This is the first post in a series on the queer history of computing, as traced through the lives of five foundational figures. It is both an attempt to make visible those parts of a history that are often neglected, erased, or forgotten, and an effort to question the assumption that the technical and the sexual are so easily divided.

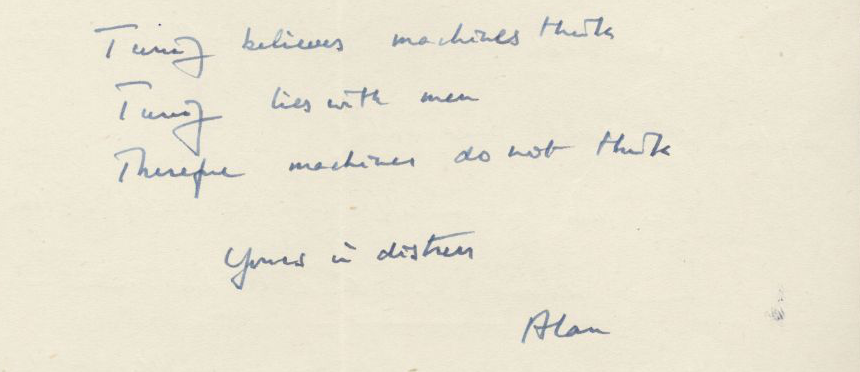

Alan Turing, Letter to Dr. N. A. Routledge, AMT/D/14A Turing Archive

There are many ways of telling the history of universal computation, and many origins of the technologies we now consider computational machines. A longer history might begin with Gottfried Leibnitz and Isaac Newton's simultaneous development of modern calculus and the dream of a universal artificial mathematical language. Alternately, we might look to the history of calculating machines, beginning with Charles Babbage's Difference Engine or Herman Hollerith's Electric Sorting and Tabulating Machine.

Most every history would certainly include the contributions of Alan Turing, an English mathematician who is considered by many to be the father of computer science. In his relatively short career Turing formalized such concepts as "algorithm" and "computation," he helped crack the Nazi Enigma Machine during the Second World War, was a pioneer in the field of artificial intelligence, and developed early research on such concepts as neural nets, morphogenesis, and mathematical biology. Turing was also an openly gay man who, in January of 1952 was convicted of Gross Indecency by the British government under the 1885 Labouchere Amendment, made to undergo chemical castration, and ultimately committed suicide in June of 1954.[i] The subject of numerous books, films, and works of art, Turing is perhaps the most widely recognized computer scientist in the field's short history. He is also the most recognizable queer figure in this history. As such, it is necessary to begin with Turing, not simply for the visibility of his difference, but for the fundamental role he played in defining the limits of computation, and the possibility to look beyond those limits in identifying a queer history of computing.

Homosexuality was by no means unheard of in England at the start of the 20th century, and by some accounts it seems to have been common practice among many college-aged students in elite universities such as Cambridge, which did not admit women until 1948.[ii] Still, homosexual activity had been explicitly illegal since the end of the 19th century, when it was famously used in a pair of legal cases against Oscar Wilde beginning in 1885, leading to his imprisonment and eventual exile in 1897.[iii] Given this legal status, what is most striking about Turing is how open he was with his sexuality, which seems to have been common knowledge among friends and colleagues. As Elizabeth Wilson notes in Affect and Artificial Intelligence, Turing's relationship to his sexuality seems to be less one of repression and shame, and more a kind of naïve amusement. If this attitude was not shared by others at the time, it was at the very least tolerated among Turing's friends and associates.

Donald Michie, one of Turing's wartime colleagues at Bletchley Park,[iv] recalls that "Bletchley had some flamboyant homosexuals,"[v] and that, despite the assumption that homosexuality would be considered a national security risk due to blackmail and other threats, it does not seem to have impeded Turing's work for the government, at least not during the war. For many in those days, homosexuality was an open secret, if it was kept secret at all.”[vi] But while Turing's sexuality is not in dispute, the effect it may have had on his life and work is much more speculative.

