This interview is taken from What's to be Done?, a publication produced by Rhizome and Wieden + Kennedy New York for the 10th edition of Seven on Seven. The magazine was edited by Rhizome special projects editor Nora Khan, and designed by Richard Turley, global creative director at Wieden + Kennedy. With a donation of $30 or more to Rhizome, we'll send you a copy of the full publication, which features texts and interviews by Paul Chan, Fred Turner, Claire L Evans, and more.

We watched Tracy Chou's collaboration with Claire Evans with admiration: bots with randomized genders and voices played out a tense, tight drama about a plausible Silicon Valley office. Chou, a software engineer, entrepreneur, and tireless diversity advocate, has a clear and intuitive understanding of programming and systems, which she passionately applies to engineering of equitable frameworks to counterbalance gender discrimination and bias.

We thought Chou's focus on systemic institutional issues would intersect will with Kate Ray's interests. Ray, a programmer, engineer, and journalist, deploys her accessible, allow amateurs to replicate media giant website designs in an hour, and address gender violence and sexual harassment through both low-tech mediums and open-source design processes.

On a Saturday at NEW INC., the discussed their mutual interest in systems and representation, Silicon Valley's blind spots, neoliberalism, what an ethical design of systems might look like, and the present and future of women in tech.

Nora Khan, Rhizome: I’d like to start with both of your collaborations – Kate, yours with Holly Herndon and Tracy, yours with Claire Evans. What did you learn from the experience?

Kate Ray:I had a really good collaboration. I do most of my projects solo, aside from work, which has to be collaborative. I remember being really nervous ahead of time that I would have to work on something with somebody, especially in a high-pressure situation. I was really happy with how our conversations went, and that we were really building on each other. I don't know if I've worked so well with someone in that intense way. Maybe it just shows that you're really good at picking; I think you guys paired us really well.

The project was SPYKE, which was like an old chat app where you had to enable your video camera in order to start talking with somebody. But here, you wouldn't see a video anywhere. You would just see the chat box. You could take a picture of them at any point along the way, and they wouldn't know that it was happening. You'd sort of be spying on them even though you've authorized them to do it. I have been thinking about this a lot this week with all the Facebook revelations. I feel like we were sort of just exploring stuff, and it was really abstract. In the conversation we got into some of the ideas around surveillance; what if you give someone permission to watch, but it still doesn't feel like they're actually surveilling you? The project feels much more concrete when you think about what Facebook has been doing. It started out in this really abstract and emotional place, but certain aspects of it feel more relevant right now.

Tracy Chou:It was great, my project with Claire. So, Claire is a very multi-talented person. She is a singer and songwriter, and a writer. She recently released a book too [Broad Band: The Untold History of the Women of the Internet.] I had a little bit of anxiety because I just didn't know what we were supposed to do. I think in contrast with you, Kate, most of my projects are in collaboration. I've mostly worked on teams with other people. The collaboration part wasn't scary to me. In most cases, I have relatively well-defined output goals: I'm trying to build this project, or product. I'm the engineer on the project, and there is a product manager and designer, and it is very clear. In this case, the goal was just to produce something cool. We didn't know each other before, so there was a bit of mutual discovery around the different perspectives, skills, and experiences that we wanted to bring.

Pretty quickly, we found some common ground around gender issues relating to technology. I thought because she was a singer, she'd want to do some musical. She said, "No, I'm actually in a band with my partner, and I don't feel whole making music without him." That's interesting. I'm not artistic at all. I guess that was the point, pairing a technologist and an artist. She asked, "How about we do a play? And I will write the play." I don't know anybody's who's ever written a play. It's just so far out of my domain. Then she started a Google Doc, and just started writing. I was watching her type out the play in real time. It was kind of amazing. I had never seen that happen before. I had never really spent time with writers in real time.

NK:It seems like it had been labored over much longer. Watching that construction of artificial language was fascinating. Artificial languages demand care and creativity and thought, because the bot- writer thinks long and hard on how a person will respond, on what will make a person feel warm or responsive.

TC: Claire just kind of knocked it out. I was watching her compose it, and then I wrote the Python script to read it out loud in all different permutations. I was amazed by her writing process. Similarly, she watched me do the technical side and was like, "Wow, how did you make the computer read these things aloud in different voices?" She was writing a play script, and I was writing a Python script, and they came together so well. That was cool, to be able to jam together. I started playing with different things, like how long we should pause in between the different characters, how we should slow it down for the robotic voice. She got to test the voice out as well, adding different punctuation based on how the voice would read it differently.

