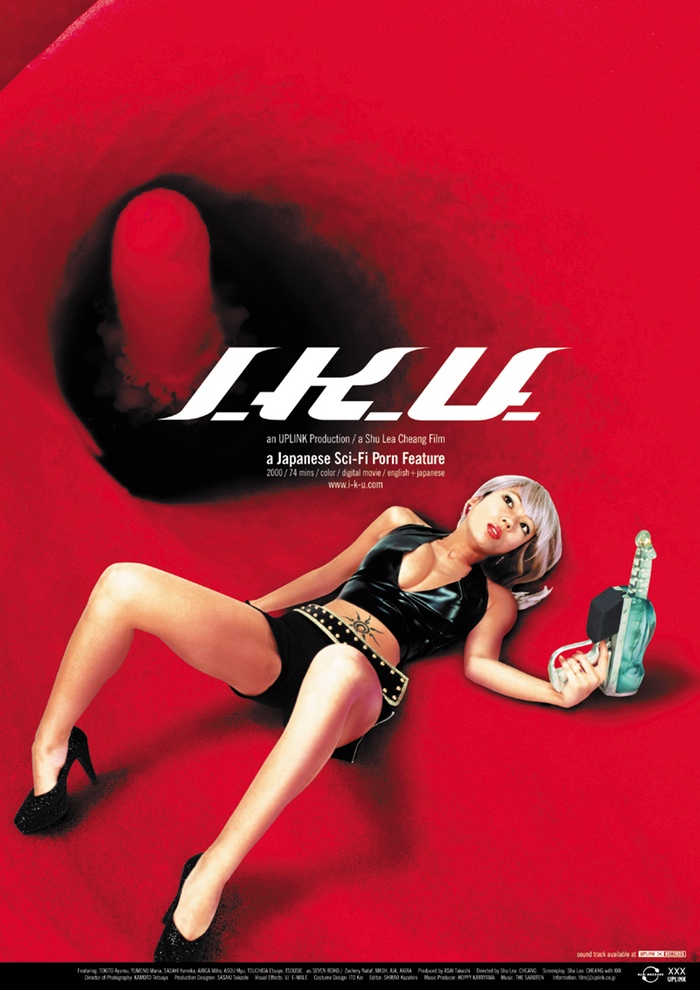

Net art nomad and cyberfeminist Shu Lea Cheang's sci-fi porn film I.K.U. premiered at Sundance Film Festival in 2000. When the film later screened, Cheang conceived a follow-up project for Lars von Trier's Zentropa/Puzzy Power. The company went bankrupt, and FLUIDØ has been on hold ever since, although Cheang was able to make an installation version in 2004.

Now, Cheang has teamed up with producer Juergen Bruening and is running a micro-crowdfunding campaign to to (finally) make FLUIDØ. As part of this effort, she has released these two short clips from I.K.U., which we are sharing along with "The I.K.U. Experience, The Shu-Lea Cheang Phenomenon," originally published in Cinevue, July 2000 and reprinted in New Queer Cinema: The Director’s Cut (2013, Duke University Press).

(Both clips contain nudity, sex, and Y2K-era computer graphics.)

Step right up, ladies and gentlemen, the carnival is about to begin. Come inside, surf the Net, play the video game, dive into the screen, cruise the future, come get fucked, just come, come, come. Bodies are packages made to be opened, minds are penetrable, sensations communicable, orgasms collectable.

Shu Lea Cheang's I.K.U. (subtitled This is not LOVE. This is SEX.) invents a future cybersexual universe, where trained replicants roam the empty spaces of unseen metropolises, hunting willing prey for orgasmic sexual marathons conducted in the service of science. The irresistible replicants are equipped with unicorn-like arms which – presto – turn into dildo machines specifically calibrated to collect and transmit the specifications of orgasms into the centralized, corporatized databases of the future. Meanwhile, the species of the future are wildly indeterminate, gender-blurred or homosex, oversexed or just, well, willing. Shorn of emotion, sex isn't just work. Data has its pleasures, too.

And the audience? Like it or not, we're implicated in it all, swept up by the throbbing techno soundtrack, plunged directly into the action by the animation tunnels that materialize at the onset of arousal. Remember the origin moments of hypertext and interactive video? Every technological invention of the twentieth century has been designed in the service of either pornography or the military. Those early demonstrations of camcorders and interactive video games always featured some version of cyber blow-up dolls gauged to fulfill every fantasy of the male users. Well, I.K.U. democratizes all that. I.K.U. frees the body from gender restrictions, empowers the object of fantasy, and merges the user and the used, the carrier and the carried, into a cyber-satyricon of impulses, stimulants, and gratifications.

I.K.U. is a phenomenon that wants to refuse definition and to a certain extent succeeds in that effort, even as it crosses all categories – geographic, physical, conceptual – with a demented flourish. As much trans-genre as it is trans-gender, I.K.U. also wants to merge video and film into a fresh digital universe large-scale enough to overwhelm the viewer. Narrative, nationality, and production medium are all certainties easily thrown into question. The actors are drawn from the Japanese porn world. They speak broken English. They mutate into shape-shifting manga characters. It's a whole new world, but one that's deliberately low-budget and manageable, shot with digital cameras, edited on Premiere on home computers, then blown up big to 35mm, exaggerated like Godzilla, to conquer its audience. Sure, sometimes it's flat or hokey, one-dimensional or predictable, but more often it surprises and triumphs, the love child of Samuel Delaney and Flaming Ears (1991).

