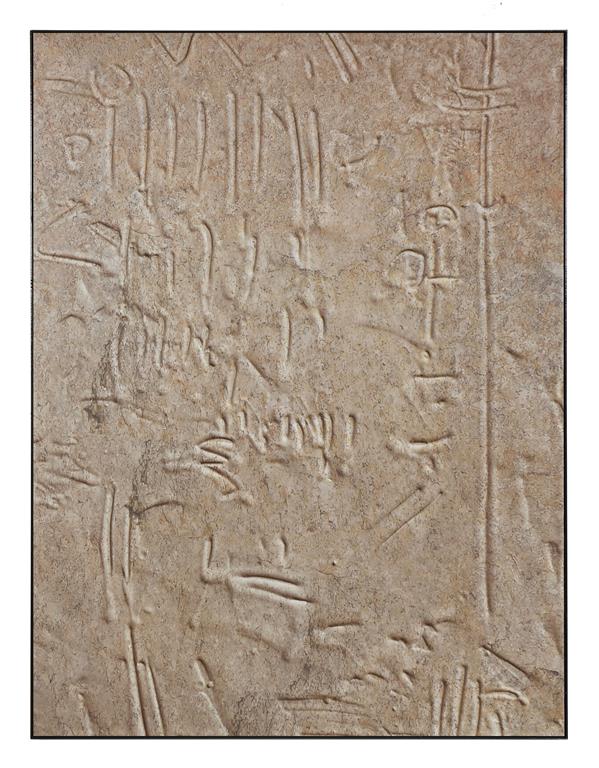

![]()

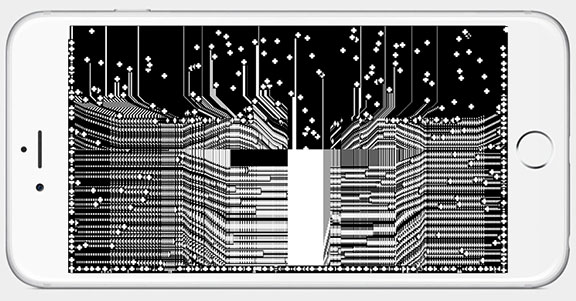

Joel Ford for whitneybiennial.com, as seen in 2015 on Chrome for Mac. Photo: Heloise Cullen.

One story of whitneybiennial.com opens at the electronicOrphanage (EO) in Chinatown, Los Angeles. Founded in 2001 by artists Miltos Manetas and Mai Ueda, the now-defunct EO was once a small artist-run project space on Chung King Road, a pedestrian pathway dense with independent galleries and studios. Until its demise in 2004, the "Orphanage" remained a stark black cube, completely barren if not for a white screen where digital art was occasionally projected, typically when neighboring galleries hosted opening receptions over drinks. For the most part, the space was a kind of laboratory for a group of artists, curators, and critics with a shared interest in the computer and digital culture—the "Orphans." It was here, sometime in February 2002, that a plot to cybersquat the Whitney Biennial began to take shape. Or at least this is how Manetas, the project’s architect, remembers it.

![]()

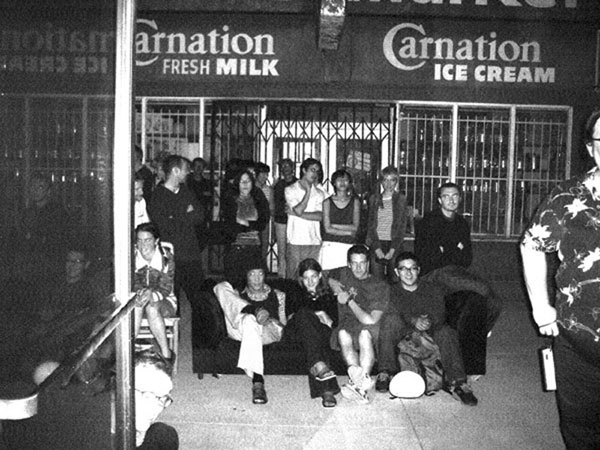

"Orphans" at the electronicOrphanage, Chinatown, LA (2001-2004). Source.

According to Manetas, the idea transpired from his exchange with art critic and fellow Orphan, Peter Lunenfeld. Less than a month away, the Whitney's 2002 Biennial was the focal point of their conversation, in particular the museum's heightened curatorial interest in emerging internet art forms. This seemingly ordinary chat eventually segued into an ambitious plan: to stage a net art show as an online foil to the 2002 Whitney Biennial. In time, the project developed into a full-on counter-exhibition, which would be hosted on the website whitneybiennial.com and installed IRL as a physical intervention, where a fleet of twenty-three U-Haul trucks, projecting artworks from the website, would blockade the Whitney Museum during the private opening reception of the Biennial.

![]()

The electronicOrphanage, (September 2001). Photograph by Peter Brinson. Source.

Like most Orphans at the EO, the works eventually displayed on whitneybiennial.com were predominantly identified with the currents known as Telic and Neen. Neen and Telic were closely related but distinct art brands, both devised in 2000 by the branding agency Lexicon at Manetas's request. In his elliptic explanation, "nature is Telic while miracles are Neen." Telic was more serious, more predictable, and readily identifiable; its aesthetics were firmly grounded in the capitalist market, its products were familiar and reproducible, at times channeled in commodities. Neen, on the other hand, was somewhat inexplicable, impossible to pin down, hard to recreate; it described a cathartic sensibility generative of creative epiphanies and breakthroughs: an artistic affect rather than a practice. While the definitions were fluid, at least one thing about the terms can be said with some certainty: by integrating networked technology with commercial design, Neen and Telic artists bridged many of the political and aesthetic chasms separating tactical media from proprietary software, net art from high-end fashion, and, ultimately perhaps, internet counter-cultures from consumer capitalism.

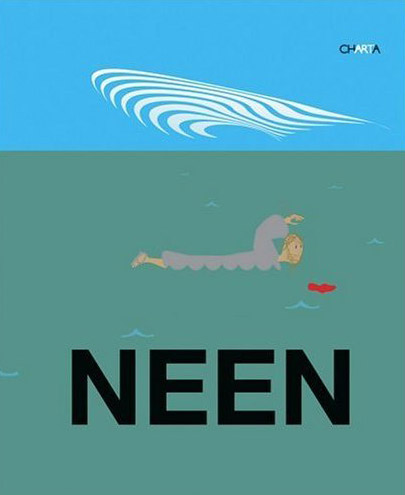

![]()

Cover of Manetas’s book, Neen: New Art Movement (Edizioni Charta: Milano, 2006). Source.

Contrary to most net art trends of the 1990s and early 2000s, Neen and Telic involved an unabashed embrace of commercial technology and corporate culture—the former as a production tool, the latter as a conduit for political critique. More often than not, Neen artists produced deeply ambiguous works that, while branded like a pair of Calvin Klein jeans, were displayed as single-serving websites identified by Top-Level-Domain (TLD) websites hosting multimedia graphics inspired as much by video-games as by Prada and Balenciaga, frequently designed with Adobe Flash.

