Translation courtesy of Rachel Price.

![]()

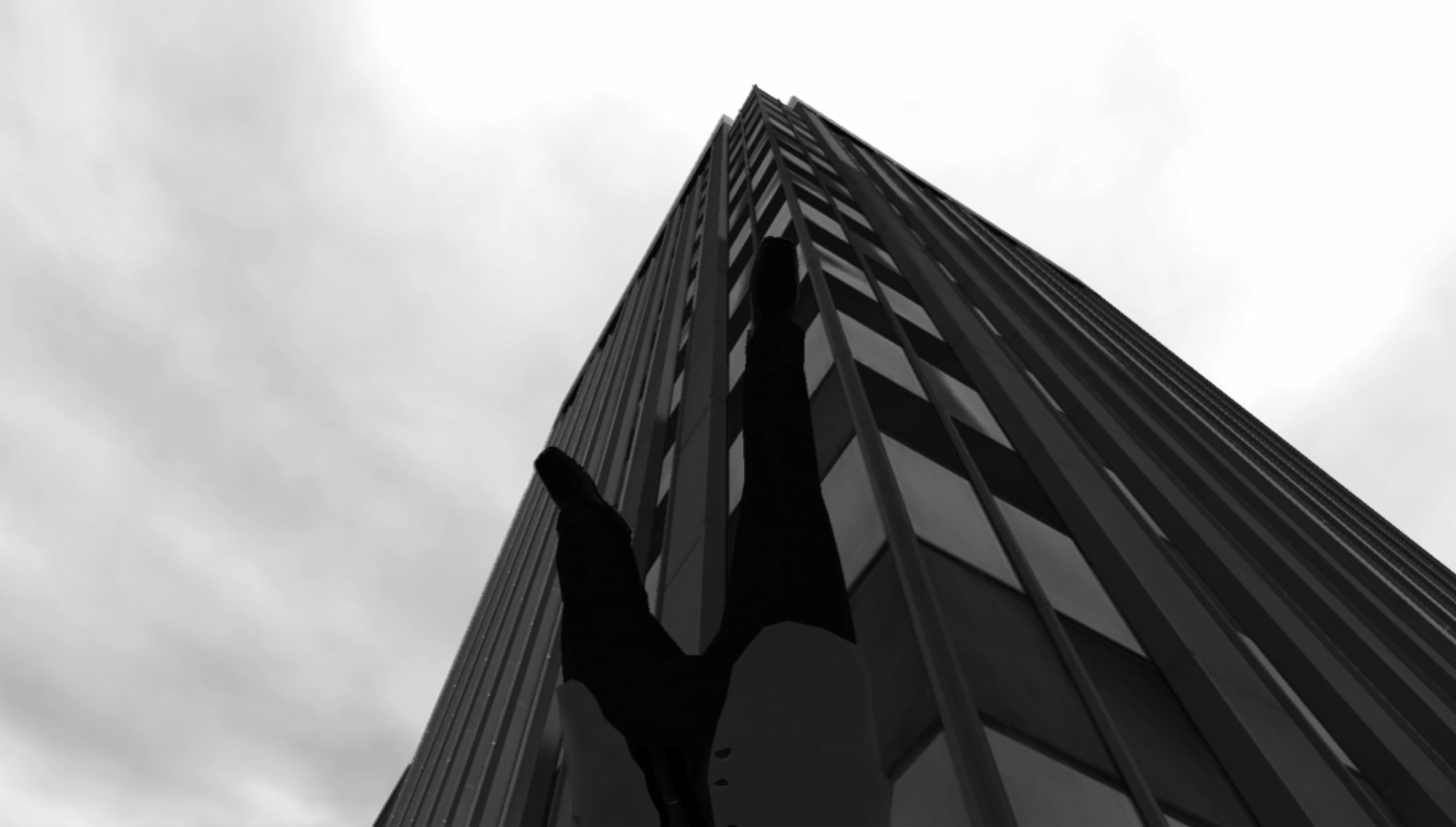

The Falling Man (2011)

Can you talk about your experience co-curating (with José Manuel Noceda) the Cuban Pavilion, Shared Creations, at the 11th Havana Biennial (2012)? What were your hopes for the mixed group of Cuban and international artists?

¿Puedes contarnos sobre tu experiencia en la co-curaduría (con José Manuel Noceda) en el Pabellón Cuba, Creaciones Compartidas, en la 11na Bienal de La Habana en el 2012? ¿Cuáles eran las expectativas para la mezcla de artistas cubanos e internacionales?

Working on the Biennial and learning alongside Noceda, Jorge Fernández and others was a very satisfying experience. My own art training was heavy on links to praxis; now, even when I'm involved in curatorial or theoretical work, it's hard for me to remove that filter. In contrast with other curatorial projects I've been involved with, on this occasion I was invited to be part of something that already had a structure and theme. Without the customary creative freedom, it became a learning experience, an apprenticeship. It’s also the first co-curation I've done, and the first curatorial project for which I wasn't myself producing something.

