This article accompanies the inclusion of Paper Rad’s Paperrad.org (2001-2008) in the online exhibition Net Art Anthology. Image: Ben Jones covered in zines, courtesy of Jacob Ciocci.

Lauren Studebaker: When Paper Rad came together you were in Boston, working on a project called Paper Radio. How did Paper Rad emerge from your other DIY projects, or the DIY scene that you were working in at the time?

Ben Jones: Paper Rad came from the community centered around a publication called Paper Radio. This was definitely before the word “zine” became a Portlandia sketch. Paper Radio was a project that came from being in art school and looking up to people like Raymond Pettibon, but also coming from what was then the Massachusetts underground punk rock and hardcore scene.

Jacob Ciocci: Jessica went to Wellesley College, in Boston. And I was at Oberlin College. We had heard about the Boston and Providence noise and comics scene.

Jessica Ciocci: Jacob and I were looking at zines a lot at that time, like homemade comics, and that was really inspiring to us. Jacob had always been more into comics than I was, but I would send him stuff from Boston that people had made that I would find since I was living in that area–looking for whatever was like a dollar or like clearly homemade and weird. There was a group of people at Mass Art, which is one of the art schools in Boston.

Jacob: After Oberlin, I moved in with Jessica, and we immediately tried to become friends with people that were already really active in that scene. It was then we met Joe Grillo, who was in Paper Rad at the beginning.

Through Joe we met Christopher Forgues, who works under the name CF. Christopher and Ben [Jones] had been doing a project in Boston called Paper Radio, which was a zine project. Free zines, usually probably stolen Xeroxes.

