This text (original title: "The Outskirts of the Internet") was originally commissioned for the book Turning Inward, with contributions by John Beeson, Svetlana Boym, Marta Dziewańska, Philipp Ekardt, Felix Ensslin, David Joselit, William Kherbek, John Miller, Reza Negarestani, Matteo Pasquinelli, and Dieter Roelstraete. Edited by Lou Cantor and Clemens Jahn. Published by Sternberg Press, 2015. The text was modified slightly, including the deletion of a section about Rhizome's own activities. Orit Gat is a Contributing Editor at Rhizome.

![]()

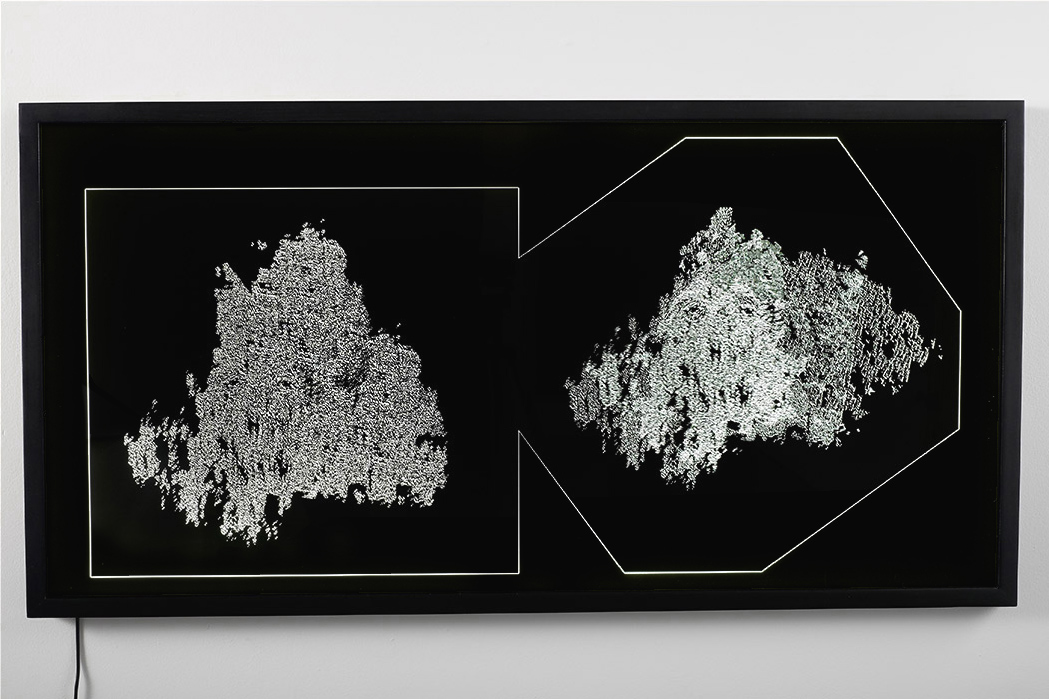

Jim Campbell, Library. GIF excerpt from documentation video.

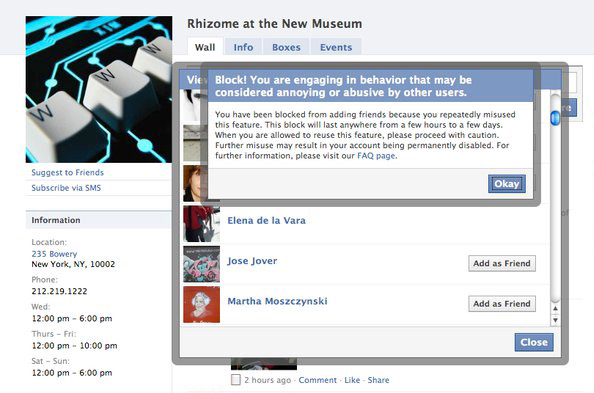

Fifty percent of arts organizations in the United States maintain a blog.[1] The Metropolitan Museum of Art calculated that while the museum draws six million visitors in a year, its website attracts 29 million users and its Facebook page reaches 92 million.[2] Of these millions of people interacting with the museum online, only a small percentage would ever walk up the New York museum's famous steps. If the internet has changed the definition of what a museum's audience is, then it also poses the difficult question of how to interact with it. This adds a new dimension to the museum's relationship with its traditional audience: How to extend the relationship with visitors beyond the museum's walls? This twofold task—both to generate a public and sustain existing relationships—has created a new landscape of digital engagement where museums look to their websites, dedicated apps, and online magazines as tools to involve this new online public.

