The latest in a series of interviews with artists who have a significant body of work that makes use of or responds to network culture and digital technologies. (This post contains nudity.)

Adham Faramawy, Vichy Shower (2014)

I've always been interested in the way material tensions are handled in your work, wherein great haptic spillovers or leaks actively confuse the natural with the synthetic. In Vichy Shower (2014) for example, you employ contrasting material densities. A model drinks mineral water in a parodic demonstration of refreshment; later, we see a pair of hands moisturizing with a digitally enhanced, absurd and all-consuming slime. It's a quick slip from Evian commercial to a kind of Cronenbergian symbiosis. Do you see these natural materials and digital simulations operating in contrast with each other, or in some kind of mutual continuation?

I like how you've phrased this question; it's florid but makes me feel trapped - as if I need air, almost as though there's no exit. Maybe that's my fault in that that's what the videos offer, as if we're in a room filling with viscous material - it's running down the walls and the doors are locked.

I guess I should answer both at different points? Contrast and continuation don't on the surface seem to be mutually exclusive options. In a way, I suppose what's important is that although there are continuations that stretch even beyond the confines of each work, it's often the case that I include aspects or conditions that ensure the simulation fails; it's that failure or friction that's often the most generative aspect.

Maybe the word "simulation" is a problem in the context of my videos so far. In a naive way, although the post-production describes or stems from a description of existing materials, I often see the images firstly as objects and secondly in some sense as propositions. They behave in multiple ways at once, or maybe sequentially. These images describe materiality while also delineating their own material presence and, by extension, that of the viewer.

Maybe that's convoluted or even a little conceited!

I don't think it's conceited. I'd agree that the videos frequently suggest claustrophobic conditions through their depiction of submersion or liquid envelopment, but it'd be too easy to read these factors as simple metaphors for, say, "digital immersion." I guess what I'm hinting at is the way your work seems to smear or blend any simple binaries into more complex relationships. That's where the interest lies for me. Could you tell me something about the process of working with live bodies? What happens when those bodies are subject to some of the processes you employ in post-production?

I like that you've gone "straight there." I totally agree - the idea of setting up a binary between digital and organic could be somewhat simplistic, but yes, I hope setting up those material frictions points towards more complex relationships - material, haptic and optic.

I've found Laura Marks's writing on haptic viewing in her book Touch offers me a few useful tools and textures to help organize my thoughts and delineate my position regarding the production of moving images:

The haptic image indicates figures and then backs away from representing them fully, or, often, moves so close to them that for that reason they are no longer visible. Rather than making the object fully available to view, haptic cinema puts the object into question, calling on the viewer to engage in its imaginative construction. Haptic images pull the viewer close, too close to see properly, and this itself is erotic.

Tellingly, that quote is pulled from a passage on pornographic images, a type of image that I'm often invited to define myself against. This passage not only debunks or at least confuses that reading of my work, but also offers some insight into my use of a shallow depth of field and visible edits to highlight or bring to the fore ideas about the image as object and about the image within an object, seeing the use of monitors as a form of embedding images. This allows me to consider screens as sculptural, or as components of a sculptural assemblage.

I guess in a way it begins to answer your question on what happens to bodies that are subject to processes of post-production. I suppose they become embroiled in a complicated or vacillating subject/object relationship which is dependent on the viewer's approach and the viewing conditions of the work.

I want to ask you about health cultures and cynicism. I don't think you're cynical. In fact, I'd suggest a lot of your work seems to move in the opposite direction, almost euphorically extending the promise of some of these rituals of bodily self-preservation via technological means, and regardless of whether or not you believe them to be effective.

I'm not cynical at all. I'm really prone to falling for the tricks adverts play. I respond, performing for the image in exactly the way I'm expected to. I enter and exit the diagetic space an advert constructs, taking the least resistant route. I then realize I'm being absurd and laugh at my own simplicity.