Alan Turing and Christopher Morcom, 1928

Turing's earliest and strongest romantic interest was with a young man he met at school named Christopher Morcom.[vii] Morcom, like Turing, was an aspiring scientist and mathematician, and Turing viewed him as both a peer and an inspiration, and as someone with whom he might share a budding enthusiasm for the technical world. While any romantic feelings Turing may have felt appear to have been unrequited, the two developed a powerful friendship. On February 7, 1930, two years after meeting Turing at University, Morcom fell ill with bovine tuberculosis, and passed away six days later on Feb 13. On the night of February 7, Turing recalls having a premonition of Morcom's death, at the very instant that he was taken ill and felt that this was something beyond what science could explain.[viii]

The death of Morcom would have a profound effect on Turing, particularly in shaping his views on religion, mortality, and the materiality of the soul. Turing had been a harsh critic of determinism, and with the death of Morcom he hoped to find a way to account for concepts such as free will and the spirit in a grounded, material way. It is this philosophical disjuncture that would lead Turing to theorize the limits of procedural knowledge, a concept that is central to his definition of computation in On Computable Numbers. To suggest that it was his unrequited love for a young man that inspired Turing to engage the questions that would establish a definition of computation would be facile, but to ignore the significance of these details parses what is technologically significant in such a way so as to exclude the personal, the emotional, and the sexual.

Surprisingly, there are few serious treatments of Turing as a queer figure,[ix] perhaps due to the difficulty in applying anachronistic language to historical figures such as Turing, or because in many ways Turing's work does not immediately lend itself to a radical queering. While we might argue that computers have come to play an important role in the formation, organization, and articulation of modern queer identity, this may have less to do with some aspect of computation that is inherently queer, and more to do with the broad indifference of these technologies toward such distinctions and the ease with which they facilitate contact and produce community.

Still, it is significant that one of the foundational figures in the modern history of computing was an openly gay man. We know more about the details of Turing's private life than any other figure in this history, due no doubt to his exceptional significance as both a scientist and a homosexual, categories that we cannot easily separate.

Turing's biography is no doubt familiar to many, particularly in the year following innumerable events celebrating the centenary of his birth, and a very public campaign for a posthumous apology for Turing's treatment by the British government following his arrest. Perhaps less familiar, though, is the genealogy of influence that radiates out from Turing, and which includes several foundational figures in the history of computing, all of whom were queer men.[x] These men were friends and acquaintances, mentors and colleagues, each driven by a passion for mathematics and the emerging field of computer science. As I will show, it is unclear what knowledge, if any, each had of the other's sexuality, or what effect such knowledge may have had on their relationships both professional and personal. Nonetheless, it is significant that such a connection exists, and in this connection lies the beginnings of a speculative history of queer computing, beginning at the very origins of computation itself.

Still, this connection is in part a fabrication, an attempt to make narrative that which largely escapes history. For most historians of technology, questions of sexuality are irrelevant to the technical achievements of an individual, and while queer historical work exists for significant literary and cultural figures, very little work has been done on queer figures in the history of technology. This may be due to the guarded lives these men led, and an almost total lack of personal biographical information available in existing historical accounts. Even the archives of these figures are in many cases lacking, as material relevant to the personal lives of these men is often excluded or withheld.

This division between the personal and technical is significant, and with few exceptions these men seem to have internalized this distinction, living lives that moved between worlds both public and private. These men lived in times radically different than our own, times in which the contexts and dispositions surrounding homosexuality were undergoing dramatic transformation. Just as computers evolve over the course of the twentieth century from simple tabulating machines to complex, interactive, expressive systems, homosexuality is also transformed and recoded, burdened with visibility and identity.

What then is the significance of the sexuality of these men? Why should we insist that they be remembered not only for their technical achievements, but as part of a broader queer genealogy? In part we may hope that, by incorporating them into the history of queer struggles for recognition and visibility, we recuperate and validate a part of their lives that was deliberately hidden. As historian Heather Love suggests, "by including queer figures from the past in a positive genealogy of gay identity, we make good on their suffering, transforming their shame into pride after the fact."[xi] Yet in doing so, Love argues, we erase the negative dimension that profoundly affects queer historical subjects. Theirs is not necessarily a history of pride and redemption; often it is a history of shame and even death. Rather than ignore this contradiction, my hope is to foreground it. It is in the disjunction between the professional and personal lives of these men, in the apparent incompatibility of sexuality and computation that I hope to develop a queer capacity within the history of computing.

