![]()

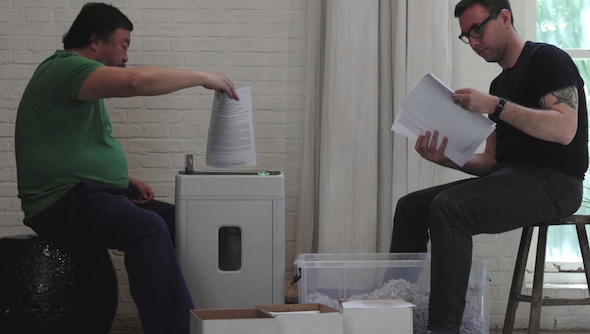

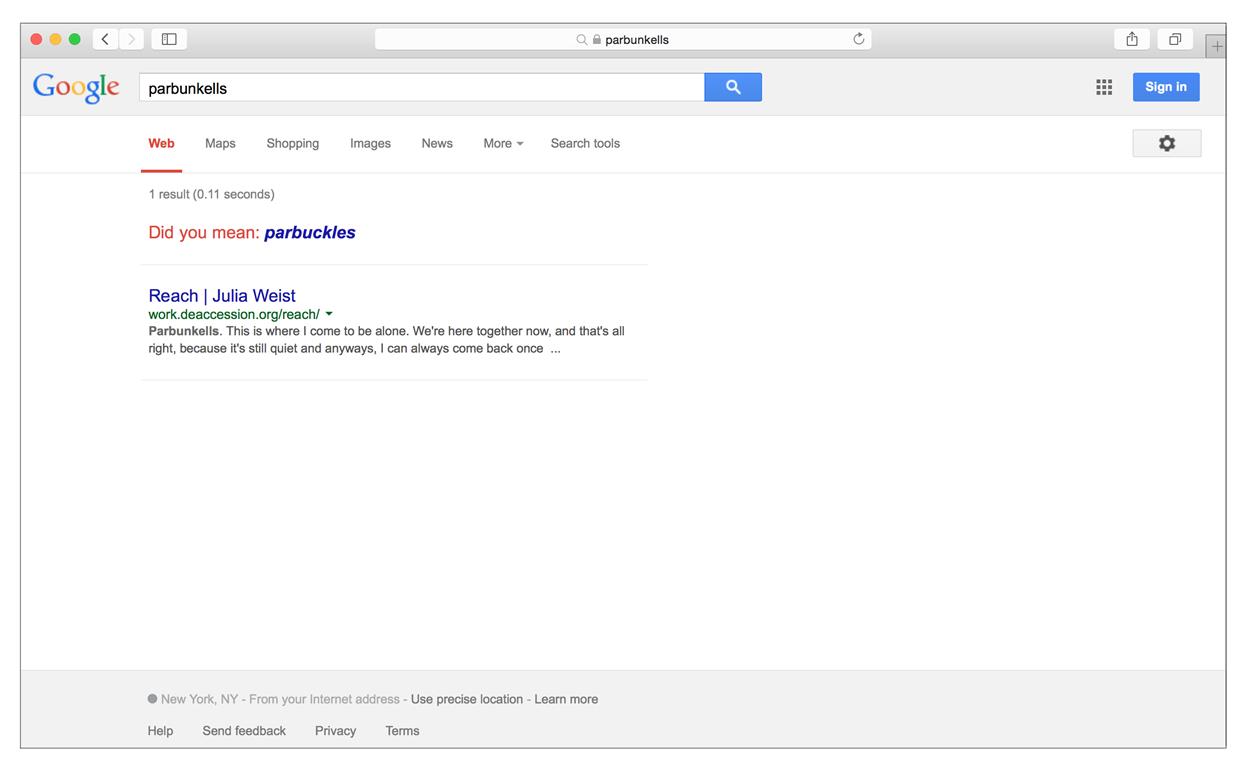

Allan Sekula, Gas Terminal, Barcelona (2008) from the series "Methane for all."