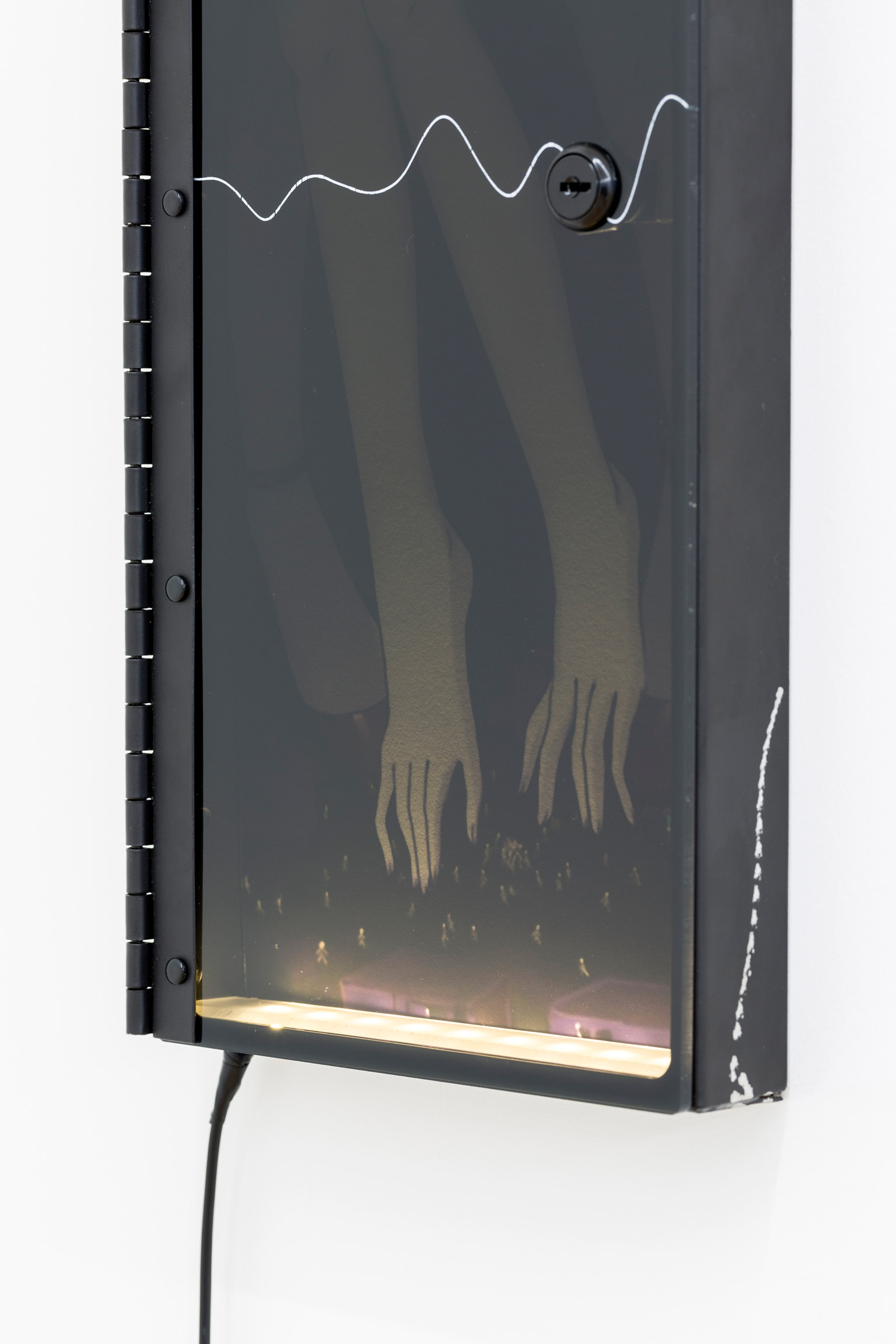

![]()

In one of the last installations at the space, the EO was transformed into a storefront where a phone number was projected onto a large screen, calling the number prompted a Neen artwork to appear on the storefront window. Source.

![]()

EO storefront screen displaying an artwork by Mike Calvert generated by anonymous phone calls. Source.

My research on whitneybiennial.com started last May, when I was asked by Michael Connor, Rhizome’s Artistic Director, to work on a piece Nate Hitchcock had begun writing. Michael gave me Nate's notes and a response from Manetas himself, a generously offered personal narrative that—though it was rife with pleonasms and hyperboles—I first took at face value. In retrospect, however, this was a naïve assumption: not because Manetas shouldn’t be trusted, but rather because I missed the work his story performed in the project. The more I read on whitneybiennial.com, the more I corresponded with curators and artists involved, the more variations on the history of whitneybiennial.com came forth. Eventually I came to see that this contested brand mythology surrounding whitneybiennial.com, oscillating between fact and fiction as it does, can be thought of as a crucial formal feature of the project. In the words of Benjamin Bratton, "It is in molesting the Reality Principle that [Manetas’s] work takes the greatest pleasure." Because I share Bratton's sentiment, it is worth going into Manetas's story in detail.

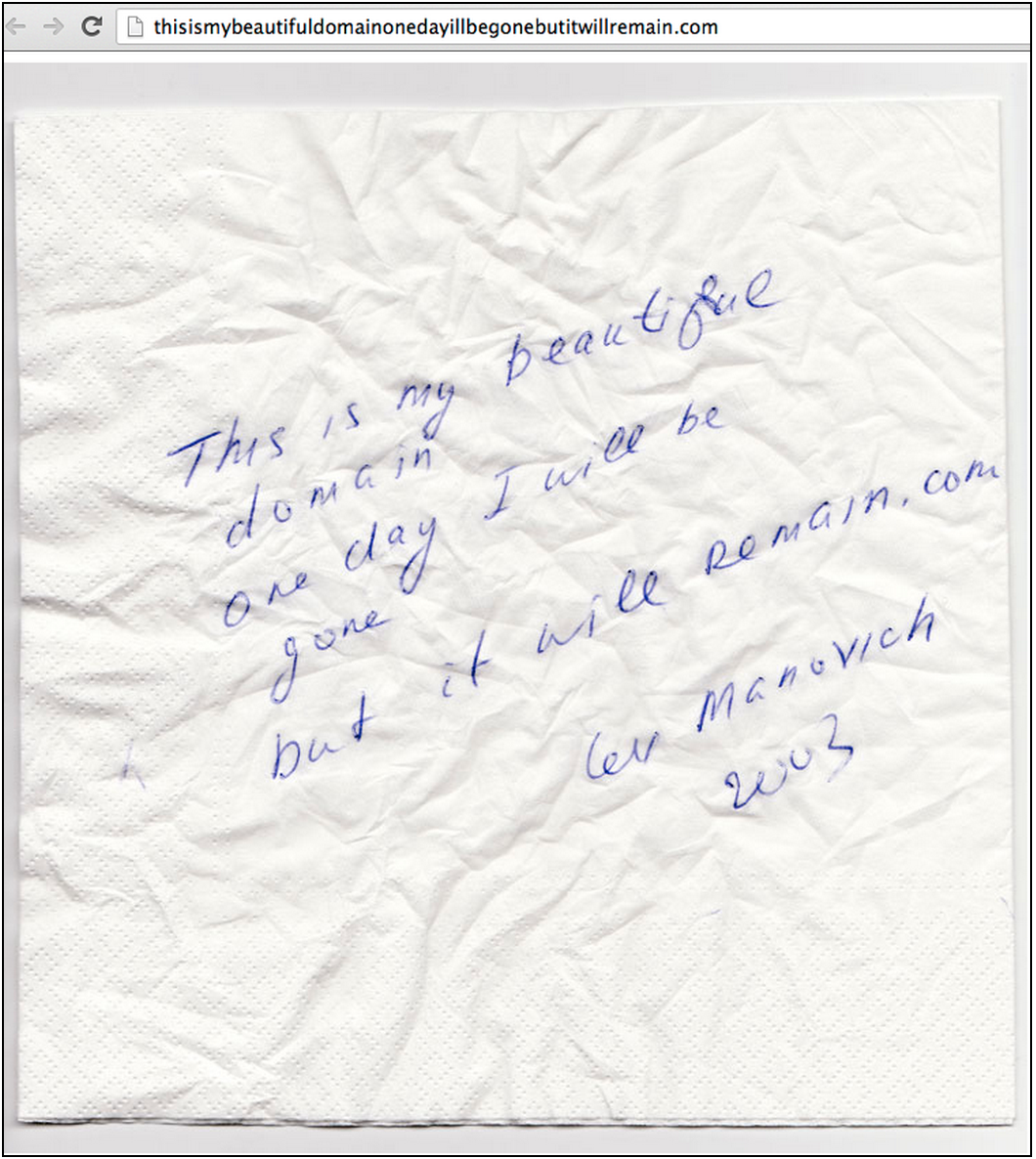

![]()

Lev Manovich, thisismybeautifuldomainonedayiwillbegonebutitwillremain.com (2003). Part of the electronicOrphanage net art collection. Source.