The Biennial is an international phenomenon. It's typical of such events that they increase relations between cultures, meaning artists come together who may have different ideologies and political and social discourses, but who are essentially motivated by similar tools and resources, from the market's most banal to the most spiritual of art. The mind constantly battles between a practical realism that trains its eyes on the external world and a search directed towards inner well-being, towards the idea of beauty and perfection. In all the big art events you find both states. In those moments, specific political relations are secondary.

Precisamente trabajar en la Bienal y aprender al lado de Noceda, Jorge Fernández y los demás, fue la experiencia más satisfactoria. Yo provengo de una formación en artes vinculada a la práctica, incluso aunque participe de una experiencia curatorial o teórica me es difícil distanciarme de ese filtro. A diferencia de otras curadurías que he realizado, en esta ocasión fui invitado a formar parte de algo que ya tenía una estructura y un tema; al no tener la acostumbrada libertad creativa, la experiencia devino aprendizaje. Por lo demás es la primera curaduría en dúo que realizo, y también es la primera curaduría en la que no tengo que hacer producción.

La Bienal es un fenómeno internacional. Es típico de la naturaleza de eventos de esta envergadura que se extiendan las relaciones entre una cultura y otra, esto implica la coexistencia de artistas que, aunque con diferentes ideologías y discursos políticos y sociales, están esencialmente motivados por herramientas y recursos similares, que oscilan desde lo más burdo del mercado hasta lo más espiritual del arte. La mente humana, constantemente, se disputa entre el materialismo más práctico que establece la mirada sobre un mundo exterior y una búsqueda dirigida hacia un bienestar interior, hacia la idea de belleza y perfección. En los grandes eventos que giran en torno al arte se encuentran concentrados ambos estados. En momentos como esos, las relaciones políticas particulares pasan a un segundo plano.