When an American crew picked up the first of these ships from the Daewoo dockyard, completed the sea trials, and began the voyage back across the Pacific, they discovered in the nooks and crannies of the new ship a curious inventory of discarded tools used in the building of the vessel: crude hammers made by welding a heavy bolt onto the end of a length of pipe, wrenches cut roughly by torch from scraps of deck plate. Awed by this evidence of an improvisatory iron-age approach to ship building, which corresponded to their earlier impression of the often-lethal brutality of Korean industrial methods, they gathered the tools into a small display in the crew's lounge, christening it "The Korean Workers' Museum."

- Excerpt from Allan Sekula's Fish Story (1989-95)

If we lift up the manhole cover, lock-out the equipment, unscrew the housing, and break the word into components, infrastructure means, simply, below-structure. Like infrared, the below-red energy just outside of the reddish portion of the visible light section of the electromagnetic spectrum. Humans are not equipped to see infrared with our evolved eyes, but we sometimes feel it as radiated heat.

Infrastructure is drastically important to our way of life, and largely kept out of sight. It is the underground, the conduited, the containerized, the concreted, the shielded, the buried, the built up, the broadcast, the palletized, the addressed, the routed. It is the underneath, the chassis, the network, the hidden system, the combine, the conspiracy. There is something of a paranoiac, occult quality to it. James Tilly Matthews, one of the first documented cases of what we now call schizophrenia, spoke of a thematic style of hallucination described by many suffering from the condition, always rewritten in the technological language of the era. In Matthews' 18th Century description, there existed an invisible "air loom," an influencing machine harnessing rays, magnets, and gases, run by a secret cabal, able to control people for nefarious motives. Infrastructure's power, combined with its lack of visibility, is the stuff of our society's physical unconscious.

Perhaps because infrastructure wields great power and lacks visibility, it is of particular concern to artists and writers who bring the mysterious influencing machines into public discourse through their travels and research.

These contemporary ethnographers are more likely to be found in hard hats than pith helmets. Charmaine Chua, who rode on a container vessel for thirty-six days in order to document the workers of the shipping supply chain, calls herself an ethnographer, though she herself is hesitant of what that might mean:

Ethnography may be an unseemly choice against this dizzying and daunting backdrop of structural transformations. I do not know how much I will find out, how much will make sense, or how much will be useful. I am cautious about being the only woman on the ship; more cautious still about the potentially arrogant, certainly intrusive position of the paying passenger-researcher on board. There are some things I do know: Seafaring work is an endeavor practically invisible to all of us who benefit from the toil of sailors, and remains one of the most contingent, yet internationally diverse forms of labor. The embodied experience of traveling across the ocean is a journey few have taken in the decades since air travel. We know that capital fantasizes about the annihilation of space and time as its moves goods from space to space, but I want to experience the long, slow journey that is responsible for moving ninety percent of the world's trade. In ways that may never make it to a page, I imagine that this feeling of being afloat, suspended between continents, trying to understand value in motion from one of its most liminal spaces, will stay with me long after I am done researching.

![]()

Allan Sekula and Noël Burch, The Forgotten Space (2010). Still image from documentary film.

There is a value in seeing first-hand, and this experience is something that is treated as privileged resource, but shared in the spirit of research. Consider Unknown Fields Division, a "nomadic design research studio," run by Kate Davies and Liam Young, "that ventures out on expeditions to the ends of the earth to bear witness to alternative worlds, alien landscapes, industrial ecologies and precarious wilderness." Participants share their experiences with those of us who cannot make the trip, like journalist Tim Maughan, whose dispatches from container ports, Christmas decoration factories, and toxic waste dumps visited on Unknown Fields excursions both horrify and captivate those of us back in the West, who do not have the full picture of where our goods originate. Dan Williams, another participant, wrote a series of dispatches called Postcards from a Supply Chain, but also mused about ways that other tools carried into these below-structures might document the area. "I carried a GPS logger, a software defined radio dongle for recording AIS signals, a GoPro and a camera with me. I'm particularly looking at how a software developer might explore supply chains, as opposed to a writer or photographer or filmmaker or artist."