A Strange History of whitneybiennial.com

According to Manetas, whitneybiennial.com resulted from a series of serendipitous events taking place between LA and NYC through the course of February 2002. During their conversation at the electronicOrphanage, Manetas told Lunenfeld of his dissatisfaction with the Whitney’s selection of net art for the 2002 Biennial. His dismay appears to have been lodged in his perception that, by omitting Neen artists from the show, the museum had consequently failed to recognize it as an important and unique strain of web-based art at the time. Indeed, the artworks exhibited on whitneybiennial.com, most of which were designed with Flash, contrasted with the works featured in the Whitney’s 2000 and 2002 Biennials, which were often more technically sophisticated. When Manetas proposed curating an online counter-show, Lunenfeld suggested hosting it on "whitneybiennial.com," which, surprisingly, was available at the time. In a matter of minutes, the domain was registered to Manetas and the project was on its way.

Later that month, Manetas emailed Lawrence Rinder, chief curator of the 2002 Biennial, with an overview of his ideas. He claims that no more than ten minutes went by before Rinder responded enthusiastically, expressing genuine interest in the project. The following morning Manetas was on a plane to New York City.

That day, Manetas met Rinder in the Whitney’s iconic Breuer building on Madison and 75th. Looking out from his office window, Rinder drew Manetas’s attention to an empty Chase Bank branch across the street: "I can help you to get permission to exhibit the internet art over there. You can install a few computers and monitors, maybe a projector."

After considering Rinder’s proposal for a moment, Manetas remembers replying with a frenzied sort of politesse: "Thank you, but making a Salon des Refusés 2002 is not exactly our intention. We have our Space: it is the internet itself, larger and a lot more powerful than the Whitney." Looking through the same window in Rinder’s office, Manetas saw a U-Haul truck parked opposite to the empty Chase branch and, within seconds, came up with an extravagant, off-the-cuff plan to stage his show as a public installation. "We are going to use 23 U-Haul trucks […] to surround your exhibition the day of the opening," he told Rinder. The U-Haul trucks would be transformed into large-scale, moving screens for the presentation of a selection of works, many by graphic designers, programmers, architects, and "Neenstars," curated by the likes of Alex Galloway, Lev Manovich, Marisa Olson, Patrick Lichty, and a host of other well-known figures in the net art world. As Manetas told Rinder that day: "The trucks will be looping around the Whitney tirelessly, each carrying a number of very special webpages."

While announcing his plan to disrupt the Whitney’s show, Manetas recalls leering at Rinder's collection of "obsolete" printed matter cluttering the curator's office, issues upon issues of Artforum and Art in America, which he interpreted as physical placeholders for the Whitney’s "antiquated" curatorial practice, tokens in the symbolic economy he was determined to defy. Before reaching for the door, likely with the allegorical magazines still in sight, Manetas turned to Rinder and said: "We consider webpages to be the real art of our days."

![]()

Miltos Manetas (2013). Source.

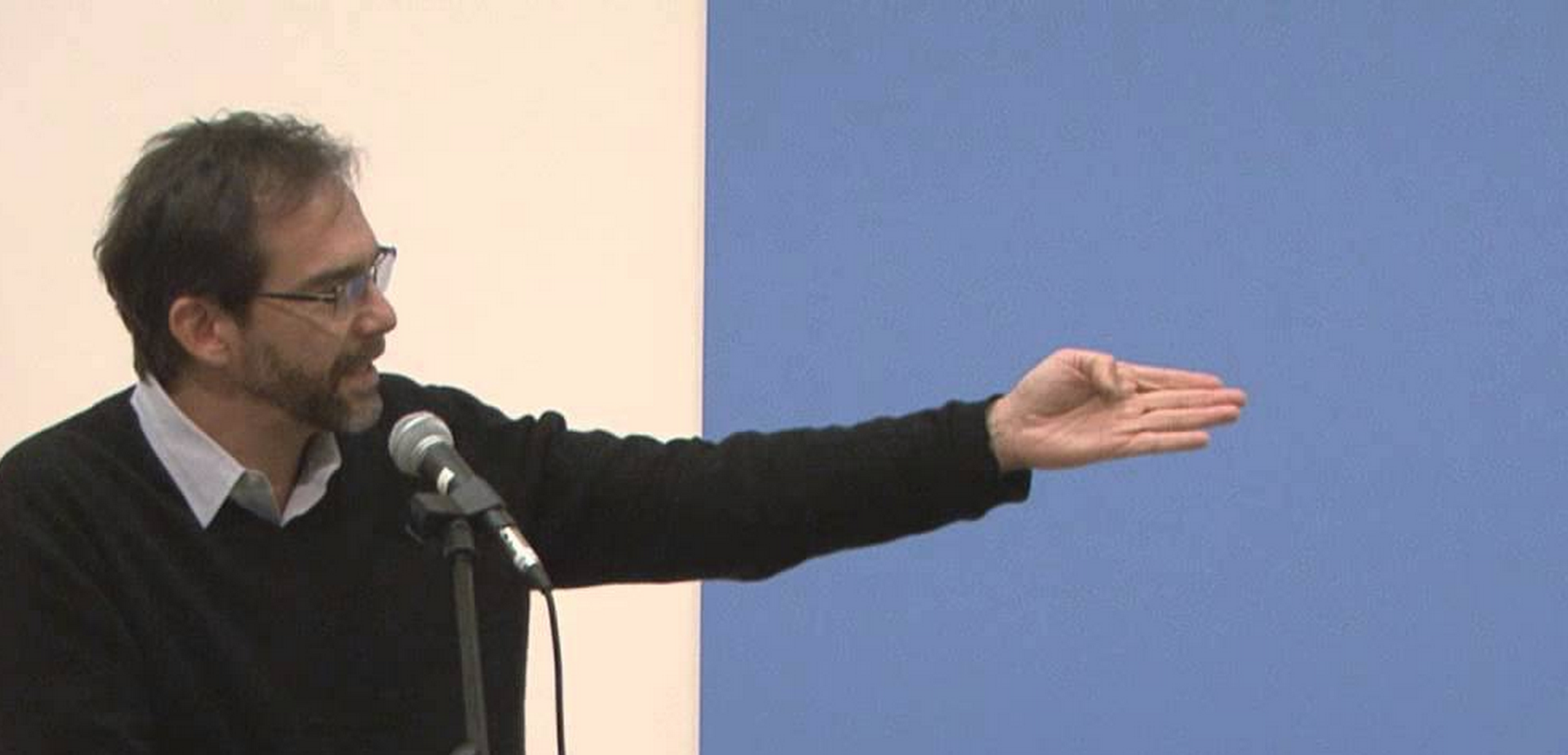

![]()

Lawrence Rinder (2013). Source.

The next day, Manetas describes being surprised by a wave of phone calls and emails that poured in from alarmed gallerists, curators, critics, and artist-friends, all counseling him against the U-Haul scheme. Matt Mirapaul, from the New York Times, allegedly fanned the flames by describing Manetas’s installation as "the Internet against the Art System."

For Manetas, the U-Hauls were never the point. The real aim of the counter-Biennial was to circulate works that he deemed important and representative of a marginalized trend in early-2000s net art, without necessarily being "net.art per se." His take on net art was quite particular; romanticizing Adobe Flash as a "creative bomb," Manetas was convinced that new internet art practices were emerging. If artists working in Flash were perhaps more readily overlooked by the museum sector because their chosen tool was associated with commercial culture, then a similar attitude may have been reflected in the Whitney's casual disregard of the similarly debased .com domain. "In a sense," Manetas writes, "it was Whitney itself that commissioned me to make an anti-show online, by failing to register its own .com domain." This was commercial web aesthetics positioned as outsider art, long before they became the postinternet mainstream.