This almost over-identification with commercial images has so far been a useful critical strategy for me. Sometimes I feel like it's a desperate strategy, because it’s precarious and relies heavily on the viewer's foreknowledge.

It can be a risky strategy as I can become complicit in asserting and perpetuating a strategy of production and dissemination that I'm attempting to question, and this can be troubling.

Under certain conditions, over-identification can be the only option for critical engagement, allowing you to push the operation of an image until its operation is not only visible, but cracks.

Adham Faramawy, Total Flex (2012)

I remember seeing people engage with your film Total Flex during Bloomberg New Contemporaries at the ICA; they were actively moving to the series of exercises performed in the video, being quite creative with their responses. It made me realize that your works make a certain appeal to the body of the observer. Violet Likes Psychic Honey 2(2013), your sculptural video installation, does something similar with its in-built speakers and infectious music. I wondered if you could talk about this appeal - how certain forms of embodiment might provide appropriate grounds for responding to the work.

That's very funny - were people really exercising along with the performer?! I wish I'd seen that.

Priming the viewer's approach to a work is important to me. With the videos and sculptures, this mostly serves to highlight the viewer's own "look," or gaze; trying to call attention to what the viewer brings to the work and not taking a normative gaze for granted.

I consider how the viewer is able to move around a work and which are the optimum points in a room from which to view it. Working with screens and monitor-based videos gives the work a front and a back. Playing with that and with the objecthood of the monitor and the image on it can be fun for me, and it's also an important way of engaging with viewers.

Thinking through physical presence is pretty important to me.

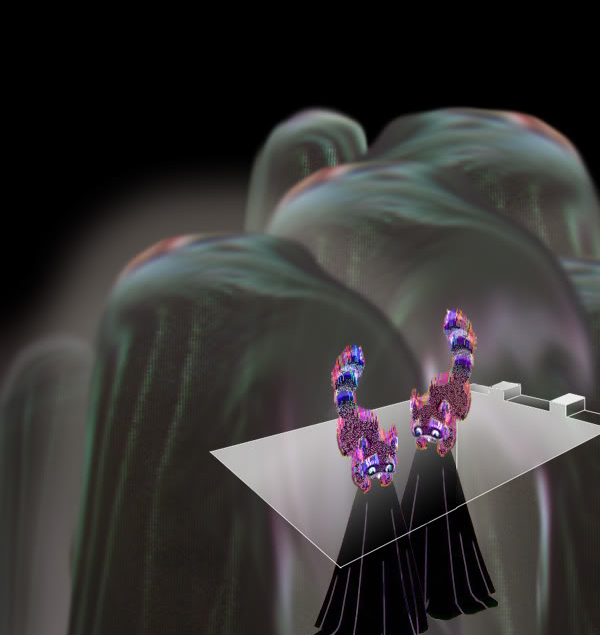

I released my first app earlier this year. It's an augmented reality sculpture called Hi! I'm happy you're here!

The app asks you to register an image then tethers a digital sculptural object to the image on screen. The sculpture morphs over time and has footage embedded in its surface of performers perpetually turning, smiling and waving. I'm in there if you stick with it long enough.

Every aspect of the work calls attention to the viewer/user's physical presence. I've found that the way the piece works encourages certain kinds of motion and engagement, particularly as the physical site of the sculpture is located in the interface between the viewer/user's body and their device. For me, this reading of the work is an extension of the investigation into the linguistic and psychological slippage posited by the binaries set up in the performance videos.

To continue with that interest in the body of the viewer, I'm wondering how the act of dissemination figures in your recent works. For Hyper-Real Flower Blossom (2015) you engineered the 'essence' of a favorite J-Pop YouTube video as a perfume. For me, the work suggested the migration of online content through olfactory diffusion whilst hinting at some kind of symbiotic interface between the video and the wearer of the scent. Similarly, Slimeface Emoji (2015), a downloadable program produced in collaboration with Terry Ryu Kim and launched recently at tank.tv, locates the face of the viewer and obfuscates it with an animated torrent of green slime. Would it be right to say you use media distribution as a kind of playful contamination, testing the thresholds and proximities between bodies and screens?