While first-person accounts offer glimpses of the human experience of infrastructure, maps are particularly helpful for conveying a sense of infrastructure's great complexity. For her study of refrigerated food production in the United States for the Center for Land Use Interpretation, Nicola Twilley prepared an interactive map of over 130 different food preparation, storage, and shipment locations, creating a digital "refrigerated landscape," for those of us to explore, who rarely see food anywhere outside of the short path between the grocery store and our kitchens. Using this technological tool combined with Twilley's extensive research, our awareness spreads wider than a single person ever could see.

Visibility, or lack thereof, is common theme in infrastructural research, spoken of directly in artists' statements, introductory texts, and essays. The language of diagrams, of hidden sites, of the bottoms of icebergs, of ignored vantage points, of proprietary buildings fills the legends of these infrastructural maps and guides. But this is not the fault of the researchers. The infrastructure itself is designed to be kept out of sight, visible only to those with technological access for the purposes of management and security. So why do we go to the effort to make it visible?

Perhaps because of the lengths those in power will go to control the visibility of infrastructure. Emily Horne and Tim Maly's book The Inspection House tracks panopticons, both literal and conceptual, across the world from prisons, to military bases, to ports, to iPhones in our pockets. They note the peculiar fact that while the panopticon prison was first described by Jeremy Bentham, it was inspired by a factory layout conceived by Jeremy's brother Samuel, a mechanical engineer. Thus the original panopticon or "inspection house" was meant to watch not prisoners but workers, solving the problem of supervisory-enforced efficiency among skilled laborers. This surveillance task must be as old as capitalism itself, extending not just between the boss' eye and the employee's hand, but to the entire infrastructure of the body. Consider, for example, the "bathroom break," a fundamental right now guaranteed by US labor law (but only as recently as 1998) insomuch as it is defined exactly when, how, and for how long a human being might service their own internal infrastructure for the sake of their health, while not encroaching too much upon an employer's right to demand the worker remain part of the functional workplace line. In September 2002:

A Jim Beam bourbon distillery in Clermont, Ky., was forced to drop its strict bathroom-break policies after the plant's union focused negative international attention—from ABC News to Australia—on Jim Beam and its parent company, Fortune Brands, Inc. According to union officials, managers kept computer spreadsheets monitoring employee use of the bathroom, and 45 employees were disciplined for heeding nature's call outside company-approved breaks. Female workers were even told to report the beginning of their menstrual cycles to the human resources department, said one union leader.

The employer considers the worker's body to be a part of the factory infrastructure, and it attempts to maintain oversight over even its most hidden functions. Visibility, and the control it allows, defines all work sites, regardless of what is being manufactured or supplied.

It just so happens that Samuel Bentham built his inspection house while under the employ of Prince Potemkin, namesake of the famous "Potemkin Villages." A perhaps-apocryphal story describes a counterfeit model village orchestrated by the prince, moved to different areas of the countryside at night, for the purpose of keeping up appearances for the visiting czar. Bentham watched his workers, out of worry for his factory's appearance to his boss, just as the prince was said to be worried about the observing eye of Catherine the Great. Vision is power, and infrastructure is built for and by a world that believes in this philosophy: its image is carefully controlled and constructed, and the capacity for watching and being watched becomes its own infrastructure.

Our culture loves a good Copernican irony to describe balances of power, but the most important infrastructure research reveals that the below-structure is more than what can be seen or not-seen, known and not-known. Infrastructure is not built on an architect's map or in front of a CCTV monitor, but by the service laborer out in the truck, untangling the wires. And it is further modified by the fishermen, stealing fiber optics cables. The only people who think they are maintaining control with information alone are spies who build homages to science-fiction war rooms while the real work is done in the depths of a server somewhere, closer to cheap electricity. Spies build structures of information via dossiers, theories, databases, and plots, while workers build the infrastructure that is a mechanism.

