![]()

Throughout this guide I’ve tried to isolate the patterns of how we think about the Future-Present, as symbolized by particular evocative technology. By engaging five, extraordinarily knowledgeable informants, I’ve traced their thoughts into directional arcs that don’t necessarily nail down this swirling cloud of future-forward ideas, but at least give us sense of the difficulty of the terrain.

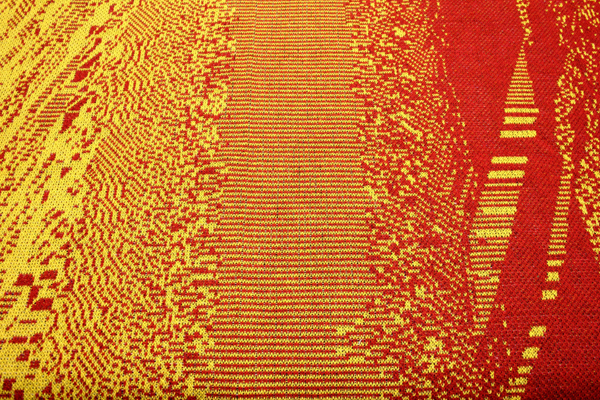

The archetypes are stories, each one about us, our ideas, and our material world. The excitement of the future is represented by the LED. Neodymium magnets tell a story about the the allure of technological magic interacting with our everyday life. The fable of the cyborg explains a bit about our interface with our own history. The theology of our technologically advanced commodities are explained to us through drones. And our maps tendency to glitch is a cautionary tale about our minds’ inherent difficulties in navigating all of these different idea structures at the same time.

I like to think of these archetypes as stories, because there is something harmless in allegory. A meaning is intended, but if it doesn’t particular stick, or if as storyteller I trip in my delivery, the stakes are low. These are not actually designs for massive structures, harnessing dangerous physical forces to be constrained within conduits wrapped around us while we sleep at night. If these narratives become unpleasant, we can simply wake up, dispelling them like a dream, returning to the safe world of consistent reality that is not fraught with loops of meaning and pitfalls of symbolism. We can clear the slate easily, claiming the fallibility of narratives, and returning to the kernel of “simple” material things, ignoring the implications of our ideas. And then the next night, we have a chance to dream again.

But what I have come to realize is that stories are not a low impact art. True, any particular essay about the future might be ignored, deemed to be of little use or effect, and sent to join the vast quantities of cultural product that collect upon the roadsides of the networks, like so many bottles and cans without even as much value as a token deposit. But the effect that a narrative can have is extraordinarily real. Those roadsides are not only avenues of amusement, but also the pathways of history. What is the worth of a narrative when the climate of the world is at stake? What is its value when could a commonly told story result in the use of a catastrophic weapon, as opposed to only its development? What is its currency, when an implicitly understood fable forms the boundaries of a person’s lifelong torment, or pleasure?

We have a limited time to shape these potentially-valuable/potentially-worthless stories because our technological history is unfolding, not in the future, but immediately. And we have very few means for judging history’s effectiveness. As much as we think about the strengths and functions of any particular narrative, there is no way to be aware of every vulnerability. There is no such thing as surety, when it comes to narratives. There is only ever our best guess, and our endless capacity for second-guessing it.

![]()

The narrative of criticism of the Future-Present, in all its difficulties and cultural diffuseness, is the story of the last archetype: the “zero-day”. The zero-day is a particular sort of software or other system vulnerability, named sometime in the mid 1990s as the sharing of knowledge between technicians sought to focus on vulnerabilities previously unknown, and therefore more important. Hunted by developers and hackers alike, the zero-day is not just a weakness of a designed system, but a weakness held and stockpiled, a “secret weapon” of sorts for exploiting that system in the right or wrong hands. Unlike the known vulnerabilities that are patched over with security updates, there are “zero-days” of warning about these particularly strategic exploits, and defense against them is difficult to impossible. When used in an attack on a system, those who would defend that system are caught unaware of the weakness. Depending on the severity of the exploit and the system it invades, the value of a zero-day can run into the millions of dollars, as in the hands of either the attacker or the defender, it could represent the difference between maintained security, or complete compromise.