As museums are rethinking their relationship to their audience online, an increasing number chooses to publish online magazines, and many of these publications emerge from institutions that are not necessarily the major museums in art world hubs. The attitudes toward these publishing initiatives vary—some choose to outline the scope of their publishing platforms in the shape of their programming, while others produce magazines that are thematically related to subjects the museum covers but are not directly linked to the art on view. What they all share is a feeling that online publishing expands the museum's audience, making it a potentially global one. The idea that a museum's public is to be found beyond visitorship is full of potential, but publishing online does not automatically overcome geography and create new relationships with international audiences. On the contrary, these institutions are working to generate content in an environment that is arguably already saturated. Digital presence does not automatically make for global reach, and much of the writing produced online by museums is bound to disappear in the vast amount of content on the internet. YouTube famously has more videos on it than anyone could ever watch—in fact, with 100 hours of video uploaded to YouTube every minute, it would take over a thousand years to view the total running time of videos posted on the platform—this, in less than ten years of existence.[3]Alexa—the Amazon-owned service that gives public estimates of website metrics—makes online publishing seem almost futile. According to Alexa's data, the most visited website in the world is, of course, Google, and an average user spends nineteen minutes and nine seconds a day on it. Facebook averages 27:34 minutes and the New York Times 3:57. Visitors spend almost twenty minutes a day on YouTube and less than three on the New Yorker's site. When so much content is offered, and so little of it seems to attract readers, the goal of museums joining the online publishing game should not be to reach the largest audience, but rather, to create platforms that expand research and the production of knowledge that builds on the museum's mission statement and expands it, regardless of how many hits it generates—a difficult leap to make, especially in terms of the way museums represent their activity and receive funding.

For museums to become significant publishers online, they need to accept that playing the metrics game will mostly only preserve the status of certain institutions: those with name recognition and large encyclopedic collections that can be digitized and utilized in diverse ways, from research to a Tumblr, appealing to an audience that varies from the art historian to the occasional user based thousands of miles away from the museum. This strategy has been incredibly successful for museums that already top the list of visitor counts—the likes of the Met, MoMA, or the Tate and their millions of Twitter followers and Facebook fans. This is not a digital strategy that would work for a contemporary art space in a mid-size city. In the past decade, as institutions internalized the importance of digitizing, a number of attitudes toward online presence emerged. The building of online publishing platforms relates to a traditional role of museums—to support research, then publish and publicize it—and indeed, many museums large and small publish catalogues, books, and sometimes also magazines. But publishing on the internet differs from these initiatives because of the pressure to attract a global audience. If most text online goes unread, how to explain the incentive of these institutions to publish?

What follows is by no means an exhaustive list of museums that publish, nor is it an analysis of each magazine's efforts. The examples used here all originate in US museums (for need of a set case study, and because even though my interest is in whether or not the internet can cancel out geographical limitations, it has also served to uphold a dominance of the English language) and are employed toward a larger point—that in the race to digitize, museums' strategy should not be to publish and send texts out to the world in the hope that they would resonate in the internet void, but rather to consider publishing as an opportunity to expand the intellectual sphere in which they work, rather than their audience.

![]()

Thomas Struth, Audience 1 (Florence, 2004).

Where we are now

Museums' online magazines fall pretty comfortably into two categories: those that serve to perpetuate and develop the institution's mission and those magazines that have their own separate identity and set of interests, which serve in turn to complement those of the institution that funds them and gives them its brand.