Photographer Allan Sekula, in his book Fish Story, assaults our intellectual reliance upon an equivalence between information and infrastructure:

In effect, I am arguing for the continued importance of maritime space in order to counter the exaggerated importance attached to that largely metaphysical construct, "cyberspace," and the corollary myth of "instantaneous" contact between distance spaces. I am often struck by the ignorance of intellectuals in this respect: the self-congratulating conceptual aggrandizement of "information" frequently is accompanied by peculiar erroneous beliefs: among these is the widely held quasi-anthropomorphic notion that most of the world's cargo travels as people do, by air. This is an instance of the blinkered narcissism of the information specialist: a "materialism" that goes no farther than "the body."

For Sekula this intellectual body is singular, first-person, fooled by its powerful informatic telescopes into thinking it can see everything. There is always a danger of myopia in infrastructural work. In the bright light of a revealed world we are dazzled by the mystery of scale, the techno-capitalist sublime, and we might forget the lived realities we are dealing with.

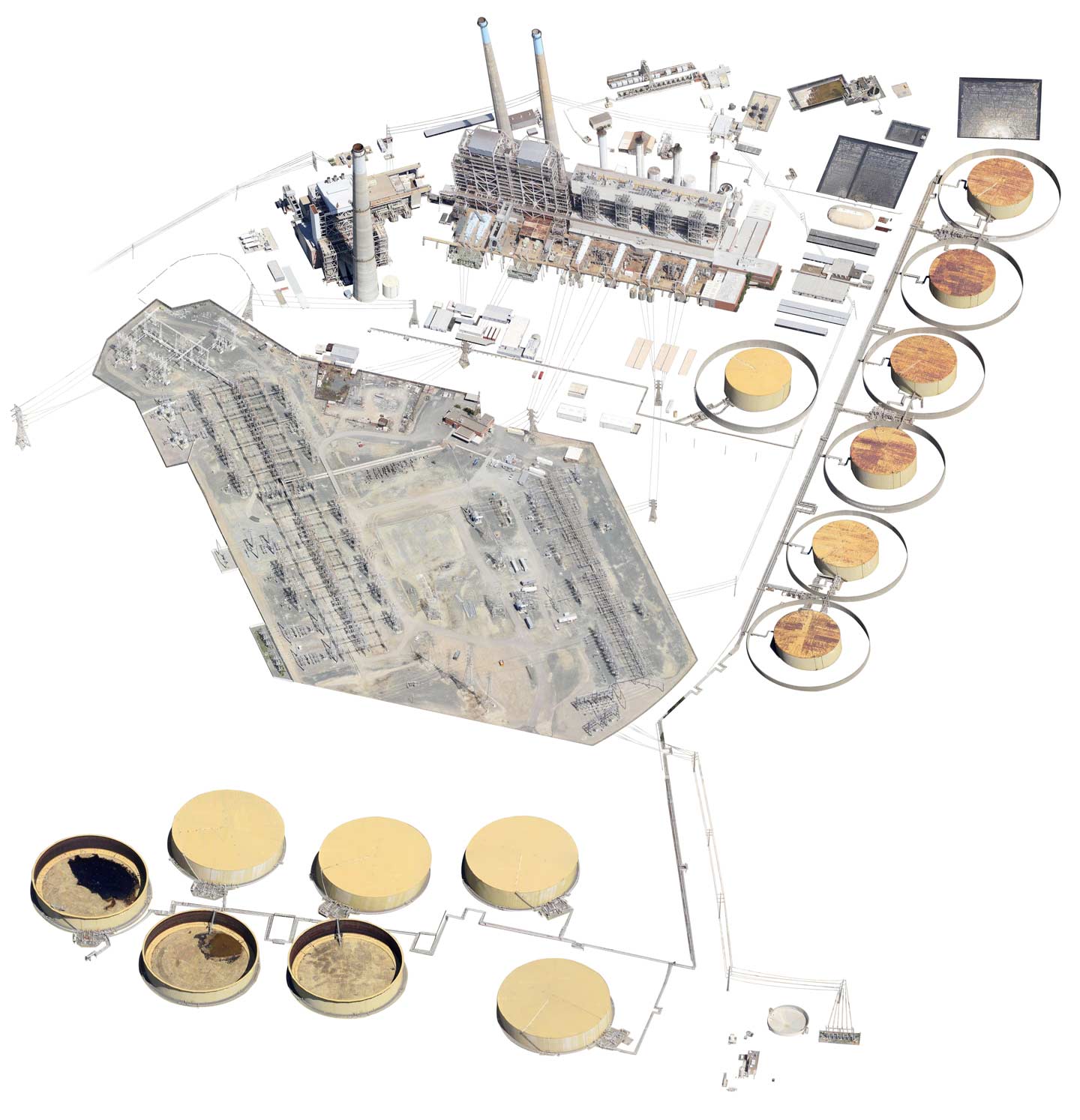

It is tempting to play with speculative utopias, as if infrastructures were mere Lego sets. In Jenny ODell's Satellite Landscapes, the artist plays with the fantasy of a world laid bare as pure information, taking the future-forward images of infrastructure from satellite views, and cutting them free from their landscapes, presents them as blueprints, as living creatures, and space stations placed in a white vacuum. For ODell, the invisibility of infrastructure is displayed in our forgetting of the "stubborn physicality" of these structures. Satellites are a fantastic technology, but they are not the landscape. The catalog of human infrastructures that can be "seen from space" grows with each additional satellite lens. But where are the people? Certainly, there are workers down there somewhere in the satellite imagery. We know that there are. How can we see them? How should we see them?

![]()

Jenny Odell, work from the series "Satellite Landscapes" (2013-2014).

Donna Haraway describes the fantasy of an overhead-vision reality as the "God's Eye View":

Vision in this technological feast becomes unregulated gluttony; all seems not just mythically about the god trick of seeing everything from nowhere, but to have put the myth into ordinary practice. And like the god trick, this eye fucks the world to make techno-monsters.