While it is obvious that the vulnerabilities of any sort of system, technological or otherwise, will always be hunted down, that this particularly strategic exploit would be classified, commodified, and cultivated is perhaps a little surprising. That there would be an industry devoted to not just taking advantage of systems, but of finding the best way to utterly destroy their trustworthiness, is not just a cynical fact of the human species, but speaks volumes about the way our society has come to exist.

But that is also what this series’ theorizing of the Future-Present is intended to do. Whether we think of ourselves as wearing white hats, black, or some shade of grey, we are trying to not only figure out where things are going, but looking for the holes in the system that will inevitably result. We call this criticism, and we may do it for fun, for a cause, for pay, or all three. It is a bug and a feature of our society that while some may be enamored by narratives of progress, success, triumph, and heroism, others will cultivate narratives of dystopia, cataclysmic failure, slow degradation, and outright villainy. Humans will experiment with vulnerabilities--not only as a minority report, but to be part of the system. The holes in the optimistic narratives are not empty, but filled with a certain thriving rot. This decay is the undercurrent, the living strata of the reverse of the system, the microflora and humus necessary for growth. A strong culture of criticism is vital.

How do we use these theory exploits? Do we stockpile them, like zero-days, waiting to take our enemies unaware? Or do we sound the alert? Depending on the system, an argument could be made that either behavior is ethical. In the theory business, we tend to think that open discussion of ideas is best--but given the stakes of the Future-Present, we also might be tempted to keep our cards close to our vest. Is it unethical to sell theory exploits? Maybe, if they would better help more people if they were free. But what if their value could support further theory development and discover more exploits? All of these ethical issues are underscored by the question of value. If we cannot tell the value of our theory narratives, it is difficult to understand whether there is an ethical implication at all. The lasting effect of using or not using something with an unknown value or lack of value is almost impossible to measure. Unlike zero-days, the market for criticism is not measured in quantitative value. The critical narratives of Future-Present system failure are uncertain, un-valueable, indistinct, and outside of a quantitative metric of efficacy.

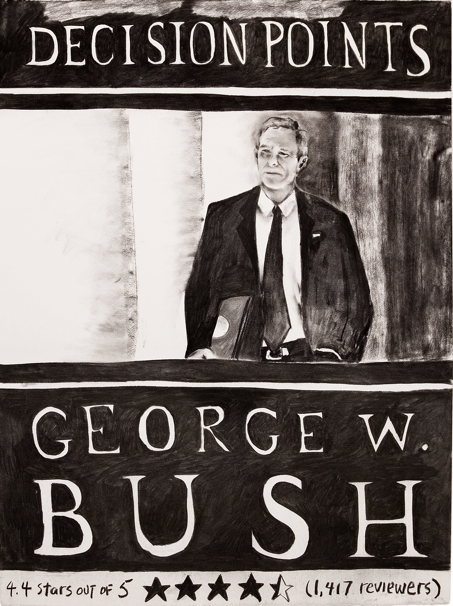

The problem with the humanities is that it is good at criticism, but bad at effects. It isn’t good at doing things in the world. You could argue that someone leaving comments on an Amazon camera review has more impact that Fredric Jameson. Someone writes a review, and supply chains kick into gear, engineers work overtime, quarries are taxed to produce minerals--these are global geologic effects. I mention this because this is opposed to what we think of as “criticism” in the humanities. I have mixed emotions about academia and working within it. Opposite to that, we get people like Mike Daisey’s Apple dialog, which had issues with fact-checking. And yet it cataloged an intense scrutiny on Apple and engendered a review of their hiring practices. Tim Cook actually went to Foxconn. It’s hard to say that he went there because of Daisey, but Daisey’s performance had real life effects, in the way that a blogger might not have had.