NK: You both talk about or work on redesigning systems through your work, to either reveal or address the unseen. Kate, you have your map where people can mark places they have cried throughout New York and elsewhere. Spyke gives us intimate glimpses of people alone. Bots, maps, language trees. How do you imagine systems revealing the hidden, whether they're biases, microaggressions, or, say, emotional nuances flattened out by sterile, impersonal environments, like work?

TC: The first thing that comes to mind is a discussion I was having with one of my professors from school, who's leading in the AI field. We were talking about this issue of bias in models built from data that is biased. One very promising thing is once you've identified that bias, you can, in some cases, remove it. There was one study that's been floating around about gendered language. If you are training your models over a corpus of general human language data, they'll often pick up gender affiliations between male and doctor, female and nurse. You could say in that case, that the model's working really well. It picks up exactly what it was being fed, which is, unfortunately, biased data. But then we can actually choose to go zero out those biases if we think that there shouldn't be a male correlation to doctor and a female, to nurse.

What's promising there is once we've identified the bias, we can remove it, which is not the same with humans. If you talk to a human, and identify that they have some sort of bias, whether it's sexist or racist or some other form – it's very hard to behave in a way that's not biased. With the machine learning model – with the right types of models – you can just go and manually zero out those parameters. It's not the case for all models. There's a lot of work being done right now in the AI field, especially around deep learning, to make the models interpretable. So, there's been a little bit of a trade-off, where the models that are easiest to interpret are often not the most performant ones. You could imagine, pretty easily, a decision tree. What it is doing is it is walking down a tree of yes, no. Does it cross a threshold or not? You just go down the tree. It is pretty easy to understand how the model made a decision.

But those models don't perform as well as the black box neural networks. There are a bunch of researchers working now on how to understand what those black boxes are doing inside. So, if a decision is made that is not ideal, we can go in and examine why it happened. A lot of times these systems are just training on things you don't understand. When you look at the data, you have some intuition for the domain. You can figure out what it is. In other cases, it's about finding some smart thing in the data. We can't figure out what it is when we're just presented with all of the numbers that are the parameters.

NK: Playing devil's advocate, one might say that this is a road to creating politically correct AI and “politically correct systems.” Meaning, we’re creating data that is equitable when people themselves are not. The flip side of that is, what would a trans-feminist data set look like? An anti-capitalist dataset?

TC: I think it's hard to say what something should be. You can say, let's devise the system, but what does a non-biased system look like, and what does it mean to create an optimal system? There's still a lot of human editorialization, and as you pointed out, what we accept to be good also changes very quickly. Our norms change very quickly. Do we also update all of the models that we're building to map to the new versions of what is correct?

NK:And our positions change based on emotional context, too. Kate, what I really appreciate about SPYKE, is the unearned intimacy with these people front of their computer scrolling through their feeds. It is voyeuristic, seeing these private moments, faces morphing from happy to glum within minutes. Could you talk about your projects as they frame our relationships with technology as extremely human and emotional?

KR: I would say my projects are all very intentionally anti-technology. In general, they have required humans to do human work to make them even a little bit interesting. The only time I have thought of using machine learning was if I could use it in an artistic way, as opposed to creating utility out of it.

A project that I made last year, for Ingrid [Burrington]’s conference about science and speculative fiction, was a really simple bookshelf app. You could use it to make a set of book mixtapes that you could like. You could just name a bunch of books and put them together into a list, and give the list a weird name. Being the opposite of Goodreads is what I was going for. There's no action that you're doing that is creating data. The app is just you, the person deciding what data you want it to make, and then creating it. The same goes for the Cry in Public app. There is nothing interesting there, except for the human's personality being funneled in a very particular way.

I would rather work on projects that use technology but are kind of anti-technology in ethic. I want to investigate the limits around what technology is doing to your data, and find some interesting things going on there. I'm not even using it to make something happen.

NK:It’s a mode of turning people's attention to alternative possibility. This is why your Scroll Kit was used so heavily. There’s a nice divergence here between creating shifts in perception through software experiments, and creating shifts in perception by revealing institutional inadequacy. Do you both think about the tension between experimentation and professionalization within tech, especially as you work with activists now, some of whom worked in Silicon Valley and decide to leave? What types of communities are you able to build within institutions versus outside?