Cheang is the mastermind behind I.K.U. The Taiwanese runaway Shu-Lea Cheang and former scion of the New York art and video scene has now self-reinvented as a "digital drifter." She roams from commission to commission, from Osaka to Amsterdam, London to Tokyo, relaying her transmissions to the internet banks of the present. Until the legendary Japanese producer and distributor Asai Takashi (known for promoting such cutting-edge work as Derek Jarman's last films to Japanese audiences) proposed this sci-fi porn movie for her to direct, Cheang had been deploying her visions straight into cyberspace through her web sites, Brandon (a commemoration commissioned by the Guggenheim Museumi in 1998, predating Boys Don't Cry by a couple of years) and Bowling Alley (commissioned by the Walker Art Center).

It's hard to believe that Cheang started out as one of the Paper Tiger gang, producing low-budget community video with DeeDee Halleck's activist acolytes and flying back to Asia to champion those who died at Tiananmen Square with a five-part camcorder tribute memorial, Will Be Televised (1990). She simultaneously began her move into the art-video world with Color Schemes (1990), an installation which indicated her future interests: it focused on the body, in the form of performance artists, and on playing with viewers' relationship to the work, in this case, scrambling video into laundromat machines and, double trouble, locating those machines in the sacrosanct space of the Whitney Museum. The next project revealed the shape of her future: it was a collaborative installation of sex secrets and video loops, installed in a gallery space transformed into an old-time porn emporium.

Then she was off. Leaving the gallery space, in 1994 Cheang made her first feature film, Fresh Kill, written by Jessica Hagedorn (Dogeaters) and set in a sci-fi New York City where fish are radioactive and the cast multicultural. With the combination of their talents, the film was able to unite conspiracies of world contamination with the investigations of a lesbian couple under threat. It was made in 35mm, a true change of gears for the low-budget artiste, yet it embraced the worlds of hacking and ecoconspiracy so totally that it had a hard time finding traditional distribution even in the heyday of the NQC. Not one to be typecast, Cheang also tossed off a pair of lesbian porn tapes, Sex Fish (1993) and Sex Bowl (1994), in this period that showed what a flair she had for sex work in the idiom of cutting-edge video.

Then she was off again, this time into cyberspace. She gave up her New York digs and became a global wanderer, a "floating digital agent," jacking into power supplies around the world and reachable only through web sites and e-mail. Did she really exist? Happily, yes. When spied in 2000 at Sundance and at Pitzer College, where we shared a residency, Cheang looked like one of her characters: her head shaved except for a sprig of hair that Jessica Hagedorn's daughter had dubbed an "island," swaddled in a wraparound butcher's apron made of a material that managed to suggest a cross between black leather and latex. Perched on platform shoes that upped her stature, fusing fashion and fetish, she easily fulfilled her self-appointed role as avatar. Never mind that, characteristically contrarian, she preferred to ignore all this synthetic construction and talk about the future as she saw it: organic farming, her new passion.

Cheang defines I.K.U. precisely: it's a porn film that takes up where Blade Runner (1982) left off. The elevator door that closed now re-opens. A new corporation has taken over. The I.K.U. characters have names, identities, and missions, but I don't think the story is the point, however carefully calibrated it may be. Narrative, which once was the weak spot in Cheang's work, has become its strength. Or, rather, it is the very absence of narrative that has now supercharged her work, suffusing its every choice. Cheang's mix of sensation and suggestion is perfectly suited to the post-hypertext world of post-verbal storytelling. What's most intriguing about I.K.U. is its daring disposal of older forms and its unabashed effort to pioneer a visual text in which pornography and science fiction, film and video and computer, matinee and late-night, gallery and porn arcade, all merge into a single movie experience.

As collaborative as ever, Cheang involved a range of Tokyo figures from the worlds of club culture, night life, and adult movies. Production designer Sasaki Takashi and VJ E-Male work the club scene, creating visual effects. The character of replicant Reiko is played by Tokitoh Ayumu, an erotic actress from the world of satellite television. Another characer, Dizzy, is played by Zachery Nataf, who's identified in the production notes as an F2M transsexual (transman, in newer parlance) and founder of the Transgender Film Festival in London. Other parts were played by humans drawn from the ranks of magazine models, strippers, porn stars, even a "rope artist."

I suspect that none of this is remotely fringe for Cheang. Rather these are the personae of a future that's just now coming into view; she has simply given them a context. In the process, she's given her audience a challenge. A whirlpool (cesspool?) of ideas, I.K.U. has usefully provoked meditations on the nature of sex, narrative, and representation that we'd be well advised to put to further use, here and now, on the cusp of the alleged media future.

Naturally, not everyone has been ready for what Cheang had to offer, even in the Y2K era in Park City, Utah. At its world premiere at Sundance, despite the word "porn" in its catalogue description that ought to have set audience expectations appropriately, I.K.U. managed to scandalize a midnight crowd that's usually self-congratulatory and proud of withstanding, if not embracing, anything thrown at it by the most fiendish of minds. But clearly that brand of hipness has its limits.

In place of self-satisfaction, the I.K.U. experience sent folks scurrying for the exits whenever the action got explicit (40 percent fled, according to Cheang). Shu-Lea Cheang was taken aback, troubled: she thought Sundance was more sophisticated. I, on the other hand, was delighted: in the post-NQC days of posed tolerance, how reassuring it was to see that people still could be shocked by something.