I think there’s a potential to have criticism that has an effect on the way things are made. I think that’s why a lot of people are experimenting with fiction, because it allows things to reach people in a way that it wouldn’t if you wrote for a Marxist criticism magazine or the University of Chicago. It’s a nice way to reach a larger audience. I think there will be things like Mike Daisey’s plays that hits at the right time, and affects the supply chain. I’m inclined to think that it will happen through the humanities, but not in academy. Jason Kottke can probably affect Apple’s development more than the academy can. I generally believe more people in academia should embracing things like blogging to find a wider audience for criticism. I’m still slightly amazed when people cite Kottke as an academic source. If you could take the populist appeal of Gizmodo and apply it to criticism, I think that would be an exciting use of social media. We could intensify the social media discourse by adding really exciting ideas to things considered speculative or frivolous.

— Geoff Manaugh

![]()

There is certainly a degree of obligation for society to monitor and regulate technology. Technology is not solely an independent sphere of immanent becoming that leaches into our reality. We intuitively understand this knowledge and have curated and shepherded technologies since the dawn of time. We suffer collateral damage, but the general trend has been to contain the existential threats offered by our tools. For example, we have not yet destroyed ourselves in nuclear conflagration.

Our security, however, is surely not a given. It is only our vigilance and the insistence on a degree of political representation for the shared values of culture & community that mitigates the threat of our creations enough to ensure progress. At present, we do not fear governors so much as potential world destroyers. It is now rogues we worry about--those who have removed themselves from culture and placed themselves above politics. So while it is our obligation to ensure that technologies do not destroy us, it is also our responsibility to innovate technologies that will equalize the balance of power across civilization.

— Chris Arkenberg

New methods of criticism are always coming online, says Geoff. As the system evolves, so does its holes, and so does the methods of finding them. It does seem that there is a certain vigilance in society for keeping watch over our mechanisms, and for correcting mistakes before they have far-reaching effects. This tendency’s successes are proof of its own efficacy. However, as Chris notes, there are trends to this instinct that may leave the search for vulnerabilities vulnerable. Working on instinct is not a theory, but a baseline reflex.

We have this cycle between society and technology--they affect each other. Groups, corporations, or communities, are the actors here. They inflict technology upon everyone else, and this changes the shape of the world for everyone else. This should probably be disturbing to us, as this is the dynamic that we’re stuck with. Those emergent actors aren’t any more rational than individuals are. We see corps lashing out for their own survival, and creating things like the DRM system. They are scared, and creating a thing in response. Those actors might be more rational than individuals, but certainly aren’t necessarily so.

People do have some agency over technology, but it is constrained by other forces. The agency of technologists only goes as far as creating the technology. Society decides what they do with it. Technologists can’t take technology out of culture, once it is inserted.

I’d like companies to be more conscious of this. I think it would be a better world if technologists paid attention to the harm they are doing to the world. But there is no incentive to do this. It is practically a losing battle to get people writing software expressly for non-profit or activists causes to properly consider the impact of their technology. Oil companies? Forget it.

—Eleanor Saitta

It would be nice to think of criticism as a contrary force to the less positive aspects of the capitalist system and its valuations. We’d like to think of criticism as objective, above instincts such as self-defensiveness and greet, impartial to all concerns except ethical. But while criticism can identify positives and negatives objective from capital, these create new feedback cycles that are not economic, and yet keep theory trapped in subjective, biased instinct. The motivations of profits and loss are only one valuation system that competes with ethics for constructing the narratives of technology.

The normative structures and goals of culture define the terms within which power relations are expected to operate. Politics is inevitably an expression of culture, even if representation may drift towards elite sub-classes.

As an expression of mind, technology contains all the same desires and fears and psychic baggage as anything we do. Some technologies may be aspirational while others are intentionally destructive. Some technologies may indeed be effectively neutral but all are colored by the goals of their creators. If a technology shifts the power dynamic, then the technology becomes political, whether by intent or serendipity.