KR:I've struggled a lot with this in the last year, because I used to be immersed in tech. I see a lot of solutions there. But in the last year, I've not wanted to work in it at all. I ask myself, okay, what do I do? Work-wise, I've found a job that honestly isn't a tech company; I work at Pilot Works, which helps people start food businesses. We are renting kitchen spaces and getting people to cook, enabling that communing with a bunch of technology. I do all of my side projects just for myself, with no money coming from anyone. That way I can keep it the way that I want it to be.

NK: Is there value in creating your own communities versus working alone? How has that changed for the both of you throughout your careers?

KR:Well, I've been thinking a lot about gender stuff with the #MeToo movement. Once that came through, I started trying to work on something to address it. Even there, I got in over my head. I said, I don't think I should be making anything. So I started volunteering for an assault hotline. That is the lowest tech. It's an ASP app that breaks all the time when you're trying to train. It's actually interesting, because it's like a really pure form of humanness coming through this not-great chat app; sometimes you feel like you're behaving like a robot, because you have all these scripts to say. But the only thing that you are providing is your human empathy and human presence, your being there. I like how this is the lowest tech, that is enabling some humanness to come through.

I don't know if this will be my solution forever, but I feel like I am backed away from a lot of problems that I don't know what to do about anymore.

TC: Yeah. The tension between working with or within problematic institutions, versus outside of them for a change, is one I see all the time. I personally felt to be more effective to be within institutions or on the inside, because then you understand how those systems work. You know what the leverage points are, and who the right people are to go to. In the end, these are all the people, so you just need to have that human map. From the outside, it's hard to know what drives people to do things or not do them. Obviously, working from within the system has its challenges because then you feel like you are complicit with the bad system, and potentially compromising your values. There is something nice about tracking the totally ideologically pure route, but often, it's not very practical. When you're not following what you believe to be ideologically pure, it can be hard to defend the line in the sand that you've drawn, whatever it is.

I've seen both sides of it. Not intentionally, because I wanted to step out of a major institution, but because I've worked in Pinterest for a number of years and wanted to go on to do other things. I'm no longer at a big-ish tech company, but I've still been operating within the system. I've been working on a few different startup projects. I'm on my third startup idea project since I left Pinterest.

Startups will often participate in incubators as they grow. We had a lot of heated discussions about which programs it was okay for me to participate in, because many have not always had the best record on diversity and inclusion. I still thought it was valuable to go and see these programs from the inside. I have many friends who have gone through these programs and work for them. However being in a cohort was very eye opening. It enabled me to give a lot of concrete feedback. I have no idea if they're going to take my feedback, but there's a lot of daily reminder elements that would only be caught by somebody going through the system.

Take one minor example. When you submit an application, you usually have to indicate your areas of expertise. You check off areas like artificial intelligence, backend engineering, marketing, sales, all these different things. Diversity and inclusion is never one of those things. It's like, wow, no one has thought this would be an important area of expertise. And I don’t think this issue is critical, but it's just one symptom of a greater problem.

Another time in a similar context, a presenter spoke about how people view the valuations of their companies like they do the size of their manhood. I was looking around the room, thinking, did nobody else hear that? Why is nobody else upset? There's like hundreds of people, but no one else seems to be upset. There are always a lot of little things. Accumulated, these instances are not intentionally trying to push someone like me out or anything.

One of the other takeaways for me was that, when you’re a startup, most of everything is about growing your company, so even the female founders or under-represented minority founders for the most part are not thinking about the microaggressions they experience, or how to make spaces and places more equitable. They are just trying to focus on growing their companies. I pay a little bit more attention to these things, because I worked so much in diversity and inclusion. I am naturally primed to pick up these little cues. But I acknowledge that the bulk of people's attention is not going towards these issues.

NK:You have spoken about the idea of diversity as a kind of “lowering of the bar,” which is of course a really insidious kind of racist thinking. When you logically deconstruct this language and thinking, there’s a kind of beauty to that. So when person A says, person B was just brought in because of inclusion, you can eye their assumptions. They assumed the working plane was flat to begin with. And what person A is really saying is that, person B, in their mind, doesn’t really have the capacity to do the job. Where does that come from? It comes from centuries of racialized hierarchies in which one group assumes what is in another’s mind. It’s like moving backwards up a messed-up decision tree.