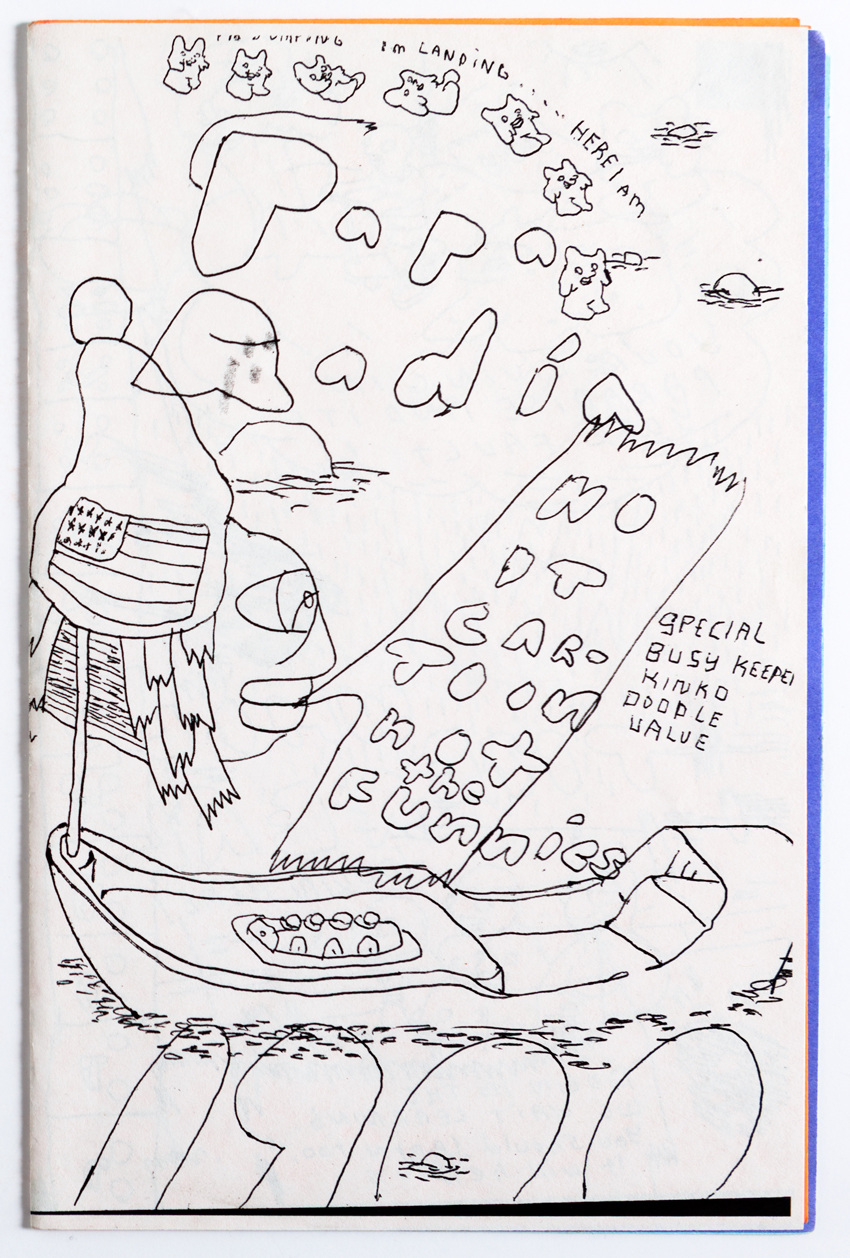

![]()

Paper Radio #7, 1999.

The zines that they were making already were really forward-thinking, in my opinion. They weren't typical diary-based zines about feelings, or vegan politics. They were really messy, they looked kind of just closer to avant garde collage, or literally some pages just looked like trash. I mean, they still kind of had a comic bend, but they were more experimental than your typical comics or zines.

Jessica: Ben was also making videos at the time and we were like, “Oh, my God. We have to see his videos. That's amazing.”

I think both of us were really into that multimedia possibility. Jacob had studied computer stuff college, and Ben was also working at some sort of computer job at the time. The internet was just, kind of, this goofy realm at the time, and we were like, “Well, oh, my God. We have to make a website and put this stuff online.” Because, you know, a lot of the other kids were doing something more handmade, not so technological.

Jacob and I saw Ben’s animations at some point, and we're big fans.

Jacob: We started hanging out with Joe and Christopher and Ben. And we started collaborating immediately, one of those types of friendships where it was work friendship. It wasn't just, let's hang out and drink beer. It was always, let's draw, or let's make a zine. A lot of that is Ben, too. Ben is very ambitious, and pretty much all of his friendships revolved around art projects.

Jessica: I didn't know anything about Flash, but eventually learned how to use it rudimentarily. We started making video mixtapes. The first Paper Rad video mix we made was in Boston and that was very homemade style, but it included animation and edited on a VCR VHS tape, like found video and weird home recordings.

Jacob: Everybody was in bands, too, but bands meant anything. Jessica and I had this band called Pracky Pranky, which was basically just us doing prank phone calls, and recording them. I think we performed one time. A band was a really loose term at the time.

Ben: In weird way, back then, a music show was, I think, as much about the visual nature of it, the flier, the experience, the whole experiential performative nature of it.

Jacob: There was this sort of lo-fi, 8-bit movement happening––what Cory Arcangel, Paul Davis, and 8-Bit Construction Set on Beige Records were doing–– and I think we were all really interested in what they were doing. Ben had already made a website for his own stuff. I forget what the URL was, but even that already had some things that would become known on Paper Rad, like using table art, which is basically HTML tables to make shapes or images out of just sort of blocky rectangles.

I was super into lo-fi web design, or what Cory [Arcangel] was calling “Dirtstyle.” Jessica also was into that. She took an HTML class like me in college, and the pages that we made were intentionally shitty looking. You know? They were meant to look like the vernacular web that we were excited about, not the sort of high-end design web, which is what artists were supposed to be doing at the time. Artists were supposed to be making these websites that looked really fancy, or, in some ways, showed expertise, or showed how you were separate or different from GeoCities.

I think, end of 2000, beginning of 2001, is when we started actually publishing the website. Ben had already been making his own Flash animations. There was already a lot of energy and steam underneath Paper Rad coming from Ben and other collaborators in Boston.

Jessica and I, we’re brother and sister. So, there was this kind of family dynamic that I think combined with Ben really created this sort of sense of an internal logic for all of the work, which was an informal, sort of outsider art family that had grown up on computers and cartoons, and were making all these things for each other, rather than for the rest of the world.

When the website was published, it felt like, oh, we're looking at this bizarre little community of people that have been kind of percolating and influencing each other.

Andrew Warren, who I mentioned earlier, was a collaborator on the website early on. And so was Joe Grillo, Laura Grant, and Billy Grant, who were also brother and sister. And they splintered off and formed Dearraindrop.

