![]()

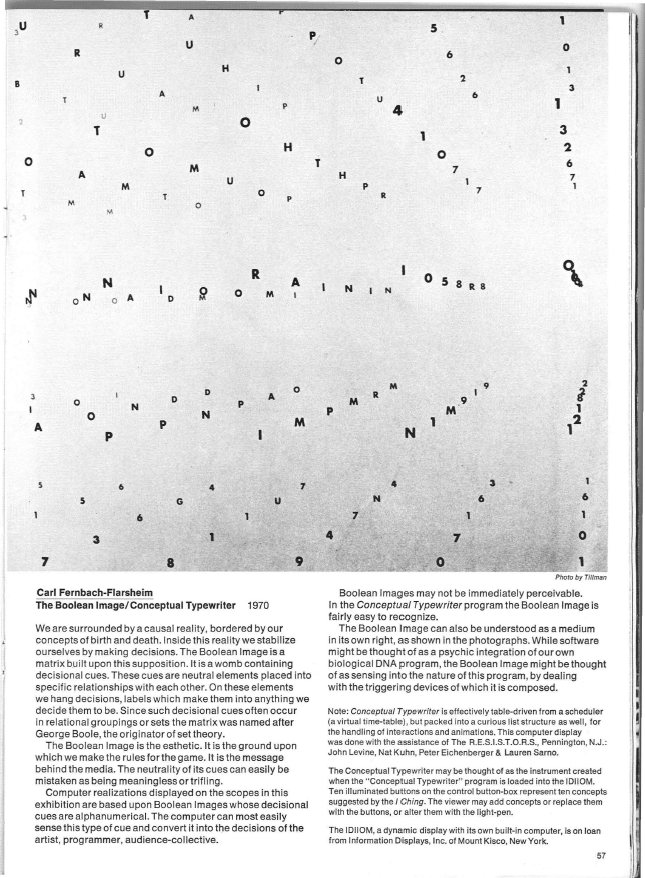

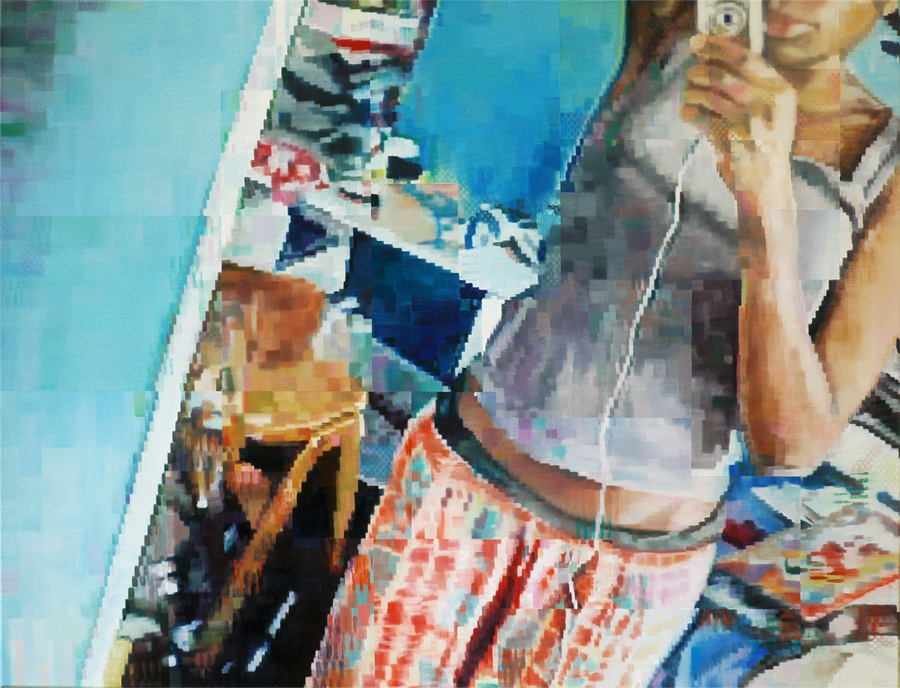

Still from Warm, Warm, Warm Spring Mouths 2013, HD video with 5.1 surround, 13'. Commissioned by Film and Video Umbrella and Jerwood Visual Arts.

Your video installation Us Dead Talk Love, currently on view at MoMA PS1, makes use of hi-def and surround-sound technologies. How do you approach these in your video installation process? How did you approach the installation specifically for Chisenhale?

It's predicated on immersion, I suppose. An attempt to address the body whole, rather than privilege sight, hearing. This might begin with a redressing of the balance between ocular and aural, and pan down to take in the whole wobbling form, up to some emotional affect – the surround sound penetrating, the visuals interrupting and shifting themselves between depths of field and vast cosmic spaces; infinitesimal motes of dust. These technologies are corporeal in their totalising address, which I see as dichotomous to the material reality of the technology – which seems to be dissipated or perhaps simply deferred to some desperate mine in some OTHER continent. The combined effect being one of possession – the work finding its home entirely within the body of the audience.