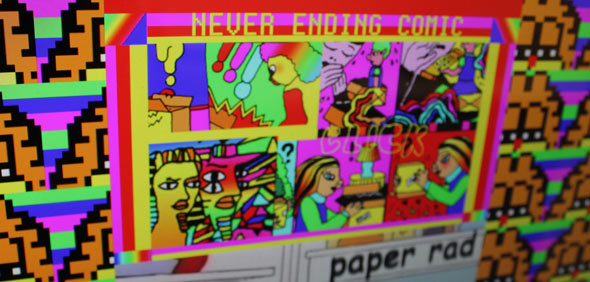

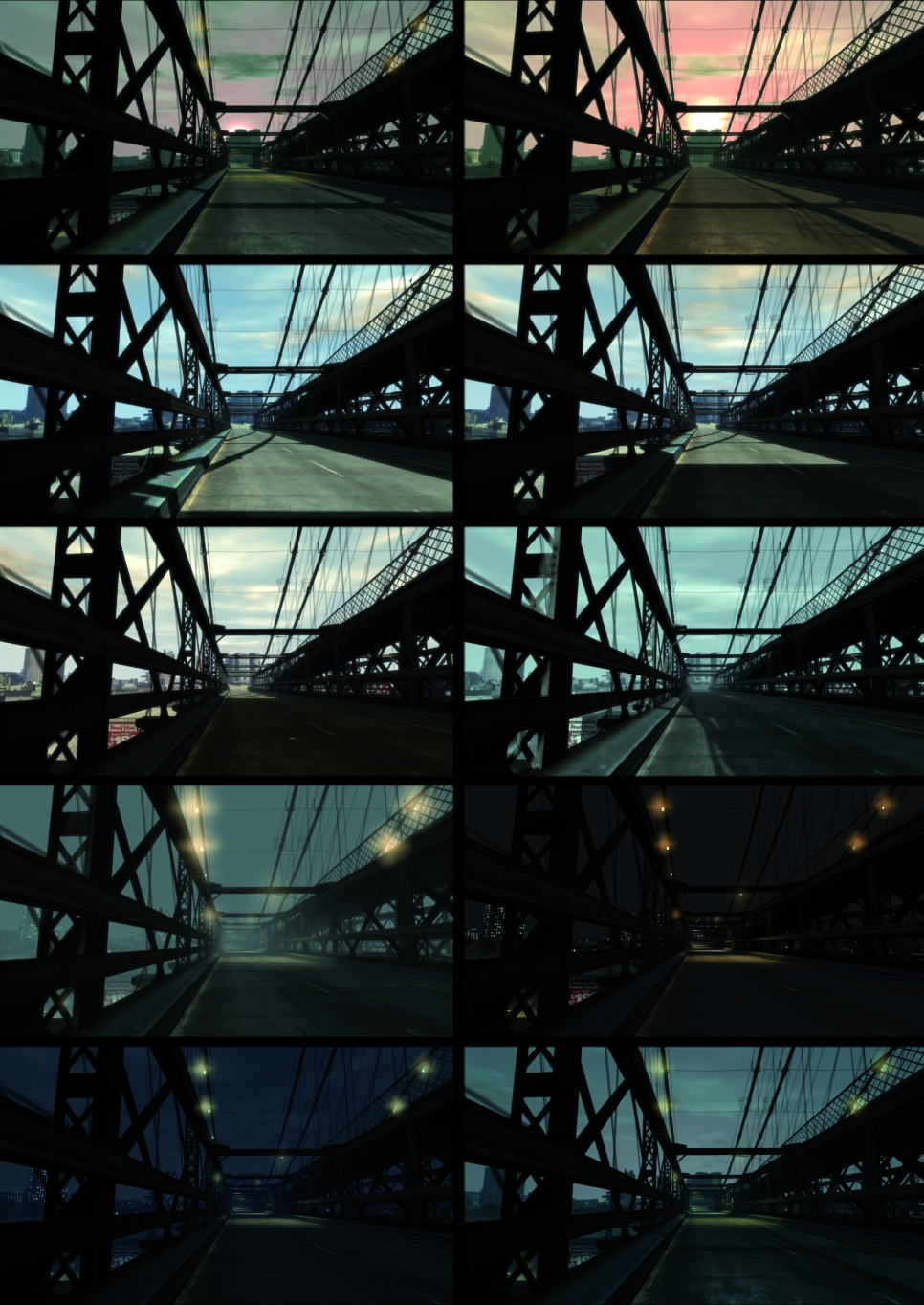

Your curatorial statement for that exhibition describes an attempt to find “communion between the works and the audience who moves from spectator to collaborator.” How does your own contribution, The Journey, a combination of video game code and existential reflections, use digital technology to blur of the lines of authorship and move towards a dialogical relationship with the spectator, particularly the broad international audience now in attendance?

Según tu opinión, como curador para esa muestra, describes un intento para “encontrar comunión entre las obras y el público que pasa de espectador a colaborador.” ¿Cómo tu propia contribución, The Journey, una combinación de códigos de video juegos y reflexiones existencialistas, usa la tecnología digital para hacer difusas las líneas de autor y moverse hacia una relación de diálogo con el espectador, particularmente la amplia audiencia internacional que ahora la aprecia?

The Journey is not a work that spectators can modify, play or manipulate; rather, it's a work that attempts to modify the spectator's perceptual point of view, through a basic concern: that of time. The Journey consists of a single image that is non-narrative and unchanging throughout the duration of the piece. It's less a passive projection of a machinima than an environment—ratherdreamworld-like, owing to the voice of the announcer and the music on the radio station, which I found on Liberty City. The work interacts with the spectator via two spaces: the real, which is where he hails from and believes he belongs, and the virtual, an apparently static image of one of the most transited bridges in the world andonecrossedundermuch stress; the path towards Manhattan, perhaps the most important artery for Western Civilization; empty, mute, and with a temporal compression of 24 hours into one. The spectator's mind lies between the two, observingboth sides and deciding which pill to swallow, the red or the blue. In this film, the character is time's movement itself and only needs from the observer her participation, her time; one second is enough. Observation itself is collaboration.

The Journey no es una obra donde el espectador pueda modificar, jugar, o manipular; más bien es una obra que intenta modificar el punto de vista de percepción en el espectador, a través de la fuente de sus preocupaciones: el tiempo. En la obra él solo puede encontrarse con una imagen que no cambia más allá del tiempo, que no cuenta nada, que no narra. En este caso no se trata solamente de una proyección pasiva de un machinima. Esta pieza es más un environment —yo diría que de una psicodelia minimal debido a la voz de la emisora y su música, que encontré en Liberty City—. La obra interactúa con el espectador desde dos espacios, el real, de donde proviene y a donde considera que pertenece, y el virtual, que representa el estado aparentemente inamovible de una imagen de uno de los puentes más transitados del mundo y, probablemente, el que con más estrés mental se recorre diariamente, el camino directo hacia Manhattan, quizás la arteria más importante para la civilización occidental; vacío, mudo, y con una compresión temporal de veinticuatro horas a una. En el centro queda la mente del espectador, observando a ambos lados y decidiendo cuál píldora tragarse, la roja o la azul. En esta película, el personaje es su transcurrir mismo y solo necesita del espectador su participación, su tiempo; con un segundo basta. Su observación misma es su colaboración.