Ben: There was like 15 people that we knew. And I think all those people were like, “Oh fuck. This is genius. Can you show me how to do this?” Then I think that probably blew up in a way that I’ve never been a part of something that blew up so fast through the internet and through amazing places like Eyebeam or Rhizome or Oberlin and curators and New Museum and Lauren Cornell. I think Jacob and Jessica came from totally different, but a similar product of, at least DIY computing and certainly film making, in the sense of popular culture and media and music.

Lauren: A lot of the content produced by Paper Rad seems like a celebration of a youth culture––I would go as far as saying it’s a very specific young, positive psychedelic sort of tween culture from the 80s and 90s. What were the main influences visually, sonically? Where there other kind of collectives that were kind of inspiring your work?

Jessica: Maybe what was different for us was including more weird pop culture or the found stuff. And having a reaction to stuff that seemed, sort of culturally not cool. At the time, there was more of a leftover hipster thing from the late '90s, which was not embracing of cute stuff or '80s aesthetics.The bright colors were really gross to people, I think.

Jacob: In terms of influences, a huge one would have been Fort Thunder, which was a DIY space and collective from Providence. An online influence was JODI. I think all three of us had seen JODI in college. jodi.org was the site that seemed to be the most exciting to us because it had the same kind of confusion that we tried to embrace.

It wasn't, oh, this is an art project. It was, what the fuck is this? Is this a mistake? Is this broken? It existed outside of the sort of rigid context of art school, or the definition of art. And we weren't trying to do that, we didn't sit around and have conversations saying we want to try and do that, but that's what we naturally gravitated towards, that kind of space outside of art, but that was still was clearly artistic, or creative.

That idea of being outside of art was the other big influence. Jessica was really into finding and archiving little notes or pieces, ephemera from kids, or tweens, or teens. Anything that she could find that was handwriting, she was obsessed with, because handwriting sort of has this quality of revealing somebody's personality. It is creative. Handwriting is creative. But it's not high art, and so it's outside of that idea of fine art, even though it is art.

Jessica was making these zines that were filled with a combination of found handwriting, and her own. And you hit on it when you said tween culture. She was doing this handwriting that was based off of the handwriting she had when she was, whatever, nine, or ten, I don't know what age. But it was totally this stylized way of writing that, in zines and online, was really confusing to figure out if it was found, or if it was something that she did. It also made the website maybe feel like it was made by a 10-year old. A genius 10-year old. I remember thinking at the time that kid’s art was the last undiscovered genre of “outsider art.”

That was one of the most brilliant and fun things about our site, or Paper Rad period, was this confusion over what we made versus what we found. And in particular that it was about people that were outsiders, or we were trying to tap into this kind of more wild of version of creativity that exists outside of art school, exists outside of this idea of fine art, that can exist at a punk show, or but even more so exists just in people's lives.

Lauren: That to me seems very disparate from the existing Boston hardcore scene at the time.

Ben: Let's just even reduce it to color. Paper Radio was like brown and punk rock colors. Like rusty orange. And I think the first time I saw Jacob and Jessica, they were dressed in neon.

What Jacob and Jessica were doing, I think is, I don't think it was a reaction. Honestly, I think they were truly just tapping into who they were. You could say that we were reverting to literally how we dressed as children, but in a weird way. I think, seeing how things like Odd Future and Tyler, The Creator can completely change the visual language by the way they dress and the colors they embrace. It didn’t and doesn't seem contrived to me.

Growing up, part of my identity was rooted in neon colors and BMX, and even I consider video games and RGB. It's like, all these bright saturated colors. And I think if anything, when Jacob and Jessica came into this space, I realized all this punk rock bullshit was this artifice that I was co-opting to fit in based on an older generation’s expression, but it was kind of bullshit for me. So I saw it and I was like, “Oh fuck. This is real. I can speak to this.” But, I'm also not a dummy. I was like, “This is totally different and this will certainly …” and probably this is what prompted us to do a name change to Paper Rad, because it was something totally needed and different and would be disruptive.

Lauren: I think you can say also, let me know if you disagree, but looking at the work, there's definitely kind of this ethos of a new age positivity. Why? Was this an embrace or a criticism of this style?

Jacob:It was both. And also it was that me and Jessica's parents, kind of had a new age moment. Ben's mom, especially, had one. I think hers was a little more long-lasting than our parents'. But, I think in interviews in the past, I've said the three of us grew up in new age households, kind of surrounded by crystals, and these magazines that would be selling new age merchandise.