— Chris Arkenberg

Are their schema-less technologies? Probably not. I’m a firm believer in the statement, “technology is neither good or bad, nor is it neutral.” Tech isn’t about social structures, but of course it also is. Our “normal” society is western, male-dominated, etc. So this is also what technology “is”. The assumption is that straight white men use technology in the “right way”. If you aren’t using tech in the same way as the dominant culture, you’re doing it wrong. See, for example, the endless news articles about how much teenage girls use SMS, or how teenagers are postponing getting their drivers’ licenses. Not to sound all feminist theory 101, but to assume that there are technologies that are schema-free, you are deluding yourself. To say that technology is available to everyone, you’re deluding yourself. The faces of “The Singularity” are all older white men. That’s not a coincidence. Bruce Sterling said this better than I can, in his SXSW 2012 talk– that life extension is going to mean a cohort of Sarkozys and Berlusconis, hitting on twenty-year-olds a century their junior. If you are brown, or female, or queer, you know something about how your body (and how other people respond to your body) affects your psyche and identity. Only straight, white, able-bodied males think that their body doesn’t affect their brain. So if you talk about uploading your brain, you are talking about an unmarked body. That’s an example of a tech that is presented as not about society, not about schemas, but that isn’t true.

I think its even more true now than it’s ever been, that people are starting to think about why we do things. Why do we have the government that we have, why do we have the capitalist system in the form we do... all these cultural assumptions are being questioned. This is the culture we’ve lived in, that we’ve accepted, but now people are not sure they’re happy with that anymore. Do we want our culture to only be what is sold to us?

— Deb Chachra

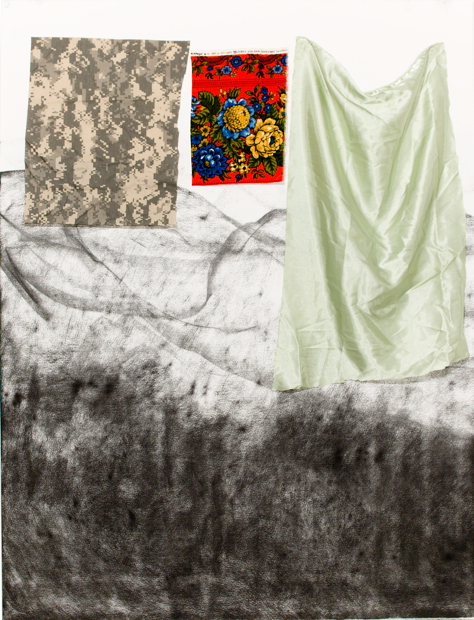

The stories that we tell as a means of technological criticism are ultimately, about ourselves. We are a technological species with a sprawling culture of signifiers both right and wrong, helpful and harmful. We are critically minded individuals, that despite all that we have done to the earth and its pre-existing systems, still cling to a notion that we are ethical creatures, deep down. And also, these are narratives about our self--our sense that we are material beings, that interact with the world in a curious, inventive, and creative way. We want to do the right thing--whatever ideal that might be; and we want to build things--whatever material object those might be. We are both the strength of the system, and the vulnerability of its holes. Between these two, in the process of navigating the difference, is what it means to be human: what has meant in the past, what it means today, and how we think the endless cycles of more “todays” will affect it all. Both Chris and Bruce come back to drones to describe this composite humanity. Drones are the Future-Present archetype for the commodified technological symbol: the singular abstracted entity for vast cosmologies of systems, meanings, and materials. Perhaps what is most uncanny about them, is that these are incredibly non-human objects, that could not have been made by anything other than humans.

I have a deep curiosity about how the self is constructed, how we define our own agency within a web of interdependencies, and how our technologies modify and extend our sense of self. So in this context, drones are fascinating as disintermediators of presence enabling both remote viewing and remote aggression. The drone is symbolic of our ability to extend our senses beyond our corporeal containers, made most compelling as an object of flight. Thus, we become the bird of prey, conferred with a sort of shamanistic projection through this technology.

Culture will attempt to contain powerful technologies in ways that align with its goals and defend its progress into civility. Thus, biology presents the core argument for or against technology: does it help me or hurt me? Culture contextualizes the technology within the social, moral, and ethical spheres: is this good or bad for society? And politics evaluates the role of technology within management structures, resource requirements, and inter-tribal dynamics: Does it help the stakeholders committed to the goals of the majority power bloc?

There are no politicians who are not a part of culture. And there are no earthly technologies that are not expressions of humanity.