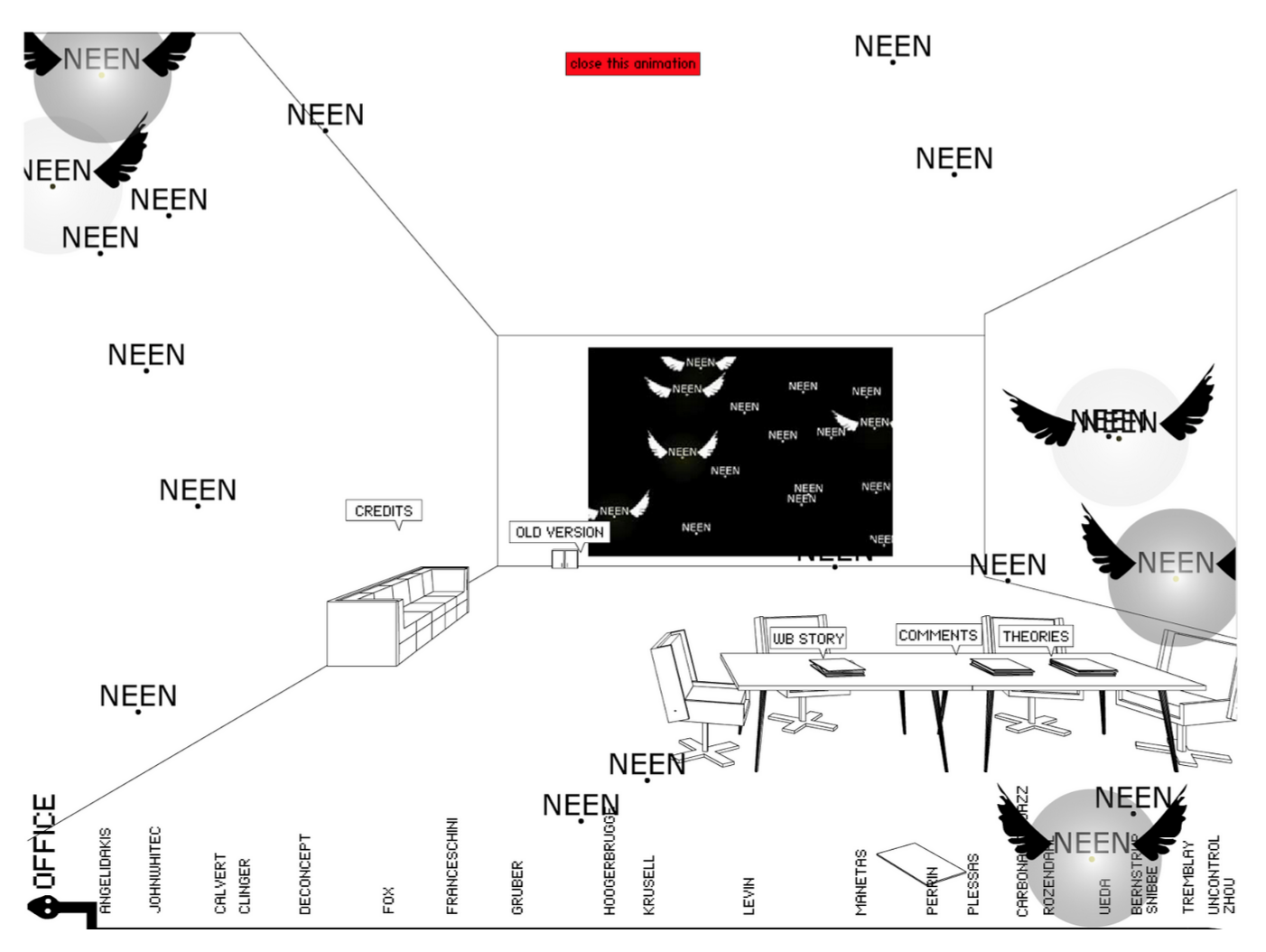

![]()

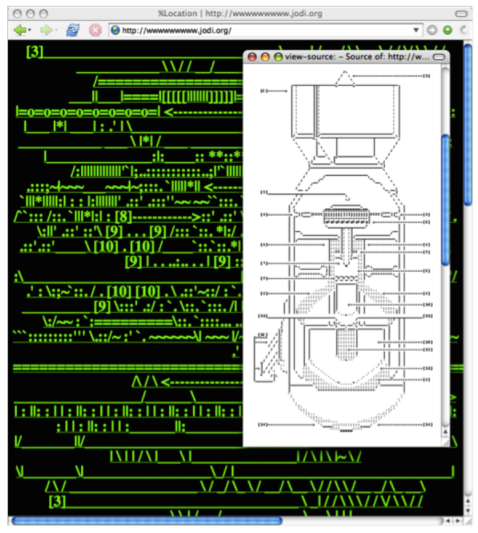

Screenshot from whitneybiennial.com (2003 version).

On Tuesday, March 5 at 7:00 PM, the 2002 Whitney Biennial opened its galleries to invited guests and members in the Upper East Side. Onsite, not a single Neen U-Haul truck marred the private reception's high art gleam. Online, however, the counter-Biennial held its ground (and still mostly does to this day, despite the occasional missing plug-in). The 2002 version of the site, designed by carbonatedjazz (aka Alexander Chen), featured HTML tables with thumbnails or embedded .swf files for each artists. The works could be opened in full screen from there, or sent to a "turntable" (created by Michael Rees) where they could be overlaid and, yes, remixed, in true early 2000s style. In 2003, a new version was created for a CD-ROM published by the Italian Magazine POSH; this version placed the work in a navigable museum-like environment. Both iterations are carefully considered classics of the online exhibition genre.

Whitneybienial.com: History as Fable

Given the importance of branding to Manetas's practice, I reached out to a few other people involved in whitneybiennial.com to hear their stories. Quickly, the contradictions began to pile up. It is unclear, for instance, whether Manetas's encounter with Rinder, described with so much clarity and passion, was exactly as Manetas claims. At any rate, after I emailed Rinder asking about his exchange with Manetas, this is what he wrote back:

![]()

"None of that sounds familiar to me. I may very vaguely recall him saying something about a project with trucks but can't recall any details...I certainly did not contact the NYT." Larger screenshot.

Additionally, Patrick Lichty, a co-curator of whitneybiennial.com, says that Manetas contacted him about the project in December 2001. Meanwhile, Marisa Olson says she was invited to curate the show as early as November 2001; she was among the first curators invited to join the project and, in many respects, her recollection of whitneybiennial.com is an intriguing foil to Manetas’s story. "U-Hauls were part of the initial plan—as described to me by Miltos," she recalls. "From the very first minute," she continues, "[Manetas] described [his project] as renting U-Hauls [...] and having the back doors open, then projecting work onto a screen. Miltos was especially obsessed with artists working in Flash animations. He wanted me to roundup Flash artists. Then the trucks were going to circle the block projecting the work during the opening." Per Olson, the project was already underway, with the Neen U-Hauls as its centerpiece, several months before the meetings with either Lunenfeld or Rinder were supposed to have taken place.

Pointing out these contradictions only serves to demonstrate that storytelling played a role in the project. If the history of whitneybiennial.com can be read as a kind of net art fable, that's certainly not because Manetas or anyone else involved was purposefully malign or disnohest, but because the project itself was, and remains, a performative internet fantasy. As Olson remarked:

![]()

"Yeah. It is all a performance for Miltos. ;)" Larger screenshot.

Much of what is critical, even "radical," about the project stems from its more playful and performative elements. In Manetas’s own words, "when reality is not inspiring enough, you need to push it."

At the same time, though, when I asked Olson whether she thought of the project as a political intervention, she offered a pointed critique:

Maybe in its initial conception, but not considering what happened.... Here's what actually happened.... I busted my butt to reach out to 'Flash Artists' and get them excited to be part of this thing that was but wasn’t legit and was AT but not IN the Whitney Biennial. I promised them it would look the way they wanted and be handled professionally and be seen. And it was never seen. I was going to grad school in London at the time and couldn’t be present at the opening. I started contacting Miltos for photos, feedback, etc. Artists on the ground in NYC started complaining to me that they never saw the trucks, artists abroad were sending me panic emails.