The magazine, for example, is a great sort of distillation of the approach we took to it, which was, on the one hand, the stuff is super fascinating and fun, but on the other hand, it's clearly consumerism. Cartoons and comics are consumerism. So, we embraced all of it with a sense of positivity, but I think we also knew that it was trash. I think part of why named our first major release DVD, Trash Talking.

Related to that was this idea of just being non-judgmental about the pros and cons of everything, but that includes spirituality in particular, and new age spirituality, and this sort of post-hippie embrace of Eastern gurus in the United States, and all of the merchandising that came out of that.

In addition, the positivity was a reaction against what was happening in the underground in the 90s. Indie rock, emo, these things were dark, and so serious. I remember being really inspired by Andrew W.K., who, when I first heard his music, and saw this persona that he'd created, I wished that I had come up with that idea. He sort of did a pop-metal positivity, and I think what I was trying to do was more of a young, new age boy who's into fantasy art positivity, like, you can use this crystal necklace as a way out of sadness or suffering.

And the peace symbols, yin yang symbols, all this stuff was sort of, on the one hand, really important magical messages, and on the other hand this kind of shit that you find at dollar stores and stuff that's, like, at beach ... We would go down to Myrtle Beach, I can tell you more about that later, but there was this store at Myrtle Beach called The Gay Dolphin, which was just basically a three-story, massive gift shop in Myrtle Beach. And it had so many dolphins, and so many peace symbols, and yin yang symbols, and it was an oasis, a utopia, and a nightmare at the same time. You know?

Jessica Ciocci: We're all from a generation of where our parents were hippies, so we were exposed to the new age, like the potentials of all of it. In the late '60s-early '70s, there was all this potential of peace and art being revolutionary. I don't know. I guess in the '70s, people were kind of disillusioned, and in the '80s, everyone forgot about it. I don't know what happened.

It just became like a materialistic realm, and maybe that's part of why we were drawn to the shallowness of some of that imagery, but we were also trying to reinvigorate some of it––put some heart back into some of the cheesy ideas of the new age or the hippy movement. Some of that is just genuinely appealing aesthetically, or also weirdly contrasting, like you were saying, to the more serious, or hardcore intellectual scene in Boston.

Lauren: Paper rad emerged during the “dark ages” of the social web––that period after the dot-com crash and before Web 2.0 platforms like Youtube and Facebook were founded in 2005–2006. How do you think the work reflects era of the internet? Do you think this web landscape influenced the work?

Ben: A way to investigate this is through personal computing. And I know it’s crazy, but until Apple and Atari came on the scene, people weren’t allowed to touch computers. So that generation that said, “No. Computers is this DIY thing that everyone should have in their house,” is a huge influential thing. And I think that’s what my dad was a part of and that was kind of what we were doing, not in a way to be disruptive or revolutionary, but we were the, not culmination, but we realized, with these computers, we can start to make our versions of television shows, the internet is just a point of distribution, like a zine.

You look at an invention like the steadicam or a handheld camera. And you see how different filmmakers use that. And you get things like Easy Rider which changes everything. Or you get Stanley Kubrick using his steadicam in The Shining. And that just reinvents how we experience film.

To us, I think we were just really good at using the tool of computer programming. And even at that time, HTML and registering a URL, those were pretty rare. So we had that skill set, where we could make websites. Which, now, we take for granted, but back then, that in itself was amazing. We could get, Jacob and I could just get any job we wanted, because we could lie and say we could build websites. So we used that, again to tap into this authentic expression, like any artist does, of exploring their childhood and their hopes and dreams and influences.

So I think what was more interesting about pre-YouTube, post dot com crash, was that we were using the tool, not to examine the tool itself. We were just using the tool to really world build, as much as filmmakers with a steadicam.

Jessica: I remember MySpace coming along and then being, like, “Oh, okay. What are we going to do now? We can't have a Paper Rad MySpace.” but I thought it was kind of cool because I could just have like a personal music account and still connect with other people, so it was kind of part of Paper Rad. Yeah, it definitely felt weird.