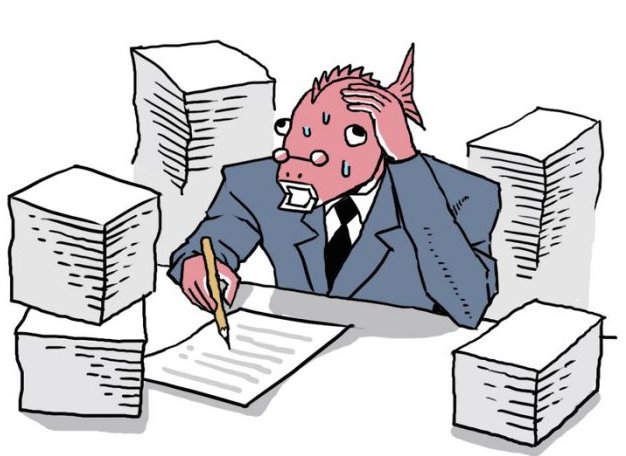

Of the magazines that share a mission with the institution that publishes them, there are two tendencies: the first is to extend the institution's intellectual reach, commissioning original pieces that either react to the institution's programming or somehow build on it. The second is a certain propensity toward behind-the-scenes-like reporting, varying from blogs like the ICA Philadelphia's blog Miranda to the Minneapolis Institute of Arts' Verso, an award-winning iPad magazine. Miranda, which ceased publishing after five years of regular articles about everything that happened in the ICA's curatorial offices, from planting in the museum's garden to interviews with artists and the planning stages of exhibitions, is supposed to resume in a different format following a redesign of ICA's website. Verso runs five to ten pieces in each issue of the quarterly publication, all pertaining to the institution's exhibitions and public programs and to its local community. The Los Angeles County Museum of Arts (LACMA) publishes Unframed, which is written in full by the museum's staff: each contributor writes about their role in the institution and about artworks, events, and other aspects of the museum's activities with which they engage. Thus, the museum's director of artist initiatives recently reflected on the moving of Michael Heizer's sculpture Levitated Mass (2012)—that 340-ton boulder that sits atop a concrete trench—to its current home at the entrance of the museum as an introduction to the screening of a documentary which was shot during the ten-day move of the work from a quarry some 100 miles east of Los Angeles. Another institution that uses publishing as a way of giving its staff a stage on which to communicate with the public is MoMA, which in 2013 introduced Post, a journal-archive hybrid as part of its C-MAP research initiative, that brings together practitioners from across the modern and contemporary art world to think through questions of value, quality, geography, and history in art practices, especially ones originating in countries that are not in North America and Western Europe. While C-MAP's activities and seminars largely take place behind closed doors, Post is an open platform that allows for user participation (mainly by allowing comments) and is oftentimes used for reflections specifically on C-MAP activities, seminars, and for C-MAP participants to write about their ongoing research. Interestingly, most of the articles on C-MAP have garnered zero discussion (at times there is a single comment written by the author of the article and used to update an argument or bring in new links and information), which means that even though Post was envisioned as an active platform that allows for an expansion of this one part of the museum's activity, it has basically become an archive or a container for the writing that resulted from C-MAP.

The transparency that these institutions try to promote by way of publishing online may not result in articles shared by the thousands, but it produces self-reflexivity and a writing of the museum's history by its own members. That's one example of the value of what may seem a modest ambition, but results in giving the museum's visitors a sense of agency owing to their understanding of the inner workings of the institution. A visitor who reads Miranda or Verso will have an idea of the intellectual work that went into the exhibition they encounter or the presentation of the artwork they see, an understanding that goes beyond what any wall text can provide by giving them both the background of the underlying ideas that led to that project, but also a grasp of the work that went into it. It is one way of creating distinct content on the internet: the Heizer text mentioned above, for example, may come up in research about the artist's large-scale sculptural work, and the contribution LACMA's magazine does is exactly in providing a detailed description of the administrative tasks of exhibiting works like Heizer's. No art history would give a reader that hands-on impression of the work.

![]()

Sree Sreenivasan, the Metropolitan Museum's chief digital officer, at the Charles Engelhard Court in the American Wing. Credit Nicole Bengiveno/The New York Times

On the other side of the ring are institutions whose publishing arms are conceived as extensions of the organization, producing new texts that pertain to the institution's mission but are not necessarily married to its activities. One practical way in which these organizations do that is by commissioning outside writers. The Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College launched Red Hook, an online journal that features writing from curators, artists, and other cultural producers about the current state of curatorial and artistic practice, as a way of expanding the institution's approach to curating to allow for slower, more reflexive thinking that isn't just exhibition-making. This attitude means that these two institutions not only produce knowledge about their program, but also create a context for the work that they do. The benefit of this newly-commissioned material is that it furthers work done in these institutions without being directly implicated in their day-to-day operations. And while other outlets—magazines, newspapers, panel discussions—may also generate new research on these topics, here it is nestled under the rubric of these museums' websites, providing a set of new ideas that inform the workings of the institution, as well as the visitors to its site. It frames these institutions as a nexus of meaning, which is fostered in publishing as well as in programming, but online it is more visible by way of texts, which are searchable, and thus position the museum's website as part of a network of research results pertaining to its mission and interests.