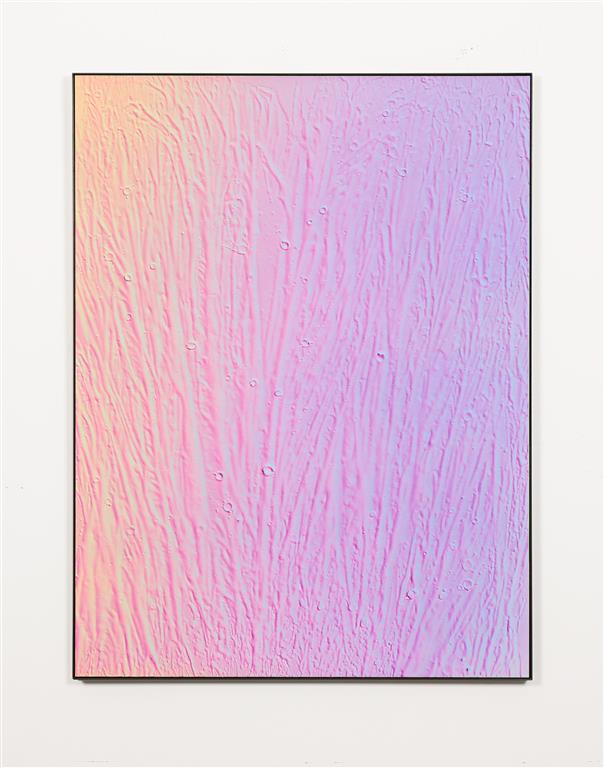

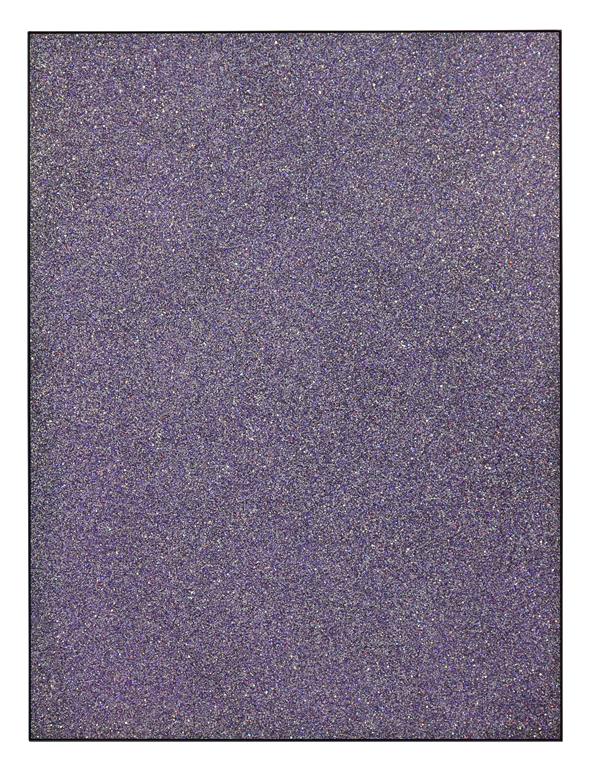

![]()

Adham Faramawy, Hyperreal Flower Blossom (2015)

![]()

Adham Faramawy, Hyperreal Flower Blossom (2015)

Thanks for asking this question in this way, because yes, the viewer's body fascinates me. The Hyperreal Flower Blossom perfume, for me, was a 'translation' of a video of a Vocaloid dancing in a garden. The scent smells like summer. In developing the perfume, I was thinking about the physicality of the Vocaloid; considering how fans produce those bodies and questioning how those bodies are disseminated and displayed. How does the Vocaloid's body occupy space? Vocaloids are an unstable performance of aggregated identities occupying multiple contested sites simultaneously. These ideas of occupation of space are conflated with issues of authorship (re ownership) and their usage as avatars and the relationship that creates with the user's body. This is a complex, precarious form and I find that compelling.