And first-generation immigrants learn the myth of meritocracy the hard way: If I just do my best, then that shields me from being harmed. I wonder about this idea of “just working hard” and “sheer talent alone,” and a pure system. But there’s no pure space without politics. We are all embedded in social reality and history. So when we claim an objective purity, purity for what, and to what end?

KR: It makes me think about a lot of stuff going on in the science fiction and speculative fiction communities. Recently, the prominent award-winning books have been suddenly from women of color writing science fiction. The backlash to those awardees is saying, “Everything is just political now. All the science fiction is all about politics.”

NK: There were the protests around the Hugo and Nebula award nominees.

KR:As if it weren't political, as if you were just writing about the future, and that had nothing at all to do with how the world that you were coming from functioned, or how what you wanted to live in the future wouldn’t relate to politics. That's the most stark, funny example of this purity to me lately.

TC:Also some of the responses are very emotional, and they usually come from people who feel like something is being taken away from them. They don't want to give up their positions of power and their representations as good or superior. It's fundamentally an emotional response, but then couched in rational language. It's like, let's just walk it through. Let's look at the numbers. The graduation rates. But people will find ways to justify their point, and they don’t always make sense. That wasn't really the point. The point was that they felt defensive and didn't want something taken away from them.

KR:Yeah. The friends who have come out strongly on this side have so much more to say to me, than I have to them. I remember after the Google Memo incident, I had older friends from college asking me, "So, what do you think about this?" I would say, well, it's stupid. Then they would just want to talk for 45 minutes about why they thought the Google employee was right, and about the memo and why it was important and why it was good. I had so much less to say, but they had been doing all this reading. Sometimes it felt like the reading and researching was primarily to not face their much more emotional, personal reaction. By reading and listening to podcasts and stuff, they would have an argument that they could present.

One of the more negative projects I planned, that I haven't done, was to take some of these emails that I was getting from friends and just make a bot to generate sentences to mimic them. They would all use the same language. It started to get to the point where if I just saw someone arguing about free speech, well, that plus certain other words, you just knew what someone would argue.

TC:I've actually been happy in some cases when people were not so sophisticated around the packaging of their ideas and straight up said what they were thinking. It gave me insight into what was really going through their minds before they may have found better language. I've talked to people, like Asian male engineers, for instance, who say, this is all we have, this is the only thing we're good at – why take that away from us? I'm like, oh. Our society is really deeply problematic. [laughs]

NK:And that is the precarity of a system that wants us to fight over little parcels of land. I think of the protest against tent cities in California, the growing conservatism of immigrants, and the violence engendered by the model minority myth.

What changes have you seen since 2013, when you started to gather data on women engineer hires in Silicon Valley and place them online?

TC: I think there's been some shifts in the conversation to be less about women and slightly more intersectional, which is positive. It’s less about let's get some data, map out the problem, and more, now we have data, what do we do to fix the problem? There have been some exploratory attempts at solutions, most of which have not been very successful, but you have to start somewhere. We've found some programs that work to mitigate bias. Other programs require a lot of effort. You see a bit of gains from them, but they can't be widely scaled; we haven't found very many successful scalable solutions.

So for example, some companies are doing apprenticeship programs, which are much more intensive on mentoring and onboarding people. It is great to be able to provide those on-ramps for people who aren't coming from the same, traditional feeder backgrounds. But it doesn't work to do that for most of your new employees. You don't have enough bandwidth, practically speaking, to continuing building the business and also onboard new people.

So, there has been some slow progress. One big change is that diversity is now a trendy PR thing for a lot of companies and firms. That can potentially be more damaging, because there are a lot of people who are raising this flag of diversity and inclusion and really aren't doing anything. They are actually counterproductive to the movement. This talking too much – without actually achieving – is also inciting some backlash, like some of the men who think it's all “gone too far.”

I think progress is going to be uneven. We'll make some forward strides, and then some will try to pull back. On the whole, at least the party line is that diversity is important. If that's what people are saying, eventually we'll start pulling in that direction, even if not everyone feels it yet. I think it's better that people say diversity is important than they say it's not important, even if they're not quite yet there with their actions.

NK:The alt- right challenge a shallow form of what identity politics really is, a neoliberal conception of diversity, a flatly marketed idea used as protection by many companies. Ignore our drones; look at our staff. Diversity is not just one different person in a room; it's also diversity of thought, engaging in other’s difference.