— Chris Arkenberg

There's tremendous energy in the DIY drone scene. They're just cellphones with wings, they're not as remote and forbidding as the Manhattan Project. Weird cheap atelier drones are proliferating fast. There is a ton of action in the drone space. The editor of WIRED US does practically nothing else.

Actually, drones are a cheap globalization hack. They're a way to put a virtual military presence on the spot without formally invading a nation-state and crossing its land-boundary casus-belli tripwire. If you start politically construing drones as an unalloyed political badness that inherently lacks any toy-balloon factor, that's a weak political analysis and untrue to historical experience with similar military technologies. Better to confront drones as what these devices really are, component-wise, capacity-wise, and don't construe them as Super Mario.

I'm all for political analysis, sort of, but if I were you, I'd hearken back to the historical reaction about mainframe computers: "they're for IBM, they'll spindle and mutilate all the good people". Or the ARPAnet: “it's from defense spooks, it'll spindle and mutilate all the good people." Drones are getting a free ride because the population's convinced that the people being spindled and mutilated are the terrorist-bad-people. We've been round that tech-proliferation carousel before.

I don't believe there's such an entity as an absolutely beneficial SF concept. "To the unclean mind nothing can be clean." It’s not an either-or issue. Drones aren't particularly efficient human slaughtering machines in any sense. Even the people most into the development arc of lethal drones are trying to make them efficient assassination machines, not efficient weapons of mass genocide. We already have efficient weapons of mass genocide.

I don't much care for the dictum that speculation needs a purpose in action. This kind of non-whimsical use-value argument is like the school of East German design. No toys allowed in your discourse? No thought-provoking curios? No surprises, no sense of wonder? Take a hike!

There's more at stake than the fates of "our" intriguing little projects and "our" little technological dalliances. We don't live in a world alternatively divided between Luddism and Cold War Skunk Works. Both those things have been dead for decades now.

Every cult's impetus to tinker is always being co-opted by some X. You need some intellectual generosity here. You can't virtuously do nothing with your lifespan because your every effort might be repurposed as a bayonet or a deodorant ad.

Also, if you "pledge allegiance" to something, what's the big scary downside that seems to be bothering you there? Are you afraid someone will laugh, somehow? That's rather a paralytic burden of dignity, isn't it?

— Bruce Sterling

The vastness of speculation, of criticism, and of narrative, is the overarching stimulus that snaps me out of the paralytic burden. Whether we identify central critical questions to define a technology’s ethicality or not, there is no escape from the interdependent network of shifting narratives. Every Future-Present Archetype I have identified could be pushing the wrong argument. This guide, as a topology of narrative arcs, could be outdated and insufficient in a matter of months, if it ever was useful. But what keeps the blood pumping through my writer’s veins is that critical archetypes will continue to emerge. Every day that passes, every stunning idea and technology that we hear about, every horrifying outcome of the human species, and ever point at which we pause, uncertain and unsettled, will be the underlying terrain of these stories. And this will be the space through which we’ll either understand our lives, fail to do so, or more likely a bit of both--now, and going forward.

![]()

UCSD robot mouse.

When attempting to map out the Future-Present, there is not just one map to consider; there are three. These three categorical types of map—our mental maps, symbolic maps, and broken maps--are each a schematic layer in our effort to perceive the world, and it is in their dissonance that the world actually exists. We must identify not only what these maps are, but what they are when they fail. In the fractures, one sees the spidering web of weaknesses, the many possible scenarios of rupture that select without warning. Reality is unpredictable, bursting from its constraining archetypes. And yet it is uncannily similar to all the breaks we’ve seen before, like a river delta resembling a tree.

The first category of map resides somewhere in the brain, perhaps in the hippocampus. It is through these networks that our neurology gives us a sense of space that we might try to express, record, and share with others. In studies performed on mice, “place fields” have been identified in their hippocampal neurons. Everytime the mouse passes through a particular known place in its terrain, a burst of action potential fires through the same neurons. We know less about the human brain, but it is clear that our hippocampus is important to forming memories, and that larger hippocampi correlate with people who have more detailed place knowledge, London cab drivers, for example. Somewhere, lurking inside the chemical differences between the inside and outside of neurons, in the minor voltages and in the ever-changing and evolving cell pattern of our neuroanatomy, is a material record of what we mean when we sense our geography. We cannot read this map— we can only think it. We express this map’s imperfections via our senses. When this map fails, we feel lost.