I approached the perfume as a sculpture - a presence without a body. I hadn't fully understood or even considered the implications of how it might transform the user/wearer's body. I don't really know what it does yet, as not enough people have worn it. Get some from Studioleigh.com and you tell me!

I'm really fond of the image of migration from the digital video into scent, but really I've been talking about it in terms of translation and slippage, which I think is slightly different in that it doesn't make the same claim of a transmission.

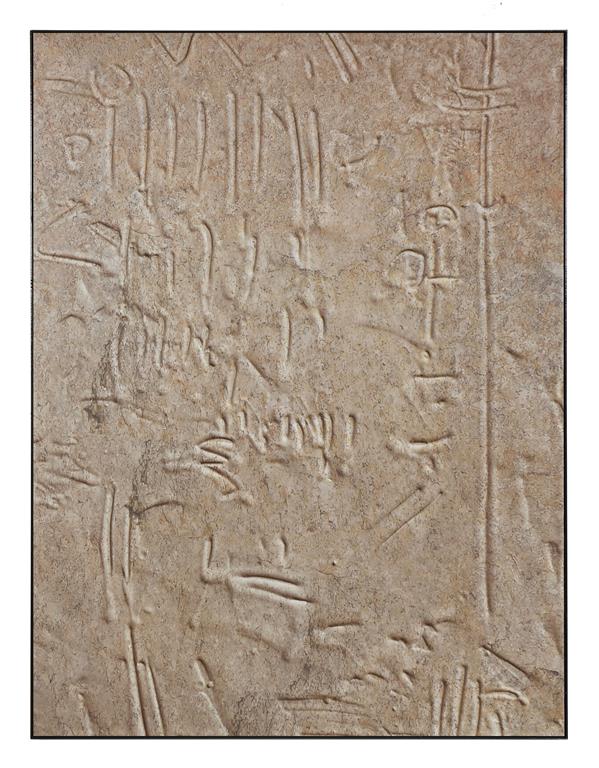

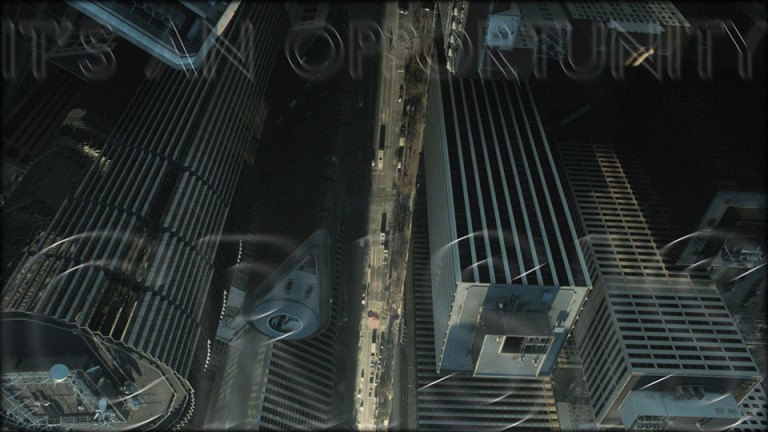

Adham Faramawy, Slimeface Emoji (2015)

This video screen capture demonstrates the facial recognition program I collaborated on with artist Terry Ryu Kim. The soundtrack is a separate track that was included in our sculptural installation of the program at the tank.tv space in London.

Slimeface Emoji has a different relationship to the body. It's a facial recognition program. Terry and I installed it as a sculptural installation with sound at tank.tv.

For me personally, this work came from the research I did with Cecile B. Evans for the Royal Academy symposium event we organized together. It was an attempt to work through the shifts in digital photography, moving away from claims to indexical representation and understanding that other forms of processing are now involved in in the production and dissemination of digital images.

