in a hard, like a hard bitch, whatever it is you are. There's a reason people do that.

Same Audience Member: I still feel like you're avoiding the subject of occupying your bodies like if you're being beaten, and you are not within yourself being beaten then you are not actually going to respond appropriately to being beaten to change the fact that you are being beaten. You're going to deny it by some abstract othering—

HB: What’s the appropriate response to being beaten?

DS: Yeah I don’t know if its your responsibility…

Still that same Audience Member: If your posting images of yourself as an anorexic girl having some kind of crisis, maybe you're experiencing that, but you said that you weren't working through it yourself. Meanwhile, you were eating vegan food in a cave—

AU: Oh! What? You’re talking to me now I'm sorry.

Yep, that guy again: Isn't that a more empowering thing to be presenting to other people?

AU: I'm not vegan. I was cooking vegan meals for others. All of the material of the performance has been based on personal experience through me and girlfriends that I had. I was an escort myself; I know how it looks to be in that world. I was in Monaco. I've seen the hookers; I know how it looks like. I didn't have to revisit it to know what it is. For the other part, let’s say the kawaii-aesthetics, I was into animé when I was 16, and I have friends who have eating disorders. I know how that works; I’ve been through that. I've also been through the fact that I don’t really have a family, and I know how to pretend to have one very well like posing with a baby. I know how it feels to have that background, so I did experience that before. During the performance, I was actually working on other things, other essays, like my shows and everything, but it is actually based on personal experience.

HB: The question is funny to me because I thought we’d been fairly articulate on the idea that authenticity as a demand to women is kind of fucked-up, and I feel like it’s a bit strange to them to basically make an authenticity-demand. I just would have hoped that would have been at least something you’d reflect on if you feel very strongly, like "Wow, a lot of people don’t want to be told by men how to be authentic."

MC: I think there is a structure in the world that asks you to disassociate from your body in certain ways. Let’s say some conditions of capitalism, like when you’re on your iPhone on the bus, you're not experiencing being on the bus or something.

HB: Shit on the bus! In London, it's not very good on the bus.

DS: We don't have to be in every single moment. I do find that demand quite tyrannical in an oppressive way.

MC: I think the specific ways in which we are not on the bus are ways that can be—

AU: I love the bus. I’m a weirdo, so..

MC: You can sort of be like monitored and become part of the enormous social experiment that we are all a part of on the internet. Also, in London, I really enjoy the bus; in New York, it's not quite as nice, but it's like public transportation is a really important way in which different social classes can come in contact with each other in the city. I think that maybe some people use the internet in really expansive ways and come into contact with a wide variety of people and have productive exchanges between people who are more or less peers.

Rosalie: Michael we have another question, right here.

MC: We have another question? From the same person, though?

Rosalie: A different person. A woman this time.

Audience Member 3: I guess my question is a bit general. Sort of to get away from the whole feminist discussion, female bodies, male bodies, that distinction. Can you, apart from Amalia because with your project I guess it’s obvious, but how does the whole theme of this panel, the digital, affect the perception of your own body? I don’t think that was discussed enough. So how does the fact that with this digital revolution or the acceleration or whatever we’re experiencing now, whatever the terminology for it is, the present internet, with digital and social media, how does this change or affect your view of the body or as woman or as the gender/race?

MC: The specific theme is internet circulation, and I think the point was made well by Hannah that internet circulation is just the latest form of previous forms of circulation, but I would say there is a difference in scale.

HB: That’s a really contentious point, I know. I thought it would be an interesting thing with what you put out there with the prompt. I wasn't sure who you were asking.

Audience Member: Just generally. Apart from just accelerating it, was there any other change you see or in your work?

HB: Personally, because I’m quite ADHD, and I also have no sense of direction, so in lots of ways, the internet and also having a smartphone— I can't believe iPhones have only existed since 2007. I feel like, in lots of ways, it's been quite life-changing. Also, I use twitter in a very embarrassing way: basically to self-soothe because I get very anxious and sometimes can’t sleep very well, so I'll go on twitter. Especially, most often, I'll be on my own, like in those moments, I'll be very anxious and I'll go on twitter, and I'll say things. People favorite it, and it's a little whatever dog-treat reward. Maybe sometimes people say nice things to you or whatever. It's a bit embarrassing because sometimes people follow me on twitter, it's like "oh god, you have access to my worst moments." So, whatever, I'm just compulsively putting it on there.

[character limit reached]