Presented as part of Net Art Anthology, Rhizome's ongoing online exhibition that charts a history of net art through one hundred works, How Do You See the Disappeared? A Warm Database (2004) was the beginning of a larger collaborative project by Chitra Ganesh and Mariam Ghani called Index of the Disappeared. Ongoing since 2004, the Index takes the form of an archive that “traces the ways in which censorship and data blackouts are part of a broader shift to secrecy that allows for disappearances, deportations, renditions and detentions on an unprecedented scale.”

With How Do You See the Disappeared? A Warm Database, a 2004 commission for the digital art organization Turbulence.org, Ghani put forth a concept of “warm data”–affective information that could not be used by the state. In particular, Ghani was responding to the data-driven practices adopted by the state in the wake of 9/11, particularly around identifying thousands of Arab and South Asian Muslim men as part of "special interest" groups, rounding them up, and holding them indefinitely, as well as forcing noncitizens from selected countries (most of them predominantly Muslim) to appear for questioning by immigration officials as part of the t"special registration" policy.

The web-based project featured a hypertext essay, watercolor portraits of the Disappeared, a questionnaire, and visualizations of the answers, as well as accounts of activist efforts and links to political resources.

Ghani will discuss this work on Friday, November 3 at Rhizome's panel discussion Net Art Anthology: Distribution and Disappearance After 9/11. Tickets are available here.

Michael Connor: How did you begin working together?

Chitra Ganesh: Mariam and I met in the late 1990s when she was working at Exit Art, which hosted a few events put on by the South Asian Women’s Creative Collective. I'm a lifelong New Yorker - I was here throughout September 11th, and Mariam was also here. Navigating from one place to another was difficult. Flyers of missing and disappeared people, mainly victims from the September 11 tragedy, were plastered all over the city's walls, architecture, public transportation.

For me, this invoked the absence of another simultaneous and very upsetting narrative, which was the targeting and rounding up of immigrant populations, specifically those of Arab and South Asian and Muslim descent. Those were, of course, people in our community, and friends of friends, known people. That was one of the things that I was thinking about in terms of a kind of overlooked,concurrent narrative to the narrative of disappearance or death and loss, that was at the forefront of how people were thinking at that moment immediately afterwards about 9/11.

Both of us [were] thinking about how to look at a way to think about representing these subjects, these stories, these subjectivities with a kind of a visual form that rubbed against the grain of the kind of demographic data gathering and subsequent erasures of the people who were being targeted.

Mariam Ghani: When I got the Turbulence commission to make Have You Seen The Disappeared? A Warm Database, it was basically right at the beginning of my collaboration with Chitra - the collaboration that became Index of The Disappeared.

That came about because we had both been separately working on these issues through our involvement with immigrant rights activism. Then we had also been thinking about them through our own individual work. We'd known each other for quite a long time. We were friends. We also had this kind of funny thing where we were always in large group shows right next to each other and on facing pages of the catalogs because we're alphabetically right next to each other.

And then finally somebody just put us in a two person show. So we just started collaborating. That was a show during the Republican National Convention in New York, at White Box.

CG: Both of us were asked to present a work that responded to the 2004 Republican National Convention. To think about ideas that have maybe been marginalized within the electoral discourse and politics of the time.

We both individually thought about detention and deportation as one of these areas of discourse that was just not appearing within any set of debates or political platforms in the way that we thought that it should.

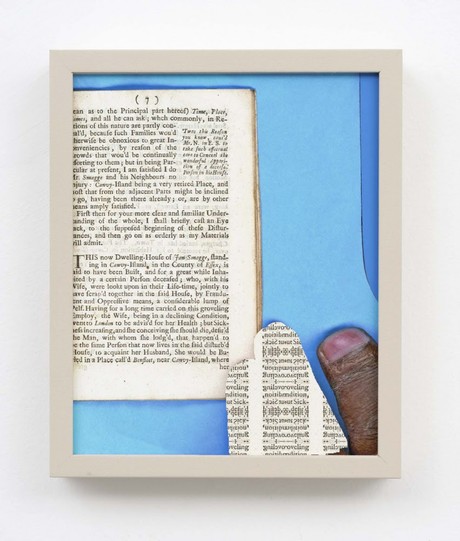

Mariam Ghani and Chitra Ganesh, How Do You See the Disappeared? A Warm Database (2004).

MG: It was a whole series of two-person shows of artists responding to issues that weren't being covered in the political debate leading up to that election. We chose to look at this issue of the post-9/11 detentions and deportations that were ravaging immigrant communities in New York and across the United States –all these disappearances in these immigrant communities that we were a part of.