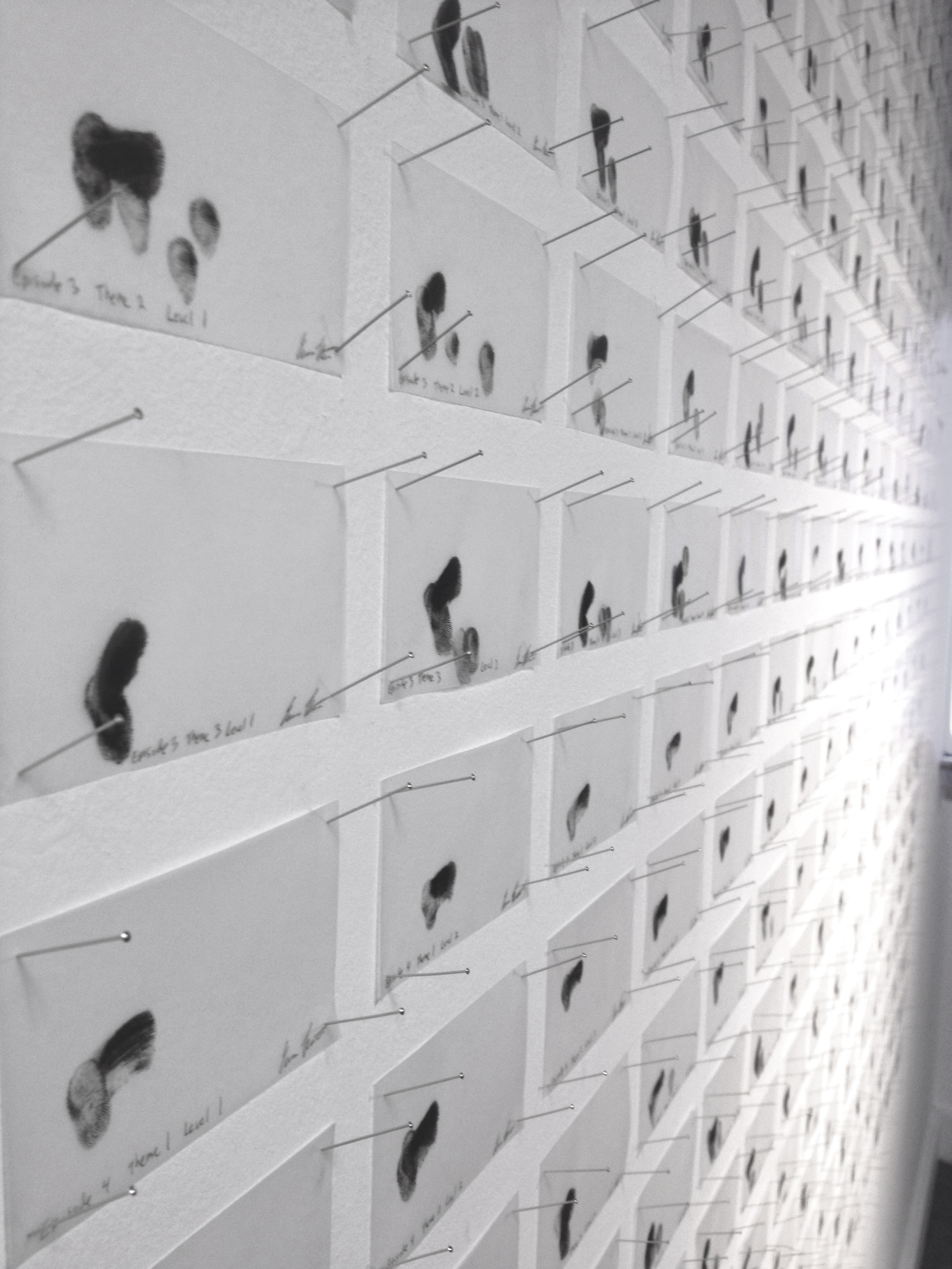

The catalog accompanying 2010’s “The Tipof the Bullet: A Decade of Cuban Art,” at the Cuban Pavilion (which you curated) has received attention and earned several awards. Can you talk a little bit about that catalog, for a show highlighting primarily emerging Cuban artists (many of whom were still in school at the Higher Institute of Art [ISA] at the time) and how you intended for it to function separately from the exhibition itself?

El catálogo que acompaña a El extremo de la Bala: Una década de Arte Cubano en el 2010 en el Pabellón Cuba, muestra de la cual fuiste curador, ha llamado la atención y recibido numerosos premios. ¿Puedes referirte brevemente a ese catálogo, como una muestra que destaca artistas cubanos emergentes (muchos de los cuales aún estudiaban en el Instituto Superior de Arte por aquella época) y cómo esperabas que este funcionara separado de la muestra misma?

In early 2000, Cuba created sixteen art schools, although the majority of those are not operational today. It was a moment in which schools were being built to train teachers, nurses, social workers, and art instructors; it was natural that art schools too should be built. Fidel Castro's dream of an educated society was realized as a society of permanent cultural training and development, closed in a time-space bubble, like a cyclic redundancy error.