YouTube, when that came out, I remember being like, “Oh, this is going to change everything.” Just like free, really easy to find, weird videos, like now you don't have to go look for VHS tapes on the street, or in thrift stores. It sort of made us feel like it made some of the stuff we did easier or, like, unappreciated. I don't know how to put it. I think Jacob, kind of adapted to that well by using YouTube stuff early on in his videos that were still Paper Rad.

Jacob: Once YouTube happened, Paper Rad started to mean something really different. Because a lot of the DVDs, and the VHS tapes, and the video that we made, was based off of sort obscure found footage from children's entertainment, or bizarre tapes that you would find at a thrift store. And we would contextualize our own animations within that.

And then, once YouTube happened, it became really easy for everybody to watch those sort of weird things. So, what we were doing pre-YouTube was distributing as well as packaging our own work within these DVD or VHS compilations that we would make. And that was because it didn't exist online at all. And we didn't even publish those DVDs, or VHS tapes online, because there was no streaming. There wasn't really the infrastructure for it.

I think our site seemed like a beacon for weird or strange graphics and animation. It was also pre-Tumblr, so this idea of collecting or archiving bizarre images from the past, from particularly the 80s and early 90s, was not something that a lot of other people were doing online. I'm sure there were nerdy sites for people collecting comics, or comic books advertisements, or weird images. But they didn't have the sort of confusing interface that we had. Our interface was intentionally really hard to navigate, as well as, I guess… the easiest way to put it is just that it was confusing, or junky.

The stuff that we were finding, scanning, and uploading was all within that maze-like context, rather than an easily organized archive. There’s this whole generation of art students that were in art school in the early 2000s, that always come up to me and tell me that they would look at Paper Rad every day. And I think it's because there were very few other people that were delivering this style of content which is now all over social media.

But we were one of the few people to do it for a browser, at the time. Other “net-art” sites had this kind of serious air to them, and I think Paper Rad was basically just a mysterious sort of, “fuck you” to all of that. This was also pre-Adult Swim, but if you were into skater stuff, or punk stuff, or psychedelic art and also happened to like computers…. and I think a lot of kids that were into drugs–you would probably look at Paper Rad late at night.

Lauren: Despite the DIY energy of Paper Rad, you’ve most definitely become a part of the contemporary art canon––the first time I came in contact with your work, or even Cory Arcangel’s work for that matter, was seeing Super Mario Movie in an intro to media arts class in college. You all also had group and solo exhibitions at New York galleries like Foxy Production at the time. As a DIY collective focusing on “low-brow”content, how did things change when you started to be accepted, or brought into the contemporary art world?

Jacob: Well, the main thing I want to say is that the scene was so strong, the community was so strong at the time, that we were really buffered from taking the art world too seriously. Which actually had its benefits and its curses. But what I mean by that is that, we took it with a grain of salt. So when we would do a show, it would be kind of, like, okay, here's this weird thing I'm going to do, it's important, but it's not as important as my friends, and the community that we had in Providence, or Pittsburgh, or Western Mass or Baltimore.

So, it allowed us to kind of just do what we were already doing and not really worry about making money. But there was a downside to that. We didn't realize in a way how, well, I'll just speak for myself, and say, I didn't realize how special it was that we were getting invited to do this stuff. And when I say special, of course, at the time I would have said, it's not that special, it's not as special as Fort Thunder, that's for sure.

And that's true. It's still not as special to me as Fort Thunder was. But there's something to be said for art history, and, in particular, this dialogue that's been going on for a hundred, two hundred years. There's a lot of gatekeepers; there's a lot of people that don't want to have weird stuff like this in that dialogue, and we did have that opportunity. I think when you're younger, you don't really think about the long-term as much, and so I was like, it doesn't matter. Art history doesn't matter. What matters is me and my friends.

And now, friends are moving on, everything's changing, and art history sort of matters again to me. Art, for the first time.

I think we didn't really change what we were doing that much. Ben kind of realized that we needed to, or that we should figure out some strategies for making things make more sense in the gallery. And we figured that out sometimes better than others. But it really was a weird sort of family getting plopped into a gallery, or an art space for two weeks, or a month, and having to figure out what we were going to do, and arguing about it, and then just making a mess, and hoping that it would sort itself out. That's how it felt.