You've spoken of the tension between text or writing and filmic realization in your work before. How did this tension come into play during the production of your work in Us Dead Talk Love? Was it exacerbated or sublimated by your chosen technologies?

If I had to choose, I'd say sublimated – though I think that it's more straightforwardly performative. The one to and of the other. New media as a home for these things. Whether that's somewhat apologetic for the a failure of these things to stand alone is moot, I hope.

You've mentioned before your exposure to Hollis Frampton. What influence did Frampton have on your work? Certain sound editing in Death Mask 3 (2011) seems to me reminiscent of Frampton's experiments with vertical montage.

I came to Frampton – and much artist moving image – very late, in the primary form. It took a long time to retrace my influences: I'd basically 'read' work that was the direct but rather distant descendants of Frampton. Editing in particular, certainly – more specifically a certain structural troping. Frampton's harmonious approach to montage in relation to sound and its rhythms and discords and editing possibilities was something that had trickled down to me via other artists and possibly more popular formats who had priorly copied or expanded upon Frampton's thinking. And, I suppose, via Scratch Video and the technological possibility of new media.

Finally, I'm wondering if you can talk about the apparent concern in your work with cinema's increasing immateriality, which you've previously spoken of as the "hyper-materiality of the image itself" combined with an empty body.

I suppose what I mean by that is, in the absence of a body, a tangible medium or body, there is different kind of materiality described – one that is deferred to some other, subterranean situation – somewhere far away from the digital pinnacle. The appearance, at least, is of immateriality. That this lack of physical resolution, but rather a haunting of different physical situations, in the experience itself – in the experience of the video or the music, might engender a contrary accumulation or emphasis of matter in those other analogue agents involved in the encounter. This would include the body of the human watching or listening or experiencing or whatever – being addressed as gut as much as brain – and also the subject of the digital document. HD – at whatever current height it's reached (4K, 48fps?) – seems testament to this compensatory movement of material truth away from the body of the medium to… here, into the image. The surfaces depicted are vivid to the point of excess, to a point of imbalance, where subjects – subject matter – begins to die off, GETS BUMPED OFF – to be turned, in a blink, into dead matter – as a direct result, I think, of the weaponised heights of representative acuity. Like a knife with an atomically thin edge (obsidian), HD has the potential to murder its subject and present a great dermic husk of matter in its stead – all hair, skin, makeup, bruises – moving according to some occult, silicone anima. As youtube DAZ tutorials teach us, however, the actual weightlessness of these cadavers serves to describe their hollowness. Wireframe forms are skinned and rigged, but what about all that echoing space inside? To me, problems of ignorance in the face of these new modes, bodies, mortalities are very different to the ideological illusions conjured by analogue moving image – more difficult to expose, to undermine or ironise. I confess, I don't know much about an iPad, let alone how to make one – but it seems to know rather a lot about me, discerned, apparently, as I caress it. I'm thinking of Yul Brynner, a flask of acid flung in his face.

![]()

Still from Us Dead Talk Love 2012, Two-channel 4:3 in 16:9 HD video with 5.1 surround, 34'

Questionnaire:

Age: 30

Location: London

How long have you been working creatively with technology? How did you start?

The gap between fiddling with tech and 'working creatively' with it is perhaps a question of responsibility. As in, making sense of computer-oriented stuff as a legitimated, skilled thing – or perhaps as economically valid. Perhaps the gap between play and work is terrifically slim, requiring simply a maturation of perspective. Or perhaps it's the point at which medium specific reflexivity appears – when the previously transparent suddenly goes opaque, unwieldy. Not sure. I've certainly been writing, designing and drawing using software since my first Commodore. I know sincerely that I can't properly write longhand any more – not without great difficulty and a cramp within a couple of sentences. But I could till a few years ago. When I first got a laptop, perhaps. Maybe there was something about a laptop that finished the usurpation of analogous tools in terms of expediency and I started living properly through the computer. For everything, more or less. I made my first video from chunks of Tarzan movies and sample libraries of saxophones in 2008. I do remember it being an amazing thing, discovering video editing – I'd not felt such a sense of clarity and understanding around a medium since the pleasure of cross-hatching with a BIC biro as a kid.

Describe your experience with the tools you use. How did you start using them?