![]()

The second map is spoken aloud, in the possibility of uttering a symbolic map. Humans are never content at forming schema and just keeping them to themselves. Our schemas are meant to be shared, explained, inscribed, and signified. But the topology of these symbolic maps are as complicated and multifaceted as our neurology. It was Alfred Korzybski who constructed the phrase so relevant to our contemporary times, as the second part of a statement first spoken in 1931:

A) A map may have a structure similar or dissimilar to the structure of the territory...

B) A map is not the territory.

One of the primary tenets of Korzybski’s theory of general semantics is that we give too much credence to our abstractions. We shorten the distance between our judgment of a thing and what that thing “is” until they are one of the same. What the world “is”, is comprised of our accepting a map as easily as we hear an uttered judgement, in the time of its hanging in the air, only as long as it takes to be spoken. The structure of a map may or may not be like the land, but a structure of a map is something that we know. We read it, and we know that it symbolizes space that is habitable. When this maps fails, we are not lost— we just don’t know where we are.

The third map, manifested famously in a particular instance by technology, was actually two maps— or the difference between two maps. When iPhone users updated their devices to a new version of the operating system in September 2012, they discovered that not only had Apple replaced the Google Maps program with a new Apple Maps program, but there were serious usability discrepancies between the two. Turn-by-turn driving directions had been added, but public transit directions had been removed. Search functions were lacking in the brand-new Apple Maps, as the hard work done by Google Maps to verify place data was no longer accessible. And the Street View data, meticulously collected by Google employees with 360-degree cameras on the ground for years, was replaced by an aerial “3D” view feature, that left odd glitches in the data: for example, portraying underpasses as solid walls, and making bridges over water appear melted.

![]()

The switch of map platforms, a decision made on the corporate level, betrayed what each of these platforms really were— a complicated stitching together of massive amounts of descriptive data, GPS information, and aerial photographs. Each of these two maps was actually millions, if not billions of maps. What allowed the map to be perceived as singular, and to make it useful as a means for orienting oneself in real space using a mobile device, was the seamlessness of the platform’s presentation of very similar data. The data— the maps themselves— were not dissimilar from each other. But the skip between one program’s presentation of the map data and the other’s, as it was presented for human reading, made all the difference.

The Apple Map “problem” is hardwired into our human capacity for navigation. Even if Apple had the time and resources to replace Google Maps with a program that was seamless and indistinguishable, this problem would have resulted at some point. It has before, and it will again. It could be a crash in the server, a forced downgrade to a phone without GPS maps, or any other real world issue that would separate us from seamlessly absorbing that useful abstraction of the map. We know that our sense of time-space is internal to our brains, and we know that the map is not the territory. But we don’t realize that our ability to use a map is because of the seamless integration of thousands of previously observed maps, of preconscious data visualizations in our perception and mind, of mental schema, and of their historical entanglement. Until, the occurrence of the glitch. Then we see the scaffolding of schema that underlies our perceptions. When this map fails, we are not necessarily lost, and not necessarily unaware of our location. At this point of failure we are conscious of how much of the world we know is only a map.

The Future-Present archetype we are encountering is not GPS, not our neurology, nor the ability of us to understand and make maps. It is the map that necessarily comes apart in our hands. It is the somewhat disconcerting revelation that the schema we use to understand history and our place in it, are it. To feel lost is a crisis of our person, and to have one’s recorded position displaced is a crisis of data. But to have the concept of a map devolve, is not so much a crisis of history, but its most visible presence. We have folded the Future-Present so deeply into our perceptions of the world, that sometimes we see it best when we fail to see it, when the overlapping schema we have stitched into our conception of everything becomes unthreaded, and we can look into the seams. In between the frames? Only more seams behind it. Seams, as it is said, all the way down.