When the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis introduced its new website in 2011, in which the homepage is dedicated to a publication, it met with sweeping approval. The Walker Magazine's scope runs the gamut of publishing about the museum's exhibition program, artists in its collection, and other institutional developments, but it also issues longform essays that go beyond the museum's particular program, including, for example, artist op-eds: a series of commissioned opinion pieces that "examine the thinking of artists as citizens and change-makers." It also features essays "from elsewhere," that is, prominently displays essays from other publications about subjects that the Walker's editorial staff deem important or pertinent to discussions that take place in the Walker's magazine and between the museum's walls. Linking from the museum's website—to newspapers, art magazines, YouTube, and other places online—is a brave decision, as it means the Walker may lose readers in favor of the sites to which it directs them, but it makes the Walker Magazine a source that centralizes reading lists about ideas that are central to the museum's mission, making its site both a resource and a "hub for ideas," as the museum's director, Olga Viso, introduces it.[4]

The Walker's site was called a "game changer" by a number of bloggers precisely because of the system it created, in which the magazine serves both the museum's local audience and the larger online public. Furthermore, by publishing this variety of content and not privileging the local over the global (or the other way around) it brings the two closer together.

How the internet is different

Looking under the hood, few of these museums have created online publications that truly advance technology in any practical way. None of them created new features for collecting articles, annotating them, or participating in their making, for example, all of which are technologically viable (though rarely promoted). Considering that this is an industry that trades on the creativity of its members, and that many museums directed substantial budgets towards the creation of these magazines, it is a squandered opportunity for the publishing community to consider these newly-foundedpublications as opportunities to research needs in online publishing and develop new technologies that may advance online publishing as a whole. What these publications did do, however, is shape their readers' attitudes towards—and expectations of—online publishing in the arts. The team that developed Verso wrote a long reflection about it in Beyond the Printed Page: Museum Digital Publishing Bliki (a bliki, according to Beyond the Printed Page, is a combination of a blog and a wiki. Moderated by staffers of the Art Institute of Chicago and edited by a committee from a number of US museums it runs posts by museum publishers, editors, and designers about digital strategy, copyright, functionality, and examples for digital publishing in the museum context) explaining that their goal was not to take a print publication and turn it into a PDF with some hyperlinks. Instead, they designed it to be interactive, so that every story has video and audio features or high-resolution images. These features provide one good reason to make the leap from reading print publication to digital ones and Verso provides a great example of the irreplaceable benefits of e-publishing. The impact of which is already visible, for example, in an emblem of museum publishing, which is currently undergoing a conceptual overhaul—the scholarly collections catalogue. A book that describes the museum's holdings, including physical condition report, provenance and exhibition history, and research about each piece in a museum's collection, the collections catalogue essentially becomes dated the second it is printed. Works are acquired and deaccessioned, others are restored or loaned out—and all these details need to be constantly updated in a book that is oftentimes already a tome of sizable proportions. In 2013, the Getty Foundation set up OSCI, the Online Scholarly Catalogue Initiative, introducing digital publishing as a natural solution to the need for—and problematic nature of—the collections catalogue. In the Getty's online magazine, Iris, Anne Helmreich, the senior program officer at the Getty, explains what makes the collections catalogue such a strong candidate to make the shift to digital publishing: "Because almost all museums produce them, yet they have serious limitations. Catalogues become quickly outdated any time a new work is acquired or new research is discovered, and the space constraints of print often limit how much information a curator or conservator can include."[5] OSCI has produced numerous catalogues for institutions like the Seattle Art Museum, LACMA, and the Walker Art Center. The latter published a piece on its journal about the creation of its Living Collections Catalogue, which allows the museum to continually update their holdings, but also to present parts of its collections, such as performance art commissions and internet artworks, which would traditionally not be published in a book, at least not to a full effect.[6] This layered approach to the possibilities of digital publishing is exactly the contribution that museums can make to the constantly growing field of online publishing.