We started collaborating from that point. I had made a video for the show called How Do You See The Disappeared? So the 'how' section of How Do You See The Disappeared? A Warm database was basically an adaptation of the video, constructed from the same sources.

CG: My part of it featured a window installation of overlapping watercolors, images of people who had been indefinitely detained, deported, neglected and disappeared in the post 9/11 processes that targeted immigrant and dissenting/activist communities. The installation referenced that form of the missing persons flyer that was proliferating in public spaces in downtown Manhattan, in the months following September 11. I wanted to use that form to think about how there were these parallel narratives of human disappearance and legal erasure that were emerging from the racial profiling and indefinite detention.

I thought about, for example, the medium of watercolor as a different way of visualizing these subjects who otherwise, at that point, were being presented as tiny, degraded, pixelated black and white photos in the newspaper. Or not presented at all, like there wasn't even a sense of who these people were - they were question marks that were part of a larger abstract issue that few people were thinking about.

Mariam Ghani and Chitra Ganesh, How Do You See the Disappeared? A Warm Database (2004).

Another thing that I remembered is just also from growing up in New York City and riding the subway by myself from when I was 10, I remember also the way that the ...wanted sketches of “suspects” would be in pencil, and... the features always struck me as being so similar.

It was always, "Five foot 10, light skin, black, or Hispanic man, with a little bit of a mustache or not." And just even the lack of specificity of the visual language around the wanted or the hunted I thought was really creepy, and so for me, working with something like watercolor and really thinking much more closely about skin, and the bodily material qualities of human presence was important.

The idea of using watercolor as a medium that's historically associated with sort of the everyday, with Sunday painting, landscape, leisure, enjoyment, to represent a kind of practice of erasure and faces and bodies of people who had experienced certain kinds of brutality or injustice, and whose experiences are often those individuated experiences, and the nuance and texture of those experiences and those lives are often dissolved within larger dialogues around terror.

This idea of trying to capture the nuance, the texture, the subtlety, the affective dimensions and the sort of psychic ruptures that exceed an official way of categorizing a subject, was something that underpinned all of the work, including the Turbulence project. To think about this idea that Mariam had generated, of warm data, through the essay that she wrote. To think about what kinds of information, what kinds of phrases or poetic fragments or pieces of information people provide that would exceed and kind of give a greater depth of dignity and humanity to these subjectivities.

MC: It's interesting that what is coming across is a sense of a failure of representation of the disappeared––using warm data to counter the way they were depicted in lo-res, or not at all.

CG: But also just very much caricatured and misidentified and mistaken, you know? For example, you will have, I don't know, a nomenclature like Muhammad Saleh Abdul Hussein, and they will pick up some person who they think has some version of this name, but they've picked up the totally wrong person.

That misapprehension, misidentity, all of these things that I think actually not only predicted the culture of racial profiling and of sort of FBI targeting of Muslim student associations all over the city, but also drew upon what was already happening in the carceral politics of the US with the failure of witness identification, with unjustly convicting people, and so on and so forth. It's not like I felt or we felt like this was something brand new that was happening after September 11th. It did sort of signal a mounting creep of this kind of behavior.

MG: Before everything that happened in the wake of 9/11, I think artists hadn't really started to think about the politics of databases in the way that we started to think about them afterwards, especially about two-three years afterwards when I was starting to work on the Warn Database.

[That's] when we were really starting to understand how processes like special interest detention and special registration were really very much data-driven. We didn't really start to understand that until some of the gag orders were lifted two years later.

Once that information started to emerge, for me and I think other artists also at the time, we began to look differently at the databases with which we had been working with as underpinnings of our own projects, in light of the official and commercial uses that were being made of databases and data.

I remember seeing this Builder's Association performance at BAM... They ran the credit card information of everyone who had bought a ticket to their performance, then used that to profile them, and actually wrapped that profile information into the performance. It was, I think, one of the first moments for a lot of the people in that audience where they realized that they actually had data bodies, that there were these shadow bodies of data that followed them through the world and that were surprisingly accessible to other people.

That's what really became apparent around this time: your data body was incredibly vulnerable. Things that happen to your data body actually could affect your real body.

The Warm Data questionnaire came out of three or four things. One was a series of conversations I had with a friend who had debriefed some of the special interest detainees before they were deported, and had found out what kind of questions they had been asked during interrogation. They had been asked the same questions over and over and over again.

Mariam Ghani and Chitra Ganesh, How Do You See the Disappeared? A Warm Database (2004).

Another thing that was that Chitra and I were both going on visits with a group out of the Riverside Church that was visiting asylum seekers who were in the Wackenhut Detention Center in Queens, which at the time was run by CCA, the Corrections Corporation of America. It's one of the two biggest private prison companies in the United States.