Laptop entirely. I've been through a few now, since my first white macbook. The intimacy afforded by a laptop – the sense of coincidence, of coalescence – inducted a kind of space that matched my rather distracted thinking and, really, alienation. Everything could happen in one place and at more or less the same time and on my own. Simultaneous production – a kind of super-positioning – seemed possible. I could write in Word while something rendered in Final Cut, something else converted in Streamclip, something else downloaded, something else uploaded, music played and video spooled – all in the same place. That sense of convergence has only increased over time. Pragmatically, things get pushed through one final cipher usually: Premiere these days for the videos; Indesign for the texts. But the work will have touched or been chiselled from, reduced by, whittled down using all manner of other bits of software and digital process. I've stopped using a camera – perhaps temporarily – relying solely on my laptop as the confluence and generator of everything. There are side effects, of course. I'm using Self Control at the moment. It's an app that blocks access to the internet for a given amount of time. It's effectively a pair of blinkers to funnel my concentration.

Where did you go to school? What did you study?

I went to Central Saint Martin's for my BA, and The Slade for my MA. Both in Fine Art – both places choosing the new media- / time-based media-esque 'pathway'. At Slade I'm pretty sure it was simply called 'Media', as apart from painting and sculpture; whereas at CSM it was called, amazingly, '4D', as apart from 2D and 3D. I was a four-dimensional student on my BA: I could pass through walls and stuff.

What traditional media do you use, if any? Do you think your work with traditional media relates to your work with technology?

Everything I use is pretty much a surrogate for some 'traditional media'. It's this surrogacy, this loitering analogous terrain that fascinates me, really. As distinct from more apparently 'experimental' techniques and methods. For example, my use of a Kinect is as a camera, is essentially visual – the structure being just that. It's about performance capture – to engage in a history of photography, performance, representation pretty much directly. Whereas it might be used elsewhere to, say, make a directly interactive EXPERIENCE. Which, ironic though it may be, strikes me as often far more trite, more apposite and agreeable a use of tech than a more sincere appropriative use. Not that that's necessarily what I manage, but to use the Kinect at its potential! To use it as a tool of productive progress. To align oneself to the desires of the technology, really, seems like something regressive regarding understanding the tacit ideology of such tech.

Are you involved in other creative or social activities (i.e. music, writing, activism, community organizing)?

I'd like to say I'm a writer of any worth, but I won't. Likewise music. These things, however, have managed to find a home in the videos, the books that accompany the videos. Or vice versa. But none of which are complete in the way that an insoluble poem might be complete – not until they're brought together, either in the combinative work of a video or in the combinative BRAIN of a spectator.

What do you do for a living or what occupations have you held previously? Do you think this work relates to your art practice in a significant way?

I'm a lecturer at Goldsmiths College in London. It's utterly related to everything I do – always has been. As in, I firmly believe in the education, even if I'm not entirely sure it believes in me, institutionally. It's a complicated and highly problematic scenario in the UK at the moment, but the grist of it – talking with students, discussing and getting mutually excited about things, is hugely rewarding.

Who are your key artistic influences?

There are some that seem so overt as to be plagiarism. A shortlist of debt and adoration might include Jan Svankmajer, Robert Bresson, Graham Lambkin, David Markson, Gilbert Sorrentino, Roberto Bolaño, Jeremy Prynne, Pierre Guyotat, Philip Atkins.

Have you collaborated with anyone in the art community on a project? With whom, and on what?

My dear friend James Richards is a constant collaborator – though only occasionally in a public sense. We worked together with Haroon Mirza in 2011 on an event for the screens in Times Square, which was where we solidified our friendship. The gallery I work with in London, Cabinet – Martin McGeown and Andrew Wheatley – is a constant source of terrific discussion, alcohol and intense camaraderie. My dear friend Patrick Ward, with whom I made the video 'Defining Holes', which was probably the most fun I've had making something. My partner Sally-Ginger has always been there, educating and encouraging me. 'Collaboration', however, in its particularly scary scare quotes, is something I sort of balk at. Only for myself, of course.

Do you actively study art history?

Yes and no. I am afflicted, like so many, with a post-internet dilettante approach. Not 'afflicted', as I don't see the problem in this specific context. And anyway, surely caution-inducing anxiety makes up for any guilt? There are parts of art history that are illuminated and others that are so murky as to be nearly invisible. Histories of cinema, music and literature similarly, though I'd say I'm more at home in those.

Do you read art criticism, philosophy, or critical theory? If so, which authors inspire you?

I do. Currently Catherine Malabou, Leo Bersani and Michel Serres are at the forefront of my addled brain. Literature usually wins out, however – though I'd consider all three of those writers to be literary in their aspect, if not in their… impunity.

Are there any issues around the production of, or the display/exhibition of new media art that you are concerned about?

The internet and its infinite cliques and fetish-holes. I still like rooms, (silent) communion, immersion – open-ish space. If only as respite and to get me away from this laptop here. I'm going to the toilet to be alone, etc.