Miltos was at first unresponsive, then said it was too hard to get the trucks and projectors, then he said he never meant to do it at all. Given the order of responses, I felt like it was an excuse and he was just trying to sound punk and cool, but that could also be a performance of its own kind?

Meanwhile, I started hearing rumors and started wondering what was true, what was generated, what was spun, when the rumors were set into motion in the first place... I heard that I wasn’t the only curator, but I never heard any other names or met anyone. I also heard that Miltos was in attendance inside the museum opening and that he had something like 5 guest passes (which is pretty baller) and that he was using them to sneak people in and out of the opening all night...

For me it was hard because I love providing access to ghettoized artists, but I felt pranked, the artists I invited were pissed at me (some for a long time) and I had no solid response, and in the end I felt a bit left out of the secret boys club.

Perhaps Manetas did not push reality quite far enough.

The Politics of Neen Aesthetics

As an intervention, whitneybiennial.com bears evident likeness to the tactics used by the Women's Art Committee (WAC) throughout the 1970s. The Committee sought to rectify the overwhelming predominance of male artists in the Whitney Annual by demanding that at least half of all artists in the exhibition be women. To this end, the group staged a series of artist demonstrations, sit-ins, and public installations—one of which was a slide show of feminist artworks projected on the Whitney’s façade. Additionally, Manetas’s counter-Biennial project draws on a similar, albeit more straightforwardly militant, online intervention against the Whitney Biennial by the collective RTMark. After being invited to exhibit their website in the inaugural net art section of the Whitney’s 2000 Biennial, RTMark not only auctioned their invitation to the private reception on eBay (which went for $8,400), but also opened their online exhibition space, on whitney.org, to anyone who wished to have their website displayed in the Biennial’s online gallery portal.

While whitneybiennial.com unequivocally draws on the institutional critiques staged by the WAC and RTMark, it is also categorically distinct from both. In fact, reading whitneybiennial.com with reference to the WAC and RTMark, or other similar art historical precedents, fails to convey what is particular to Manetas's intervetion, namely, its quintessentially "Neen" aesthetic. I find that in order to understand the political thrust of whitneybiennial.com, it is helpful to turn to the formal and conceptual elements that make it a Neen work of art, most notably, its ambiguous relation to postindustrial capital.

Building on Frederic Jameson's concept of the "double hermeneutic," which allows a work to be interpreted as both a reinforcement of and a challenge to asymmetries of power, Bill Nichols noted in 1988 that, to appreciate the political transformations in the modes of cultural production effected by cybernetic technology, cybernetics must be interpreted through a "double hermeneutic of suspicion and revelation." In other words, unveiling the political content of cybernetic art demands reading cybernetics in light of its "dominant tendency toward control" while appreciating, at the same time, its "latent potential toward collectivity." If, as Nichols suggests, a double hermeneutic is an indispensable tool for diagnosing the politics of artistic production within such dialectical systems as cybernetics or capitalism, then a similar ambivalent analytic framework should be no less useful for understanding the political matter of artworks created on the internet—whose deep-seated contradictions are numerous. Whatever the formal, technical, and conceptual merits or shortcomings of Neen art may be, its political efficacy finds its most biting expression in its ambivalent approach to the internet, one that is evinced in Neen's embrace of commercial design, proprietary technology, and corporate culture as fundamental components of online artistic production and critique.

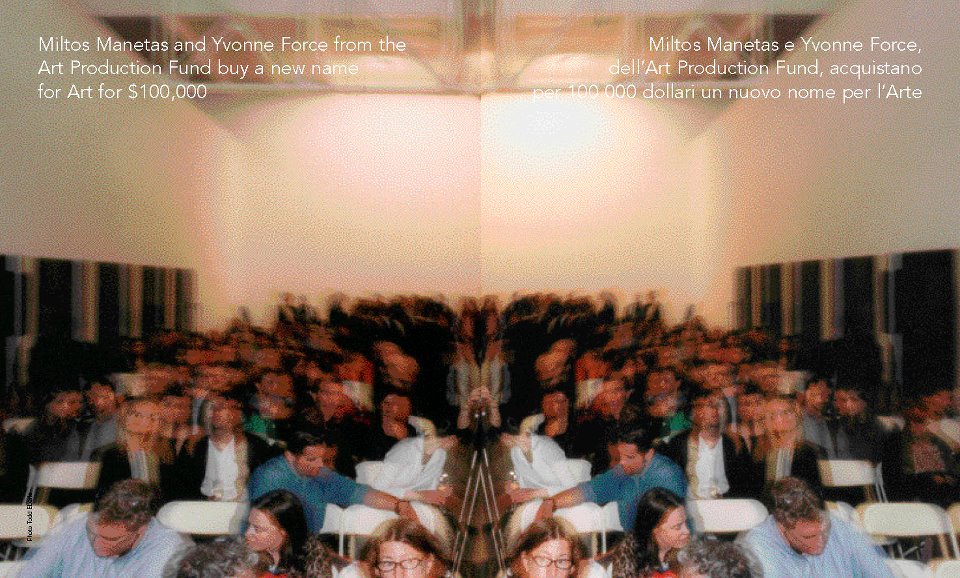

From its very inception, Neen has been intimately and conspicuously interlaced with consumer capitalism. The term was in fact coined neither by art historians nor critics, but by Lexicon, a corporate branding firm responsible for creating many of the world's most famous brand names for such clients as Mercedes-Benz, Intel, and Apple, to name but a few. Combined, Lexicon's brands have generated over $350 billion in sales revenue since 1982. Given the company's financial success, it is hardly shocking that Lexicon charged $100,000 to re-brand contemporary net art, an amount paid in full by the Art Production Fund and venture capitalist Louis Marx Junior. More than merely coining the word Neen, Lexicon also identified the types of artistic dispositions that defined it. According to David Placek, Lexicon's CEO at the time, "'Neen' transcends art. It's more a state of mind than a form or school of art." Alongside "Neen," the company also coined the term "Telic" as a distinct yet related alternative to Neen. At the end of the day, however, it was Manetas's choice to purchase "Neen" as the "new name for art." To be sure, many of the mysteries surrounding whitneybiennial.com as well as the aesthetic specificities of Neen art are demystified by Lexicon's corporate philosophy: "The single most important value of a name is its storytelling ability." More importantly, a brand—be it Apple, Obama, or whitneybiennial.com—is only able to tell good stories if, and only if, it does three things: "Get their attention. Make it interesting. Tell them something new."

![]()

The term “Neen” was introduced in a conference held at the Gagosian Gallery in NYC on May 31, 2000. The panel comprised Yvonne Force (Neen project's producer), Manetas, Lunenfeld, David Placek (President of Lexicon Branding), J.C.Herz (writer and journalist), Steven Pinker (MIT Professor and writer), and Joseph Kosuth (artist). Source.

Since their nascent stages, then, both Neen and Telic were inextricably enmeshed in the logic of consumer capitalism, both aesthetically and conceptually. Expanding on Lexicon’s initial definitions, Manetas notes that Telic "covers pretty much everything that has to do with technology, [...] all kinds of cool and not so cool design[s], such as the Apple Computer but also IBM and Microsoft, fashion [labels] such as Prada and Calvin Klein." "Nike," he continues, "is Telic-goes-to-the analyst, Adidas is classy Telic," and "Italian Vogue is a Telic Fashion Miracle." Neen, on the other hand, is a "frame of mind" created in large part by new media technology, mostly video games, computers, and the internet; it is closely associated with Adobe and finds its commodity equivalent in apparel designed by Nicolas Ghesquiere for the high-end fashion label, Balenciaga. As such, commercial design and fashion—rather than technology, coding, open source software, or more overtly political forms of cultural production—appear to be the central references in Manetas's own definition of the very artistic currents framing his project. As a result, and in its capacity as an online branded performance, whitneybiennial.com is, like Neen and Telic, conceptually, technically, and formally indebted to corporate culture: from its use of narrative as an advertising maneuver to its reliance on commercial software as a design tool.