We were visiting asylum seekers who were awaiting adjudication of their applications in this prison, and talking to them about what questions they would want to be asked––what conversations they were not having while they were waiting for one, two, three years in prison for their status to be determined.

Then it was looking at the questions that people were asked when they went in for special registration in 2003.

It was basically trying to design something that was the opposite of these kind of interrogation and special registration questions, and instead was something more like what the asylum seekers were asking me to ask them.

The fourth factor was the desire that was constantly expressed by immigrant rights advocates, which was, “How do we put a face on the issue"?

It was a really thorny problem in that context because you want to personalize the problem or you want to scale this big abstract discussion or debate down to individual and specific terms. But in that particular context, there were so many people who were truly afraid of losing their legal immigration status or revealing their status as illegal immigrants if they came forward and told their individual stories.

Others were part of communities where it really carried a stigma to be out of status. So many people didn't want to tell their individual stories and have them actually attached to their real names and real faces. That problem in immigrant rights advocacy led me to ask whether it would be possible to create a portrait of someone that would be specific and individual but at the same time, not identify them to anyone except maybe, maybe their closest friends and family. The idea was to create a data portrait that wouldn't be a data body..

CG: For me, it was also about painting and the layering of individual strokes to create these portraits that emerge in the process of looking and thinking about these subjects, and also thinking about the relationship between figuration and the other. Thinking about how figuration and conjuring something very specific of a figure and how the audience looks at it and confronts their own closeness and indifference to the human form.

We're both interested in connecting histories that might not necessarily be put together in the same frame, or thinking about a visual language that would better explore or expose those histories. Both of us are also interested the intersections of language and image, of text and image. Working with and within text and certain textual forms to create new meanings or new positions for the audience to enter a work.

These were some of the things that we were thinking about in terms of what kinds of evocative memories would fall between the cracks of an official dialogue, that might be able to puncture the distance and between the way the conversation was happening and the larger public debate around that post 9/11, and the actual lives and people being affected that were never really seen.

Combining letter writing, note taking, painting, these kind of very analog forms within this platform of creating a digital archive, or any kind of ... just creating an archive around these absences and erasures.

MG: The challenge I set myself was: Could I create a questionnaire, which no two people would ever answer in the same way?

The sets of answers are never identical, but could never [be used to] identify someone. It does create this kind of specific individuality, and at the same time, it's so far from being cold, hard fact or anything that can be used as evidence or held against you in a court of law or really even tied to you in the same way that normal data points can be tied to someone.

It's a very fuzzy sort of data. That was the idea. Warm data as opposed to cold data.

I was, in many ways, defining warm data by what it wasn't - in opposition to other kinds of data and other practices of data collection. So one of the criteria was that it had to be collected by invitation, not interrogation. Another criteria was that people had to be free to not answer any of the questions. People also had to be able to answer anonymously. There had to be anonymizing practices in place to separate the data from the people who answered the questions. There were also considerations around never constructing a set of data points that could be used as evidence.

When you think about warm data and those sort of questions, you're asking people to expose very personal information. So I was trying to do it in a way that wouldn't make them personally vulnerable. That was the trick of it, in a sense. A very delicate balance in the construction of the questions between specificity and anonymity.

A good example of a question on the questionnaire that really functions in this way is, "Describe an offhand remark that someone once made to you that you've never been able to forget." It's very rare that five people in a room will answer this question in the same way. Even if it's the same phrase, they won't remember it for the same reason. Andat the same time, it’s not a data point from which anyone would ever be able to identify you unless they are incredibly intimate with you.That's the kind of story you tell very few people in your life.

Mariam Ghani and Chitra Ganesh, How Do You See the Disappeared? A Warm Database (2004).

CG: We gathered the material in a number of different ways. We tend to gather the material by talking to people initially, of course, talking to lawyers and activists involved, talking to people working on detention center meetings. And also the material was also gathered by looking closely at transcripts and testimony, and noticing certain patterns that would be available or emerge over and over again. That felt very evocative.

MG:The first few questionnaires, which are the ones that were done as a prototype in the website when it went live, those were actually done with me asking the questions in person to people. Then a number of questionnaires were submitted through the website during its first years online. Then we started actually putting the questionnaire in installations of the Index when the archives were on view. So we have a lot of physical questionnaires that have been filled out, and we've never exactly figured out what to do with them. But we have them.

Those are, of course, completely anonymous. It's just people who were in the installation at some point in the months it was on view in some space and filled out the questionnaire.