Augmented reality presents opportunities to both extend and collapse the sense of self across spacetime. There is a deep revelation in this technology that promises to show us the hidden attributes of the world around us. It can be confronted as an occult technology in that it simultaneously reveals the hidden and offers a hidden view. What we see through AR can reinforce our personal experience of the world - what I see may become radically different from what you see - while simultaneously allowing us to share access to a common dataset underlying physicality - what I see contains the same rich detail as what you see. In this there is a path of algorithmic containment just as we see in all current algorithmic content streams, reinforcing what you like and filtering out what you don't. This is something that celebrates our individuality while robbing us of the agency to grow and see differently. If our adaptation requires seeing problems in new ways, will algorithms dull or enhance this ability?

- Chris Arkenberg

If we invented a technology that broke our mental schema for good, would we realize it in time? We map the levees around our cities, to be prepared for their inevitable ruin and failure. But what of the failure of the levees on the maps themselves? What of the failure of the levees in our conscious thoughts? These berms may not erode nearly as quickly, but that is not to say their are impermeable. Consciousness has always been too big to fail, but that is no guarantee.

The fans of [Future-Present] tech are indeed cross-disciplinary in their vocations. It may be more useful to look at the personality traits that incline a person towards such interests. They are hardware folks fascinated by the mechanics of functionality, the specs & schematics, the operational capabilities and engineering tolerances. They are military buffs into the tools of power & survival, the nuances of geopolitics, and the flow of milspec into civilian space. They are tech geeks looking for signs of their scifi fantasies coming to life; activists guarding civil liberties and revealing corruption; cybernetic psychologists tracking the ingression of the algorithm into the body; coolhunters & trendwatchers, analysts & futurists fed by the Edge, always propelled towards the precipitous drop into tomorrow. These types of orientations often emerge in childhood, reinforced by formative experiences and natural abilities. But as expressions of imagination, objects of novelty, and tools of functionality, technologies - especially the radical ones - always captivate our attention.

There may also be deep evolutionary structures compelling us to pay attention. Maybe something within our psyche is projecting into our technologies and demanding that we keep pushing forward, to the West, out to space, into the inner unknown. We are planners, after all, always watching the horizon to be prepared for tomorrow.

- Chris Arkenberg

It is good that we have so many people paying attention. The deep evolutionary structures that Chris suggests might be our only hope for survival. Our schema may be doomed to shatter, but saving grace is that we seem innately driven to construct replacements. The schematic opportunities in the Future-Present may be few or many, but considering these things from a variety of relative perspectives should hopefully keep us from fatally surprising ourselves.

[Identifying the Future-Present is] a framing thing. We have subconscious biases about who should be doing what. I’ve had male friends watching their kids on the playground— and people come up and ask “where’s the mom?” because no one assumes that the father would be with the kids on the playground. These are subconscious schemas about who should be doing what. It’s rarely malicious, it’s just part of our culture. It’s like taking the red pill in the Matrix. Once you learn about gender schemas, you totally see it everywhere. Sadly, there’s no going back. It’s not an unqualified win.

It’s not a totally design-based thing; it’s about the way we learn. If you have a schema or a mental model of what a used car salesman looks like and how they behave, it’s useful. If you think the person you’re buying the car from has your best interests in heart, that’s not good. The idea of framing, that once things are pointed out to you it’s possible to see them as part of a larger whole, is part of a broader psychology. “Culture is all the things you do that you don’t know why you do them”... I don’t know who said that originally. I didn’t realize I was Canadian until I moved to the US. I apologize to people when I bump into them, even if it is totally their fault. That was a thing I did without thinking until I was in a place where that did not happen, and then I became aware of it. That’s the nature of culture.

- Deb Chachra

![]()

It is a chicken-and-egg question to ask if we develop schema-altering technologies by accident and then react to them, or whether we create technologies that purposefully incite new schemas as a way to seek new perspectives. It’s been suggested, in the conversation surrounding Venkat Rao’s “Manufactured Normalcy Field”, that our development of technology is done in such a way as to seek novelty, or alternatively, seek as little novelty as possible. Perhaps neither is truly the case. Technology doesn’t want anything that approaches the meta-schematic level of “novelty”, nor do human beings. Our desires don’t function on the semantic level of mapped culture theory. We don’t seek novelty, it is with the schema of “novelty” that we are able to describe what we have produced. Like Deb suggests, it is not whether or not the human schematic response to an instruction or a piece of technology is perfectly correct, or of a particular discourse. The framing we give a thing is the ultimate significance of that thing, for better or worse. But it is not that thing. Our experience of consciousness is a cataloging of shadows.