Haraway suggests not a departure from vision and its fantasies, but a reconstitution of how vision is carried out. She repeatedly refers to the analogy of "primate vision," to remind us exactly where our eyes exist in the ecological infrastructure. Outside of the binary system of the Panopticon and the Potemkin village attempting to fool it, we ought to build a vision that can stand in different places at different times to view multiple bodies, without forgetting what this looking means and how it works, and exactly whom is getting fucked when the techno-monster is born.

She continues: "Feminism is about a critical vision consequent upon a critical positioning in unhomogeneous gendered social space." This isn't simply about a multiplicity to replace singular vantages. It is about understanding the territory as always a space with power avenues coursing below it. It is not about postmodern subjective narratives to replace objective knowledge either, in an attempt to install the cameras in the body, to make the "I" into another eye. It is about trying to decide, for seven-billion-and-counting upright, naked primates, what exactly "I" is supposed to mean. Haraway seeks "situated knowledges." Infrastructural ethnography, symbolic monographs, aesthetic explorations of data—these sorts of knowledges do not attempt to be everything, but never forget what they are and where they got their material. Infrastructural research does not claim to be the last word, and it does not claim ownership over its content. It does not treat our human thirst for resources as a resource, and instead treats it as a labor, deserving of value.

Our studies of infrastructure must do what infrastructure itself has failed to do, creating situated knowledges that teach us what is underneath our society, rather than simply metering information as commodity through more optic tubes. We do not need a snatching away of the shroud, a techno-monster captured and paraded on stage. Not like an animal or person harnessed to a profit-generating machine. Not a big board of big data, constantly tweaked by a wizard's wand. But a description of what the shroud is doing, and why it is there. To discover who it is hiding, why, and how they came to be there. The efforts of researchers and artists to discover what is going on with our infrastructure is not about commanding god-like powers, but about speaking with the spirits, wherever they chose to haunt us.