That catalog came about in a moment whose generation the art world had not yet defined—a perverse mania of institutions, that need for definition—,in contrast withearlier decades of Cuban post-1959 art, often defined by their political and aesthetic tendencies. It seems humans only value what they can define, and our generation is turning out to be indefinable,since it is the result of many radical changes in the country, most spectacularly during the "Special Period" [1991-2010]; but our generation is also a product of the world of videogames, the internet and September 11.

Yet it is as if Cuban art history hadn't moved beyond 2000 and we—we alone—remain forever "emerging artists." As if our experience were insignificant and should be substituted by that of our predecessors. We needed a software to reveal to the collective conscious that cyclic redundancy error, the poor self-delusionthat ideological and aesthetic permanence can exist; because change alone is permanent. You can stop people, but a generation is unstoppable. Various kinds of software or viruses of this type appeared; that catalog is one of them, but I think at the same time it's singular, which gives it some importance.

The higher the level, the greater the error. The world needs a complete format of its culture. The internet helps in this respect: it helps dislodge from people’s consciousness the notion of discrete hegemonic cultural patterns, and reconstruct reality from a more holistic perspective.

Thanks to technology, and principally the internet, society doesn'tabsorb any absolute truth, but instead is bombarded by millions of truths collectively announcing that society's consciousness is but one piece of the trash sold to it and upon which it has grown too dependent. Whenwe begin to doubt these truths we begin to liberate ourselves from them. In the midst of this process cultural skepticism appears, a transitory phaseindicating change is happening within the generational consciousness. We're a skeptical generation, we're not interested in definitions; is there any other way to define us?

A principio del 2000, se crean en Cuba dieciséis escuelas de arte, aunque la mayoría no funcionan en la actualidad. Era un momento donde se construían escuelas de maestros emergentes, de enfermeros emergentes, de trabajadores sociales, de instructores de arte; era de esperar que se construyeran también escuelas de arte. El sueño de Fidel Castro de una sociedad culta, se concretó en una sociedad en permanente emergencia cultural, encerrada en un bucle de espacio-tiempo, como un error de redundancia cíclica.

Ese catálogo surge en un momento en que la institución arte no había definido esta generación —perversa manía de las instituciones— a diferencia de las anteriores décadas del arte cubano post-revolucionario, que están muy bien delimitadas por patrones políticos y estéticos. Parece que el ser humano solo le otorga valor a aquello que puede definir, y nuestra generación se tornó indefinible por ser el producto último de cambios muy bruscos en las estructuras sociales de un país, que tuvieron su ebullición más alta en el período especial; pero nuestra generación también es producto del mundo de los videojuegos, de internet y del 11 de septiembre.

Sin embargo, era como si la historia del arte cubano se hubiera detenido en el cambio de milenio y nosotros, solo nosotros, estaríamos emergiendo siempre. Como si nuestra experiencia fuera insignificante y debiéramos sustituirla por la experiencia de nuestros antecesores. Necesitábamos un software que sacara a la consciencia colectiva de ese error de redundancia cíclica, de ese pobre autoengaño de permanencia ideológica y estética; porque en el cambio mismo está la lógica de la permanencia. Se puede detener a las personas, pero una generación es indetenible. Creo que aparecieron varios software o virus de ese tipo, ese catálogo es solo uno más entre ellos, pero al mismo tiempo único en su tipo, otorgándole cierta importancia.

Mientras más alto es el nivel, más grave es el error, el mundo necesita un formato completo de su cultura, internet ayuda a ello, a remover de la consciencia de las personas la idea fragmentada de patrones culturales hegemónicos, y a reconstruir toda la realidad desde un pensamiento holístico.

Con la tecnología, fundamentalmente internet, la sociedad no absorbe una verdad absoluta, sino que es bombardeada por millones de verdades que le gritan que su conciencia no es más que una porción de la basura que le han estado contando y sobre la cual ha creado dependencia. Cuando la sociedad comienza a dudar de todas las verdades comienza a liberarse de ellas. En medio de ese proceso aparece el escepticismo a nivel cultural no psicológico; que no es más que un estado transitorio que muestra que se está produciendo un cambio en la consciencia generacional. Somos una generación escéptica, no nos interesan las definiciones; ¿existe otra marera de definirnos?

Your essay for that catalog talks about the role of information technology in conditioning this generation of Cuban artists in their aesthetic, political and social stances but also in their methods of expression. You call this a time of crisis, of “uncertainty, skepticism, myth and illusion.” How does this node linking contemporary Cuban society and virtual realities play a role in your own work? In a similar or different way than the younger artists featured in “The Tip of the Bullet?”