And it usually worked pretty well, for the kids especially. The shows would be big hits for young kids, and not as big hits for collectors. Some of the things really worked well for collectors, I think. Or for the press. But other things were really, like, oh shit, this is a cool art show for young 20-year-olds. This is rare. This isn't something that usually gets to happen, that a kind of art that speaks to 20-year-olds is allowed to be at a museum, or at ... a big space. Deitch had been doing that for years but they had yet to figure out that computers were about to become a big part of what being cool and young was about .

In terms of that, the show we did with Cory Arcangel at Deitch was a big hit, because it was easy to digest. It was just one piece, the Mario movie. And it was able to kind of both work within the art world context, and our context. Cory's context as well. I was in grad school. I loved art, you know? Art history, even then. Paper Rad had already started, and I was like, uh, I'm going to go to grad school, and I moved to Pittsburgh.

So, I clearly already had staked my claim as, this is going to be my life, this whole idea of fine art, however flawed it is. By the time my show at Foxy happened, that was my thesis show from my grad program. It's so funny, because at the time I thought I'd figured it all out, how I was going to handle that context. And now I look back on that show and I just think how naïve I was, and how little I'd figured out.

I think Jessica's show at Foxy was actually the best of the three. Maybe because it was the last, but also because her work worked the best in that space at that time. It just seemed like the most mature, or whatever, of all three of the shows that we did. I think there's some really good pieces from the solo show that all three of Paper Rad did together. Our first Foxy show, there's this piece called the video comic which I think is really good. I think Ben probably came up with that idea, but we all three kind of made comics for video monitors, moving Flash comics, and all three of them are really good, I think. That piece, it needs to be shown again.

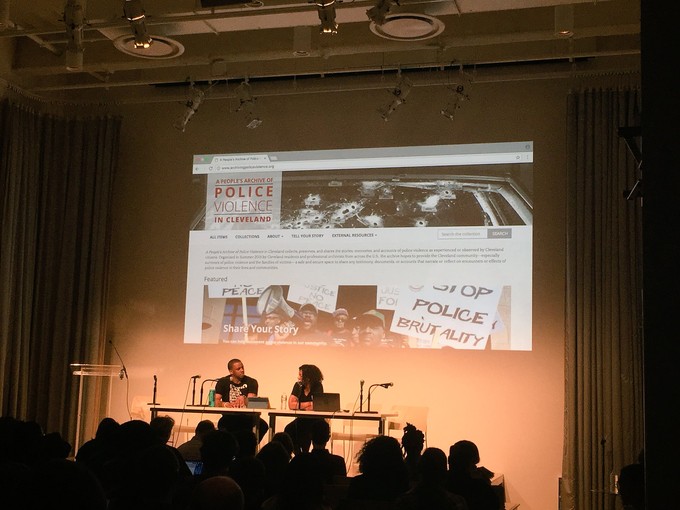

![]()

Paper Rad at Foxy Production, 2004.

There's really big hits that I think will resonate within art history, that have just been totally lost, because people are just like, oh yeah, Paper Rad, they were that youth art thing that faded away. But, I think, as a collective, we did a lot of things that will continue to resonate, and make sense within art history.

Jessica: It was all a wild experiment. I definitely felt like to get into the fine art world maybe wasn't necessarily ever a goal. I guess it did feel like a conflict in a way, or like having your feet in two different worlds. Something like that. I think it did––I'm not going to lie––definitely produce a lot of inner conflict or turmoil and a weird questioning of what are we doing?

But, it was fun. I was really happy to do those shows, like the solo show at Foxy [Production]. Maybe that's something I find particularly unique was that we were doing gallery shows and stepping into that world a little bit, but also still, to warehouse spaces and playing some weird show and handing out $5.00 merchandise.

I never really wanted to be exclusively involved in galleries. I think a lot of it evolved from connections with friends, but now that I think of it, it's probably very specifically from Jacob knowing Cory from college. I know that Cory organized some show at Foxy Production when they were still in Brooklyn and we were invited to be a part of that. That's how it came to be. Around the same time, Foxy asked us to do a show as Paper Rad. It was then like, “well, how do we market this?” Since we were a collective, it's difficult. People didn’t want to buy something like that. It's too confusing.

They suggested doing solo shows, trying to have each of us have a show to see if it could be sellable that way. I mean, I sold a few things. I actually think my show did better than Jacob or Ben's. That's a little point of pride for me, I guess.