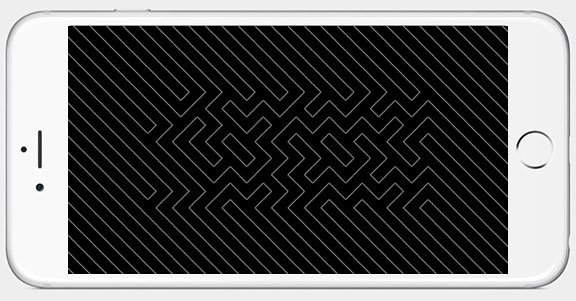

![]()

Rafaël Rozendaal, Falling falling, (2011). Source.

Commenting on the splash caused by whitneybiennial.com, Patrick Lichty foregrounds an important aspect of Manetas's practice: his use of the internet as a means to appropriate the marketing strategies and aesthetics of corporate or institutional brands, recreating them within his work. In certain respects, Manetas’s intervention in 2002 brings the more polemical aspects of Colin de Land’s curatorial legacy in dialogue with net art. De Land's provocative, though always humorous, defiance of the art market and its gatekeepers, as well as his interest in the politics and aesthetics of corporate culture as a vehicle for sabotaging both art and capital, are particularly notable. Much like the electronicOrphanage, a meeting place and studio for Neen scenesters, de Land's SoHo gallery, American Fine Arts, was another space where artists associated with oppositional artistic movements converged through the course of the 1990s, an "art world laboratory, hangout, and refuge," according to Roberta Smith. Both de Land and Manetas consistently transformed their spaces into sites for art protests through installations that sought to challenge the commercialization of art and the bourgeois ritual of opening receptions; while the EO often projected net art on its large white screen as a “counter-opening” while neighboring galleries hosted receptions, de Land allowed one artist to close his gallery for a month as a protest against the art market.

![]()

Brian McPeck, Lizzi Bougatsos, Spencer Sweeney, Souhi Lee, and Kembra Pfahler at de Land’s American Fine Arts (c May 2002). Source.

I found that reading whitneybiennial.com against the backdrop of Neen's political entanglements and anti-establishment references brings forth an alternative, and more compelling, answer to a pressing question: why the Whitney? If you recall from Manetas's story, one of his original explanations for targeting the Whitney was his dissatisfaction with its curatorial practice, more specifically, its selection of net artworks for the 2000 and 2002 Biennials. This is also how he justified the intervention to Olson back in 2001. "Miltos explained to me," Olson writes, "that he felt new media art and artists were being overlooked by the Whitney [...] and he wanted this project to raise visibility of these essentially 'outsider' artists by showing them outside of the museum into which they weren’t being let in."

As most readers involved with net art since the early 1990s can attest, the Whitney was one of the pioneering American art institutions of its scale to support net artists and curators in a sustained way. The museum’s early engagement with net art makes Manetas's choice to target the Whitney, as well as his dismay with its curatorial practice, all the more puzzling.

While its representation of net art practices was by no means comprehensive, the Whitney was, at that time, one of the few American museums seriously invested in bringing net art into its collection. Acquiring its first net art piece in 1995 (Douglas Davis’s The World’s First Collaborative Sentence), the Whitney was also among the first large-scale art museums to significantly incorporate such work into its curatorial program. In the year 2000, for instance, the Whitney devoted, for the first time in its history, an entire section of its Biennial show to net art. Two years on, in the 2002 Biennial, ten original artworks were exhibited online under the "net art" category, which was supplemented by a discussion panel, in collaboration with the "Netart Initiative," featuring all net artists in the exhibition. That same year the museum launched artport: its official portal to, and online gallery for, commissioned net art projects. Curated by Christiane Paul, the Whitney’s adjunct curator of new media, artport was (as much then as it is now) the institution’s central platform for the online exhibition and digital preservation of internet art.

Looking at whitneybiennial.com through the lens of Neen politics, though, the Whitney becomes less the target of Manetas's critique than its vehicle. The Whitney was an advertising vessel, chosen for its immeasurable value as a fine arts brand name and deployed as a means to establish Neen as a relevant, recognized, and accepted trend in contemporary art. Like a counter-cultural leech, Manetas capitalized on the institution's reputation, influence, and widespread popularity in order to promote his own curatorial agenda, while at the same time critiquing the institution's authority as an artworld sentry. In essence, what Manetas did to the Whitney in 2002, Art Club 2000 (under de Land's direction) had done to the Gap in 1993, Kenneth Aronson to Hell.com in 1995, and RTMark to GWBush.com in 1999. Like all these brands, "The Whitney Museum of American Art" and "The Whitney Biennial" were valuable brand names, which Manetas deployed strategically to, among other things, attract attention, publicity, and curiosity.

One common attack levelled against whitneybiennial.com is rooted in an interpretation of the Whitney as a target, rather than conduit, of Manetas's critique. Curt Cloninger expressed this position in 2004 as a response to Patrick Lichty: "My problem with this particular 'intervention' is that it doesn’t really dis the Whitney." As such, Cloninger’s "problem" seems to proceed from a misunderstanding of Manetas's goal, which was not to "dis" the Whitney, but to "use" it. Manetas took on the Whitney as a performative meditation on the institution's brand value, which he did by appropriating it from the outside, by cybersquatting the Whitney’s domain without the museum's consent. Cloninger concludes his own reading of whitneybiennial.com by arguing that RTMark's hack at the 2000 Biennial was a "much more focused and interesting conceptual tactic." This is yet another common move: to understand the political efficacy of whitneybiennial.com only in contrast to RTMark's intervention two years earlier. Even Matt Mirapaul of the NYT ended his piece on Manetas's counter-Biennial by crowning RTMark’s project as "the most effective commentary on the museum world's Internet aspirations," whereby "an exclusive domain became a populist website." Indeed, one of the reasons why RTMark’s project is seen as more "effective" (Mirapaul) or "focused and interesting" (Cloninger) than Manetas's appears to be, as Cloninger suggests, because the latter failed to be sufficiently critical of the Whitney. But, if the reaction of those targeted by institutional critiques are at all indicative of whether or not the project was "sufficiently critical" of its target, then it seems that the Whitney was as unaffected by Manetas as it was by RTMark. Maxwell L. Anderson, the Whitney’s director and one of the Biennial curators back in 2000, welcomed RTMark’s intervention, noting that "opening the site to submissions from the public is in accord with RTMark's concept, which is to provide an information brokerage—with limited liability—and public forum for Net activism." While I agree with Cloninger's and Mirapaul's praise for RTMark, I am not so much interested in assessing whitneybiennial.com as a more or less successful RTMark hack. What I am interested in is to think through the specific ways in which the formal and aesthetic (Neen-based) qualities of the project are fruitful avenues for reading whitneybiennial.com politically, in its own right.

![]()

Art Club 2000, Times Square/Gap Grunge 1 (1993). Source.

As finance and postindustrial capital overtook industrial manufacturing, the web provided companies with platforms—such as Top-Level Domain names—for enhancing their corporate branding strategies. The internet allowed brands to weave the use-value of their products as well as the lifestyle these commodities sustained into an accessible online narrative displayed in the company’s website. With the advent of e-commerce websites, advertising and sales became evermore connected. Unsurprisingly, TLDs and Adobe Flash were key creative tools in online branding strategies. This new corporate aesthetic, where material commodities, previously displayed as physical merchandise in storefronts, became virtually represented online as immaterial objects, was evident as much in capital as in art, a reality for the Gap and the Whitney alike.

Manetas was early to realize how profoundly this shift would also reconfigure artists' practices and rewire art's attention economy. For Manetas, the transformative potential of the web as a site for artistic creation and exhibition are found in two of its offerings: liberty for the artist and exposure for the artwork. "The Internet," he argues, "is for visual artists a platform to do their thing without making compromises and to show the output to the whole world. It presents an opportunity to move freely and to introduce one's work without the interference of gallery-owners and curators."