Over the coming weeks I will be constructing a queer history as told through the figures of five men, each of whom is connected by a thread that runs from the early philosophy of mathematics, through the foundation of the Gay Liberation Front, and to contemporary debates over the life and legacy of Alan Turing. However the goal of this project is not biographical; it is not my hope to simply identify existing queer figures in the history of computing as an inclusive gesture, as a way of queering history by simply demonstrating that, as in all parts of life, queer people were there. Instead I hope to suggest that queerness is itself inherent within computational logic, and that this queerness becomes visible when we investigate those cleavages that partition the lives of these men into distinct technical and sexual spheres of existence. Ultimately I hope to show that there exists a structuring logic to computational systems that, while nearly totalizing, does not account for all forms of knowledge, and which excludes certain acts, behaviors, and modes of being. By situating this work historically, we can address computation from those early moments of experimentation and emergence before the field crystallizes into a discipline and an ideology. In doing so we discover a kind of liminal technical space of something not yet actualized. Finally it is my hope that through this history we can disturb the archive and begin to draw new connections between the personal and the technical. While it may not be possible to argue that the queerness of these men and of this history is what shapes present day computing technology, in establishing an existing queer history of computing we might critique the tendency to rend the one from the other.

[i] This is not to suggest that Turing's conviction was directly responsible for his suicide. In fact it is not entirely clear that his death was a suicide at all. While the hormone treatments he was made to undergo may seem horrific, Turing seemed to take a lighthearted approach to his predicament. While his death by cyanide poisoning – presumably from an apple found on his bedside table – was ruled a suicide, his mother insisted it was a simple mishandling of laboratory chemicals.

[ii] The homosocial environment of British University life is documented in numerous fictional texts of the time, several of which were written by authors of the Bloomsbury group such as E. M. Forster and Lytton Strachey. Perhaps most notable among these is E. M. Forster's Maurice, a love story of two men written between 1912-13 but published posthumously in 1971. Other more contemporary examples include Julian Mitchell's play Another Country (1983), later adapted into a feature length film (1984).

[iii] Sex between men had been illegal in England since as early as the Buggery Act of 1533, but the Labouchere Amendment made all forms of homosexual contact between men a punishable offense.

[iv] Bletchley Park was the estate that housed the National Codes Centre during World War II, and was the site at which the British broke the Nazi Enigma Code with the help of Turing.

[v] He continues, "The most flamboyant case was Angus Wilson – he later became a very successful novelist – and he had a boyfriend called Beverly. Angus was about that high [indicating small] with flowing yellow hair (l remember it went white later) and Beverly (I forget his second name) was very 'weed-like': very tall. They could be seen shambling along the horizon, a daily sight, as they look their walk around lawns alter lunch." Quoted in: Lee, John A. N. and Golde Holtzman, "50 Years After Breaking the Codes: interviews with Two of the Bletchley Park Scientists" IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, Spring 1995, Vol. 17 No. 1, p. 38.

[vi] It seems important to note that, as with much of British society at the time, there is a very particular class dynamic at work here, in which the upper class is often given more leeway with the law and among their peers. Of course this kind of homosexual behavior was not particular to the upper classes, and in fact homosexuality often facilitated a form of cross-class sexual contact.

[vii] Hodges, Andrew. Alan Turing: The Enigma. London: Random House Publishing (1992) p. 35.

[viii] Hodges. Ibid. p. 45.

[ix] This is not to suggest that Turing's sexuality is not widely acknowledged and discussed. Andrew Hodges – Turing's biographer, archivist, and a renowned mathematician himself – deals with Turing's sexuality explicitly in his writing, going so far as to speculate on the ways in which it may have motivated his personal and professional life. Elizabeth Wilson also deals with Turing's queerness in Affect and Artificial Intelligence (2010), though it is through the lens of affect theory and in regards to Turing's contributions to the field of AI. Turing is dealt with most explicitly as a queer subject in Jeremy Douglass' Machine Writing and the Turing Test which explores the implications of the Turing test in terms of gender "passing."

[x] Many queer women also make up the history of computing, though they are not connected directly to Turing through this particular genealogy. Lynn Conway is one such figure, who was an early pioneer in the American computing industry, studying at MIT in the 1950s and working for IBM in the 1960s. She would go on to make fundamental contributions to the revolution in Very Large Scale Integration (VLSI) design in the 1980s, and in 1999 would become an activist for transgender rights and visibility.

[xi] Love, Heather. Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (2009) p. 32.

Dan

Dan Micaela

Micaela Matt

Matt