Ben: So, the fact that we were incorporated into the art world in any given way, that was on the art world's terms. I think they very quickly saw that we didn't really serve them––look, it could have gone either way. No, I don't think it could have gone either way. I think I was never interested in hacking that system. And the fact that we were both in the same gallery in 2000 whatever, was kind of the genius of that gallery owner and less about our response to the art world or the art world itself.

Lauren: Was archiving a concern while Paper Rad was going on?

Jacob: No!

Lauren: Do you think a lot of things were lost?

Jacob: Fuck yeah! It's tragic. A lot of it is digital; a lot of incredible files are sitting on computers that have been thrown away, or decayed. I think the zines have been documented okay. There's a lot of actual painting and drawing that's been lost.

It's like an old relationship. Do you really want to go through all of your old love letters, and scan them, and organize them, after you've been heartbroken over that relationship? You don't, you know?

People ask, “Why didn't these artists archive their stuff better?” It's because it’s painful. And that's even true if you're just an individual artist, because there are all of these projects that are unfinished, or half-documented; they have an emotional weight to them that is hard to face.

Lauren: Do you see remnants from your time in Paper Rad enter into the work you’re making now?

Jacob: Totally, yeah. I went to grad school, but my real grad program was Paper Rad. I feel like it was a school that I went to and I learned all of these techniques and methods through Ben and Jessica that I now use every day when I make art. They're kind of like my teachers. Ben and Jessica were my main two professors, and then Joe Grillo was a professor, and then people at Fort Thunder, and Cory, and David Wightman, others were professors, too.

This whole idea of that family, that community, I sadly don't really feel any of that anymore, but I'm still using all of that methodology within what I do now. It almost seems like this post-apocalyptic landscape. So, if that was a more utopian era, this is a dystopian era, but I'm still doing that same practice, in a weird way.

I think the thing that carries over the most, the reason I'm still doing that, is because with Paper Rad, and Fort Thunder, and other things of around that time, there was just this ethos of, you can't rely on anyone to do anything for you, and you have to make it happen all by yourself, no matter what. And that still feels true to me. I love deadlines, external deadlines really help me a lot. But, at the end of the day, I have to want to do things because I want to do them for myself, rather than as a product for someone else, or something.

The art world is so ephemeral, and it can come and go with its amount of support for you, or its amount of care for what you do. And that's true for the commercial world, too. The only thing that you can really count on is yourself, and your own productivity.

And so, Jessica's doing that. She's totally independent. I think that sense of, you make art because that's what you do, regardless of who's looking at it, who's watching it, is key. And it also relates to what we're inspired by, like I was saying, outsider artists, or people that are totally creative outside of the regime of art. That's what they do. They're just making things because they have to.

Ben:. Great art in the Hollywood sphere and in the art world, is just work that’s really true to itself. Even if you're Jerry Seinfeld or Garry Shandling, you just need to tell your story. What happened to you today, how did that make you feel? So in that sense you need to go back to your parents and your experience and your own voice and who you are, to that point. That was a large part of Paper Rad, who we were and why it was that optimism and that non-cynical approach to the content and the color.

And I don't think I'm trying to leverage those superficial qualities in Hollywood, but I think I am trying to tap into characters and stories that are true to myself and that do reflect that tone.

Jessica: I think like the energy is continuing in the stuff I make now and of course, that is very DIY because I'm not in the art world where I have resources necessarily at the moment. I don't have a studio with assistants. What I'm doing now is very DIY. It’s just on my own, you know? The other aspects of Paper Rad are very important to me too, like homemade art, and making within whatever means you have.

There's something about that I believe in. The things that I'm inspired by, outside of my work and in the world share that. Like going to see new weird bands in the noise scene, or experimental music. That's still going on, and that's probably where I find the more collective aspect of whatever was inspiring Paper Rad in the beginning. So it's still there. It's maybe not as formalized or official.

Maybe that's why Paper Rad was such a strange thing. It was like, “Hey, here are all these things that are, kind of, in the air, but we're going to call it an organization, or a group, and present it to you in a funny way. Sort of, like, a colorful, goofy, loud, and (hopefully) fun way.”

Image Credit: Caroline Sinders. To watch the full video of this conversation,

Image Credit: Caroline Sinders. To watch the full video of this conversation,  Patty Chang, Shangri-La, 2005, 40 minutes , single channel video installation.

Patty Chang, Shangri-La, 2005, 40 minutes , single channel video installation.

.jpg)