I live really far away from my family and the way I work means I don't see friends in person all that often. I spend a lot of time video chatting and I suppose in a way that both Slimeface Emoji and Hi! I’m happy you’re here! are responses to the ways I need to mediate myself to form and maintain relationships.

I think that for both Terry and I, Slimeface Emoji was an attempt to think through the ways in which computer vision might affect the production, performance and mediation of emotion, so the interface with the viewer's body here was key.

![]()

Adham Faramawy, SlimefaceEmoji! (2015)

Questionnaire:

Age: Oh honey no.

Location: London

How/when did you begin working creatively with technology?

I began experimenting with technology in high school. I recorded performance footage on Hi8 tape and edited on Premiere.

Where did you go to school? What did you study?

I studied art at the Slade (UCL) and then did a post-grad course, also in art, much later at the Royal Academy Schools - both in London.

What do you do for a living or what occupations have you held previously?

I'm a sculptor. My previous jobs were varied and mostly pretty crummy. They range from washing dishes, selling used clothes and assisting artists to office work and light domination. There's more, but you get the idea; in the past I worked a lot of different jobs to make ends meet.

What does your desktop or workspace look like?

I'm fastidiously tidy and only just upgraded the Mac to Yosemite so I haven’t made the space my own yet, but here you go. It's the area around the computer that's really interesting, but I won’t show you that!

![]()

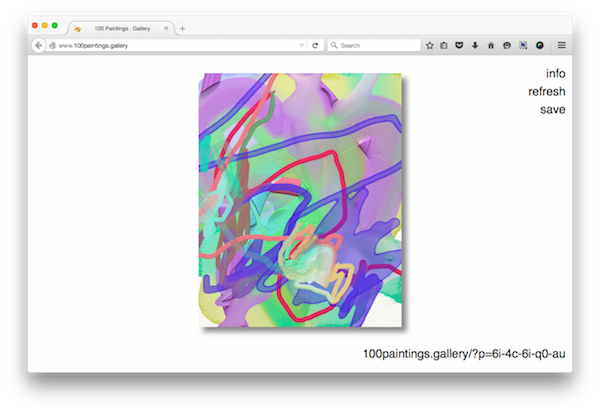

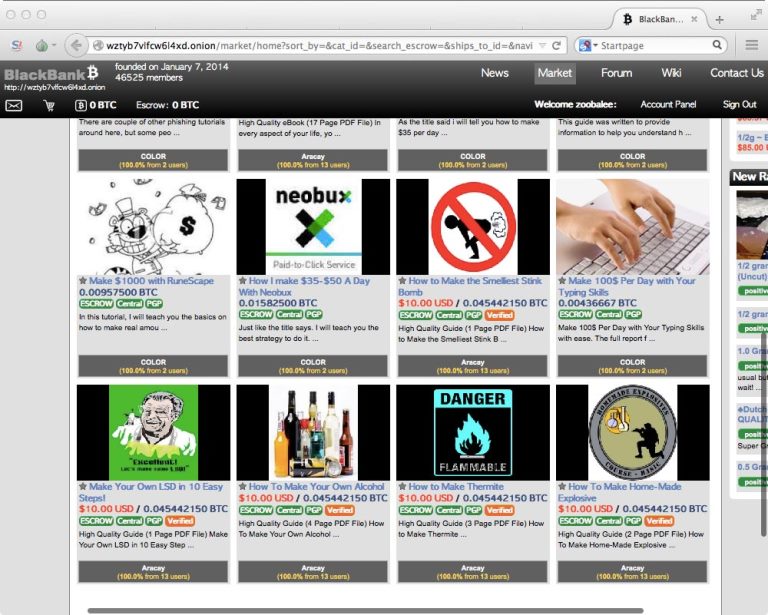

The one that got me. It seemed about as legit as anything else on the deep web.

The one that got me. It seemed about as legit as anything else on the deep web.

.-Screenshot,-detail..jpg)