![]()

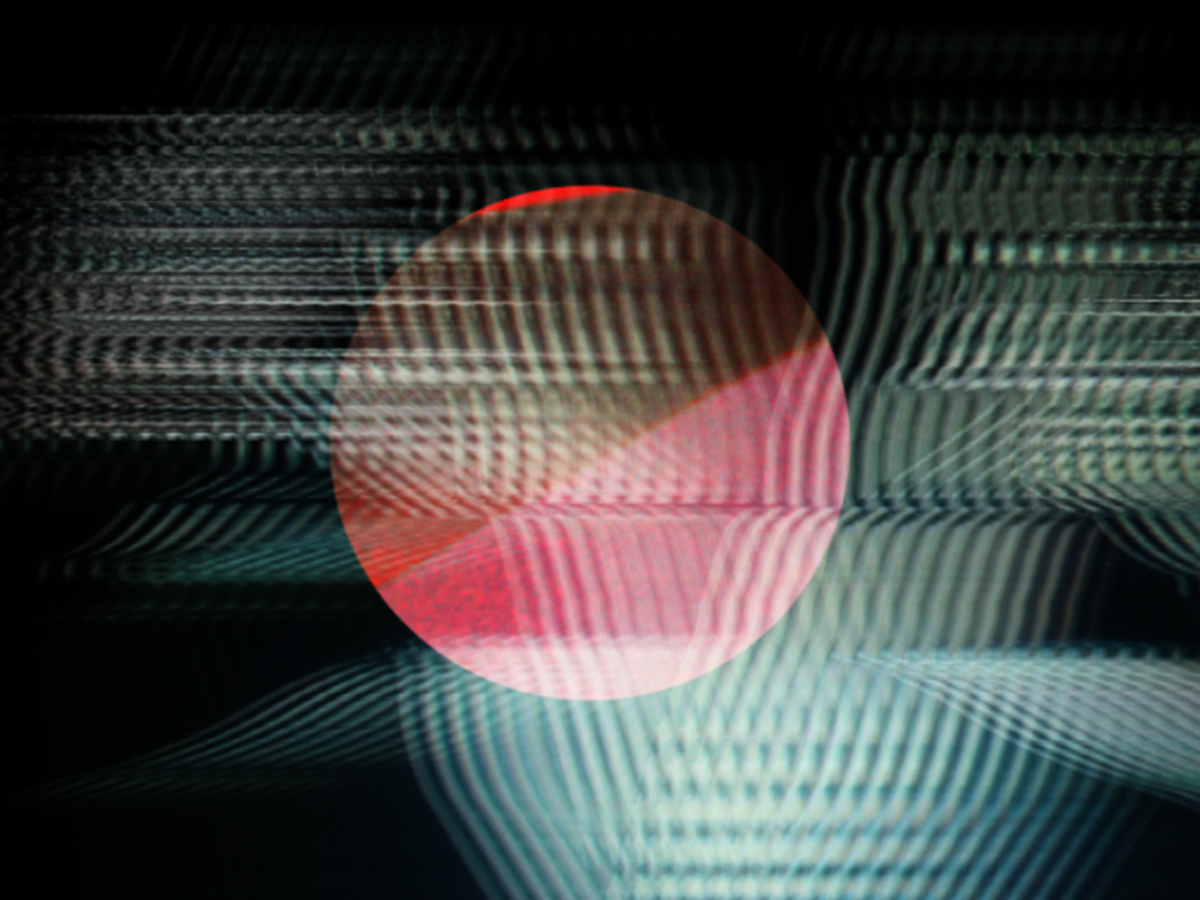

Verso promotional image

Beyond technology, zoom-able images and video content are not the only things setting museums' online publications apart. What distinguishes these online magazines from other museums' print magazines—like the Tate's Tate Etc. or the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, which publishes Palais—is its relationship to its readers. In a post on the digital publishing bliki, Kris Thayer and Diane Richard, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts staffers who conceived and developed Verso (their title is Audience Engagement Strategist, while Thayer is a designer and Richard is a writer; Richard also edits Verso) shared their workflow charts comparing print magazines to their digital endeavor. While the traditional workflow chart ends when the magazine is ready—articles are edited, then sent to proofreading and design, issue laid out, issue reviewed by museum leadership, files released to printer, and delivery as last step—their digital publishing workflow chart includes similar steps but ends with "publish, share" as ways to push out content, leading to the final step: "Next: conversation."[7]