![]()

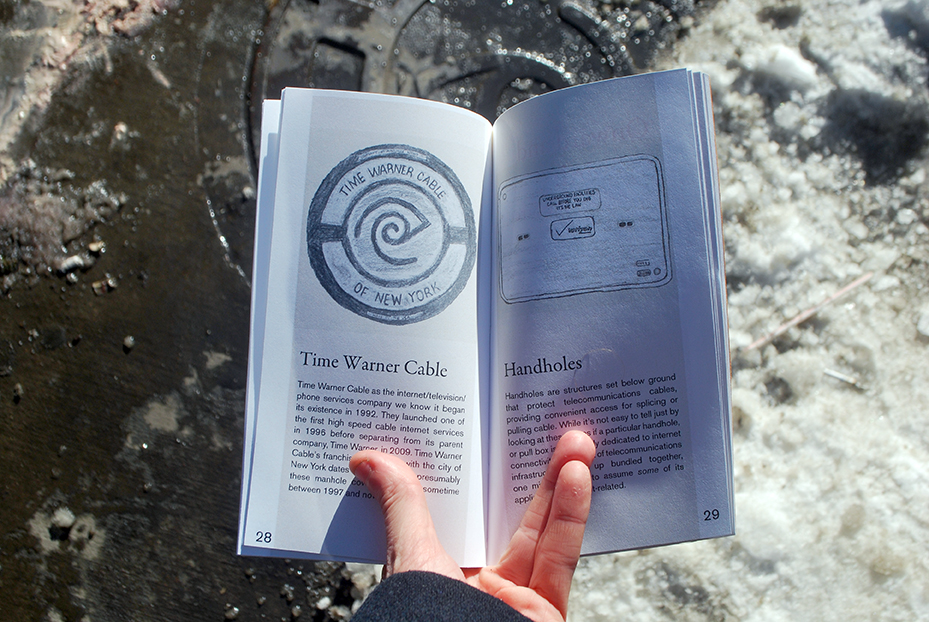

Ingrid Burrington, Networks of New York: An Internet Infrasructure Field Guide (2015).

Ingrid Burrington's web project Seeing Networks—now a book titled Networks of New York: An Internet Infrastructure Field Guide—functions in precisely this manner. It is a guide towards the interpretation of infrastructure, not psychogeographically, but literally. It translates the meaning of symbols scrawled in spray paint on sidewalk, of the foundry-forged impressions of access hatch covers, of the injection-molded plastic housings of radio antennas. Even if we can't enter the tunnels and secure facilities of this infrastructure, we can take this knowledge with us on the street, as we walk over the crust of the city which conceals it.

The knowledges that we ought to be studying are not always those we are intended to see, but we must seek them out, turning technology back against itself. Natalie Jeremijenko's classic project, BIT Plane, collected a video feed over closed campuses of Silicon Valley corporations in 1997 and 1998, utilizing a then cutting-edge aerial camera to show the areas of technological creation that were not available for public view. The film just grazes the surface, showing the outline of the buildings and not their contents. But compare it to an official aerial footage reel, the publicity film Wings Over Water, produced by the California Department of State Water Resources to showcase the California Aqueduct system. The difference in symbolic value between what you are meant to see, in smooth, gliding vistas with a New Age music score, and what you are not meant to see, depicted in pixelated, crash-prone, downward-gazing video, is quite clear.

![]()

Bureau of Inverse Technology, BIT Plane (1997-8). Still frame from documentation video.

The strange, contemporary intersection between designed intention and the hidden and visible is one of many knowledges situated all around infrastructure sites. And yet, the strange thing about hard power manifested in public infrastructure, is that as much as it is secured and classified, it is never truly invisible. As Trevor Paglen has pointed out, "Secrecy is a self-contradictory thing...If it has to be made out of the same stuff as regular stuff, it has to reflect light." By shifting focus from the informatic realm to the situated, material one, infrastructure researchers often gain greater knowledge. James Bridle's Drone Shadow project counters the secrecy of the US military's drone strike programs with the material fact of their existence: the life-size silhouette of a drone, painted on the ground in a public space, in white lines. His Dronestagram project takes freely available satellite imagery from drone strike sites cataloged by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, much of their research done using a network of reporters in the local areas where the attacks occur. Trevor Paglen's NSA-Tapped Fiber Optic Cable Landing Site, Mastic Beach, New York matches slides from leaked NSA sources to photographs of the beaches mentioned in the reports, attempting to bridge the knowledge gap between the government's war-room thirst for data, and the actual landscape where these quasi-legal infrastructural appliances are installed.