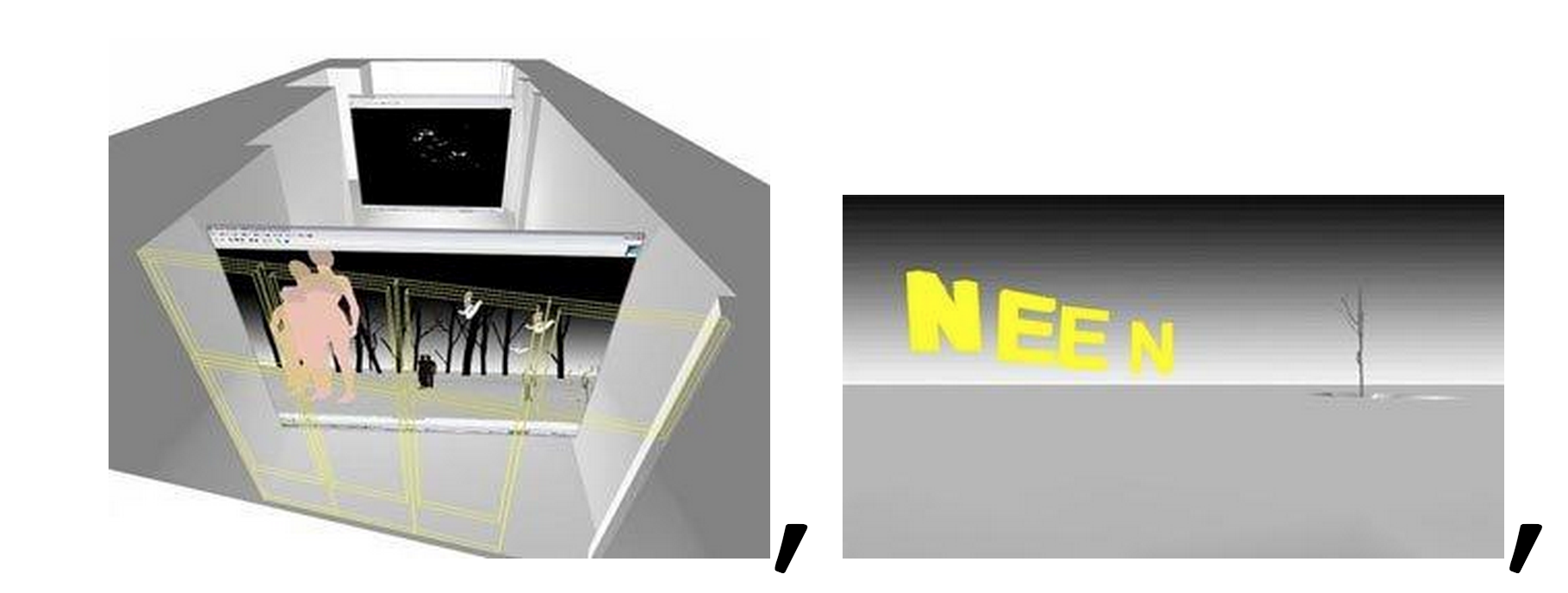

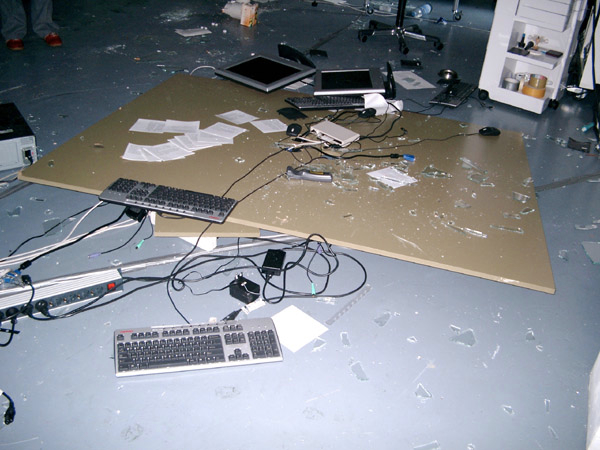

Even after whitneybiennial.com, the practices of branding, storytelling, and performance continued to drive Manetas’s artistic and curatorial endeavours. During the winter of 2002, he curated a group show titled Afterneen, featuring works by artists associated with Neen. The show opened at Casco Projects in Utrecht, The Netherlands on November 16, only to be mysteriously demolished two days later by what Manetas has called "a (digital) car crash."

![]()

Neen artworks from Manetas’s "Afterneen" show at CASCO (November 16 - December 15, 2002). Source.

A Google image search for the show yields digital photographs of a derelict office space packed with torn chairs, broken computers, and destroyed electronic appliances, alongside Neen posters and a glass door reading "CASCO." Given the specter of mystery that continues to haunt this exhibition, it comes as no shock that Afterneen builds on similar branding, performative, and mythmaking aspects of whitneybiennial.com. It is worth noting that the word "Neen," a combination of “screen” and "new," means "exactly now" in Greek. Moreover, if written in caps, "NEEN" is both a palindrome and a mirror-word, readable in all directions, including backwards and upside-down. As a palindrome and mirror-word, "Neen" elicits the experience of multidirectional movement; as a word in the Greek language, it denotes the present. Thus, much like Manetas's performative fables, the meaning and form of the word "Neen" challenge the linearity and temporality of historical narrative, the idea that facts can be recovered from the past, the natural ordering of chronology, and so on. In a similar vein to the Whitney intervention, Afterneen dabbled in a liminal and tenuous ontological space, at the vanishing point where hearsay meets evidence, history meets myth, and the internet becomes real. Like the U-Haul scheme, Afterneen tested the extent to which an actual exhibition could exist and cease to exist online—be constructed and destroyed materially through web-based narratives—without having necessarily existed physically.

![]()

Photograph from the opening of "Afterneen" at CASCO on November 16, 2002. Evidence that the show took place physically? Source

. ![]()

Photograph of CASCO taken after the "digital car crash" (November 2002). Source.

![]()

Photograph of CASCO taken after the "digital car crash" (November 2002). Source.

![]()

Photograph of CASCO taken after the "digital car crash" (November 2002). Source.

The fact that Manetas and other Neen artists were never given the Whitney’s seal of approval meant that whitneybiennial.com was faced with a considerable challenge: to show the art world that internet artworks made by graphic designers were just as valuable and relevant as those created by programmers and coders. Moreover, unlike RTMark and other net artists included in the 2000 and 2002 Biennials, artists involved with whitneybiennial.com did not necessarily adhere to particular tendencies and practices regnant among their contemporary net artists. While both Manetas and RTMark used web-specific tactics as a means to critique the asymmetries of power created and sustained by an institution such as the Whitney, only RTMark was able to deploy the cultural privilege of being affiliated with the Whitney brand name, since they were included in the Biennial. Manetas, on the other hand, was left to his own devices, having to appropriate the brand from the outside. It is no minor detail that, despite the movement's development within online cultures, Neen "is not 'net art,'" according to Manetas. In many ways then, if Manetas's intervention was in part meant to show the public and the Whitney that Neen art was an important and relevant web-based art form, he went about this goal by distancing Neen—technically, aesthetically, and conceptually—from net art. Perhaps the most evident distinction between whitneybiennial.com and other tactical interventions by net artists was in fact Manetas’s characteristically "Neen" embrace of corporate culture, which, as I stress above, is evinced in his preference for proprietary over open source software, his fixation in fashion labels, his fascination with commercial design, and, above all, his ambivalent approach towards the internet and late capital, somewhere between suspicion and revelation, as Bill Nichols so elegantly put it.