You know, as with any kind of participatory element, there's always some small percentage of people who fill it out like a joke. But there's a surprising number of people who fill it out very seriously and reveal a lot of very intimate things through this questionnaire. It's kind of astonishing, the variety of experiences that are revealed through this set of questions. It was surprising to me, reading one set of responses after another after another. It really is like a miniature portrait of somebody that at the same time, doesn't give you any of the usual data points that describe someone. It doesn't tell you their gender or their race or their sexuality.

MC: Within this process, were there particular individuals who really came across and stick with you?

MG: It's been a long time since I looked at the answers. One of the initial ones that we actually did for the website was an asylum seeker who I was visiting in the detention center. His set of answers, I thought, were really beautiful.

"Josiah Emmanuel at the Wackenhut Detention Center in Queens." He withdrew his asylum application and went back to Nigeria right after he did this. Right after he filled out this questionnaire.

He was someone I had been visiting for, if I recall correctly, almost a year at that point. He just couldn't take the detention center anymore.There were twelve beds to a room. They had the televisions going constantly and the lights only went out four hours a day. People had a lot of trouble sleeping, and it was very difficult for them to be alone with their own thoughts without some other stimulus like other people, other sound, other images. People were treated like they were in prison, not like they were seeking asylum.

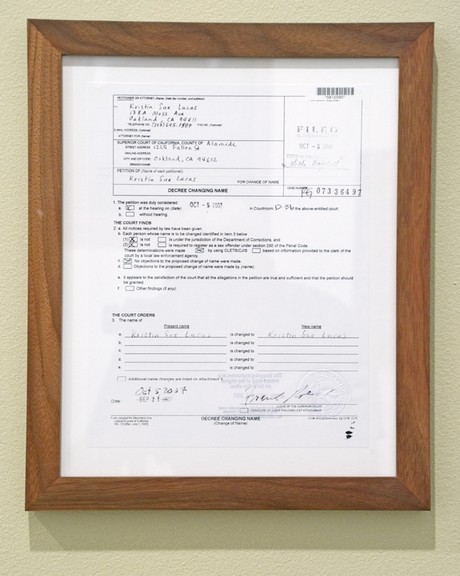

Later I made a series of projects called Points of Proof, based on a single question from the warm data questionnaire. Particular questions from the questionnaire did have that potential tobe expanded out into their own little universes. I only ever did it with the one question: If someone questioned your right to be American, what proof would you offer?

The longer-term impact of the project has been, I think, in introducing this particular notion of warm data, which in the decade-plus following the Warm Database and my Viralnet essay “Divining the Question: An Unscientific Methodology for the Collection of Warm Data” has been taken up and expanded by others in some really beautiful and unexpected ways - especially in queer and diasporic theory dealing with affective archives and the sensorial life of empire. For us of course it was the beginning of what became a long, wide-ranging and fruitful collaboration on Index of the Disappeared.

Introduction to an Index, Chitra Ganesh and Mariam Ghani

MC: Is Index of the Disappeared still an ongoing project? Is it something you can just return to periodically? And where is this process of disappearance in present moment?

CG: I feel like the project is ongoing. We're currently working on a reader, which is something of a larger text publication with invited contributions and artist pages and also our own material, but that sort of is able to take a more encyclopedic view of the last fourteen years of the project.

We're in this really bizarre era where the terms of the conversation have changed completely. For the longest time, people just felt like, “oh if we just had evidence of x, y, and z…” Somehow presenting that evidence, or being confronted with it, would actually create a more policy-based shift, or a larger kind of shifts in government.

But now you see that no matter how much evidence there is, there is still this other kind of friction. For example, if you look at the state sponsored assassination of black citizens enacted by the police. Or you see the Muslim people in India being lynched for selling beef, which is something they've been doing for quite a long time. You see all of these things recorded and put into the public domain. We're just in a different place around what evidence means, and how it can function.

As far as I see it,it’s definitely not the moment where visual evidence will not be a corrective or hopeful locus of change, that one once thought.

And even in the time that the project has developed, communication and technologies have changed entirely. But the archive still is in that kind of position of having to think about carefully what's said and what isn't said. Thinking about not just what's there but what's absent and how that impacts the archive. Not just outside the archive, but what in the archive.

Another aspect that's still very much present in relation to our project, is this idea of the archive being something that doesn't necessarily chart a teleological or linear way forward, but is really much more of a constellation and much more about connecting the dots.

And I think that part of the project's approach to the archive is something that is work that continues to need to be done. Just in terms of expressively positing a different kind of way of thinking about how information systems are organized. To make some of those connections within the archive, and also question its stability.

.jpg)

I-BE AREA

I-BE AREA _big.png)

.png)

Image via

Image via