The vast number of projects that could be mentioned, described in detailed terms of how they specifically attempt to situate knowledges of infrastructure, is overwhelming. There seems to be an insatiable curiosity for these sorts of explorations among a certain intellectual set, a real desire to be made aware of uncomfortable truths. Walter Benjamin is perhaps the patron saint of such projects. From theorizing the liberatory potential of mechanically reproduced art to his massive, unfinished cultural-historical study of Parisian architecture in the Arcades Project, this flâneur of libraries is the infrastructure researcher's angel of history, inspiring future generations to extend turbine wings into its storm.

Benjamin committed suicide at a border crossing, fleeing prison and death at the hands of the state. Researchers produce books, but the infrastructure produces bodies, whether it be immigrants pushed out to the sea or factory workers held back from leaping from roofs.

With so much at stake, researching infrastructure is no simple task. It must be the political goal of situated knowledges to repair infrastructure's human mechanisms while dispelling the futurist aesthetics of technological acceleration, of utopian mastery, of authoritative control from the level of boilerplates on up. The situated researcher must dispute both the informatic and physical prisons, the construction of which we are even now funding, and uncover those who are being buried in the progress, without falling into the trap of implied neutrality. Haraway suggests a coding trickster—a shadow spirit, operating beyond the bounds of good and evil, equipped with enough knowledge of our objects' codes in order to manipulate them—might be model for escaping of our current binds, but one thinks the world of 2015 might have had as much of self-appointed tricksters claiming great coding power as it can stand. No masks, no tricks, no mere aesthetics will reclaim our infrastructure. Only knowledges, situated and amplified as we can.

Everyone leaves traces in infrastructure, like the artifacts of the Korean Workers' Museum in Sekula's Fish Story. Whether an artist, writer, or social scientist, the researcher who glimpses otherwise hidden roles bound up in the networks of contemporary capitalism can't help but be fascinated, even if they are also left mortified, depressed, and powerless in the face of what is seen. No book or project will reveal the infrastructure totally, or solve all the problems. But by looking in the crawl spaces, being willing to get one's hands dirty, to crawl a bit, to let one's eyes adjust to the shrouded places, the researcher begins to make infrastructure the structure it is meant to be.

![]()

Allan Sekula, Volunteer on the Edge (2002-2003), from the series "Black Tide/Marea Negra."

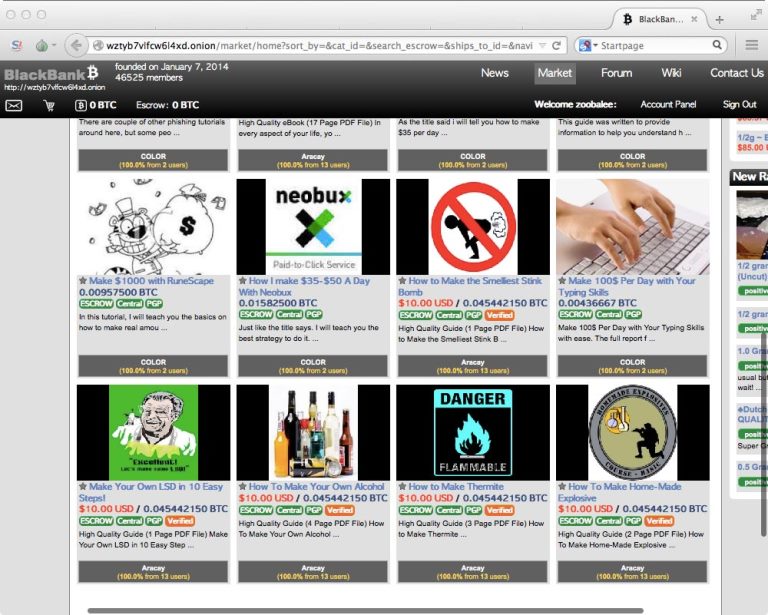

The one that got me. It seemed about as legit as anything else on the deep web.

The one that got me. It seemed about as legit as anything else on the deep web.