TC:What that's demonstrating right now though is, that that same group of people co-opting a lot of this language, even “diversity of thought,” they will also say, well, you're also saying you want biases, but not our biases. I think it falls into the paradox of intolerance. I forget the exact wording. Something like, “we cannot be tolerant of intolerance.”

KR:That's good. I'm going to write that down.

NK:So you create different paths of access, like creating an onboarding process when the resources aren't there. Kate, you put up simple, beautiful, and accessible tutorials for coding. You tell people that coding is difficult, acknowledge what that they might be afraid to ask in a classroom. Early programmers championed being an autodidact. When you didn't have access to a great education, you could teach yourself, tinkering in your room.

KR:That idea of the genius tinkering in his room – that is what the programming community is still attached to. It is the ideal. I got into a good Twitter with some statistician lady who was tweeting a seventh grader's homework assignment. It was a puzzle, about laying out five coins, more than a math problem. I said, oh, here is why I didn't get into advanced math. Then I never got to take calculus. I studied journalism, and then only later did I find myself programming.

When I tell people that learning to code is hard – my idea is that code is not just for people who have math brains, who are able to see the five coins and make a leap of intuition about how they should be arranged. For most of programming there are still certain areas that are highly mathematical, and machine learning is one of them. But most of programming is about being careful and thoughtful, and actually working well with people. Most time gets lost when someone's not paying attention to what someone else thought was happening.

I'm excited for when programming splits into something that's more like the work of biologists and doctors, rather than just being one field. Working at it and just being good at your job are really different from being the math genius sitting in a room who can suddenly make Google.

TC: That there are alternate ways to think of systems and alternate communities. The more diverse perspectives you have, you have more different ideas of what tech can do.

KR:Right. There's alternate ways to judge value in work too. Programming can be something that you can do, if you work hard and gets good grades. This tends to be what a lot more women are doing these days. They are going into higher education. This is better than romanticizing a 16-year-old math genius. The field then opens it up for a lot of people who didn't think that they could do that kind of work.

NK:Which kind of futures do you envision? Are there small moments from the last year or recently even that have made you feel that things are improving?

KR:When things start to go wrong, like with Facebook, we are blaming tech culture and the technology itself. As tech moves into every domain, we'll be able to start looking at the people in power who are making decisions, and how those are having effect on people. This is not a state of affairs specific to tech, even if the decisions are being filtered down through to technology. We will see the effects of their values on things.

“Values” is the kind of word that I use most now. I'm not just looking at a tech company, because that doesn't really describe anything anymore; I'm trying to find out what's shaping the way that they're making. We’ll become more and more able to separate out values, the human role in the making of the tools.

NK:So technical brilliance or ideological purity: these are not enough. You need moral intelligence, you need emotional intelligence.

TC:Yes. I think in the last year or two, we've seen a lot of wake up calls around technology, when it's not designed or implemented well, and those are bad things that have happened to cause us to wake up. I do like that people are starting to have these conversations. There's this one ex-Googler who's written really well how chemists and physicists began to see how their work could be weaponized, made into chemical weapons or nuclear bombs. They had to grapple with ethics. Those practitioners and researchers started thinking about not just what is possible, but whether it should be possible.

Software and tech so far has not really had that same kind of ethical thinking embedded within it. That will become more of a trend in the future. Hopefully more quickly rather than less. On the diversity front, more people are brainstorming and experimenting and committing effort towards increasing inclusion. We still have a long way to go, but there's some positive change.

Claire L. Evans and Tracy Chou:

Claire L. Evans and Tracy Chou:

The first sketches of what would become the Collectable.art app

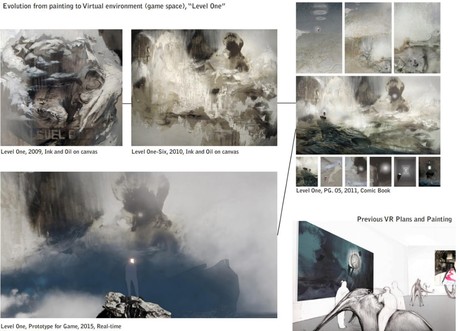

The first sketches of what would become the Collectable.art app The representation of the app’s interface in Xcode

The representation of the app’s interface in Xcode

.png)

_big.jpg)

_large.jpg)