I feel optimistically that there is a sort of archive impulse. There are people who like going to libraries and taking out books. But people also make photo albums, collect cookbooks, etc. People like to form multimedia databases. There’s a connection to memory through objects and other media artifacts. This wouldn’t get you into an Ivy League school or even get you an A in a class. But there is an archive fever. People like setting up a system and fitting things into it. Even through Facebook, people are engaged through this sort of activity. With the internet--just like the release of the Kinsey report--suddenly we realize, “my God, everyone’s doing it.” It’s allowing more people to engage in these conversations, and it’s revealed that all along people were into this. They just didn’t live next to an academic library.

I don’t know if this means that this is making more people like that, or just revealing them. But it is definitely allowing people to do things that they had been wanting to do all along. There are people with incredibly detailed photo albums. It’s the same impulse, to organize info, brought into the mainstream.

- Geoff Manaugh

Art may serve as a strategic reserve of schematization. Rather than simply mapping the quickest route from point A to B, we have people who hide data in brick walls, or embed codes in the ambient surface patterns of nearly any object. The shortest distance is a line that can be cut, but the wider net of meaning in a space can survive a blockage in the flow. Schematically, art complicates rather than simplifies. Not everyone is economizing and minimizing. Others are obscuring, obfuscating, and accentuating until the basic becomes the baroque. The same impulse that drives us to aesthetically tile the world’s into 3D maps also causes us to add apopheniac tags to the world, making some sort of pattern— or better yet, making so many opportunities for new patterns that the patterns begin to fade into noise.

There's no danger that people are actually and literally going to make everything they can dream up. There's been something of a lowering of the barriers to aping Thomas Edison and tinkering in an industrial lab, but there are still plenty of genuine barriers, and they'll weed out the people who are delusional about their maker chops. It's quite hard to make effective things, especially without some hard-won understanding of the tools and the grain of the material.

The Makers scene is like what happened in publishing, in music, and in video, but it's for objects. There's a lot of semi-effortless music and video around nowadays, too, but if you think you're gonna compose like Wagner and film like Fellini, well, you won't.

—Bruce Sterling

The truth of society’s open schematization of the world is that there are no standards, no rules, and no moderating authority. There is no grand design, and no underlying pattern to be discovered, other than the patterns themselves. Schematization can bring amazing things to light, bury important things deep, and dissolve away into its component pieces in seconds. We are left standing in the middle of this map, watching one edge crumble away while we draft and paste additions onto the other, wondering what will happen to the area seemingly supporting our weight.

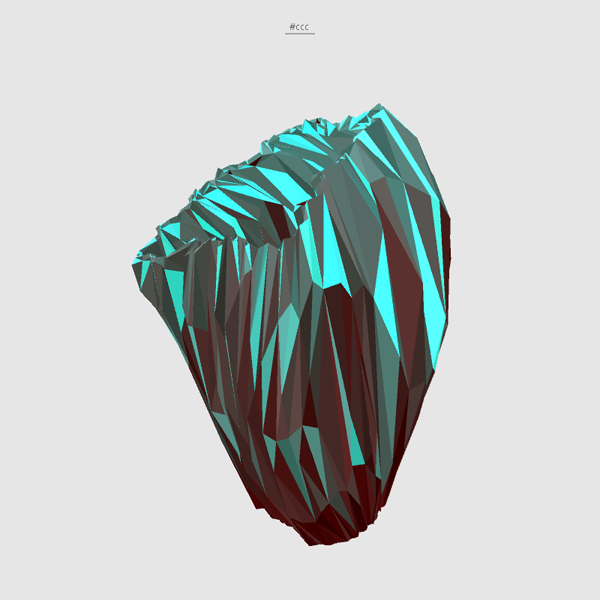

Previously:

Rocks (mirrored)

Rocks (mirrored)