Tu ensayo para el catálogo habla sobre el papel de las tecnologías de la información como condicionantes de esta generación de artistas cubanos en sus posturas estéticas, políticas y sociales, pero también en sus métodos de expresión. Llamas a esto una época de crisis, de “incertidumbre, escepticismo, mito e ilusión.” ¿Cómo este nodo que relaciona a la sociedad cubana actual y las realidades virtuales, juegan un papel en tu propia obra? ¿Y en una manera similar o diferente, a los artistas más jóvenes presentados en El extremo de la Bala?

You’re quite right: it's all the same node. The same nodethat links contemporary Cuban art and virtual realities mediates between that work and my own. It's the samenode that mediates between other artists and their environment. It's a generational question. My work is just the reflection of my consciousness, which in turn is a refection of the collective consciousness of my generation, constitutinga kind of summa of historical consciousness; a collective memory in the form of chaos. The current generation of artists is just a handful of youth awakening from that insanity, or getting more comfortable with the luxury that comes with art: to continue dreaming.

Todo es lo mismo, ese nodo es el mismo que está entre la sociedad cubana actual y las realidades virtuales, el mismo que media en mi relación con el arte y con mi propia obra. También es el mismo que de igual manera media entre las relaciones de los demás artistas con su obra y su sociedad. Es un asunto generacional. Mi trabajo es solo el reflejo de mi consciencia, que a su vez es un reflejo de la consciencia colectiva de mi generación, que viene a ser la summa de toda la consciencia histórica; que es simplemente un recuerdo colectivo con forma de caos. Esta generación de artistas no es más que un puñado de jóvenes despertando de esa locura, o simplemente acomodándose al confort que vienen aparejados al arte, lo cual es seguir soñando.

![]()

The Journey (2011)

Age:

¿Edad?

According to the calendar, 35.

35 según el calendario.

Location:

Ubicación.

Physically, I live and work in Havana. In other ways I am anywhere.

Físicamente, vivo y trabajo en La Habana. Por lo demás estoy en cualquier lugar.

How long have you been working creatively with technology? How did you start?

¿Por cuánto tiempo has estado trabajando creativamente con la tecnología? ¿Cómo comenzaste?

For about 8 or 9 years. I always took seriously the notion that leisure is important for artists; the idea that the mind is most creative when it relaxes. There was a time when my art practice and my gaming were competing for my time and I had to choose between the two. So I kept on playing and justified it by turning it into art. I think it's the most beautiful justification I've come up with.

Unos ocho o nueve años. Siempre me tomé en serio eso de que para el artista es muy importante estar ocioso, cuando la mente cesa de preocuparse deviene su momento más creativo. Hubo un tiempo en que me competía hacer arte con el hecho de jugar videojuegos, me vi obligado a decidir por una de las dos prácticas. Así que seguí jugando y justifiqué el hecho de jugar, haciendo arte con ello mismo. Creo que ha sido la justificación más bella que me he inventado.

Describe your experience with the tools you use. How did you start using them?

Describe tu experiencia con las herramientas que empleas. ¿Cómo comenzaste a usarlas?

The term videogame is being called into questionby the very evolution of the medium. How then to define my experience with the related tools? Their expansion into automaticallygenerated interactive systems, simulators, software for physical and mental rehabilitation, programs for military training, educational programs—all of the same nature as video games—makestheir definition imprecise. I also can't even be sure, in my own practice, whether I'm making art, studying, playing, doing politics or simplywasting time, or whether I'm experiencing other zones of perceptual reality, a zone of consciousness built upon what we perceive and which we grant the category of the real.

I began using the tools the same way almost all Cuban children did at the time: pestering my mother to rent me an Atari from someone in the neighborhood. After studying art a symbiosis happened. Now I continue with my computer and my experience is that of someone from the digital age, but my mother thinks I've never grown up and I'm still playing an Atari.

El término videojuego está siendo cuestionado por la evolución misma de esa manifestación, ¿cómo puedo entonces definir mi experiencia con ellos? Su propia expansión en sistemas automatizados interactivos, simuladores, software para rehabilitación física y mental, programas para entrenamiento militar, programas educativos —todos de la misma naturaleza que los videojuegos—, hacen que su definición sea imprecisa. Por otra parte, en el hecho mismo de mi experiencia no puedo definir si estoy haciendo arte, estudiando, jugando, haciendo política o simplemente perdiendo el tiempo, ocioso, o si estoy experimentando otras zonas de la realidad perceptiva, esa que se construye en la consciencia a partir de lo que percibimos y le otorgamos categoría de real.

Comencé a usar estas herramientas como casi todo niño cubano de ese entonces, martirizando a su madre para que le alquilara un ATARI en el barrio. Luego de los estudios de arte se produjo una simbiosis. Ahora sigo con el ordenador y mi experiencia es la de alguien en la Era de la electrónica, pero mi madre considera que nunca he madurado y que aun sigo jugando con un ATARI.

Where did you go to school? What did you study?

¿A qué escuela asististe? ¿Qué estudiaste?