***

As the Whitney opened its doors to a select audience on March 5, 2002, Manetas says he stood at the entrance of the Breuer Building (or, according to rumor, inside as an invited guest) consoling disappointed artists and onlookers, reassuring them that his U-Hauls were actually present, but they were invisible. Much like the invisible cubes in Gino De Dominicis’s Second Resolution of Immortality (The Universe is Still), to whom whitneybiennial.com is dedicated, Manetas still holds that his U-Haul trucks were never meant to be seen, only heard as hearsay—as an entry in the probably meager annals of "net art oral history." But maybe Manetas’s fable, fantastic as it was, had a more concrete effect than eliciting terror and curiosity. By inscribing an immaterial art form within the physical space of his narrative, Manetas's project is also a crude and mythological meditation on the source of an art form’s influence and relevance, a commentary on the arbitrary value of physical objects in the context of an art world so profoundly organized by the financial and market-driven axioms of late capitalism. By foregrounding the extent to which an artwork’s "importance" is often enmeshed in the art object’s materiality as well as the physical space it inhabits, Manetas’s project reminds us of an old yet invaluable story about art's uneasy relation to the commodity form, its profoundly fetishistic allure, as well as its insidious and ambivalent ties to capital.

Commenting on the intersection between the physical and digital spaces of exhibition, Manetas remembers the events that led to the actual destruction of his Afterneen show through yet another, even more surreal tale. As the show unfolded inside CASCO, Manetas claims, a car operated in part by a human driver and a computer parking system lost control as the human operator became distracted while "making out with a young woman." The unruly car then accelerated into the gallery space, destroying everything in its wake. In the aftermath of Afterneen, no material remnants from the alleged show survived, not even the servers used to host the interactive "NEENWORLD" were spared.

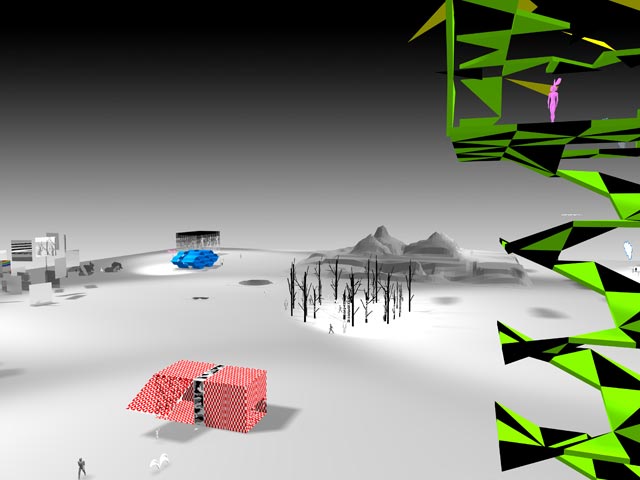

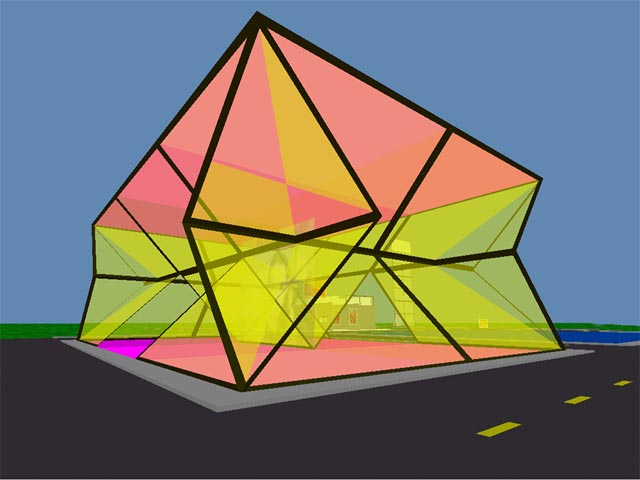

![]()

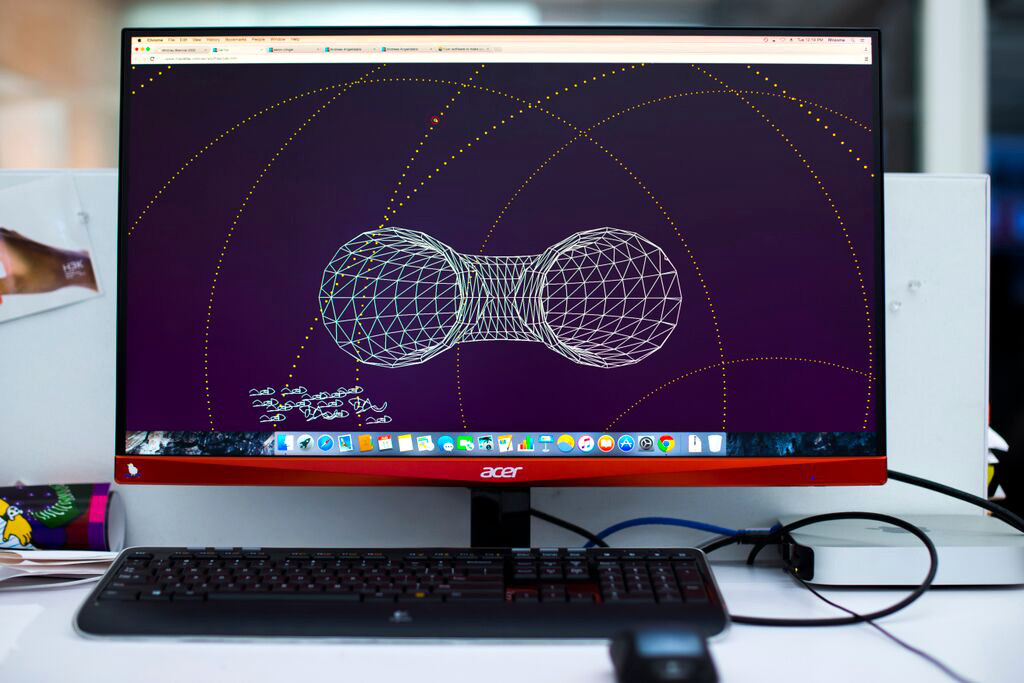

NEENWORLD, designed by Andreas Angelidakis, was a virtual-reality environment where members of the Neen movement could interact with each other online. Source.

![]()

Andreas Angelidakis and Miltos Manetas, Chelsea, created on ActiveWorlds platform (1998-2000). "Chelsea was a virtual city for art and architecture, a 3D community that included artists, curators, architects, institutions and galleries. It was a world that we put together with Miltos Manetas, to experience the new sense of space that the internet was providing. Architecturally the challenge was to design buildings on the spot and in a way that they downloaded fast, and registered on the short attention span of the internet user. This produced buildings based on the existing Active Worlds 3D library, buildings that could register as quickly as a logo." Source.

Upon receiving this news, Manetas describes feeling "surprisingly calm and even relieved." "From the beginning," he recounts, "destiny was showing us that the space of the internet, is not to be mixed carelessly with real space, that we can host the internet in real space." If there is any hope for the "materialization" of web-specific environments, Manetas notes, it most certainly does not lie in the material, ideological, political, and aesthetic domains of the "exhibition," as traditionally conceived by museums and galleries. For Manetas, "The essence of the web must be experienced on its native domain." Yet, despite Manetas's own take on the curatorial politics of net art, whitneybiennial.com was never exclusively exhibited online, the native environment of it artworks. Even if the U-Haul plot never materialized, Manetas managed to expand the medium of whitneybiennial.com, over all these years, from an online exhibition to a living brand lodged in a surreal net art fable.

All in all, the most adamant testament that whitneybiennial.com was a critical asset for net art practice is that, amidst its many physical, "real-world" fantasies of Upper East Side meetings, enlightening conversations at the electronicOrphanage, U-Haul Trucks, threatening intimations, whimisical outbursts, unscheduled bi-coastal flights, and so on, the internet was, and remains, the only "real" and "true" residue of the project. The liminality and uncertainty of the performance are thus checked by the historical certainty and ontological tangibility of the counter-Biennial artworks, which live on in Manetas's own TLD website: whitneybiennial.com.

.jpg)