Encouraging conversations aligns all too perfectly with the mission of museums to educate, make knowledge available, and promote new research. But setting sights on communication online often results in audience anxiety. Unlike the activity of a museum's Facebook profile, Tumblr, or Twitter feed, which are all measurable, how does one measure the success of these museums' magazines? Metrics give much information about numbers of visitors and the amount of time they spend on the site, but the impact of these publishing initiatives will be measured in conversations—in academic citations, of course, but mainly in the way articles from these online magazines circulate online via social media and in the overall awareness of a given magazine. This is where things get difficult. The Walker Magazine, for example, has its own Twitter feed with 1100 followers (as of September 2014), while the Walker Art Center has 437,000. Still, running the URL of an artist op-ed by James Bridle published in July 2014 into Twitter's search gives results from September, meaning that the text is still generating discussions months after it was published. This is one successful example of the location where conversations happen. And, even if it allows the museum less control over it, dialogue rarely happens directly on the magazines' sites. While most of them allow for comments, few have a dedicated audience who reads and comments thoughtfully on the articles on the site. Even when there are comments—because oftentimes comments sections remain unused—they are rarely useful, generative discussions that engage a number of readers; usually they are one person reacting to the text (in the best case scenario) or complaining about unrelated topics. Comments sections are infamously full of negative feedback written anonymously, and yet, so far, they're the best we've come up with in terms of audience engagement online.[8] Saying that publishing online rather than in print allows for reader participation is buying into internet optimism—the creation of a space is not enough to make it useful.

The most substantial conversation these online publications create is in commissioning original content. Publishing a magazine may be a less visible activity in terms of metrics than running a blog, Tumblr, or Twitter feed, but it could expand our understanding of both fields—art publishing and museum work. A museum's online publication does not need to publish some of the tropes of mainstream art publishing, such as reviews or previews of gallery shows, which are crucial in the sphere of writing about art but are also inextricably tied to magazines' advertising revenue. This makes them more flexible, since these magazines do not necessarily have columns and features that need to be filled on a monthly, weekly, or daily basis. There's also the question of length: while magazines and books give writers strict word counts, an online publication could run pieces as long as it wishes—and longform essays tend to circulate better on the internet (via sites like longreads.com, which gather and share links to longer pieces published online, and thanks to read-it-later services like Pocket and Instapaper, which allow users to save articles to their mobile devices and access them online), performing in a way that is independent of the site in which it was published, but still sends users back to it.

![]()