I went to a beautiful ruin of an art school that used to exist—it's no longer the same—in Trinidad, a town I recommend to anyone visiting Cuba. A school that, givenits conditions at the time, could well have been a rural school somewhere in Africa—according anyway to [art critic Gerardo] Mosquera, as he described in it his first and only visit in '98. I was just beginning my first year of studio and I still dreamed of painting like Rembrandt and so on. But I had the chance to go to a magisterial talk on the work of Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Imagine, I never recuperated from the shock; it forever would mark my experience of art.

A una demacrada y preciosa escuela de arte que había antes —digo que había porque ya no es la misma— en Trinidad, un pueblo que le recomiendo a todos los que visiten Cuba. Un colegio, que debido a las condiciones en que nos encontrábamos, parecía —según Mosquera— una escuelita rural de alguna zona de África, como lo definió a raíz de su primera y hasta ahora única visita en el ‘98. Yo estaba apenas comenzando mi primer año de estudio y aun soñaba pintar como Rembrandt y cosas así. Pero tuve la oportunidad de asistir a su conferencia magistral sobre la obra de Felix Gonzáles-Torres. Imagínese, no me recuperé jamás de ese choque, marcó para siempre mi experiencia con el arte.

What traditional media do you use, if any? Do you think your work with traditional media relates to your work with technology?

¿Qué medios tradicionales empleas, si es que lo haces? ¿Crees que tu trabajo con los medios tradicionales se relaciona con tu trabajo con la tecnología?

They're both resources that I use for making an idea into an object, phenomenon, fact or experience. Art is an attempt to express the inexpressible; to define it is to limit it. When youset out to study something it becomes isolated and closed in on a concept and direct experience is lost. In this century it's increasinglyhard to find artists defined by a single medium, apart from those who do it for reasons related to the market. I'm not committed to a specific medium or genre, I'm rather interested in working with cultural, conceptual, scopic, social, political concepts, all linked to the act of living in a context in which there is limited training in perception.

Tanto lo uno como lo otro son recursos que utilizo para que una idea encarne en un objeto, fenómeno, hecho o experiencia. El arte es un intento de expresar lo inexpresable, definirlo no es más que limitarlo. Qué se hace con todo lo que se pretende estudiar, se aísla y se encierra en un concepto y eso produce que se pierda la experiencia directa. Cada vez es más difícil en este siglo encontrar artistas definidos por un medio específico, aparte de los que lo hacen por cuestiones relativas al mercado. Yo no estoy comprometido con medios o géneros específicos, más bien estoy relacionado a procesos culturales, conceptuales, escópicos, sociales, políticos; vinculados todos con la acción de vivir en un contexto con un limitado entrenamiento de percepción.

Are you involved in other creative or social activities (i.e. music, writing, activism, community organizing)?

¿Estás relacionado con otras actividades creativas o sociales? Por ejemplo, música, escritura, activismo u organizaciones sociales.

Some writing, I still can’t find a way into poetry, at least in its strict written structure. Eventually, work on an electronic music project (Rezak), with the idea of exploring the adjacent zones between sonorous and visual universes.

Algo de escritura, todavía la poesía me excluye, al menos en su estructura tradicional escrita. Eventualmente trabajo con un proyecto de música electrónica (Rezak), con la idea de explorar zonas colindantes entre el universo sonoro y el mundo de la visualidad.

What do you do for a living or what occupations have you held previously? Do you think this work relates to your art practice in a significant way?

¿Qué haces para vivir o qué ocupaciones previas has tenido? ¿Crees que se relacionan con tu práctica artística de un modo significativo?

I don't create to live, I live to create. The nature of what I do is life itself, I don't need more. Everything is related. I can only say: some things, like art, I do out of love, others just for money.

Yo no hago para vivir, yo vivo para hacer. La naturaleza misma de lo que hago es el hecho de vivir, no necesito más. Todo está relacionado. Yo solo puedo decirle que algunas cosas como el arte las hago por amor, otras simplemente por dinero.

Who are your key artistic influences?

¿Cuáles son tus influencias artísticas fundamentales?

I never like getting thatquestion, because it leads me towards an endless series of potential answers I always end up abandoning. There's no difference for me between seeing a movie, going to the theater, reading a book, playing a video game and the daily experience of life; from all of those come an infinity of influences. I can answer more precisely quoting Whitman: "These are really the thoughts of all men, in all ages and lands, they are not original with me."

Esta es una pregunta que no me gusta que me hagan, me conduce a un pensamiento interminable, que siempre debo abandonar. Para mí no hay diferencia entre ver una película, ir al teatro, leer un libro, jugar un videojuego y la experiencia diaria de la vida; de todo ello provienen infinitud de influencias. Puedo responderle con más exactitud citando a Whitman: Estos son realmente los pensamientos de todos los hombres, en todas las edades y tierras, no son originales míos.

Have you collaborated with anyone in the art community on a project? With whom, and on what?

¿Has colaborado con alguien en la comunidad artística en un proyecto? ¿Con quién y en qué?

Everything I do is a collaboration, though because of geopolitical circumstances the structure of the collaboration can be a bit limited; still, one can't corral the intangible. That structure might be called love. Every moveI make is motivated by it; when it’s done, the whole universe has collaborated in it.

I've coauthored work with other artists, especially NaivyPérez. I'm currently collaborating with the artist María Magdalena Campos-Pons, whom I consider a godmother more than a mentor, for her generous efforts to support emerging Cuban art.

Collaboration is of course also essential incurating, and in that sense I've worked with artists whom I admire such as Vuk Cosic, Olia Lialina, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer; in the exhibition Un mundo feliz [A Happy World] and in the context of the 10th Havana Biennial (2009).

I'm currently working with Liz Munsell—of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston—on curating a show called Cuban Virtualities, proposed for fall 2013 at Tufts University; I may myself be in Boston at that point studying towards a Masters in 2013 at the Museum School.

Colaborar es todo lo que hago, aunque por circunstancias geopolíticas la estructura de esa colaboración se ve limitada, pero no se puede contener lo intangible. Cada gesto que realizo está motivado por el amor, al hacerlo, el universo entero colabora en su realización.

Tengo obras en coautoría con otros artistas, especialmente con Naivy Pérez. Actualmente colaboro con la artista María Magdalena Campos-Pons, a quien más que mentora, considero madrina, en su generosa iniciativa de potenciar arte cubano contemporáneo emergente.

El propio hecho de hacer curadurías me ubica en un punto en el que la colaboración es esencial, en ese sentido he trabajado con artistas que admiro, como Vuk Cosic, Olia Lialina, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer; en la exhibición Un mundo feliz, en el marco de la Décima Bienal de La Habana (2009).

Actualmente trabajo en coautoría con Liz Munsell –del MFA de Boston–, en una curaduría titulada Cuban Virtualities, que debe realizarse en el otoño del 2013 para la Tufts University también en Boston, ciudad con la que estaré muy ligado, ya que, posiblemente, comience estudios de maestría en la SMFA.

Do you actively study art history?

¿Estudias activamente la historia del arte?

If by studying you mean reading books and essays and histories of art, Hauser, Gombrich, Greenberg, Danto, encyclopedias, internet, seeing documentaries, movies… then no, I don't. These activities become a part of daily life, like sex, eating, drinking, etc.Reading and writing are, like making art, forms of sharing. As long as the history of art continues to be seen as a tale, there will be people who need to study it.

Si por estudiar se entiende leer libros y ensayos de historia de arte, Hauser, Gombrich, Greenberg, Danto, enciclopedias, internet, ver documentales, películas... entonces no la estudio. Estas actividades devienen parte de la vida diaria, como tener sexo, alimentarse, embriagarse, etc. Yo participo de una experiencia de la cual escribir y leer, así como hacer arte, son algunas formas de compartir. Mientras la historia del arte se siga viendo como un relato, habrá quien necesite seguirla estudiando.

Do you read art criticism, philosophy, or critical theory? If so, which authors inspire you?

¿Lees crítica de arte, filosofía o teoría crítica? Si es así, ¿qué autores te inspiran?

Well, I've gotten a lot of pleasure reading certain authors. If you asked me for a list of favorites, right now I'd say Voltaire, Borges, Hesse, Mann, Eco, Benjamin, Barthes, Virilio, Baudrillard, Danto, Foster, Pessoa, Khayyam, Leonard Cohen, Krishnamurti...

Bueno, he sentido mucho placer leyendo algunos autores. Si me pides un "top", ahora diría que Voltaire, Borges, Hesse, Mann, Virilio, Benjamin, Baudrillard, Danto, Foster, Pessoa, Khayyam, Leonard Cohen, Krishnamurti...

Are there any issues around the production of, or the display/exhibition of new media art that you are concerned about?

¿Existe algún tema relacionado con la producción o exhibición de los nuevos medios artísticos que te preocupe?

There's a real explosion of such work these days and I think there are some who have become snobs about it. People tend to confuse an artwork with its effects and visual spectacle. I also see a lot of nostalgia for modernity and people who wish to reduce artistic practices to limited interests tied to politics, the market or specific genres; but none of that really concerns me. Since the King has always needed entertainment, in all societies one finds buffoons.

Considero que existe una efervescencia en estos momentos y se ve mucho snob por ahí. Se tiende a confundir obra de arte con efectos y espectáculos visuales. También veo que hay mucha nostalgia por la modernidad y hay quienes intentan reducir las prácticas artísticas a intereses limitados relacionados con la política, el mercado o géneros específicos; pero nada de eso me preocupa. Debido a que el Rey siempre ha necesitado diversión, en todas las sociedades han existido bufones.