Screengrab from the LACMA website

Circulation, funding, and name recognition

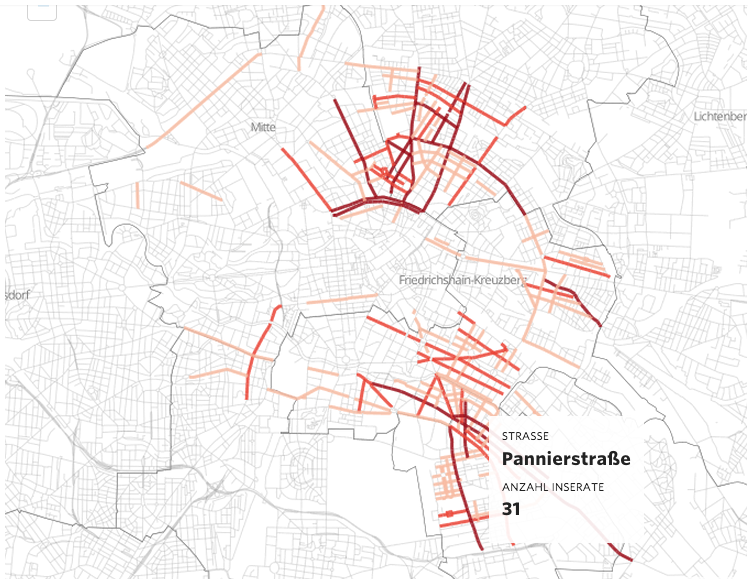

Awareness is a hard ticket to run on in the internet sphere. What if all this original content that museums produce disappears online? The digitizing frenzy among museums (largely supported by grants from the likes of the Getty and Mellon foundations) is shaping the way digital information—and especially images—is circulated. The Met recently made a trove of high-quality images of works in its collection available free of copyright. A decision like that plays into the discussions around "openness" on the internet, where talk of public spiritedness and democracy mask the monetizing structures that lie underneath the surface of these supposed gift economies.[9] The Met making these images available is a move toward free circulation of digital content, but it will also result in many universities, publishers, and others using images from the Met's collection exactly because they are freely available, perpetuating the museum's hegemony in art historical discourse. The result is that an institution like the Met, already one of the most visible museums in the world, now considers its audience as much larger than the people walking through its galleries, which in turn leads the museum's online strategy. In September 2014, the Met launched its official app. In the media frenzy that followed the launch, Bloomberg Philanthropies (which financially supported the app) released a statement from the museum's director, Thomas P. Campbell, that "you must digitize in order to survive, and Bloomberg Philanthropies is helping us do that."[10] The Met app includes some obvious features—information about current and upcoming exhibitions, events at the museum, membership information—as well as some less-obvious ones (especially the "Met-Staches," a wink at viral content in the form of a "sample of the Met's choicest moustaches, from stately to scruffy," that is, a series of images of men with mustaches from the museum's collection), and some impressive omissions (there is no map of the museum's galleries). Digital survival according to the Met means to provide a superficial connection with a public: the app does not create knowledge, only collects and presents it in an easy-to-digest version that is also easy to share and circulate. Like the image program, it is there to sustain the Met's stature.

With the launch of the Met's app, the New York Times ran an article in its arts section surveying two New York museums' relationship to their online audience. Entitled "Museums See Different Virtues in Different Worlds," it discusses the "anyone, anywhere dream," as the Brooklyn Museum's vice director of digital engagement and technology Shelley Bernstein called it, relating to the idea that just by virtue of being online the content the museum produces is global and could appeal to audiences anywhere.[11] Under Bernstein, the Brooklyn Museum experimented for a number of years with crowd-sourced exhibitions ("Click!" in 2008) and games ("Tag! You're In It," also 2008, which encouraged users to tag works in the museum's collection, as a way both to enhance their sense of authorship and use the "wisdom of crowds" in order to update the site). What the Brooklyn Museum learned from these experiences was exactly the opposite from what the Met did—that even if on the internet their activities can spread across the world, the majority of their audience was still local—in Brooklyn—and in response, the museum reshaped its digital activities to suit its immediate public. In the Times article, Bernstein says that the lesson she took away from focusing on the museum's visitors is that an institution should "not let the tech community drive what you're doing because it may not be right. Digital is not the Holy Grail, it's a layer."

Being active online does not immediately make an institution global. And focusing on expansion only perpetuates some wrong tendencies related to the internet and its supposed promise of infinite possibilities. There is a very Silicon Valley-like attitude in focusing on numbers (what makes Facebook's valuation is not anything the social network produces, but the sheer quantity of its users) rather than content. The fact that the internet allows institutions to build platforms does not mean that their end goal is accumulation—rather, it is in a commitment to sustaining research and building knowledge. This is why the Walker is such a groundbreaking example. While the Minneapolis art center is surely a recognizable, revered institution, it is not as globally recognized as the Met is. And yet, it has created a structure that doesn't only allow it to participate in conversations that go beyond its immediate community, it also makes it a useful resource, thus expanding its reach by way of content, not of subscribers. We need to think about online publishing in terms of discourse, debate, and exchange—and the foundation for these dynamics is in commissioning texts that help produce a broad context for institutional activities.

![]()

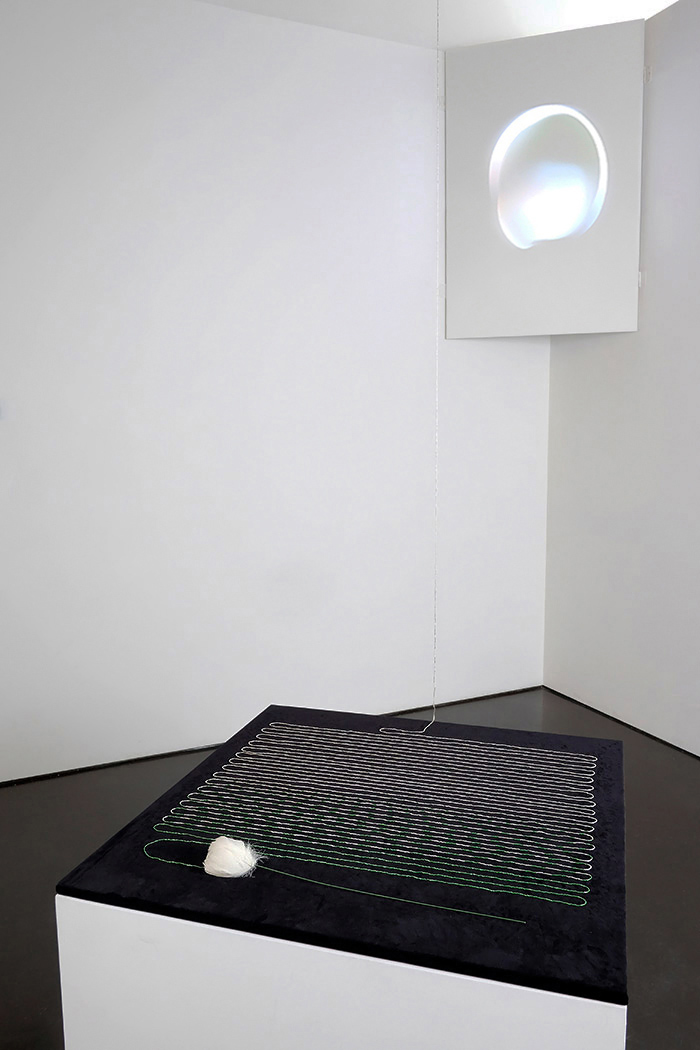

Image from the Walker Art Center's first edition of the Living Collections Catalogue

A last thought on numbers

Maria Hlavajova, the director of BAK (Basis for Aktuell Kunst) in Utrecht, in the Netherlands, has publicly discussed her idea of the institution's "zero visitors policy": zero visitors, Hlavajova argues, does not mean zero public, but suggests that an art institution's reach goes beyond its walls. Counting the number of people who walk through the doors of BAK is irrelevant to the type of engagement the institution fosters with its audience, be it via public programming, publishing, or relationships formed with other cultural practitioners. In the context of the budget cuts for cultural institutions in the Netherlands, BAK is a prominent example of a space that considers its public to be as varied as its activities, both of which reach far beyond the bricks and mortar museum. This should be an example for the way museums consider their activities online: to conceive of the internet not as a tool to cancel the geographical constraints of what is considered to be a museum's traditional audience, but as a space in which a museum can participate in larger conversations that relate to its mission.

In the same Pew Research Center cited in the opening of this essay, 65 percent of the cultural institutions surveyed stated that digital technologies are very important for fundraising. One of the goals of development departments in places like the Walker Art Center and the Brooklyn Museum should be to delineate new ways in which digital engagement encourages public involvement, which should not be measured via circulation, but by way of their impact on the museum's ongoing activities. An article published on a museum's online publication could provide the background for a conversation in the galleries; choice paragraphs from an artist profile preceding an exhibition could be used for wall labels; different series of readers or anthologies based on the online publication could be compiled to thematically relate to the museum's program as a way of both expanding the resources available to the public when visiting the space and tying together the publishing arm with the programming. These are all examples of aspects of publishing that funders should look to support. The worrying tendency of museums to crowdfund via sites like Kickstarter exemplifies yet another stressing of quantity versus quality. While fundraising strategies change from one local context to another, in their funding applications, be they for a national agency or a philanthropic organization, nonprofit institutions need to sidestep the numbers question as pertains to the internet, because metrics do not mean what donors seem to think they mean. We should change the way we fund institutions, think about them, relate to them. Online publishing could promote not only new writing and research, but also new ideas as to what a museum's role can be, which will not be achieved by winking at a broader audience, but by doing the work, every day: hiring editorial staff, reading what else is published online, reacting to the current intellectual situation. In eschewing print in favor of the larger context of the internet, museums gain both the possibility of a significant audience and the option to be timely, to become a voice in conversations that happen beyond their walls. But these dynamics need to reflect the potential of online publishing platforms: to provide an expanded context for institutional activities (on the scale and in the terms of the originating institutions), rather than be conceived of as expressways into the digital realm. What the internet allows is not a reshuffling of geography—since simply being online does not make an institution global. Instead, it is a new landscape in which to participate.

Notes

[9] For more on the language of openness, see Astra Taylor's excellent The People's Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2014), 20–25.

Ann Hirsch, Playground, 2013 Performance at the New Museum

Ann Hirsch, Playground, 2013 Performance at the New Museum